Abstract

Some fundamental concepts of catalysis are not fully explained but are of paramount importance for the development of improved catalysts. An example is the concept of structure insensitive reactions, where surface-normalized activity does not change with catalyst metal particle size. Here we explore this concept and its relation to surface reconstruction on a set of silica-supported Ni metal nanoparticles (mean particle sizes 1–6 nm) by spectroscopically discerning a structure sensitive (CO2 hydrogenation) from a structure insensitive (ethene hydrogenation) reaction. Using state-of-the-art techniques, inter alia in-situ STEM, and quick-X-ray absorption spectroscopy with sub-second time resolution, we have observed particle-size-dependent effects like restructuring which increases with increasing particle size, and faster restructuring for larger particle sizes during ethene hydrogenation while for CO2 no such restructuring effects were observed. Furthermore, a degree of restructuring is irreversible, and we also show that the rate of carbon diffusion on, and into nanoparticles increases with particle size. We finally show that these particle size-dependent effects induced by ethene hydrogenation, can make a structure sensitive reaction (CO2 hydrogenation), structure insensitive. We thus postulate that structure insensitive reactions are actually apparently structure insensitive, which changes our fundamental understanding of the empirical observation of structure insensitivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Supported metal nanoparticles are a highly important class of heterogeneous catalysts, used for a range of applications: from food preparation to bulk and specialty chemical synthesis as well as emissions control. Studying nanoparticular systems under catalytic reaction conditions is far from trivial, spectroscopic signals are generally very low, for surface sensitive spectroscopies, and bulk techniques. Firstly so, because the fraction of exposed surface on a nanoparticle is low1,2. Of that small fraction of surface, an even smaller fraction is active. There is generally a low signal-to-noise ratio3. Secondly, the variety of adsorption sites is large and ill-defined, and there are multiple surface elementary processes happening in tandem. There are broad and convoluted spectroscopic signals4,5,6. Thirdly, relevant surface processes consist of several consecutive elementary reaction steps. The adsorbate-surface systems change dynamically7,8, which is system-inherent and thus desirable to study. Experimentally this is highly challenging, particularly so considering reasons 1 and 2 listed above. As such, an overwhelming majority of studies in literature have simplified the systems under study for example by using single crystal facets, studied under ultra-high vacuum conditions (an approach that is termed surface science)8,9,10,11,12,13. These approaches have yielded many of the important insights that we currently build our understanding on. However, in recent years it has also become apparent that adsorbates and surfaces have completely different physical parameters, such as surface stability, mobility of species, surface coverages, and surface energies, at relevant conditions of pressure and temperature12,14,15.

Structure (in)sensitivity is a fundamental physical concept in catalysis, which relates the rate of a catalytic reaction per unit surface area to the size of a nanoparticle16. If this rate per unit surface area changes with catalyst particle size, a reaction is termed structure sensitive. Conversely if it does not—a reaction is termed structure insensitive. For structure sensitivity, surface science studies have unequivocally shown that in order for the cleavage or formation of certain bonds to proceed efficiently, some specific groupings of surface atoms are required17,18,19,20,21. The population of these surface sites varies with nanoparticle size. It is commonly accepted to classify reactions as being either of two types of structure-sensitive, or to be structure-insensitive depending on whether, and how the surface-specific rate (or turnover frequency, TOF) is a function of particle size. Structure insensitive reactions empirically show no - or very little- dependence of reaction rate on particle size. A typical example is the hydrogenation of alkenes20. Despite the fact that not many heterogeneous catalytic reactions have been studied more intensively than olefin hydrogenation22,23,24, these classic examples of structure insensitive reactions are still not entirely understood. It has been noted8,16,21 that it is surprising that the rate of any reaction should be insensitive to the different sites exposed on different sizes of nanoparticles. Different explanations have been given for the observed effects, from carbonaceous overlayers25, to a very strong structural dependence on a specific surface site21 (it must be noted that this explanation obviously only holds for single crystal facets in surface science), to surface restructuring8. All of these explanations stem from surface science studies (though restructuring has been shown to occur under reaction conditions26,27), yet single crystal facets studied under vacuum conditions are in stark contrast to the supported nanoparticles in practical catalyst materials, which are structurally much more dynamic, and inhomogeneous. To enhance our fundamental understanding of such principles as structure sensitivity on working catalysts, it is of the essence to develop and apply time-resolved analytical techniques12,28 to simultaneously monitor the dynamic changes that occur on both sides of chemical bond formation on the surface of a solid catalyst: the adsorbate (often organic) and the substrate (often inorganic).

Here we study how the size of metal catalyst particles affects dynamic surface changes during structure sensitive, and “structure insensitive” catalysis with operando millisecond quick-X-ray absorption spectroscopy (quick-XAS), operando Fourier Transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) both with on-line product analysis via an ultra-fast GC, and in-situ high resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM). A deeper understanding of such fundamental concepts in the interface chemistry of nanoparticles under working conditions can ultimately help us to rationally influence reaction rates by intelligent control of active sites.

