Abstract

Perovskite oxides can host various anion-vacancy orders, which greatly change their properties, but the order pattern is still difficult to manipulate. Separately, lattice strain between thin film oxides and a substrate induces improved functions and novel states of matter, while little attention has been paid to changes in chemical composition. Here we combine these two aspects to achieve strain-induced creation and switching of anion-vacancy patterns in perovskite films. Epitaxial SrVO3 films are topochemically converted to anion-deficient oxynitrides by ammonia treatment, where the direction or periodicity of defect planes is altered depending on the substrate employed, unlike the known change in crystal orientation. First-principles calculations verified its biaxial strain effect. Like oxide heterostructures, the oxynitride has a superlattice of insulating and metallic blocks. Given the abundance of perovskite families, this study provides new opportunities to design superlattices by chemically modifying simple perovskite oxides with tunable anion-vacancy patterns through epitaxial lattice strain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In oxides, the introduction of anion vacancies brings about a diversity of chemical and physical properties; the most widely being studied in perovskite oxides1,2,3. If the anion-vacancy concentration (δ in ABO3–δ) is a rational fraction of the oxygen stoichiometry in the unit cell, the vacancies tend to aggregate to form linear or planar defects. For example, fast oxygen diffusion in BaInO2.5 (δ = 1/2) results from oxygen-vacancy chains4. In SrFeO2 (δ = 1), (001)p defect planes of the original perovskite cell allow metal-metal bonding between square-planar Fe(II) centers, leading to a half-metallic state under pressure5. The superconducting Tc in cuprates strongly depends on the number of CuO2 sheets made by introducing (001)p defect planes6. Compounds having such anion-defect chains or planes can be synthesized through a variety of approaches such as cationic substitution7, topochemical and electrochemical reactions8,9, and under appropriate conditions (temperature10, gaseous atmosphere11, or pressure12).

Concurrently, advances in the materials science of perovskite-based systems has been amplified with the development of single-crystal (epitaxial) thin films. In particular, lattice strain through a mismatch between the underlying substrate and the deposited film is a key parameter that has been extensively studied. Strain-driven phenomena has led to charge/orbital order in La1−xSrxMnO313, improved ferroelectricity in BaTiO314, multiferroicity in EuTiO315, and superconductivity in La1.9Sr0.1CuO4 (ref. 16). Furthermore, a ferroelectric response in tensile-strained SrTaO2N films is ascribed to a change in local coordination geometry17. The lattice mismatch also allows for the introduction of random oxygen vacancies18,19,20,21. Controlling vacancy ordering of perovskite oxides have also been reported22,23,24,25,26,27, but these efforts are limited to controlling crystallographic orientation of the deposited films such as Ca2Fe2O5 brownmillerite.

In this study, we show a low-temperature reaction of SrVO3 (600 °C in NH3 gas) topochemically transforming to SrVO2.2N0.6 (δ = 0.2) with regular (111)p anion-vacancy planes. This is already a surprising observation as such anion-vacancy order has never been seen in oxynitrides. The crystal and electronic structure of SrVO2.2N0.6 is mainly two-dimensional, with conducting octahedral layers separated by insulating tetrahedral layers. Most surprisingly, the same ammonia treatment of an epitaxial SrVO3 film on different substrates can change the periodicity of the (111)p plane, or can even alter the direction of anion-vacancy plane to (112)p, which is distinct from the previous efforts22,23,24,25,26,27 where the crystallographic orientation of the film is altered depending on the substrates. This observation suggests that lattice strain can be used to induce and manipulate the anion-vacancy planes and provide a controllable parameter for the development of exotic structural and electronic states in perovskite films.

Results and discussion

A (111)p superlattice in nitridized SrVO3

Oxynitrides (oxide-nitrides) exhibit attractive properties including visible-light responsive photocatalysis28, but the highly reducing atmosphere of high-temperature reaction with ammonia (ammonolysis) often makes it difficult to obtain the desired structures29. Anion-vacancy order, which is common in oxides, has not been reported in oxynitrides. Recently, low-temperature ammonolysis (≤500 °C) using oxyhydrides has been proven to be a useful approach to access highly nitridized BaTiO3 through topochemical H/N exchange (e.g., BaTiO2.4N0.4 from BaTiO2.4H0.6)30. Subsequently, ammonolysis at moderate temperatures (~800 °C) has been shown to promote topochemical O/N exchange (EuTiO2N from EuTiO2.8H0.2)31. The present study extends these approaches to a vanadium oxyhydride32. When reacted at low temperature, 300 °C, in NH3, SrVO2H is topochemically converted into a cubic perovskite SrVO2.7N0.2 (Supplementary Note 1, Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2 and Supplementary Table 1). In contrast to the titanium case, even the pristine oxide SrVO3 can be partially nitridized at 500 °C resulting in SrVO2.85N0.1, while the nitrogen content is lower than that obtained from SrVO2H at 300 °C (Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). Both oxynitrides carry tetravalent vanadium ions.

