Abstract

Study design

Cross-sectional study.

Objective

To identify predictors of quality of life (QoL) among family caregivers of people with spinal cord injuries (SCI), considering caregiver and care recipient characteristics, and to evaluate the predictive value of caregiver burden (CB) on the QoL of family caregivers.

Setting

Multicenter study in four spinal units across Italy.

Methods

Secondary analysis of the data obtained during the validation of the Italian version of the Caregiver Burden Inventory in Spinal Cord Injuries (CBI-SCI) questionnaire. In all, 176 family caregivers completed a socio-demographic questionnaire, the Short Form-36, the CBI-SCI, and the Modified Barthel Index. A first linear regression analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of each domain of caregiver QoL. A second linear regression analysis including CBI-SCI was then performed to evaluate the predictive value of CB on caregiver QoL.

Results

Participants reported reduced physical and mental QoL. Significant predictors of lower scores in physical dimensions of QoL were older age and female gender. Contextual factors following SCI, such as economic difficulties and the presence of a formal caregiver, significantly predicted emotional QoL in family caregivers. Identified predictors explained 13–32% of variance. CB was a significant predictor (p < 0.001) when added to all proposed models, increasing the explained variance from 7 to 26%.

Conclusion

Neither the clinical characteristics of, nor the relationship with care recipients predicted a worse caregiver QoL, whereas the CB did. The CB was a strong predictor of QoL among family caregivers and should be kept to a minimum to promote caregiver well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In recent decades, family caregivers of people with spinal cord injury (SCI) have received increasing attention due to their crucial responsibilities. Indeed, after their stay in a rehabilitation center, the majority of people with SCI are discharged, and once home, their family members are often pressured to take on the role of caregiver for social and economic reasons [1]. These family caregivers help maintain the physical and emotional well-being of their care recipients [2], and many people with SCI have claimed that family caregivers are their only source of support after rehabilitation [3, 4].

The perceived lack of preparation for assuming the complex role of family caregiver often leads to stress and discomfort [5, 6], which can contribute to a significant decrease in quality of life (QoL) [3]. Longitudinal studies conducted in caregivers of people with SCI showed a change in the QoL of family caregivers after rehabilitation [7, 8]. Domains related to the mental QoL of family caregivers were the most affected in the early stages after SCI [8]. Moreover, as family caregivers themselves often suffer from chronic illnesses [9], they showed a decline in long-term physical functioning, which was related to age and duration of caregiving [10]. To date, few studies have focused on the factors that influence QoL in family caregivers of people with SCI [3, 10]. The characteristics of caregivers [9, 10] and their care recipients [3, 4] could be pivotal factors in predicting the QoL of family caregivers. Although identifying predictors of caregiver QoL represents an opportunity to prevent negative consequences in family caregivers and SCI survivors [5], the majority of studies so far have been correlational and examined this construct in relation to socio-demographic and disease-related characteristics [9, 11]. The physical effort required to assist SCI survivors in their activities of daily living [11], combined with increased costs and limited welfare resources, subject families to psychological distress, reduced social participation, and significant burden [1].

Caregiver burden (CB) is generally defined as a multidimensional phenomenon that influences the physical, mental, and social aspects of daily life [12]; it is widely used to indicate the burden that caregivers perceive to be attributable to their widespread responsibilities [12, 13]. CB is frequently associated with mental trauma, especially among family caregivers, as they often experience psychological distress that is similar to that of their family members with SCI [14]. Furthermore, previous reports have shown that perceived CB did not decrease after SCI rehabilitation [7] and demonstrated negative correlations with all aspects of QoL, especially those related to social functioning [15].