Results and discussion

Counterintuitive X-ray absorption spectroscopy results

It is clear that much is still not understood with respect to the concept of structure insensitivity in catalysis. To this end, here we will examine the nature of the behavior of a set of SiO2-supported Ni nanoparticular catalysts with mean particle sizes ranging from 1–6 nm, under working conditions. The catalysts are compared in a classically structure sensitive reaction (CO2 hydrogenation), and structure insensitive (ethene hydrogenation) reaction with state-of-the-art operando spectroscopies in an attempt to understand dynamic changes onset by catalysis on nanoparticles. Three powerful characterization techniques are used to this end, two bulk techniques; operando Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, operando quick-X-ray absorption spectroscopy, and a single particle technique; in-situ high resolution transmission electron microscopy.

The catalysts with different mean particle sizes were first employed in catalytic testing in these reactions to verify their respective structure (in)sensitivity. Figure 1a, b show the particle size dependent TOFs plotted on a linear scale. Thereby we can deduce that for CO2 hydrogenation the activity shows a significant change with particle size (showing both new data, and data from a previous publication29), while for ethene hydrogenation such a change in activity is much less apparent. Supplementary Note 1 of the Supporting information alludes to the full catalytic details of these reactions, including an extensive literature review on structure sensitive versus reactions that are apparently structure insensitive, which ends by comparing our catalytic results to the available literature on the structure (in)sensitivity of these reactions. Supplementary Methods in the Supporting information gives additional information on the applied materials and methods.

a, b Structure sensitivity versus structure insensitivity plotted on a linear Y-axis. The influence of the Ni mean particle size on TOF for a CO2 hydrogenation at 300 °C and b ethene hydrogenation at 150 °C. The Supplementary Information S1 shows alternative plots, and an extensive literature search on both structure sensitive, and insensitive reactions. c, d Operando FT-IR spectra during CO2 hydrogenation at 300 °C and ethene hydrogenation at 150 °C, respectively for three different mean particle sizes of Ni/SiO2. X-ray absorption spectra (XAS) with 2 s time resolution obtained upon switching from pure H2 after reduction, to either CO2 (e) or ethene (f) hydrogenation. g, h absolute magnitude of change induced by the onset of catalysis (seen in e, f) at the Ni K-edge using the largest Δ, at 8333 eV and the second largest Δ at 8370 eV indicated by the dotted lines in (e, f) and normalized for available surface area, for CO2 (g) and ethene (h) hydrogenation.

Figure 1 shows operando spectroscopic (FT-IR, and XAS) data for the structure sensitive CO2 hydrogenation, and the “structure insensitive” ethene hydrogenation reactions. The vibrational frequencies in the IR spectra for the reaction intermediates of structure sensitive CO2 hydrogenation differ greatly with different mean Ni particle size (Fig. 1c). Most notable is the region for top- and bridge-adsorbed CO (2060–1900 cm−1), and in the formate region (~1590 cm−1). This has been noted before and has been found to explain the structure sensitivity of this reaction, as an optimal binding strength of CO is required29. On the other hand, for the structure insensitive ethene hydrogenation (Fig. 1d) the vibrational frequencies in the IR spectra for different particle sizes show no differences for different particle sizes. The main species that are detected for ethene hydrogenation (H2:ethene 1:1) are CH3 stretch vibrations of gaseous ethane at 2980 cm−1 and CH2 stretch vibrations of chemisorbed ethene at 2893 cm−1 (refs. 30,31,32). Supplementary Fig. 14 shows that at high ratios of H2:ethene, different intermediates are in fact detectable (for example the C-H stretch from methane at 3015 cm−1)33. Thus, the different mean Ni particle sizes in Fig. 1b truly share very similar intermediates during ethene hydrogenation.

While FT-IR is a powerful vibrational spectroscopic tool to detect organic species, reactants, products and intermediates of heterogeneous catalytic reactions, operando hard X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS, Fig. 1e, f), is a powerful tool to study the inorganic aspects of a catalyst. For example, changes in the local electronic structure which could appear through the introduction of adsorbates or by the onset of a catalytic reaction (the ‘Supplementary Methods’ section, and ‘Supplementary Discussion – X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy’, more specifically Supplementary Figs. 15–S22 give additional details on our XAS measurements). The local electronic structure of Ni is probed in this case by measuring the K-edge at 8333 eV. When XAS spectra are normalized, a change in the features of the X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) indicates a quantifiable change in electronic structure and/or geometry of our Ni catalyst nanoparticles. In Fig. 1e, f, operando XANES spectra are shown for 3 samples with differing mean Ni particle sizes, recorded during a switch from H2 to catalysis - ethene, or CO2 hydrogenation (1:1 ethene:H2, 1:4 CO2:H2).

Interestingly, when comparing the XANES spectra for CO2 hydrogenation (Fig. 1e) and ethene hydrogenation (Fig. 1f), there is a clear difference comparing the two reactions. This is for example seen by the shift in energy of the features around 8390 and 8415 eV, indicating that the local electronic change that is induced by ethene hydrogenation (the structure insensitive reaction) is much larger than the electronic change onset by CO2 hydrogenation (the structure sensitive reaction). Hence, while FT-IR aligns well with expectations based on activity for the structure sensitive and insensitive reactions (Fig. 1a, b), the corresponding changes observed with XAS seem counterintuitive at first glance. Cargnello et al. recently showed that the correlation of certain particle size parameters with activity trends is an excellent way to determine the cause of activity trends34. Along this line of thought, the fact that these two parameters do not align requires further investigation.