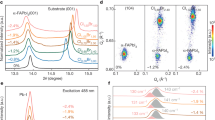

With a moderate increase in the ammonolysis temperature to 600 °C, the ex situ X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of SrVO3 and SrVO2H become drastically different (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1), although the sample color remains black. Since the XRD profiles are very similar, the data for the SrVO3-derived sample will be shown in the main body of the manuscript. The resulting structure has a rhombohedral cell (a = 5.51 Å and c = 34.3 Å), similar to that of 15R-type perovskite SrCrO2.8 (Sr5Cr5O14) with oxygen-vacancy order along (111)p33. The topochemical nature of the reaction is verified by ammonolysis reactions of Sr2V2O7 above 600 °C, which yielded Sr3V2O8 as the main product (Supplementary Fig. 1c). The 15R phase decomposes under NH3 above 800 °C.

a XRD patterns of precursor SrVO3 with the cubic perovskite structure (red, top) and the one ammonolized at 600 °C (blue, middle). A simulation pattern of 15R-SrCrO2.8 (a = 5.51 Å and c = 34.5 Å)33 is shown for comparison (black, bottom). b, c The structural change from SrVO3 (b) to 15R-SrVO2.2N0.6 (Sr5V5O11N3) with anion vacancies in every fifth (111)p layer, leading to the (ooott)3 stacking sequence (c). Sr atoms are omitted for simplicity. Black lines in each structure represent the unit cell.

Rietveld refinement to the synchrotron XRD data was carried out assuming the 15R-structure33 for SrV(O,N)2.8 within the R−3m space group (Supplementary Note 1, Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2). A subsequent neutron refinement enabled us to determine the anion distribution between N and O, where the site fractional occupancies (g) was constrained to gO + gN = 1. This analysis concluded that the isolated tetrahedral (6c) site is fully occupied by oxygen (gO1 = 1), while nitrogen atoms are partially populated at the 18h sites (gN2 = 0.325(8) ≈ 1/3 and gN3 = 0.173(5) ≈ 1/6), resulting in the average chemical formula SrVO2.203(8)N0.597(8). X-ray and neutron refinement for the SrVO2H-derived sample gave similar results, with a composition of SrVO2.22(5)N0.58(5) (Supplementary Note 1, Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 3). Combustion analysis validated the total nitrogen content (Supplementary Note 1). We thus concluded that the composition is SrVO2.2N0.6 (Sr5V5O11N3).

15R-SrVO2.2N0.6 contains one-third of the anion vacancies in every fifth SrO3 (111)p planes and the residual oxide anions in the SrO2 plane are re-organized to form a double-tetrahedral layer (Fig. 1c). Bond valence sum calculation for the tetrahedral (V1) site gave a value close to 5 (+5.1), while those for the octahedral (V2, V3) sites are +3.6 and +3.8 (Supplementary Table 4). The average valence of +4.2 well agrees with the value expected from the chemical composition. This valence assignment is fully supported by 51V-NMR as shown later. The transformation of SrCrO3 to 15R-SrCrO2.8 can be understood by the crystal field stabilization of Cr4+ (d2) in tetrahedral coordination33. Since the tetrahedral vanadium in our case is exclusively pentavalent34,35,36, the tetrahedral coordination preference should also be the origin of this phase stabilization where SrV4+O3 (or SrV4+O3–2x/3Nx) is oxidized by aliovalent N3–/O2– exchange. Although diffusion of nitride anions requires larger activation energy relative to oxide anion37, perovskite-based compounds with AO2 layers have shown rapid oxide ion conduction38,39,40. In this regard, the diffusion of the nitride ions might be promoted by “in situ” formation of SrO2 layers during the ammonolysis reaction at 600 °C.

Two-dimensional electronic states

The cubic perovskite SrVO3 has a single V4+ site and is characterized as a Pauli paramagnetic metal with a 3D Fermi surface41. However, the insertion of periodic anion-vacancy layers in SrVO3 results in a dramatic change of its physical properties. The 51V-NMR spectrum of 15R-SrVO2.2N0.6 powder can be fitted with a sharp and a broad component (Fig. 2a). The former is centered at μ0H(T) = 1.4270 T, which is identical to Sr3V5+2O8 and hence assigned to the tetrahedral V1. This site has an extremely slow relaxation time of 1/T1 = 0.06 s–1 (Fig. 2b), indicating that 3d electrons are totally absent for this electronic configuration. Further, the very sharp peak implies a “strict” V1O3N configuration though anion order within the SrO2N layer is not seen from the diffraction study. By contrast, the broad component centered at 1.4243 T (cf. 1.4245 T in SrVO3) has a much faster relaxation rate (1/T1 = 10.55 s–1), and is assigned to the octahedral (V2, V3) sites.

a Field-swept NMR spectrum at 30 K showing peaks from tetrahedral (orange) and octahedral (red) sites. Solid circle indicates the signal from the Cu coil. The orange and red arrows indicate the positions at which 1/T1 was measured. Inset is an enlarged plot, where spectra of SrVO3 and Sr3V2O8 are shown for comparison. b Time after saturation pulse dependence of relaxation of R(t) ≡ [m(∞) – m(t)]/m(∞)], where m represents nuclear magnetization at a time t after a saturation pulse, at the tetrahedral (orange) and octahedral (red) sites. The lines are the fit to extract the time constant. Tetrahedral data with t < 100 ms were not considered due to octahedral-site contribution (see yellow arrow in a).