CB has been already used as a predictor of QoL in family caregivers of patients with different neurological disorders [16,17,18], and results have highlighted the modifying effect of this burden and emphasized the need to control distress among relatives from the earliest stages of the disorder [19]. However, the predictive value of CB on the QoL of family caregivers of people with SCI has not yet been studied. Dissatisfaction among family caregivers and a high CB may negatively affect the well-being of care recipients with SCI [20]. At present, studies on CB in family caregivers of people with SCI have only evaluated the relationship with QoL on a correlation level [3, 15]. A better understanding of the role that CB plays in caregiver QoL could be useful to healthcare professionals, as it might allow them to identify distressed caregivers earlier and help them to design specific interventions aimed at predicting and improving the trajectory of QoL. Thus, the aim of this study was to identify predictors of QoL among family caregivers of people with SCI, considering caregiver and care recipient characteristics, and to evaluate the predictive value of CB on the QoL of family caregivers.

Methods

Design and sample

This study provides a secondary analysis of data obtained during the validation of the Italian version of the Caregiver Burden Inventory in Spinal Cord Injuries (CBI-SCI) questionnaire [21]. A consecutive sample of family caregivers was enrolled during periodic follow-up appointments at the outpatient clinics of four spinal units across Italy. To be included, the caregiver had to be a family member of an individual with traumatic or nontraumatic SCI who had been discharged at least 6 months ago, be aged 18 or older, and speak Italian. Formal, paid caregivers, and caregivers with cognitive disorders were excluded.

Instruments

The full study procedure was described in the parent study [21]. Briefly, eligible family caregivers were asked to complete a set of structured questionnaires requiring about 15 min. All administered questionnaires have been validated and used in the SCI context, and showed excellent psychometric properties [9, 21, 22].

The QoL of family caregivers was measured using the Italian version of the Short Form-36 (SF-36) [23]. This questionnaire is composed of 36 items covering eight domains (physical functioning, bodily pain, role-physical, general health, social functioning, role-emotional, mental health, and vitality), with the score for each domain ranging from 0 (worst possible QoL) to 100 (best possible QoL). CB was assessed using the Italian version of the CBI-SCI [21], a 24-item, self-administered questionnaire that measures the extent of the perceived burden on five different domains: time-dependent burden, developmental burden, physical burden, social burden, and emotional burden. The total score of the CBI-SCI ranges from 0 (absence of burden) to 100 (highest obtainable burden level). The functional independence of care recipients with SCI was assessed by the caregiver, using the Modified Barthel Index (MBI) [24]. This mono-dimensional scale consists of ten items that describe the functioning of SCI survivors in activities of daily living, with a total score ranging from 0 (total dependence) to 100 (independence).

Socio-demographic data, including age, gender, marital status, family composition, level of education, employment, residence (urban/suburban), relationship, and cohabitation status, were collected for both family caregivers and individuals with SCI. Caregivers were also asked to provide information about the duration of caregiving (<2 years/≥2 years), and the presence of a formal, paid caregiver, or respite care during the last 3 months. Two specific questions investigated the economic status of family caregivers, particularly the perceived worsening of, or improvement in, that status in the last year. Clinical characteristics of care recipients were provided by family caregivers and covered level of injury, etiology, and time since injury (<2 years/≥2 years).

Data analysis

Categorical variables were computed as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables are expressed as averages and standard deviations, or as median and interquartile ranges, for normally and non-normally distributed variables, respectively. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was applied to test the normality of the distribution.

The MBI score and age were divided into three categories; all other independent variables that were not dichotomic were dichotomized. Due to non-normally distributed data, univariate non-parametrical tests were performed to identify any significant differences between independent variables and the eight domains of the SF-36. In particular, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied for dichotomic data, and the Kruskal–Wallis test by ranks was performed for MBI score and age.