Figure 1g, h shows the two largest absolute changes in X-ray absorption (identified at X-ray energies 8333 and 8370 eV, indicated in Fig. 1e, f by dotted gray lines). These figures show in a more quantitative way that the changes in the XANES are larger for ethene hydrogenation than for CO2 hydrogenation. These values were normalized to the exposed surface area. If one compares the overall magnitude of changes onset by CO2 hydrogenation, versus those that are onset by ethene hydrogenation, it is clear that in the latter case more restructuring occurs for all particle sizes. Interestingly, the particle size dependence of the restructuring shows that the most active mean particle size for CO2 hydrogenation also restructures the most (Fig. 1a, g). For ethene hydrogenation, the degree of restructuring increases with increasing Ni NPs size (Fig. 1h). Interestingly, larger Ni particles are perturbed much more than smaller ones even after normalization to the amount of exposed surface. It is remarkable to see that the degree of restructuring for ethene hydrogenation is highly particle size dependent but the TOF (Fig. 1b) is not.

Sub-second EXAFS reveals size-dependent restructuring trends

By studying the dynamic nature of the perturbation of the metal nanoparticles under catalytic conditions, we can obtain additional insight into the interesting observation that the structure insensitive reaction shows particle-size dependent restructuring. To the best of our knowledge, no such experimental study has been done on the particle size dependent nature of restructuring in catalysis35. To obtain time resolved information, we measured quick-X-ray absorption spectra with 100 ms time resolution (before binning) during alternating pulses of CO2 or ethene, alternated by pure hydrogen (see Supplementary Information section ‘Supplementary Methods’, and Supplementary Figs. 15–22). Similar trends were observed for catalytic conditions (that is, pulses of H2 alternated with H2 + reactant, Supplementary Fig. 21). All the spectra were recorded while measuring the products by gas chromatography (GC) with <10 s time resolution to ensure working catalytic conditions (see also Supplementary Fig. 22). The Fourier-transformed extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) for the CO2 experiment alongside the ethene experiment are plotted in Fig. 2, binned to 2 s time resolution to increase the signal to noise ratio. The spectra are plotted sequentially in time on the Y-axis, with the intensity expressed by the color scale (see also Supplementary Figs. 24–29, and in particular Supplementary Fig. 29 for the average EXAFS of each experiment shown in Fig. 2a–f).

Top view of the Fourier transform of the quick-XAS spectra at 2 s time resolution of feedstock pulsed experiments for 3 catalyst samples with different mean Ni particle sizes. See also relevant EXAFS in the Supporting information, Supplementary Figs. 15 and 28. a, c, e pulsing CO2 and H2 at 400 °C and b, d, f pulsing ethene and H2 at 150 °C and ambient pressure. See Supplementary Fig. 29 for the average EXAFS of each experiment shown in a–f.

Notably, the Ni-Ni peak at approximately 2 Å (uncorrected for the photoelectron phase shift) increases systematically during ethene pulses by approximately 0.05 Å (e.g., in Fig. 2f), while no such periodic changes are observed for CO2 pulses. This observation indicates that the average Ni-Ni bond expands under ethene and, subsequently, contracts under H2. A second remarkable feature, visible in Fig. 2d and again most notably in Fig. 2f, is that the degree of local disorder in the catalyst sample changes reversibly during pulses of ethene and H2. This can be seen by the (dis)appearance of Ni-Ni multiple scattering paths at around 4 Å, which decrease (under ethene) and increase (under hydrogen) in intensity with a constant, and low noise level. Furthermore, a shoulder appears at 1.50 Å, in concert with the disordering of the particle. This can more clearly be seen in Supplementary Fig. 15. On the basis of the visual observation of these EXAFS data in Fig. 2 we can hypothesize that increased Ni-Ni bond length disorder is caused by the intercalation of carbon through the surface layers of Ni nanoparticles. Most interestingly, a particle-size dependent degree of reversibility of these structural changes35, correlating with ethene pulses, can also be seen in Fig. 2f. The reversibility of this expansion and contraction, or “breathing”, is particle size-dependent as can be seen in Fig. 2d where for the 2.1 nm catalyst sample that is shown, this “breathing” appears to halt after a few pulses, while it is not visible for the smallest particle size.

We can finally confirm this qualitative picture by quantitative EXAFS data analysis, as described in detail below (see also section ‘Supplementary Discussion – X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy’ in the Supporting information). By using the fits (FEFF6) of the time-resolved EXAFS data, we determined the variation of σ2 (the mean-square relative displacement, MSRD) in the EXAFS equation, which can be interpreted as a measure of distortion for a sample at a given temperature. Because the temperature was constant as measured by a thermocouple inserted in the catalyst bed (and repetitions at lower temperatures yield similar trends, see Supplementary Fig. 20) we conclude that the nature of the variation in MSRD is configurational, and not due to vibrational disorder. If caused by the diffusion of carbon through the outer layers of Ni nanoparticles, the time-derivative of the MSRD data should be comparable - by dimensionality argument at least - to the diffusion coefficient of carbon in nickel as we discuss in more detail below.