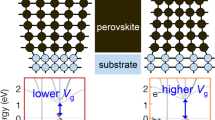

These results indicate that the triple-octahedral layer is electronically well separated by the double-tetrahedral layer. This is verified through our density functional theory (DFT) calculations that show a 2D Fermi surface with two cylinder-like sheets (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Note 2), in stark contrast to the precursor SrVO3 with its 3D Fermi surface41. Closer inspection shows that there are three pairs of flat Fermi surfaces, implying weak overlap between different t2g orbitals. A similar feature can be seen in the (111) SrTiO3 surface 2D electron gas (2DEG)42. NMR spectra of the octahedral site exhibit splitting at 5 K, accompanied by a divergence in 1/T1T (Figs. 3b, c). The ordered moment is as low as 0.01μB (where the hyperfine coupling of –7.4 T μB−1 for LiV2O4 was used41), indicating itinerant antiferromagnetism. The magnetic origin of the transition is also observed in field-dependent electrical resistance of the nitridized SrVO3 film on SrTiO3 (111) (Fig. 3d). These experimental findings, together with theoretically obtained 2D Fermi surfaces, strongly suggest that the observed transition is a spin density wave (SDW) transition owing to the large nesting effect43.

a Calculated Fermi surface for 15R-SrVO2.2N0.6. b 51V-NMR spectra for SrVO2.2N0.6 at low temperatures. The ordered moment is estimated to be <0.01μB. c Temperature dependence of 1/T1T at the octahedral site (red arrow in a), indicating a magnetic transition at 5 K. Error bars are standard deviation. d Temperature dependence of electrical resistance of the nitridized SrVO3 film on SrTiO3 (111) at 0T and 7T, characteristic of weak antiferromagnetism due to SDW transition at around 8 K.

Strain-induced defect layer switching

As demonstrated above, polycrystalline 15R-SrVO2.2N0.6 possesses (111)p defect planes with the fivefold periodicity (namely, the ooott sequence where “o” and “t” refer to octahedral and tetrahedral layers). In order to investigate the epitaxial strain effects on oxynitrides, we fabricated an epitaxial SrVO3 thin film using a (111)-oriented substrate for subsequent ammonolysis. Surprisingly, thermal treatment (NH3 gas, 600 °C) of the SrVO3 film on an LSAT (111) substrate resulted in the creation of new anion-defect layers. Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) clearly indicated a (112)p planar defect, as shown in Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 4a for high-angle annular dark field (HAADF) and annular bright-field (ABF) images. The Fourier transform data shows sevenfold satellite peaks along [112]p. Based on STEM and XRD along with simulation, we constructed a monoclinic structure 7M-SrV(O,N)2.71 (Sr14V14(O,N)38) with tetrahedra and pyramids around anion defects (Supplementary Note 3, Fig. 4a, c, e, Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Tables 5 and 6), meaning that the composition is slightly different from the bulk composition of SrVO2.2N0.6. A similar (112)p planar defect has recently been reported in BaFeO2.33F0.33 (Ba3Fe3O7F) powder, but with a threefold periodicity44. Nuclear reaction analysis (NRA) and elastic recoil detection analysis (ERDA), respectively, gave the nitrogen content of x = 0.8(2) and 0.54(3) in SrVO2.71–xNx. Note that the oxynitride films have threefold domain structures related by 120° rotation (Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4h–j).

a, b Cross-sectional HAADF image of the nitridized SrVO3 film on a LSAT (111) and b SrTiO3 (111) interfaces taken along \([1\bar 10]\) and their Fourier transform patterns. c, d The corresponding structures with vacancies along (c) (112)p and (d) (111)p with the oooott sequence (see Fig. 1c for the bulk). Sr atoms are omitted. e Experimental and simulated ABF images of the structure in c. f Schematic view of biaxial strain-induced switching of anion-vacancy layers. Red lines represent vacancy layers. g Thermodynamic competition between SVON-111 and -112 as a function of biaxial strain. DFT-calculated free energies of SVON-111 and SVON-112 under flowing NH3(g) at 600 °C, as a function of the Sr−Sr distance. The corresponding cation-cation distances for LaAlO3 and SrTiO3 substrates are also given.

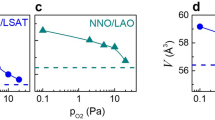

Despite extensive research on perovskite oxides, conversion of oxygen-vacancy planes via thin film fabrication has not been previously observed. Past studies on thin films have been exclusively limited to increasing random oxygen vacancies18,19,20,21 or controlling the crystallographic orientation of known defect perovskites such as Ca2Fe2O5 brownmillerite22,23,24,25,26,27. Given a lattice mismatch of –0.7% between 15R-SrVO2.2N0.6 and LSAT (111), it is naturally expected that the observed (111)p to (112)p switching arises as a result of the compressive biaxial strain from the substrate. For a proof-of-concept, we grew epitaxial SrVO3 films on LaAlO3 (111) (LAO) and SrTiO3 (111) (STO) substrates and nitridized under the same condition (Supplementary Note 4). For the LAO (111) substrate with a nominal strain of −2.3%, although the film was partially relaxed to about −1.0%, we observed (112)p defect planes with a sevenfold superlattice (Supplementary Fig. 5), as in the case of LSAT substrate. On the contrary, when an STO (111) substrate with 0.2% tensile strain was used, we observed (111)p defect planes (Fig. 4b). These results strongly support that the vacancy-plane switching originates from substrate strain (Fig. 4g).