Variables that had statistically significant results in the univariate analysis (Supplementary Table 1) were included in a first multivariable linear regression analysis to identify independent predictors of each of the eight domains of the SF-36 among family caregivers of people with SCI (Model 1). A second linear regression analysis including CBI-SCI score was then performed for each of the eight SF-36 domains to evaluate the predictive value of CB on caregiver QoL (Model 2). No multicollinearity issues were found (variance inflation factor < 5 and tolerance test > 0.20). To test the hypothesis that CB would explain a considerable amount of variance in the QoL of family caregivers of people with SCI, the coefficient of determination (r2) was calculated to assess the portion of change explained by the addition of the CBI-SCI total score to each of the eight domains of the SF-36. Considering the high number of predictors included in the various models, a sample size of 146 subjects was deemed sufficient [25]. All tests were two sided, and statistical significance was set at α = 0.05. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

A total of 176 family caregivers were recruited: 146 were females (83%), 139 (79%) were living with the care recipient, and 95 (54%) had a duration of caregiving of more than 3 years. Ninety-four (54%) family caregivers were partners of their care recipients, and 59 (33%) were unemployed. Among the care recipients with SCI, 87 (49%) were paraplegic, 89 (51%) were tetraplegics, and 61 (35%) were active workers (Table 1). The majority of care recipients were totally or severely dependent on caregivers (n = 111, 64%).

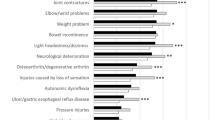

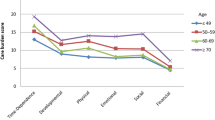

Role-physical and role-emotional were the SF-36 domains that showed the lowest scores, while physical and social functioning showed the highest scores. The CBI-SCI domains that received the highest scores were time-dependent burden and physical burden, whereas emotional burden had the lowest scores (Table 2).

Predictors of reduced physical functioning were the family caregiver characteristics older age and female gender, and the care recipient characteristic age under 25 years old. These predictors explained 26% of the variance in physical functioning. When added to the model, CB was a significant predictor of decline in this domain (β = −0.28, p < 0.001); conversely, the presence of older adults in the household was a significant predictor of increased physical functioning (β = 0.16, p = 0.02). The second model increased the explained variance of this domain to 33%. Female gender in family caregivers was a predictor of improved bodily pain, as was cohabitation with the care recipient, and caregiver’s age of 50–70 years. This first model explained 19% of the total variance in this domain. Adding CB in the second model (β = −0.41, p < 0.001) increased the explained variance by 14%, and both CB and caregiver’s age of 50–70 years (β = −0.18, p = 0.04) were identified as reliable predictors of bodily pain. Lower scores for role-physical were significantly associated with perceived economic difficulties and caregiver age over 70 years, which explained 14% of the total variance in this domain. When CB was added to the model, it became another significant predictor (β = −0.47, p < 0.001), increasing the total explained variance by 21%. Predictors of decreased general health were caregiver age of 50–70 years and caregiver age over 70 years. This first model explained the 17% of the total variance in this domain, and adding CB (β = −0.44, p < 0.001) increased the explained variance to 35% (Table 3).

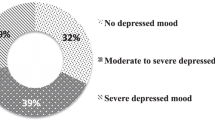

Lower scores in the social functioning domain were significantly associated with perceived economic difficulties and care recipient’s marital status. In contrast, male caregivers, the presence of a formal, paid caregiver, and the care recipient having been injured more than 2 years ago, predicted higher performances in this domain. These predictors explained 18% of the variance in social functioning; when CB was added to this model (β = −0.53, p < 0.001) this number increased to 26%, but caregiver gender and care recipient’s marital status became nonsignificant predictors. Perceived economic difficulties and care recipient’s total dependency were associated with a decrease in scores for the role-emotional domain, while the presence of a formal caregiver was associated with an improvement in this domain, explaining the 13% of the total variance. When CB was added to the model, it became an influential predictor (β = −0.45, p < 0.001); the presence of formal caregiving (β = 0.13, p = 0.05) in this model increased the explained variance to 30%. Predictors of reduced mental health were perceived economic difficulties, care recipient’s marital status, and care recipient’s employment. In contrast, perceived financial improvement, presence of a formal caregiver, and the care recipient having been injured more than 2 years ago were associated with better scores in this domain. The first model explained 32% of the variance in mental health, and, although care recipient’s employment became a nonsignificant predictor, CB was identified as a reliable predictor of a lower score in the mental health domain (β = −0.46, p < 0.001), increasing the total explained variance by 20%. Improvement in vitality was associated with caregiver male gender and perceived financial improvement. In contrast, caregiver age of 50–70 years, caregiver age over 70 years, and care recipient’s marital status were responsible for a decrease in this domain. These variables explained 19% of the total variance. When added to the model, CB was an influential predictor of decline in this domain (β = −0.36, p < 0.001), along with caregiver age of 50–70 years (β = −0.27, p = 0.007), caregiver age over 70 years (β = −0.18, p = 0.037), and care recipient’s marital status (β = −0.19, p = 0.006). Perceived financial improvement was associated with an increase in vitality (β = 0.18, p = 0.01), and this second model explained 30% of the total variance (Table 4).