Supplementary Fig. 26 shows σ2 plotted against time on stream. Figure 3a, b show the derivative (\(d{\sigma }^{2}/{dt}\)) plotted against time on stream during the pulsing experiments of CO2 and ethene, respectively, which are shown in Fig. 2. As emphasized above, due to the isothermal conditions of the gas switching experiments, the behavior of the derivative over time of σ2 as plotted in Fig. 3a, b should be interpreted as primarily caused by restructuring that is, evidently, adsorbate-induced. Thus, with the extraction of Δtσ2 from the time-resolved quick-XAS data, we now have a parameter displaying the magnitude of restructuring of the particle, which allows us to deduce kinetic information of this observed restructuring for the catalyst samples with differing mean Ni nanoparticle size. This is highly interesting, because we observed that the structure insensitive reaction restructures supported metal nanoparticle catalysts particle size-dependently.

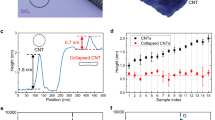

a, b Batch analysis of CO2- and ethene-pulsed modulated excitation experiments shown in Fig. 2. For each particle size, 50.000–70.000 spectra were individually fit, fixing the coordination number but varying σ2. The values have been given an arbitrary offset for clarity. c The diffusion coefficient of C as calculated from time-resolved XAS measurements, plotted with the ethane TOF and the ratio of methane/ethane for 3 catalyst samples with different mean Ni particle sizes. d, e The turnover frequency (TOF) of ethene converted to methane (d) and ethane (e) per surface nickel atom per second, measured at 150 °C 1:1 H2:ethene with a GHSV of 2.000. f, g, h In-situ BF-STEM images of nanoparticles deposited directly onto SiN membrane via spark ablation, in gaseous environment of f H2 at 150 °C, g ethene at 150 °C, h and H2 at 150 °C.

Figure 3b shows Δtσ2 for structure insensitive ethene hydrogenation, from which we can note some very interesting trends. Firstly, Fig. 3b shows that the reversibility of ethene-mediated restructuring decreases with decreasing catalyst particle size. That is, the sample with larger mean Ni particle size shows changes of features in time that continue to correspond to the applied external gas throughout the experiment, but for the smaller mean particle sizes this same trend fades out. The X-ray absorption spectra of these samples have nominally the same signal to noise ratio (see for example Supplementary Fig. 17). Secondly, we see that there is always a degree of restructuring that seems to be irreversible (in the beginning the change is always largest). The third observation is that larger particles have a more significant slope for ethene-induced restructuring, and hence restructure faster, than smaller particles do. As the variation of Δtσ2 is derived from the EXAFS shown e.g., in Figs. 1 and 2, the integral of the rate of restructuring, can be related to the overall magnitude of restructuring to ensure we did not miss, for example, very fast restructuring in the small nanoparticles which does not seem to be the case. Our observation that larger particles restructure faster than small ones is unexpected, as the more open, or stepped surfaces (i.e., smaller nanoparticles) are thought to be the less rigid36. Indirect observations in literature have also pointed towards smaller particles spontaneously restructuring faster37. It is interesting to note, however, that carbon diffusion in Ni was reported to be highly anisotropic due to the difference in energy barrier for migration parallel to grain boundary (Ea = 42–74 kJ mol−1) versus lattice diffusion (Ea = 160 kJ mol−1)38. Such a difference in activation energy at 150 °C results in approximately 1010 times faster kinetics, such that C migration along grain boundaries may happen in the order of the seconds that we record. We therefore argue that the larger Δtσ2 change observed for the larger nanoparticles could be explained by C diffusion in the bigger nanoparticles along grain boundaries, which were observed by HRTEM (see Supplementary Fig. 31).

The speed of carbon intercalation in nanoparticles

In fact, the time resolved distortion of the nanoparticle structure induced by ethene hydrogenation, can yield insight into the intercalation of C species into our metal nanoparticles, which seems to occur particle size-dependently for this structure insensitive reaction. The perturbation of our nanoparticles by C can be qualitatively compared (by the dimensionality arguments) to the diffusion coefficient of carbon in Ni. This, in turn, can be evaluated via the Einstein diffusion equation (see Supplementary Note 4). In fact, the derivative of the mean-square relative displacement (MSRD) σ2 over time (Fig. 4a, b, and Supplementary Figs. 18–20), can be related, by dimensionality, to the diffusion coefficient of C in Ni. A deeper look into this process helps extend the connection between the species and processes involved in the carbon-induced perturbation of our nanoparticles. Evidently, two processes take place in Fig. 3b. One sharp peak, a fast, physical process (i.e., relatively low Ea barrier) with the onset of an ethene pulse, and one less sharp slope (i.e., relatively high Ea barrier), during the same ethene pulse. By taking the maximum of the first peak for each nanoparticle size in Fig. 3b and comparing the found values to literature, we find firstly that the carbon diffusion coefficients are in the same order of magnitude as one would expect based on the equation of Lander et al. (with an average of 3.5 × 10−21)39, and secondly that the calculated carbon diffusion coefficient increases with mean Ni particle size. That is, the larger the particle, the faster C apparently diffuses for ethene hydrogenation experiments. Considering the match in C diffusion from the experiments and literature, and knowing that the respective activation energy barriers for C diffusion are in the range of 120–150 kJ/mol39 (as with the diffusivity, activation energy barriers can be calculated), we rationalize that the other slower physical process must have a larger Ea as activation energy barriers are directly related to rate of occurrence. Such a slower process, for example, could be the deformation of particle shape or the removal or positional distortion of atoms from a surface facet. For Ni, these occurrences could be on the order of 150–428 kJ/mol, calculated by taking the cohesive energy of Ni divided by 12 (bulk), multiplied by a number of different adatom formation possibilities15. Hence, we can say that the surfaces of our catalytic nanoparticles are likely distorted by examining the perturbations observed by XAS.

a Turnover frequency of CO2 hydrogenation over two Ni catalyst samples with differing particle size, before and after surface modification with ethene. b FT-IR spectra of Ni sample with 1.2 nm mean Ni particle size in CO2 hydrogenation before and after surface modification with ethene. c, d DRIFTS phase domain spectra of CO2 modulation excitation experiment c before and d after surface modification with ethene.

