Abstract

Introduction

Spinal myxopapillary ependymomas (SME) are rare WHO grade II neoplasms of the spinal cord. Despite their good prognosis, they have a high propensity for metastasis and recurrence, although the presentation of SME as multifocal is uncommon.

Case presentation

Here we describe a rare case of a 34-year-old man who presented with painful bilateral radiculopathy with sexual dysfunction and altered sensation with defecation. The patient also reported worsening weakness of bilateral lower extremities when climbing stairs. Biopsy results revealed multifocal SME in the lumbar and sacral spine that was treated with staged surgical resection and post-operative focal radiation therapy.

Discussion

We discuss and evaluate surgical resection and the role of postoperative radiotherapy for SME. We also review the literature surrounding multifocal SME presenting in adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spinal myxopapillary ependymomas (SME) are variants of ependymomas that arise within the conus medullaris, cauda equina and filum terminale and account for 27% of all spinal ependymomas [1, 2]. Classified as World Health Organization (WHO) grade II tumors, SMEs are generally benign and demonstrate slow progression [3].

SMEs have a male predominance and most commonly affect individuals from 20-40 years old, although 8-20% of all SME cases are pediatric [2, 4]. Symptoms typically precede the diagnosis of SME by months to years and result from the spinal cord or nerve compression manifesting as back pain, weakness and numbness in extremities, sphincter dysfunction and sexual dysfunction [5, 6].

Optimal treatment for SMEs remains unclear. Current recommendations include gross total resection (GTR) with preservation of the tumor capsule when feasible. If GTR is not obtained, adjuvant radiation is usually pursued for local disease control with acceptable outcomes [1, 7, 8]. Using this paradigm, SMEs have a very good prognosis with a 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) of 50% following GTR alone and 75% for surgery followed by radiation [9]. Despite SMEs good prognosis, recurrence is common after GTR (15.5%), occurring usually 3-6 years after resection [6, 7].

Aside from the progression of local residual disease, SMEs have a high propensity for metastasis via cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pathways along the neural axis, resulting in potential cranial and spinal sites of spread [6, 10, 11]. There are many cases of SME resection that demonstrate drop metastasis on follow up, requiring further surgical intervention [10, 12]. Whether or not this phenomenon is more common after subtotal resection or in instances of capsular violation during dissection remains unknown.

While CSF dissemination or “drop metastases” in SME is a known phenomenon, the presentation of an SME with drop metastasis at the time of diagnosis is uncommon, especially in adults. There have been 14 previous cases described in English language publications ranging from 2011 to 2020 of multifocal myxopapillary spinal ependymoma (MPE) diagnosed at initial presentation in adults [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Here we present a case of a 34-year-old male presenting with multifocal myxopapillary ependymomas in the lumbar and sacral spine that underwent staged resection for tumor removal. The patient provided written informed consent and patient information was de-identified.

Case presentation

A 34-year-old man with no past medical history presented to his primary care physician with symptoms of low back pain with bilateral radicular symptoms. The patient initially underwent conservative management with physical therapy for 8 weeks and standard pharmacotherapy of pregabalin for neuropathic pain with minimal improvement in symptoms. However, the symptoms of painful radiculopathy along the right posterolateral leg soon returned and worsened along with the development of new, persistent sexual dysfunction and altered sensation with defecation. The patient also reported worsening weakness of bilateral lower extremities when climbing stairs. On physical examination, the patient demonstrated slightly weakened right lower extremity strength of 4/5 on knee flexion, plantarflexion, and dorsiflexion along with right patellar hyporeflexia.

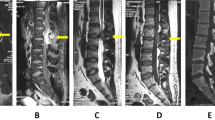

The patient underwent contrast-enhanced MRI of the lumbar spine which demonstrated a homogeneously enhancing intradural, extramedullary lesion extending from mid-L1-L3 level within the anterior intradural space, with an additional smaller enhancing lesion occupying most of the sacral canal, and smaller nodular focus of enhancement at the inferior aspect of the L3 vertebral body within the anterior epidural space (Fig. 1). MRI of the brain and total spine demonstrated no other lesions. Imaging features were consistent with myxopapillary ependymoma and the decision was made to proceed with surgical intervention in a staged fashion. The conus lesion was targeted in the first stage given the size of the lesion, the patient’s symptoms, and its proximity to the conus.

Pre-operative T1 weighted MRI with contrast (A) and T2 weighted MRI without contrast (B) demonstrating the intradural extramedullary lesions extending from mid L1-L2 to L3 level within the anterior intradural space and an additional smaller enhancing lesion occupying the majority of the sacral. Post-operative T1 weighted MRI with contrast (C) and T2 weighted MRI without contrast (D) after two staged resections of the lesion.