To rationalize the formation of 7M-SrV(O,N)2.71 on LaAlO3 (SVON-112) versus 15R-SrVO2.2N0.6 in the bulk (SVON-111), we used DFT to calculate the relative energies of the two SVON orientations at various biaxial lattice strains. For these calculations, we used the SCAN metaGGA functional45, which is more accurate in computing thermochemical properties than the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional46,47. For SVON-112, we assumed a plausible distribution of N and O (to give Sr7V7O14N5) with reference to SVON-111 (Supplementary Note 5). The free energy of strained SVON is modeled using a thermodynamic grand potential45, with chemical potentials of μN and μO set to approximate NH3(g) flow rates at 200 mL min−1 at 600 °C, as benchmarked by Katsura et al. (Supplementary Fig. 9)46. Figure 4f and Supplementary Fig. 10 demonstrate that the SVON-112 structure is stabilized when compressive isotropic biaxial strain is applied, with the minimum energy at the position close to the La–La distance of LaAlO3 (dLa–La = 5.390 Å), consistent with the experiment. On the other hand, at the Sr–Sr distance of SrTiO3 (dSr–Sr = 5.579 Å), the minimum free energy SVON compound is SVON-111. Further details of the calculation can be found in Supplementary Note 5.

Further insights are garnered from observation that the oxynitride film grown on SrTiO3 (111) exhibits sixfold superlattice reflections in TEM and XRD (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 6), implying that the defect plane appears in every six SrO3 layer, namely, the oooott sequence (Fig. 4d), in contrast to the (ooott)3 sequence in the bulk (Fig. 1c). This observation suggests that even small strains (0.2%) may affect the structure, offering fine and extensive tuning of not only the direction but also the periodicity (density) of anion-defect layers (Fig. 4g), which will alter the chemical and physical properties. The slightly higher SDW transition temperature of 8 K for this film (Fig. 3d) compared with the bulk (5 K) might also be related to the periodicity change. We carried out similar reactions to the SrVO3 films grown along [001] using LSAT and LaAlO3 substrates. However, these films were nitridized without forming superlattices (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8), indicating that the strain direction, or how the VO6 octahedron is deformed greatly affects the vacancy-layer formation (or not). Recent first-principles study on LaAlO3 showed epitaxial strain in the (001) and (111) planes results in distinct phases with different octahedral rotation patterns47.

The observed periodicity change may also be subject to kinetic aspects. It is shown that brownmillerite CaFeO2.5 films with tetrahedral/octahedral layers stacked parallel and perpendicular to a substrate display distinct reactivities with anisotropic oxygen diffusions25. Upon the reduction of CaFeO2.5 films to CaFeO2, oxide anions are prone to migrate perpendicular to the substrate. Our oxynitride films on STO (111) are overall epitaxial but the superlattice is slightly corrugated (Fig. 4b) unlike films with (112)p defect planes (Fig. 4a). Such corrugation might arise from faster oxygen extraction and nitrogen insertion perpendicular to the substrate and also be a cause for the elongated periodicity from five- to sixfold. If this is the case, the reaction temperature and time could also be parameters to tune anion-vacancy order patterns. It would be of further interest to see if—or how—the film thickness also plays a role in the resulting lattice periodicity/structure.

In the last two decades, there has been tremendous progress in the study of artificial perovskite superlattice of at least two sets of perovskite compositions (SrTiO3/LaAlO3, LaMnO3/SrMnO3, etc.), leading to the discovery of novel phenomena such as superconductivity and quantum Hall effects in 2DEG48,49,50,51. Given the abundance of perovskite oxides forming linear and planar anion defects, it is clear that the present study offers exciting new opportunities to design perovskite superlattices by chemically modifying simple 3D perovskite oxides with controllable anion-vacancy planes through the lattice strain in order to obtain unique properties and phases such as 2DEG. Furthermore, in an even broader perspective not just limited to oxides, the vacancy engineering we demonstrated here might also be utilized for phonon control and to strongly modify thermal transport properties given less controlled approaches to yield record thermoelectric performance in commercial materials such as B0.5Sb1.5Te3 and PbSe52,53.