To prove that this is the case, one may deduce the volume fraction of C that is intercalated into the metal nanoparticles, from the time resolved quick-XAS experiments, and different particle sizes, and the respective disorder factors. The calculated diffusion values indicate that, in a time in the order of 10 s (in which we observe the variation of \({\sigma }^{2}\)), the nuclear mean square displacement of C is in the order of 1 × 10 Å−2, and since this is much smaller than a Ni-Ni distance (2.5 Å) carbon should only occupy surface sites in our case. Nonetheless, as Supplementary Fig. 26 shows, the 1.2 nm NPs have the smallest change in the \({\sigma }^{2}\) values, and the 4.4 nm the greatest, with a ratio of

This is unexpected since the ratio of the surface sites in 1.2 nm and 4.4 nm nanoparticles is

indicating that either the surface of the smaller nanoparticles is not entirely restructured or that the bigger nanoparticles are restructuring also (partially) in their bulk. See also Supplementary Note 5 for more details on this calculation. An excellent way to check if these are carbidic-type (defined here as C adatoms – not necessarily an ordered periodic carbide structure) or C2 reaction intermediates that are restructuring the surface, is to check the formation of odd-Cx-numbered oligomers in our GC data. If we examine the product distribution of our Ni catalysts with different particle sizes in ethene hydrogenation, we can see that every catalyst (see Fig. 3c–e) converts a small amount of ethene to methane, implying that there is at any given point in time also molecular carbon (i.e., carbidic), or CHx fragments, on the surface.

The more significant restructuring for larger particles thus likely reflects more bulk carbide formation. The fact that we see product formation at similar turnover frequencies for the operando quick-XAS experiments (see Fig. 3c–e, and Supplementary Fig. 22) as reported in literature23 and our experiments in Fig. 1, indicates that our catalyst is not simply poisoned by these carbon fractions. It is important to note that as such, these C-induced perturbations (whether they be on the surface or in the bulk of the nanoparticle), do not poison catalyst activity.

In-situ STEM corroborates at the single-particle level

The results that have been discussed up until now all consider bulk measurements (FT-IR, quick-XAS). To assess whether similar results could be found at the single nanoparticle level, in-situ high resolution scanning transmission electron microscopy (HR-STEM) measurements were performed. Section ‘Supplementary Methods’ of the Supporting information lists details on sample preparation and experimental procedures. Figure 3f–h (and Supplementary Figs. 29–33) shows in-situ HR-STEM results of Ni nanoparticles directly deposited onto SiN membranes via spark ablation of Ni electrodes (see ‘Supplementary Methods’ section on spark ablation). The average lattice spacing of the Ni nanoparticles was measured directly on several nanoparticles using Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) in H2, subsequently in flow of ethene, and once more in H2 (see Supplementary Figs. 29–33). Upon the introduction of ethene, an average surface expansion of +1.7 ± 0.9% was measured (over ~4.5 nm2 in 5 separate particles each existing of at least approximately 8.000 Ni atoms based on the nanoparticle size in nm14) while the subsequent contraction upon the introduction of hydrogen was −1.6 ± 0.9%. Therefore, indeed, also some intercalation of carbon must occur under ethene environment as STEM is not a surface sensitive technique.

In light of the fact that both the bulk and single particle levels showed lattice expansion upon the introduction of ethene hydrogenation, it is now interesting to discuss whether we can relate these observed dynamic surface perturbations to structure insensitivity. Regardless of the interesting question about what exact type of strongly bound C is restructuring the Ni surface so significantly, it is clear that the impact of these species is different for different catalyst particle sizes (e.g. Figs. 1h and 3b). Somorjai and coworkers determined that an ethylidyne intermediate (C2H3) is very strongly bound to the surface via a threefold carbon metal bond under specific reaction conditions40. This specific strong adsorption can create trenches in which a row of surface atoms is exposed over which π-bonded ethene (the proposed active intermediate in ethene hydrogenation) reacts8,41,42. Imagining such a type of carbon species adsorbing on the surface could thus mean that a predetermined fraction of sites may be exposed no matter what the previously exposed surface consists of. For ethene hydrogenation, upon the ethylidyne-induced creation of these trenches, a surface expansion of approximately 1.5%–2% is expected36.