The patient underwent T12-L3 laminectomy and resection of the largest component of the tumor during the first stage of the procedure. The tumor was noted to be arising from the filum terminale and was removed en bloc in standard fashion by sectioning the filum terminale proximal and distal to the lesion. The frozen section was consistent with myxopapillary ependymoma. The filum was followed to the small satellite lesion which was noted to be arising from a nerve root suggesting its origin as a drop metastasis. The decision was made to delay the second stage pending final pathology.

Post-operatively the patient recovered without any complications, and postoperative MRI showed resection of spinal canal lesion extending from L1-L2 and the nodular enhancement at L3 with associated postsurgical changes (Fig. 1). There was no evidence of residual nodular enhancing lesion to suggest residual tumor at these levels.

Approximately five weeks later, the patient underwent L5-S1 laminectomies for resection of the sacral disease. Tumor in the sacrum was noted to be diffuse and not attached directly to the film. Tumor was debulked extensively, but ultimately small, residual disease was left along the exiting S2 nerve roots bilaterally.

Post-operatively, the patient did well with resolution of back and leg pain but with persistent difficulty with erectile dysfunction and perianal sensation. He received focal radiation therapy to his spine from L1-S2 level to a dose of 5400 cGy in 30 fractions using 180 cGy per fraction, beginning 6 weeks after his surgery. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) was used to minimize the radiation dose to critical structures including the intestine, kidney, bone, and bone marrow (Fig. 2). Image guidance was used to verify the accuracy of radiation delivery daily during his treatment. At 6-month follow-up, the patient reported new right lower back pain that radiated to the front of his inner thigh and to the back of the knee. The patient denies any weakness or difficulty with ambulation, and endorses improved bowel and bladder incontinence, with very rare episodes of bladder incontinence. Sexual (erectile) dysfunction has not improved from the surgery. The Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS), measured at the beginning of radiation treatment, was 90 and remained so throughout radiation treatment. The patient was referred to a pain specialist and urologist for further follow-up.

Discussion

MPEs are a subtype of ependymomas, which are the most common primary tumors of the spinal cord. They arise from ependymocytes—glial cells that line the ventricles in the brain and the central canal in the spinal cord. Ependymomas were originally considered as four subtypes based on pathological characteristics, including subependymomas, myxopapillary, anaplastic and conventional ependymomas; further broken down into the cellular, papillary, clear cell, and tanycytic types [6, 13]. Recently, characterization has changed according to the WHO 2021 classification of tumors. Ependymomas are now classified by a combination of histopathological characteristics, molecular features, and anatomic location. Additionally, papillary, clear cell, tanycytic, and anaplastic ependymomas are no longer listed as subtypes in the WHO 2021 classification. MPEs, previously WHO grade I, remain as a tumor type in the new classification system; however, they are now considered grade II tumors since they have similar recurrence to conventional spinal ependymomas [3].

MPEs are most commonly located in the lumbar spine (52.9%) and lumbosacral spine (23.5%), mainly in the regions of the conus medullaris and cauda equina, and very rarely in the cerebral ventricles and the brain [6, 7]. They are slow-growing tumors with a long clinical course. The duration of symptoms before clinical diagnosis ranges from 1 month to 6 years [6, 23]. The most common clinical symptoms of SME include pain, weakness, numbness in the extremities and less commonly sphincter dysfunction, urinary incontinence, saddle hypoesthesia and sexual dysfunction [6]. As the tumor progresses to involve the nerve roots patients may develop intractable lumbosacral and/or lower extremity pain, and even flaccid paralysis in later stages of disease progression [5].

Consensus remains that GTR offers the best outcomes for SME, with a lower risk for recurrence and metastasis compared to subtotal resection (STR). Incomplete resection is significantly associated with tumor recurrence, with data suggesting recurrence in up to 30% of patients undergoing STR over an average of 41.5 months versus no recurrence in those who underwent GTR [6].

Furthermore complicating postoperative predictions, there is an association between piecemeal resection with the capsular violation and tumor recurrence [24]. In these situations, adjuvant radiotherapy after capsular violation improves PFS. However, even with GTR, recurrence rates may reach up to 15% in the setting of capsular violation, and 45% following STR [24].

The role of radiotherapy in SME is still debated. Recent evidence supports the use of radiotherapy for recurrence as it has been shown to improve PFS [6, 9, 24,25,26]. However, controversy exists and in a recent retrospective study, adjuvant radiotherapy after both GTR and STR did not improve recurrence-free survival (RFS) [27]. In a SEER database analysis, the cause-specific survival (CSS) in the youngest group of patients treated with complete surgical resection and radiation therapy was similar to surgery alone [28]. In most reported studies, focal radiation therapy to a dose of 50.4–54 Gy has been used with acceptable morbidity. Cranio-spinal radiation therapy with its associated acute and delayed morbidity is generally reserved only for cases with diffuse leptomeningeal disease [26]. The most recent National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines (Version 2.2021) suggest that post-operative spine MRI, as well as CSF analysis should be used to determine the need for adjuvant radiation in adult spinal myxopapillary ependymomas. Adjuvant radiation is not recommended after en-bloc resection without capsule violation and negative CSF cytology. Guidelines recommend focal radiation in the case of GTR with capsule violation and negative cytology or STR with negative cytology; craniospinal radiation is recommended in the case of GTR or STR with cranial or spinal metastasis or positive CSF cytology. CSF analysis is indicated for clinical concern of meningeal dissemination and should be performed 2 weeks after post-operative MRI to decrease the risk of false imaging results and cytology results [29].