Methods

Preparation of powder samples

Sr2V2O7 was prepared by solid state reactions. Stoichiometric mixtures of SrCO3 (99.9%; High Purity Chemicals) and V2O5 (99.99%; Rare Metallic) were ground, pelletized, and preheated at 900 °C in air for 48 h with intermediate grindings. SrVO3 was obtained by annealing the Sr2V2O7 pellet at 900 °C in flowing H2−Ar (10:90 vol%) gas at a rate of 100 mL min−1 for 24 h. SrVO2H was prepared by a topochemical reaction of SrVO3 with CaH2 (99.99%; Sigma-Aldrich) as described elswhere32. Ammonolysis reactions were performed for SrVO2H, SrVO3, and Sr2V2O7; the powder samples on a platinum boat were placed in a tubular furnace (inside diameter of 26 mm) and were reacted under NH3 flow (200 mL min−1) at various temperatures (300–800 °C) for 12 h, at a heating and cooling rate of 100 °C h−1. Before reaction, the tube was purged with dry N2 gas at ambient temperature to expel oxygen and moisture.

Characterization of powder samples

We conducted XRD measurements using a D8 ADVANCE diffractometer (Burker AXS) with a Cu Kα radiation. The nitrogen contents of the samples after different NH3 treatments were determined by the combustion method (elemental analysis) at Analytical Services, School of Pharmacy, Kyoto University. Approximately 2 mg was used for each experiment, and three data sets were averaged. A high-resolution synchrotron XRD experiment for the nitridized samples was performed at room temperature using the large Debye–Scherrer cameras with a semiconductor detector installed at the beamline BL02B2 (JASRI, SPring-8). Incident beams from a bending magnet were monochromatized to λ = 0.42073(1) and 0.78086(2) Å for the SrVO3 samples after NH3 treatment at 300 and 600 °C, respectively. Finely ground powder samples were sieved through a 32-μm mesh sieve and were packed into Pyrex capillaries with an inner diameter of 0.2 mm, which were then sealed. The sealed capillary was rotated during measurements to improve randomization of the individual crystallite orientations. Powder neutron diffraction data were collected at room temperature using the high-resolution powder diffractometer BT-1 (λ = 1.54060 Å) at the NIST Center for Neutron Research (NCNR), and time-of-flight (TOF) diffractometers, iMATERIA54, and NOVA at the Japan Proton Accelerator Research Complex (J-PARC). The collected synchrotron and neutron profiles were analyzed by the Rietveld method using RIETAN-FP program55 (SPring-8 and NIST) and Fullprof program56 (J-PARC).

Preparation of thin film samples

Epitaxial SrVO3 thin films with a thickness of 100 nm were deposited on single crystalline substrates of SrTiO3 (111), (LaAlO3)0.3(SrAl0.5Ta0.5O3)0.7 (LSAT) (111), LaAlO3 (111), (LSAT) (100), and LaAlO3 (100), using the pulsed laser deposition technique. We used a KrF excimer laser at λ = 248 nm, with a deposition rate of 2 Hz and an energy of ~2 J cm−2. The substrate temperature was kept at 950 °C during the deposition, with an oxygen partial pressure of 5 × 10–7 Pa. Subsequently, the oxide films were placed in a platinum boat in a tubular furnace and heated under an NH3 flow at 600 °C (LSAT (111)) and 620 °C (SrTiO3 (111), LaAlO3 (111), LSAT (100), and LaAlO3 (100)) for 12 h, in the same manner as in the case of the powder samples.

Characterization of thin films

Structures of the films were examined by XRD with Cu Kα radiation (Bruker AXS D8 DISCOVER), where the diffractometer in parallel beam geometry was equipped with one- and two-dimensional detectors. STEM images were acquired using an aberration-corrected microscope (Titan cubed, FEI) operating at an acceleration voltage of 300 kV. The convergence semiangle of the incident probe was 18 mrad, while the detector collection semiangles ranged from 77 to 200 mrad for HAADF and 10–19 mrad for ABF imaging. The high-resolution STEM images in Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 4 were Fourier filtered for noise reduction. A thin specimen for the STEM observation was prepared using a focused ion beam (FIB) instrument (FB-2000, Hitachi). A low-energy Ar-ion milling (NanoMill Model1040, E.A. Fischione Instruments) was performed after the FIB processing to eliminate surface damaged layers.

The amount of nitrogen in the oxynitride film was evaluated by NRA method using the 15N(p,αγ)12C resonant nuclear reaction at 899.98 keV. NRA measurements were carried out with a 1-MV tandetron accelerator at Tandem Accelerator Complex, University of Tsukuba. The experimental error of around ±20% originates from instability of accelerator and small thickness of the film. Details of the measurement and calibration are given in ref. 17.

The anion compositions of the films were also determined by ERDA with a 38.4 MeV Cl beam generated by a 5-MV tandem accelerator (Micro Analysis Laboratory, The University of Tokyo [MALT])57. The experimental errors were around 5% under a typical condition.

Physical property measurements

A conventional spin-echo technique was used to measure 51V-NMR for the powder sample of 15R-SrVO2.2N0.6. 51V-NMR spectra (the nuclear spin of I = 7/2 and the nuclear gyromagnetic ratio of 51γ/2π = 11.193 MHz T−1) were obtained by sweeping magnetic field in a fixed frequency of 15.9 MHz. Nuclear spin–lattice relaxation rate 1/T1 was determined by fitting the time variation of the nuclear magnetization m(t) after a saturation pulse to a theoretical function for a nuclear spin I = 7/2 relaxation at the central transition. The electrical resistance of the nitridized SrVO3 film on SrTiO3 (111) was measured down to 2 K by means of a standard four-probe method using a physical property measuring system (Quantum Design, PPMS) at 0 and 7 T.