Apparent structure insensitivity

The experiments we show here clearly imply that the structure insensitive heterogeneous catalytic reaction ethene hydrogenation restructures different mean Ni nanoparticle sizes significantly but also particle size dependently. If there is still surface exposed after this ethene restructuring, and these exposed sites are of a specific site composition, then this can cause the observed structure insensitivity. To check these parameters, we performed a probe reaction with the goal to examine the effect of restructuring induced by ethene hydrogenation on a subsequent catalytic reaction, CO2 hydrogenation. Figure 4a shows the surface-normalized activity of 2 different Ni nanoparticle sizes in CO2 hydrogenation. Before surface modification by ethene, as plotted in Fig. 4a in pink, the two different particle sizes show significantly distinct particle size dependent activity, previously shown to be caused by the availability of different sites with different activity on these same catalytic samples29. The same catalyst samples were then exposed to ethene hydrogenation and subsequent hydrogenation of the catalyst surface, after which only irreversibly adsorbed C should be adsorbed on the surface (Fig. 3b). After this, CO2 hydrogenation was performed once more on the catalyst nanoparticles. The surface-normalized activity decreased significantly after this ethene-perturbation and was nearly indistinguishable for the two types of nanoparticles as can be seen in Fig. 4a. In other words, our previously structure sensitive reaction had become structure insensitive, while still being catalytically active.

Figure 4b–d show FT-IR spectroscopy experiments on the effect of this surface modification with ethene. Figure 4b–d demonstrate that CO2 activation does still occur, and that COads species are formed and consumed on the surface upon pulses of CO2. If there is still activity, and we still see CO-Ni vibrations (as we do), some sites are apparently left free by surface modification. This suggests that the restructuring onset by ethene is a structure sensitive occurrence—and the observed changes in activity are not just a poisoning effect. The ethene-onset restructuring exposes a certain fraction of sites which, apparently, make CO2 hydrogenation structure insensitive (Fig. 4a).

In light of these considerations, it is interesting to note that the most likely explanation for empirically observed structure insensitivity is not the absence of sensitivity to geometrical and electronic effects as generally assumed. We do wish to point out that even if ethylidyne, or any other surface carbon is the actual active intermediate in ethene hydrogenation, this reaction is “structure insensitive” for the trivial reason that the reaction does not proceed on the exposed metal sites and also in this case, structure insensitivity (that is, the absence of electronic and geometrical effects on a catalytic reaction) as often currently described in literature does indeed not exist. Rather, if structure insensitivity is empirically observed, it is caused by a surface that cannot simply be considered as the superposition of contributions from individual crystal planes.

As far as we are aware, this is the first report of the direct observation of particle size-dependent restructuring which is shown to increase with particle size, and of faster restructuring of larger metal nanoparticles. The interesting notion that there is always a degree of restructuring which is irreversible, and the proofs provided for more and faster intercalation of carbon for larger nanoparticles have obvious implications for the catalytic reactions that follow on such metal nanoparticles particles. Although our findings are based on experiments with Ni nanoparticles supported on SiO2 and two specific catalytic reactions, we believe effects of similar nature are to be found (to larger or smaller extents) throughout reactions on supported metal particles and thus we believe these experiments also to be relevant to interface chemistry and related fields.

Methods

Catalyst synthesis

Silica supported Ni nanoparticles were made by homogeneous deposition precipitation (HDP), and coprecipitation according to e.g. Ermakova et al.43 or de Jong and Lok44,45. All catalysts (see Supplementary Information) were prepared by HDP except 6.0 nm Ni/SiO2. To this end different weight loadings (1–20%) of Ni precursor were brought in solutions along with suspended silica, and pH was increased under continuous stirring by addition of an alkaline solution. Sample 6.0 nm Ni/SiO2 was made by coprecipitation of NiCO3 with silica precursor in solution, precipitation was onset by addition of NaOH. The catalyst samples under investigation have varying Ni mean particle sizes, as listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Catalyst characterization

All details on catalyst characterization can be found elsewhere29.

Operando FT-IR with on-line product analysis

Operando Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy measurements were performed to study a structure sensitive reaction (CO2 hydrogenation) and a structure insensitive reaction (ethene hydrogenation) over SiO2 supported Ni catalysts with varying particle size. Product formation was followed by on-line gas chromatography. Before each reaction, catalysts were reduced (see also section ‘Supplementary Methods’ in the Supplementary Information. The overall procedure and setup has been described elsewhere29.

Operando quick-XAS with on-line product analysis

Pulsed operando X-ray absorption spectroscopy experiments were performed at the SuperXAS beamline (X10DA) at the Swiss Light Source in transmission mode. The X-ray beam from the 2.9 T bending magnet was collimated by a Si coated mirror and monochromatized with a Si(111) channel-cut crystal in the QuickXAS monochromator. The Si(111) crystal was rotated at a frequency of 10 Hz across the Ni K-edge, and the signals of the ionization chambers and the angular encoder were sampled at a frequency of 2 MHz. The edge energy for the Ni spectra was calibrated using a Ni foil. The measurements were performed in a custom-built operando reaction cell29. Q-XAS data was subsequently evaluated using the JAQ Analyzes QEXAFS version 3.3.53 software as well as self-developed Matlab™ code, preparing the data for batch fitting with Larch FEFFIT. Further information about the Q-XAS data processing can be found in the Supplementary information.