Despite their propensity for recurrence, a predilection for craniospinal dissemination, even after GTR, further complicates the management of SME. Data suggests that recurrence still ranges from 10-20% over the span of up to forty years [2, 13]. Following STR, recurrence rates are worse and have been reported from to 23.4–32.6% in adults. Interestingly, recurrence in the pediatric population approaches 40.5% and it is hypothesized that pediatric SMEs may represent more aggressive tumors with higher propensity for a multifocal presentation [7]. Recurrence may be local or distant via drop metastases disseminated through CSF to the entirety of the neuroaxis. In a retrospective study by Kraetzig et al., local recurrence was found in 26.3% of patients after a median 36-month follow-up and distant metastases were found in 57.9% of 19 patients, with only 4 of them presenting with distal metastases at initial diagnosis [13].

Interestingly, in adults, the presentation of SME with multiple lesions at the time of diagnosis is uncommon and there have been only 14 cases described (Table 1). Progressive lower back pain over the span of 2-3 months is the most common clinical presentation of multifocal SME and most cases have resolution of symptoms with no active disease on short-term follow-up after resection (Table 2). Limited to case reports and small series, data from immunohistochemical analyses of these tumors has failed to demonstrate patterns that may explain the multifocal presentation in these patients and molecular characterization of tumors associated with this rare event don’t exist. Some studies suggest that certain markers such as EGFR or the activity of MIB 2 can predict the aggressiveness and likelihood of recurrence in MPE, but there is still a paucity of data [30, 31].

The best practice for multifocal SMEs is extrapolated from evidence based on solitary lesions, which includes GTR and adjuvant radiotherapy if GTR is not possible. In the case of multiple lesions at diagnosis, a staged approach to resection is reasonable if it can facilitate safe maximal resection. However, given drop metastases at initial presentation, the likelihood of recurrence is likely higher in this patient population even in the setting of a radiographic GTR. As a result, we favor early radiation treatment. However, further evidence is necessary to assess the role of craniospinal vs. local-regional radiotherapy for the treatment of these rare occurrences.

Despite a high rate of recurrence and metastasis, the prognosis for SMEs remains positive as 90% of patients reported favorable outcomes at final follow-up, without neurologic deficits or only with mild pain or sensory/motors deficits that did not impact daily life. The 10-year overall survival rate is around 92%- and 10-year progression-free survival remains 61% for those undergoing surgical treatment, regardless of the extent of resection [32, 33]. However, longer-term prognosis is unclear due to their long clinical course and lack of studies with sufficient follow-up.

Conclusion

Spinal myxopapillary ependymomas (SME) are rare WHO grade II neoplasms of the spinal cord. Despite their good prognosis, they have a high propensity for metastasis and recurrence. The presentation of SME as multifocal is uncommon, especially in the adult population. According to current literature, GTR offers the best progression-free survival (PFS) and outcomes for SME. In cases where GTR cannot be achieved, adjuvant radiotherapy is suggested to improve PFS and lead to lower rates of recurrence. Therefore, a staged approach for the multifocal disease is reasonable to achieve maximal resection and early radiotherapy should be considered in these cases due to CSF dissemination. However, further evidence is necessary to assess the role of craniospinal vs. local-regional radiotherapy for the treatment of these rare occurrences.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Ruda R. EANO guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of ependymal tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20:445–56.

Sonneland PR, Scheithauer BW, Onofrio BM. Myxopapillary ependymoma. A clinicopathologic and immunocytochemical study of 77 cases. Cancer. 1985;56:883–93.

Louis DN. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23:1231–51.

Gagliardi FM. Ependymomas of the filum terminale in childhood: report of four cases and review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 1993;9:3–6.

Verstegen MJ, Bosch DA, Troost D. Treatment of ependymomas. Clinical and non-clinical factors influencing prognosis: a review. Br J Neurosurg. 1997;11:542–53.

Liu T. Clinical characteristics and surgical outcomes of spinal myxopapillary ependymomas. Neurosurg Rev. 2020;43:1351–6.

Feldman WB. Tumor control after surgery for spinal myxopapillary ependymomas: distinct outcomes in adults versus children: a systematic review. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;19:471–6.