DFT calculations

Crystal structure optimization for 15R-SrVO2.2N0.6 was performed by using the PBE parametrization of the generalized gradient approximation58 and the projector augmented wave method (PAW)59 as implemented in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)60,61,62,63. In the PAW potentials used in this study, the following states are treated as core for each element: [Ar] 3d10 for Sr, [Ne] for V, and [He] for O and N, which is in common with the strain calculation described in the next paragraph and Supplementary Note 5. In order to obtain further information of the electronic structure, we performed band-structure calculation using the WIEN2k code64 and then extracted the vanadium-d Wannier functions from the calculated band structures using the Wien2Wannier and Wannier90 codes65,66,67,68. For this purpose, we also used the PBE functional. Further details of these calculations are discussed in Supplementary Note 2.

For the biaxial strain calculations, ordered approximants for 7M-SrV(O,N)2.71 and 15R-SrVO2.2N0.6 were generated in pymatgen69. Stability calculations were performed using VASP, with the SCAN metaGGA functional70. The relative free energies of the 7M and 15R phase for a given temperature, ammonia flow rate, and biaxial strain, are calculated using a thermodynamic grand potential, Φ, as

where the chemical potentials, μ, of oxygen and nitrogen are determined from benchmarked nitrogen activities by Katsura46; further details of this referencing is discussed in Supplementary Note 5. For both SVON (111) and (112) orientations, we first relax the unit cell until forces are converged to 10–8 eV Å−1, and then we perform the slab transformation into (111) or (112) Miller indices and apply isotropic biaxial strain.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Schooley, J. F., Hosler, W. R. & Cohen, M. L. Superconductivity in semiconducting SrTiO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 12, 474–475 (1964).

Sanchez, R. D. et al. Metal-insulator transition in oxygen-deficient LaNiO3-x perovskites. Phys. Rev. B 54, 16574–16578 (1996).

Mefford, J. T. et al. Water electrolysis on La1-xSrxCoO3-δ perovskite electrocatalysts. Nat. Commun. 7, 11053 (2016).

Goodenough, J. B., Ruiz-Diaz, J. E. & Zhen, Y. S. Oxide-ion conduction in Ba2In2O5 and Ba3In2MO8 (M = Ce, Hf, or Zr). Solid State Ion. 44, 21–31 (1990).

Kawakami, T. et al. Spin transition in a four-coordinate iron oxide. Nat. Chem. 1, 371–376 (2009).

Takayama-Muromachi, E. High-pressure synthesis of homologous series of high critical temperature (Tc) superconductors. Chem. Mater. 10, 2686–2698 (1998).

Anderson, M. T., Vaughey, J. T. & Poeppelmeier, K. R. Structural similarities among oxygen-deficient perovskites. Chem. Mater. 5, 151–165 (1993).

Hayward, M. A., Green, M. A., Rosseinsky, M. J. & Sloan, J. Sodium hydride as a powerful reducing agent for topotactic oxide deintercalation: synthesis and characterization of the nickel (I) oxide LaNiO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 8843–8854 (1999).

Le Toquin, R., Paulus, W., Cousson, A., Prestipino, C. & Lamberti, C. Time-resolved in situ studies of oxygen intercalation into SrCoO2.5, performed by neutron diffraction and X-ray absorption spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 13161–13174 (2006).

Takeda, Y., Kanno, K. & Takada, T. Phase relation in the oxygen nonstoichiometric system, SrFeOx (2.5 ≤ x ≤ 3.0). J. Solid State Chem. 63, 237–249 (1986).

Suescun, L., Chmaissem, O., Mais, J., Dabrowski, B. & Jorgensen, J. D. Crystal structures, charge and oxygen-vacancy ordering in oxygen deficient perovskites SrMnOx (x < 2.7). J. Solid State Chem. 180, 1698–1707 (2007).

Strobel, P., Capponi, J. J., Chaillout, C., Marezio, M. & Tholence, J. L. Variations of stoichiometry and cell symmetry in YBa2Cu3O7−x with temperature and oxygen pressure. Nature 327, 306–308 (1987).

Konishi, Y. et al. Orbital-state-mediated phase-control of manganites. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 68, 3790–3793 (1999).

Choi, K. J. et al. Enhancement of ferroelectricity in strained BaTiO3 thin films. Science 306, 1005–1009 (2004).

Lee, J. H. et al. A strong ferroelectric ferromagnet created by means of spin-lattice coupling. Nature 466, 954–958 (2010).

Locquet, J. et al. Doubling the critical temperature of La1.9Sr0.1CuO4 using epitaxial strain. Nature 394, 453–456 (1998).

Oka, D. et al. Possible ferroelectricity in perovskite oxynitride SrTaO2N epitaxial thin films. Sci. Rep. 4, 4987 (2014).