In-situ STEM

The in-situ STEM experiments were performed at the ORNL Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences using a Protochips Atmosphere in-situ gas cell system and a probe corrected FEI Titan S/TEM operating at 300 kV. Samples were prepared using the spark ablation technology of VSParticle, by use of their G1 nanoparticle generator (see section ‘Supplementary Methods’ of the Supporting information). The nanoparticles were directly deposited onto the SiN membrane of the Protochips MEMS reactors using the following parameters; 99.99% Ni, (Chempur), Argon 5.0 (Linde), voltage 1.3 kV, current 8.1 mA, flowrate 10 SLM, deposition time 6 min. The nanoparticles were heated under H2 and ethene gas to 150 °C at atmospheric pressure and imaged using bright-field (BF) and annular dark-field (ADF) STEM imaging.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The code generated to analyze the datasets during the current study are referenced, or available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Van Helden, P., Ciobica, I. M. & Coetzer, R. L. J. The size-dependent site composition of FCC cobalt nanocrystals. Catal. Today 261, 48–59 (2016).

Wulff, G. Zur frage der geschwindigkeit des wachsthums und der auflosung der krystallflachen. Z. fur Krist. und Mineral. 34, 449–530 (1901).

Taylor, H. S. A theory of the catalytic surface. Proc. R. Soc. A108, 105–111 (1925).

Filot, I. A. W. Quantum chemical and microkinetic modeling of the Fischer-Tropsch reaction. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. (2015).

Vogt, C. et al. Understanding carbon dioxide activation and carbon-carbon coupling over nickel. Nat. Commun. 10, 5330 (2019).

Maeda, N., Meemken, F., Hungerbühler, K. & Baiker, A. Spectroscopic detection of active species on catalytic surfaces: steady-state versus transient method. Chimia 66, 664–667 (2012).

Batteas, J., Dunphy, J., Somorjai, G. & Salmeron, M. Co-adsorbate induced reconstruction of a stepped Pt(111) surface by sulfur and CO: a novel surface restructuring mechanism observed by scanning tunneling microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 534–537 (1996).

Somorjai, G. A. The experimental evidence of the role of surface restructuring during catalytic reactions. Catal. Lett. 12, 17–34 (1992).

Wolff, J., Papathanasiou, A. G., Kevrekidis, I. G., Rotermund, H. H. & Ertl, G. Spatiotemporal addressing of surface activity. Science 294, 134–137 (2001).

Ertl, G. Reactions at surfaces: from atoms to complexity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 3524–3535 (2008).

Kleinle, G., Penka, V., Behm, R. J., Ertl, G. & Moritz, W. Structure determination of an adsorbate-induced multilayer reconstruction: (1x2)-H/Ni(110). Phys. Rev. Lett. 58, 148–151 (1987).

Somorjai, G. A. & McCrea, K. Roadmap for catalysis science in the 21st century: a personal view of building the future on past and present accomplishments. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 222, 3–18 (2001).

Somorjai, G. A., Contreras, A. M., Montano, M. & Rioux, R. M. Clusters, surfaces, and catalysis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 10577–10583 (2006).

Qian, J., An, Q., Fortunelli, A., Nielsen, R. J. & Goddard, W. A. Reaction mechanism and kinetics for ammonia synthesis on the Fe(111) surface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 6288–6297 (2018).

Eren, B. et al. Activation of Cu(111) surface by decomposition into nanoclusters driven by CO adsorption. Science 351, 475–478 (2016).

Letter S. in Catalysis from A to Z (eds. Cornils, B., Herrmann, W. A., Zanthoff, H.-W. & Wong, C.-H.) 2134–2135 (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2013).

Boudart, M. Heterogeneous catalysis by metals. J. Mol. Catal. 30, 27–38 (1985).

Boudart, M. Catalysis by supported metals. Adv. Catal. 20, 153–166 (1969).

Che, M. & Bennett, C. O. The influence of particle size on the catalytic properties of supported metals. Adv. Catal. 36, 55–171 (1989).

van Santen, R. A. Complementary structure sensitive and insensitive catalytic relationships. Acc. Chem. Res. 42, 57–66 (2009).

Nørskov, J. K. et al. The nature of the active site in heterogeneous metal catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 2163–2171 (2008).

Horiuti, I. & Polanyi, M. Exchange reactions of hydrogen on metallic catalysts. Trans. Faraday Soc. 30, 1164–1172 (1934).

Cortright, R. D., Goddard, S. A., Rekoske, J. E. & Dumesic, J. A. Kinetic study of ethylene hydrogenation. J. Catal. 127, 342–353 (1991).

Jung, U. et al. Comparative in operando studies in heterogeneous catalysis: atomic and electronic structural features in the hydrogenation of ethylene over supported Pd and Pt catalysts. ACS Catal. 5, 1539–1551 (2015).

Godbey, D., Zaera, F., Yeates, R. & Somorjai, G. A. Hydrogenation of chemisorbed ethylene on clean, hydrogen, and ethylidyne covered platinum (111) crystal surfaces. Surf. Sci. 167, 150–166 (1986).

Avanesian, T. et al. Quantitative and atomic-scale view of CO-induced Pt nanoparticle surface reconstruction at saturation coverage via DFT calculations coupled with in situ TEM and IR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 4551–4558 (2017).

Kale, M. J. & Christopher, P. Utilizing quantitative in situ FTIR spectroscopy to identify well- coordinated Pt atoms as the active site for CO oxidation on Al2O3‑supported Pt catalysts. ACS Catal. 6, 5599–5609 (2016).