Discussion

This study identified predictors of specific domains of QoL in family caregivers of people with SCI. Family caregivers reported reduced physical and mental QoL, with scores that were significantly lower than those reported in the general Italian population [23], emphasizing the considerable impact SCI has on family caregivers [10, 11]. In fact, family caregivers of SCI survivors experience frequent physical distress, sleep disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and obesity [26]. Moreover, findings from this study highlighted that all the domains of the SF-36 had different predictors, suggesting that the personal characteristics of caregivers predict physical QoL, whereas the characteristics related to the adjustment after SCI are more reliable predictors of mental QoL. Previous literature has shown the correlation of older age and female gender with decreased scores in physical dimensions of caregiver QoL [9, 10], and these variables are already considered significant predictors of reduced physical QoL in caregivers of people with multiple sclerosis [27]. Moreover, physical QoL was shown to be lower than mental QoL in caregivers of individuals with paraplegia [3], highlighting the substantial physical nature of caregiving. The trajectory of adaptation of caregivers implies a high level of psychological distress during rehabilitation, which decreases gradually after hospital discharge and provokes a consequent rebound in mental QoL [7, 8]. This is consistent with the findings of the current study, which highlight the predictive value of time since the care recipient’s injury on SF-36 scores for mental domains. Social and emotional aspects of prolonged assistance influence the well-being of caregivers of individuals with severe disabilities [28, 29]. In this sense, the predictive value of economic status on the mental dimensions of QoL in this study might confirm that psychological distress and depression are more frequent in caregivers with a reduced income [30]. Moreover, the presence of a formal caregiver improved the mental QoL of the current study participants, suggesting that paid assistance may relieve families of some of the distress that may arise from their care duties [30].

The findings of this study seem to indicate that caregiver characteristics and contextual factors strongly predict caregiver QoL, and that, in contrast, care recipient characteristics do not predict caregiver well-being. Several studies have confirmed the independence between caregiver QoL and clinical characteristics of care recipients with neurological disorders [17], including SCI [11]. The marital status of care recipients predicted lower scores in the domains of mental health and vitality, confirming that SCI also causes distress in caregivers, who are subjected to a deterioration of their spousal relationship leading to high divorce rates [31]. Furthermore, although previous studies have mostly examined spouses [2, 10], we found no significant differences in results by caregiver’s relationship to the SCI survivor. Hence, the findings of the current study seem to suggest that caregivers of individuals with SCI perceived a lower QoL regardless of the clinical characteristics of their care recipients or their relationship to them. Future studies should further investigate factors that may influence caregiver QoL, such as the impact of the relationship with care recipients on CB, the presence of older adults acting as additional care recipients in the household, and the caregiver’s role in supporting the reintegration of younger SCI survivors into society.