Aschauer, U., Pfenninger, R., Selbach, S. M., Grande, T. & Spaldin, N. A. Strain-controlled oxygen vacancy formation and ordering in CaMnO3. Phys. Rev. B 88, 054111 (2013).

Hirai, K. et al. Strain-induced significant increase in metal-insulator transition temperature in oxygen-deficient Fe oxide epitaxial thin films. Sci. Rep. 5, 7894 (2015).

Becher, C. et al. Strain-induced coupling of electrical polarization and structural defects in SrMnO3 films. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 661 (2015).

Chandrasena, R. U. et al. Strain-engineered oxygen vacancies in CaMnO3 thin films. Nano Lett. 17, 794–799 (2017).

Onozuka, T., Chikamatsu, A., Hirose, Y. & Hasegawa, T. Structural and electrical properties of lanthanum copper oxide epitaxial thin films with different domain morphologies. CrystEngComm 20, 5012–5016 (2018).

Rossell, M. et al. Structure of epitaxial Ca2Fe2O5 films deposited on different perovskite-type substrates. J. Appl. Phys. 95, 5145–5152 (2004).

Khare, A. et al. Directing oxygen vacancy channels in SrFeO2.5 epitaxial thin films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 4831–4837 (2018).

Inoue, S. et al. Anisotropic oxygen diffusion at low temperature in perovskite-structure iron oxides. Nat. Chem. 2, 213–217 (2010).

Janghyun, J. et al. Effects of the heterointerface on the growth characteristics of a brownmillerite SrFeO2.5 thin film grown on SrRuO3 and SrTiO3 perovskites. Sci. Rep. 10, 3807 (2020).

Petrie, J. R. et al. Strain control of oxygen vacancies in epitaxial strontium cobaltite films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 1564–1570 (2016).

Maeda, K. (Oxy)nitrides with d0-electronic configuration as photocatalysts and photoanodes that operate under a wide range of visible light for overall water splitting. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 10537–10548 (2013). .

Fuertes, A. Chemistry and applications of oxynitride perovskites. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 3293–3299 (2012).

Yajima, T. et al. A labile hydride strategy for the synthesis of heavily nitridized BaTiO3. Nat. Chem. 7, 1017–1023 (2015).

Mikita, R. et al. Topochemical nitridation with anion vacancy-assisted N3–/O2– exchange. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 3211–3217 (2016).

Denis Romero, F. et al. Strontium vanadium oxide-hydrides: “square-planar” two-electron phases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 7556–7559 (2014).

Arévalo–López, A. M. et al. “Hard–soft” synthesis of SrCrO3-δ superstructure phases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 10791–10794 (2012).

Carrillo–Cabrera, W. & Von Schnering, H. G. Crystal structure refinement of strontium tetraoxo–vanadate (V), Sr3(VO4)2. Z. Kristal. 205, 271–278 (1993).

Clarke, S. J. et al. A first transition series pseudotetrahedral oxynitride anion: synthesis and characterization of Ba2VO3N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 3337–3342 (2002).

Tyutyunnik, A. P., Slobodin, B. V., Samigullina, R. F., Verberck, B. & Tarakina, N. V. K2CaV2O7: a pyrovanadate with a new layered type of structure in the A2BV2O7 family. Dalton Trans. 42, 1057–1064 (2013).

Wolff, H. & Dronskowski, R. Defect migration in fluorite-type tantalum oxynitrides: a first-principles study. Solid State Ion. 179, 816–818 (2008).

Zhang, K. H. L. et al. Reversible nano–structuring of SrCrO3-δ through oxidation and reduction at low temperature. Nat. Commun. 5, 4669 (2014).

Ong, P., Du, Y. & Sushko, P. V. Low–dimensional oxygen vacancy ordering and diffusion in SrCrO3−δ. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 1757–1763 (2017).

Fop, S. et al. Oxide ion conductivity in the hexagonal perovskite derivative Ba3MoNbO8.5. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 16764–16769 (2016).

Yoshida, T. et al. Direct observation of the mass renormalization in SrVO3 by angle resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 146404 (2005).

Walker, S. M. et al. Control of a two-dimensional electron gas on SrTiO3 (111) by atomic oxygen. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 177601 (2014).

Fawcett, E. Spin-density-wave antiferromagnetism in chromium. Rev. Mod. Phys. 60, 209–283 (1988).

Clemens, O. Structural characterization of a new vacancy ordered perovskite modification found for Ba3Fe3O7F (BaFeO2.333F0.333): towards understanding of vacancy ordering for different perovskite–type ferrites. J. Solid State Chem. 225, 261–270 (2015).

Sun, W. et al. Thermodynamic routes to novel metastable nitrogen-rich nitrides. Chem. Mater. 29, 6936–6946 (2017).

Katsura, M. Thermodynamics of nitride and hydride formation by the reaction of metals with flowing NH3. J. Alloy. Compd. 182, 91–102 (1992).