Jahanbakhshi A. Adjunctive treatment of myxopapillary ependymoma. Oncol Rev. 2021;15:518.

Pica A. The results of surgery, with or without radiotherapy, for primary spinal myxopapillary ependymoma: a retrospective study from the rare cancer network. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:1114–20.

Rege SV. Spinal myxopapillary ependymoma with interval drop metastasis presenting as cauda equina syndrome: case report and review of literature. J Spine Surg. 2016;2:216–21.

Fujiwara Y. Remarkable efficacy of temozolomide for relapsed spinal myxopapillary ependymoma with multiple recurrence and cerebrospinal dissemination: a case report and literature review. Eur Spine J. 2018;27:421–5.

Bates JE. Spinal drop metastasis in myxopapillary ependymoma: a case report and a review of treatment options. Rare Tumors. 2014;6:5404.

Kraetzig T. Metastases of spinal myxopapillary ependymoma: unique characteristics and clinical management. J Neurosurg Spine. 2018;28:201–8.

Straus D. Disseminated spinal myxopapillary ependymoma in an adult at initial presentation: a case report and review of the literature. Br J Neurosurg. 2014;28:691–3.

Toktas ZO. Disseminated adult spinal extramedullary myxopapillary ependymoma. Spine J. 2015;15:e69–70.

Khan NR. Primary Seeding of Myxopapillary Ependymoma: Different Disease in Adult Population? Case Report and Review of Literature. World Neurosurg. 2017;99:812 e21–812.e26.

Andoh H. Multi-focal Myxopapillary Ependymoma in the Lumbar and Sacral Regions Requiring Cranio-spinal Radiation Therapy: A Case Report. Asian Spine J. 2011;5:68–72.

Landriel F. Multicentric extramedullary myxopapillary ependymomas: Two case reports and literature review. Surg Neurol Int. 2012;3:102.

McLaughlin N, Guiot MC, Jacques L. Double myxopapillary ependymomas of the filum terminale. Can J Neurol Sci. 2011;38:151–4.

Yener U. Concomitant Double Tumors of Myxopapillary Ependymoma Presented at Cauda Equina-Filum Terminale in Adult Patient. Korean J Spine. 2016;13:33–6.

Ogul H. Multiple spinal myxopapillary ependymomas presented with back pain. Spine J. 2015;15:e3–4.

Omerhodzic I. Myxopapillary Ependymoma of the Spinal Cord in Adults: A Report of Personal Series and Review of Literature. Acta Clin Croat. 2020;59:329–37.

Chan MD, McMullen KP. Multidisciplinary management of intracranial ependymoma. Curr Probl Cancer. 2012;36:6–19.

Abdulaziz M. Outcomes following myxopapillary ependymoma resection: the importance of capsule integrity. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;39:E8.

Akyurek S. Spinal myxopapillary ependymoma outcomes in patients treated with surgery and radiotherapy at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. J Neurooncol. 2006;80:177–83.

Chao ST. The role of adjuvant radiation therapy in the treatment of spinal myxopapillary ependymomas. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011;14:59–64.

Kotecha, R. Analyzing the role of adjuvant or salvage radiotherapy for spinal myxopapillary ependymomas. J Neurosurg Spine. 2020;11:1–6.

Edson M, Paulino AC. Treatment Trends and Outcomes by Age in Myxopapillary Ependymoma of the Spine. Int J Radiat Oncol, Biol, Phys. 2012;84:S281.

Network, NCC Central Nervous System Cancers (Version 2.2021). March 28, 2022]; Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cns.pdf.

Verma A. EGFR as a predictor of relapse in myxopapillary ependymoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59:746–8.

Prayson RA. Myxopapillary ependymomas: a clinicopathologic study of 14 cases including MIB-1 and p53 immunoreactivity. Mod Pathol. 1997;10:304–10.

Reni M. Ependymoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;63:81–9.

Weber DC. Long-term outcome of patients with spinal myxopapillary ependymoma: treatment results from the MD Anderson Cancer Center and institutions from the Rare Cancer Network. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17:588–95.

Acknowledgements

This work received no specific grant from any funding agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors of this manuscript have contributed to, read, and approved of the manuscript and its submission for publication. The authors will be happy to provide the required forms should the manuscript be accepted for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

I, Randy S. D’Amico, certify that this manuscript is a unique submission and has not been previously published elsewhere, nor is it under consideration for publication, in part or in full, with any other source in any medium.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Patient information was de-identified and informed consent obtained.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tabor, J.K., Ryu, B., Schneider, D. et al. Multifocal lumbar myxopapillary ependymoma presenting with drop metastasis: a case report and review of the literature. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 8, 43 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-022-00513-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-022-00513-x

This article is cited by

-

Clinical management and prognosis of spinal myxopapillary ependymoma: a single-institution cohort of 72 patients

European Spine Journal (2023)