The findings of this study show the crucial predictive value of perceived CB on caregiver QoL and integrate the previously reported correlation of CB with the well-being of caregivers of people with SCI [15, 32], highlighting the predictive value of this variable, which improved the amount of total explained variance in all SF-36 domains. Previous studies found a strong association between perceived CB and poorer scores in the domains of general health, bodily pain [33], social functioning, and mental health [15], corroborating the multidimensional nature of this phenomenon. Moreover, the predictive role of CB on QoL has already been highlighted in caregivers of patients with stroke [17], dementia [18], and neurocognitive disorders [16]. However, as CB is a nonclinical predictor of QoL, it may not be given the same importance as clinical or socio-demographic variables; thus healthcare professionals may choose not to collect this information, or they may consider it a consequence of cultural or social aspects. The current study findings seem to support the adoption of CB as a predictor of QoL in caregivers of people with SCI and suggest that targeted monitoring systems should be implemented to protect families from potential social or health issues over time. Given the progressive improvement in mental QoL [7, 8], and the stability of CB over time [7, 34], specific interventions that reduce the burden of family caregivers of SCI survivors should be designed and assessed to enhance and accelerate the improvement of their well-being. Interventions that provide education and standardized information through problem-solving training [35, 36], psycho-educational interventions [37], computer/telephone technology [38], and support groups [39] have been reported to be the most helpful in improving caregiver QoL, especially if the care recipient was involved. The adaptation of these interventions to reduce CB may constitute a resource for healthcare professionals in promoting the trajectory of adaptation after SCI. Consistent with other studies, emotional burden was the domain with the lowest score reported by participants [15, 40, 41]. In contrast, the CBI-SCI explained a high amount of variance in the models on the mental dimensions of the SF-36, suggesting that there is an opportunity to further investigate whether CB is indicative of emotional distress in future studies. Additional studies are also required to identify predictors of CB and to determine the feasibility of adding these variables as another measure of QoL. Such studies would enhance the knowledge of these phenomena, and provide practical recommendations to healthcare professionals.

Although this study represents the first exploration of predictors of caregiver QoL and the contribution of perceived CB in family caregivers of people with SCI, it has several limitations. The specific area in which the study was conducted, combined with the use of a cross-sectional design and recruitment during routine follow-up appointments, might limit the generalizability of results. Nevertheless, the characteristics of the recruited caregivers, as well as those of the SCI survivors, are comparable to available epidemiological data. Furthermore, although information was collected on several variables, the effect of comorbidities or secondary conditions among caregivers or care recipients was not examined [41], suggesting the need to conduct further studies to deepen the understanding of the influence of these aspects on the adjustment process following SCI.

Conclusion

This study contributes to the understanding of caregiving after SCI. Caregiver characteristics, such as older age and female gender, are significant predictors of physical QoL among family caregivers. Conversely, contextual factors following SCI, such as changes in economic situation, the presence of a formal caregiver, and the care recipient’s time since SCI, predict mental domains of QoL among family caregivers. The obtained results may suggest that the simple acknowledgment of their caregiving role leads family caregivers of people with SCI to assign a lower rating to their QoL. Beyond the aforementioned variables, CB proved to be a strong predictor of QoL in family caregivers of people with SCI. Therefore, as reducing this perceived burden could help promote caregiver QoL, health policies might focus on preventive strategies and interventions that target caregivers with the identified characteristics to offer health, economic, and social support.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Lynch J, Cahalan R. The impact of spinal cord injury on the quality of life of primary family caregivers: a literature review. Spinal Cord. 2017;55:964–78.

Post MWM, Bloemen J, Witte LPde. Burden of support for partners of persons with spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord. 2005;43:311–9.

Blanes L, Carmagnani MIS, Ferreira LM. Health-related quality of life of primary caregivers of persons with paraplegia. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:399–403.

Samsa GP, Hoenig H, Branch LG. Relationship between self-reported disability and caregiver hours. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;80:674–84.

Glozman JM. Quality of life of caregivers. Neuropsychol Rev. 2004;14:183–96.

Visser-Meily A, van Heugten C, Post M, Schepers V, Lindeman E. Intervention studies for caregivers of stroke survivors: a critical review. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56:257–67.

Middleton JW, Simpson GK, De Wolf A, Quirk R, Descallar J, Cameron ID. Psychological distress, quality of life, and burden in caregivers during community reintegration after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95:1312–9.

Backx APM, Spooren AIF, Bongers-Janssen HMH, Bouwsema H. Quality of life, burden and satisfaction with care in caregivers of patients with a spinal cord injury during and after rehabilitation. Spinal Cord. 2018;56:890–9.