Moreau, M., Marthinsen, A., Selbach, S. M. & Tybell, T. First-principles study of the effect of (111) strain on octahedral rotations and structural phases of LaAlO3. Phys. Rev. B 95, 064109 (2017).

Ohtomo, A. & Hwang, H. A high-mobility electron gas at the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 heterointerface. Nature 427, 423–426 (2004).

Reyren, N. et al. Superconducting interfaces between insulating oxides. Science 317, 1196–1199 (2007).

Thiel, S., Hammerl, G., Schmehl, A., Schneider, C. W. & Mannhart, J. Tunable quasi-two-dimensional electron gases in oxide heterostructures. Science 313, 1942–1945 (2006).

Hwang, H. Y. et al. Emergent phenomena at oxide interfaces. Nat. Mater. 11, 103–113 (2012).

Kim, S. I. et al. Dense dislocation arrays embedded in grain boundaries for high-performance bulk thermoelectrics. Science 348, 109–114 (2015).

Chen, Z. et al. Vacancy-induced dislocations within grains for high-performance PbSe thermoelectrics. Nat. Commun. 8, 13828 (2017).

Ishigaki, T. et al. IBARAKI materials design diffractometer (iMATERIA)—versatile neutron diffractometer at J-PARC. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 600, 189–191 (2009).

Izumi, F. & Momma, K. Three-dimensional visualization in powder diffraction. Solid State Phenom. 130, 15–20 (2007).

Rodríguez–Carvajal, J. Recent advances in magnetic structure determination by neutron powder diffraction. Phys. B 192, 55–69 (1993).

Harayama, I., Nagashima, K., Hirose, Y., Matsuzaki, H. & Sekiba, D. Development of ΔE–E telescope ERDA with 40 MeV 35Cl7+ beam at MALT in the University of Tokyo optimized for analysis of metal oxynitride thin films. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B 384, 61–67 (2016).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal-amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251–14269 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab–initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total–energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Blaha, P. et al. WIEN2k, an augmented plane wave + local orbitals programfor calculating crystal properties. Karlheinz Schwarz, Techn. Universität Wien, Austria (2018).

Mostofi, A. A. et al. wannier90: A tool for obtaining maximally–localised Wannier functions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 178, 685–699 (2008).

Souza, I., Marzari, N. & Vanderbilt, D. Maximally localized Wannier functions for entangled energy bands. Phys. Rev. B 65, 035109 (2001).

Kuneš, J. et al. Wien2wannier: trom linearized augmented plane waves to maximally localized Wannier functions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 181, 1888–1895 (2010).

Marzari, N. & Vanderbilt, D. Maximally localized generalized Wannier functions for composite energy bands. Phys. Rev. B 56, 12847–12865 (1997).

Ong, S. P. et al. Python Materials Genomics (pymatgen): a robust, open-source python library for materials analysis. Comput. Mater. Sci. 68, 314–319 (2013).

Sun, J., Ruzsinszky, A. & Perdew, J. P. Strongly constrained and appropriately normed semilocal density functional. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 036402 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (JP16H06438, JP16H06439, JP16H06440, JP16H06441, JP16K21724, JP17H05481, JP18H01860, 20H00384), CREST (JPMJCR1421), and Project of Creation of Life Innovation Materials for Interdisciplinary and International Researcher Development of MEXT, Japan. W.S. was supported by funding from the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, under contract no. UGA-0-41029-16/ER392000 as a part of the Department of Energy Frontier Research Center for Next Generation of Materials Design: Incorporating Metastability. The synchrotron XRD experiments were performed at the BL02B2 of SPring-8 with the approval of JASRI. The ND experiment was performed at J-PARC and the NIST Center for Neutron Research. We thank the sample environment group at J-PARC MLF for their support on the neutron scattering experiments. We appreciate Mr. Satoshi Ishii, Prof. Kimikazu Sasa, and Dr. Hiroshi Naramoto of Univ. Tsukuba for their assistance in the NRA measurements. Certain commercial equipment, instruments, or materials are identified in this document. Such identification does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology nor does it imply that the products identified are necessarily the best available for the purpose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.Y. and H.K. designed the research. T.Y., N.I., T.N., and F.T. synthesized and characterization of the bulk samples. T.Y., A.C., N.I., H.T., T. Maruyama, M.N., T.N., and T. Hasegawa synthesized and characterization of the thin film samples. S.Y., T. Mori, and K. Kimoto performed STEM experiments. S.K. and K. Ishida performed NMR measurements. M.O. and K. Kuroki performed DFT calculations on the bulk, while W.S. on the strained films. K.F., M.Y., C.M.B., T. Honda, K. Ikeda, and T.O. collected neutron data. M.S. and Y.H. conducted NRA measurements. Y.S., Y.H., and D.S. performed ERDA. All the authors discussed the results. T.Y. and H.K. wrote the manuscript, with comments from all the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Young-Il Kim and other, anonymous, reviewers for their contributions to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamamoto, T., Chikamatsu, A., Kitagawa, S. et al. Strain-induced creation and switching of anion vacancy layers in perovskite oxynitrides. Nat Commun 11, 5923 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19217-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19217-7

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.