Meirer, F. & Weckhuysen, B. M. Spatial and temporal exploration of heterogeneous catalysts with synchrotron radiation. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 324–340 (2018).

Vogt, C. et al. Unravelling structure sensitivity in CO2 hydrogenation over nickel. Nat. Catal. 1, 127–134 (2018).

Socrates, G. Infrared and Raman Characteristic Group Frequencies. (Wiley, Hoboken, 2001).

Lundwall, M. J., McClure, S. M. & Goodman, D. W. Probing terrace and step sites on Pt nanoparticles using CO and ethylene. J. Phys. Chem. C. 114, 7904–7912 (2010).

Tilekaratne, A., Simonovis, J. P., López Fagúndez, M. F., Ebrahimi, M. & Zaera, F. Operando studies of the catalytic hydrogenation of ethylene on Pt(111) single crystal surfaces. ACS Catal. 2, 2259–2268 (2012).

Zaera, F. & Somorjai, G. A. Hydrogenation of ethylene over platinum (111) single-crystal surfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 106, 2288–2293 (1984).

Cargnello, M. et al. Control of metal nanocrystal size reveals metal-support interface role for ceria catalysts. Science 341, 771–773 (2013).

Martin, D. J. et al. Reversible restructuring of supported Au nanoparticles during butadiene hydrogenation revealed by operando GISAXS/GIWAXS. Chem. Commun. 53, 5159–5162 (2017).

Somorjai, G. A. The flexible surface: new techniques for molecular level studies of time dependent changes in metal surface structure and adsorbate structure during catalytic reactions. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 107, 39–53 (1996).

Yang, Y., Zhang, H. & Douglas, J. F. Origin and nature of spontaneous shape fluctuations in “small” nanoparticles. ACS Nano 8, 7465–7477 (2014).

Siegel, D. J. & Hamilton, J. C. Computational study of carbon segregation and diffusion within a nickel grain boundary. Acta Mater. 53, 87–96 (2005).

Lander, J. J., Kern, H. E. & Beach, A. L. Solubility and diffusion coefficient of carbon in nickel: Reaction rates of nickel-carbon alloys with barium oxide. J. Appl. Phys. 23, 1305–1309 (1952).

Cremer, P. S., Su, X. C., Shen, Y. R. & Somorjai, G. A. Ethylene hydrogenation on Pt(111) monitored in situ at high pressures using sum frequency generation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 2942–2949 (1996).

Somorjai, G. A. The structure sensitivity and insensitivity of catalytic reactions in light of the adsorbate induced dynamic restructuring of surfaces. Catal. Lett. 7, 169–182 (1990).

Somorjai, G. A. & Carrazza, J. Structure sensitivity of catalytic reaction. Ind. Eng. Chem. Fundam. 25, 63–69 (1986).

Ermakova, M. A. & Ermakov, D. Y. High-loaded nickel-silica catalysts for hydrogenation, prepared by sol-gel route: structure and catalytic behavior. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 245, 277–288 (2003).

de Jong, K. P. Deposition precipitation. In Synthesis of Solid Catalysts (ed. de Jong, K. P.) 111–134 (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2009).

Lok, M. Coprecipitation. In Synthesis of Solid Catalysts (ed. de Jong, K. P.) 135–151 (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank NWO and BASF for a TA-CHIPP grant. B.M.W. also thanks NWO for a Gravitation program (Netherlands Center for Multiscale Catalytic Energy Conversion (MCEC)) and ARC-CBBC for research funding. A.I.F. acknowledges support of the U.S. DOE BES Grant No. DE-SC0022199. C. V. acknowledges support of a Niels Stensen Fellowship. Roeland Dijkema, Vincent Laban, Aaike van Vugt and Tobias Pfeiffer of VSParticle are thanked for their help to prepare in-situ TEM samples via spark ablation. Alicja Kahlan (UU) is thanked for help in measuring FT-IR in ethene hydrogenation experiments. Florian Zand (UU) is thanked for help in the sample preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.V. conceptualized the project, while under supervision of B.M.W.. E.G. synthesized the catalysts. M.N. helped to design, perform and analyze quick-XAS experiments, D.F. the modulated excitation experiments. R.v.S. provided useful discussions to the structure (in)sensitivity theory with B.M.W. and C.V.. R.U. performed and helped analyze the HR-TEM experiments at Oakridge National Laboratory with C.V.. A.I.F. provided discussions with respect to EXAFS fitting and modeling, and theorized C-fraction and intercalation in discussion with F.M. and C.V.. F.M. and M.M. provided day to day validation, discussions, support and helped C.V. to conceptualize ideas and analyze data. B.M.W. supervised, provided resources and discussions to C.V., who performed experiments, and subsequently analyzed and interpreted these data and wrote the manuscript based on discussions with F.M., M.M., R.v.S., A.F. and B.M.W. under final supervision of B.M.W.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vogt, C., Meirer, F., Monai, M. et al. Dynamic restructuring of supported metal nanoparticles and its implications for structure insensitive catalysis. Nat Commun 12, 7096 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-27474-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-27474-3

This article is cited by

-

Dynamic coordination engineering of 2D PhenPtCl2 nanosheets for superior hydrogen evolution

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Interrogating site dependent kinetics over SiO2-supported Pt nanoparticles

Nature Communications (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.