Nogueira PC, Rabeh SAN, Caliri MHL, Dantas RAS. Health-related quality of life among caregivers of individuals with spinal cord injury. J Neurosci Nurs. 2016;48:28–34.

Ebrahimzadeh MH, Shojaei B-S, Golhasani-Keshtan F, Soltani-Moghaddas SH, Fattahi AS, Mazloumi SM. Quality of life and the related factors in spouses of veterans with chronic spinal cord injury. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:48.

Ünalan H, Gençosmanoğlu B, Akgün K, Karamehmetoğlu Ş, Tuna H, Önes K, et al. Quality of life of primary caregivers of spinal cord injury survivors living in the community: controlled study with Short Form-36 questionnaire. Spinal Cord. 2001;39:318–22.

Gillick MR. The critical role of caregivers in achieving patient-centered care. JAMA. 2013;310:575–6.

Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS. Caregiver burden: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311:1052–60.

Budh CN, Österåker A-L. Life satisfaction in individuals with a spinal cord injury and pain. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21:89–96.

Maitan P, Frigerio S, Conti A, Clari M, Vellone E, Alvaro R. The effect of the burden of caregiving for people with spinal cord injury (SCI): a cross-sectional study. Ann Ist Super Sanità. 2018;54:185–93.

Young DK, Ng PY, Kwok T. Predictors of the health-related quality of life of Chinese people with major neurocognitive disorders and their caregivers: the roles of self-esteem and caregiver’s burden. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17:2319–28.

Jeong Y-G, Myong J-P, Koo J-W. The modifying role of caregiver burden on predictors of quality of life of caregivers of hospitalized chronic stroke patients. Disabil Health J. 2015;8:619–25.

Abdollahpour I, Nedjat S, Salimi Y, Noroozian M, Majdzadeh R. Which variable is the strongest adjusted predictor of quality of life in caregivers of patients with dementia? Psychogeriatrics. 2015;15:51–7.

Corallo F, Cola MCD, Buono VL, Lorenzo GD, Bramanti P, Marino S. Observational study of quality of life of Parkinson’s patients and their caregivers. Psychogeriatrics. 2017;17:97–102.

Charlifue SB, Botticello A, Kolakowsky-Hayner SA, Richards JS, Tulsky DS. Family caregivers of individuals with spinal cord injury: exploring the stresses and benefits. Spinal Cord. 2016;54:732–6.

Conti A, Clari M, Garrino L, Maitan P, Scivoletto G, Cavallaro L, et al. Adaptation and validation of the Caregiver Burden Inventory in Spinal Cord Injuries (CBI-SCI). Spinal Cord. 2019;57:75–82.

Küçükdeveci AA, Yavuzer G, Tennant A, Süldür N, Sonel B, Arasil T. Adaptation of the Modified Barthel Index for use in physical medicine and rehabilitation in Turkey. Scand J Rehabil Med. 2000;32:87–92.

Apolone G, Mosconi P. The Italian SF-36 Health Survey: translation, validation and norming. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1025–36.

Galeoto G, Lauta A, Palumbo A, Castiglia S, Mollica R, Santilli V, et al. The Barthel index: italian translation, adaptation and validation. Int J Neurol Neurother. 2015;2:1–7.

Wilson Van Voorhis CR, Morgan BL. Understanding power and rules of thumb for determining sample sizes. Tutor Quant Methods Psychol. 2007;3:43–50.

LaVela SL, Landers K, Etingen B, Karalius VP, Miskevics S. Factors related to caregiving for individuals with spinal cord injury compared to caregiving for individuals with other neurologic conditions. J Spinal Cord Med. 2015;38:505–14.

Patti F, Amato MP, Battaglia MA, Pitaro M, Russo P, Solaro C, et al. Caregiver quality of life in multiple sclerosis: a multicentre Italian study. Mult Scler. 2007;13:412–9.

Mitchell LA, Hirdes J, Poss JW, Slegers-Boyd C, Caldarelli H, Martin L. Informal caregivers of clients with neurological conditions: profiles, patterns and risk factors for distress from a home care prevalence study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:350.

Carlozzi NE, Kratz AL, Sander A, Chiaravalloti ND, Brickell T, Lange R, et al. Health-related quality of life in caregivers of individuals with traumatic brain injury: development of a conceptual model. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:105–13.

Kim D. Relationships between caregiving stress, depression, and self-esteem in family caregivers of adults with a disability. Occup Ther Int. 2017;2017:1686143.

Kreuter M. Spinal cord injury and partner relationships. Spinal Cord. 2000;38:2–6.

Nogueira PC, Rabeh SAN, Caliri MHL, Dantas RAS, Haas VJ. Burden of care and its impact on health-related quality of life of caregivers of individuals with spinal cord injury. Rev Lat Am Enferm. 2012;20:1048–56.

Fekete C, Tough H, Siegrist J, Brinkhof MW. Health impact of objective burden, subjective burden and positive aspects of caregiving: an observational study among caregivers in Switzerland. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e017369.

van Exel NJA, Koopmanschap MA, van den Berg B, Brouwer WBF, van den Bos GaM. Burden of informal caregiving for stroke patients. Identification of caregivers at risk of adverse health effects. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;19:11–7.

Elliott TR, Berry JW. Brief problem-solving training for family caregivers of persons with recent-onset spinal cord injuries: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65:406–22.

Elliott TR, Brossart D, Berry JW, Fine PR. Problem-solving training via videoconferencing for family caregivers of persons with spinal cord injuries: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46:1220–9.

Molazem Z, Falahati T, Jahanbin I, Jafari P, Ghadakpour S. The effect of psycho-educational interventions on the quality of life of the family caregivers of the patients with spinal cord injury: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2014;2:31–9.

Schulz R, Czaja SJ, Lustig A, Zdaniuk B, Martire LM, Perdomo D. Improving the quality of life of caregivers of persons with spinal cord injury: a randomized controlled trial. Rehabil Psychol. 2009;54:1–15.

Sheija A, Manigandan C. Efficacy of support groups for spouses of patients with spinal cord injury and its impact on their quality of life. Int J Rehabil Res. 2005;28:379–83.

Gajraj-Singh P. Psychological impact and the burden of caregiving for persons with spinal cord injury (SCI) living in the community in Fiji. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:928–34.

Conti A, Clari M, Nolan M, Wallace E, Tommasini M, Mozzone S, et al. The relationship between psychological and physical secondary conditions and family caregiver burden in spinal cord injury: a correlational study. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2019;25:271–80.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the participants and the staff at the Spinal Cord Injury Units of Città della Salute e della Scienza Hospital of Torino, IRCCS Fondazione Santa Lucia of Roma, Cannizzaro Hospital of Catania, and Careggi Hospital of Firenze for dedicating their time to this study.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AC and MC were responsible for designing and writing the study protocol, and for submitting the study to the ethical committee. AC was also responsible for writing the report and coordinating the recruitment centers. AC and MC interpreted the results. FR was responsible for the database managing, analyzing data, and interpreting results. He contributed to writing the report. GS, MC, and SC were responsible for recruiting the participants and managing the data. They provided feedback on the report. SC also provided feedback on the report.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was approved (Resolution No. 1002/2016 - #CS/1040) by the Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino, Mauriziano Hospital, ASL TO 1 Research Ethics Committee. All recruitment centers gave their authorization to participate in the study. In addition, all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed.

Informed consent

All participants provided written, informed consent, and anonymity was maintained throughout the research process.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Conti, A., Ricceri, F., Scivoletto, G. et al. Is caregiver quality of life predicted by their perceived burden? A cross-sectional study of family caregivers of people with spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord 59, 185–192 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-0528-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-0528-1

This article is cited by

-

Self-Efficacy and Psychological Well-Being of Family Caregivers of Persons with Spinal Cord Injury

Psychological Studies (2022)