Abstract

Study design

Cohort study.

Objective

To determine the prevalence and to identify predictors of prescription opioid use among persons with nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction within 1 year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation.

Setting

Ontario, Canada.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using administrative data to determine predictors of receiving prescription opioids during the 1 year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation among persons with nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction between April 1, 2004 and March 31, 2015. We modeled the outcome using a Poisson multivariable regression and reported relative risks with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

We identified 3468 individuals with nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction (50% male) with 67% who were aged ≥66. Over half of the cohort (60%) received opioids during the observation period. Older adults (≥66 years old) were significantly more likely to experience comorbidities (p < 0.05) but less likely to be dispensed opioids following rehabilitation discharge. Being female, previous opioid use before rehabilitation, experiencing lower continuity of care, increasing comorbidity level, low functional status, and having a previous diagnosis of osteoarthritis or mental illness were significant risk factors for receiving opioids after discharge, as shown in a multivariable analysis. Increasing length of rehabilitation stay and higher income were protective against opioid receipt after discharge.

Conclusion

Many individuals with nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction in Ontario are prescribed opioids after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. This may be problematic due to the number of severe complications that may arise from opioid use and their use in this population warrants future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pain is highly prevalent among individuals living with spinal cord injury (both traumatic and nontraumatic) [1] and is typically managed using a combination of pharmacotherapy (e.g., prescription opioids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and antidepressants) and non-pharmacological methods (e.g., physical therapy, psychotherapy, and occupational therapy) [2, 3]. As with many populations experiencing pain, one pharmacotherapy option is the prescription of opioids. However, opioid use can result in a number of adverse events [4,5,6], which may be particularly taxing for individuals with nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction due to the complexity of their comorbidities. Unlike traumatic spinal cord injury where an acute, external force causes injury to the spinal cord, nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction occurs as a result of various medical conditions such as neuronal motor disease, tumor compression, infections, or vascular ischemia, among others [7, 8]. Thus, even before their diagnosis, individuals with nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction are often considered medically complex.

Evidence has shown that medical complexity and the associated potential polypharmacy (i.e., ≥5 concurrent medications) may be burdensome for patients and can lead to a plethora of negative consequences such as drug–drug interactions, potentially inappropriate prescribing, medication adherence issues, and negative treatment outcomes [9]. The addition of opioids may increase drug related problems. For example, opioids are often co-prescribed with a stool softener in anticipation of constipation (a potential adverse drug reaction to opioids), which increases the complexity of the medication regimen. Furthermore, opioids have acute respiratory depressant properties that have been linked with fatal and nonfatal poisonings in individuals with spinal cord injury as well as general populations [10]. Opioids are also habit forming, making patients susceptible to opioid use disorder [11, 12].

Although individuals with nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction represent more than half of all spinal cord injury cases in an inpatient rehabilitation setting [13], there remains a paucity of research on this population to guide their care. Given the unknown but potentially high prevalence of opioid use and the potential adverse events associated, it is of the utmost importance to understand the individuals with nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction who receive opioids as well as the factors that may predispose this group to prescription opioid use. Thus, the present study aimed to determine the prevalence and predictors of prescription opioid use in the year following inpatient rehabilitation for nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction.

Methods

Setting

We conducted a population-based retrospective cohort study of Ontarians with nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction using linked administrative data from ICES (formerly the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences), Toronto, Ontario (www.ices.on.ca). Ontario has a universal health insurance plan which covers healthcare services such as physician visits, hospitalizations, continuing care and inpatient rehabilitation care, and is the most populous Canadian province (almost 15 million ethnically diverse residents as of 2020) [14]. ICES is an independent, nonprofit research institute funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. As a prescribed entity under Ontario’s privacy legislation, ICES is authorized to collect and use healthcare data for the purposes of health system analysis, evaluation, and decision support. Secure access to these data is governed by policies and procedures that are approved by the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario. The use of data was authorized under section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act, which does not require review by a Research Ethics Board. However, this study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University of Toronto.

Data sources

Databases at ICES are often used in epidemiological studies [15,16,17]. These data are valid and reliable, as described by numerous studies [18,19,20]. These datasets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES. We used the Ontario Registered Persons database to capture demographic information and the Ontario Drug Benefits (ODB) database to identify the cohort of individuals eligible for provincial drug coverage as well as their prescription medication dispensing records. In Ontario, eligibility for ODB coverage includes disability, residence in long-term care facilities, receipt of home care services, high prescription medication fees compared to net household income, and being 65 years or older. We captured all records of hospitalizations (admission, transfer, and discharge dates) as well as procedures and diagnoses that occurred in hospital using the Discharge Abstract Database. We identified records of ambulatory visits using the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System and records of outpatient physician visits and physician specialty information using the Ontario Health Insurance Plan database. We extracted records of admission and diagnostic information on patients in inpatient rehabilitation care from the National Rehabilitation Reporting System. We obtained records of chronic comorbidities diagnosed using several ICES-derived databases including the Ontario Asthma Dataset, Congestive Heart Failure Database, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Database, Ontario Hypertension Dataset, Ontario Diabetes Dataset, Ontario Rheumatoid Arthritis Dataset, and the Ontario Dementia Database.

Population

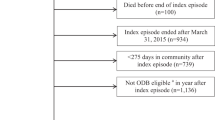

We used a previously defined cohort of adults eligible for provincial drug coverage who were admitted for rehabilitation after a nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction between April 1, 2004 and March 31, 2015 [21]. Although there are some instances of congenital nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction affecting younger individuals, the care management and health systems structure for pediatric populations is very different from adult populations. Thus, we chose to limit our cohort to adults 18 years of age and above. Those who died before discharge from inpatient rehabilitation, did not live in the community for at least 275 days in the year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation or those who were not eligible for provincial drug coverage for at least a year prior to the nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction were excluded from the study. The 275 day threshold ensures the ability to capture outpatient opioids dispensed and has been used previously for pharmacoepidemiological studies in Canada [22, 23]. Additionally, we required the full year of provincial drug coverage prior to index in order to capture previous medication use.

Variables of interest

The outcome of interest in this study was opioid use during the year after discharge from rehabilitation, defined as evidence of at least one prescription opioid dispensed at any time in the 1 year after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation for nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction. We did not link instances of inpatient rehabilitation to previous healthcare encounters, therefore the exact number of inpatient rehabilitations that occurred directly after acute hospitalization and/or diagnoses for nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction in our cohort is unknown. Given the etiology of nontrauma and the challenges in identification from acute or primary care, we captured individuals from inpatient stay where we have established codes to identify individuals [24]. We also captured a number of other independent variables in order to describe the cohort and identify predictors of opioid use after discharge. These included age, sex and neighborhood income quintile on the date of admission to inpatient rehabilitation, previous comorbidities, previous medication use, continuity of care, and length of stay in inpatient rehabilitation care.

We captured a number of previously diagnosed comorbidities and medications that are common for patients with spinal cord injuries [7, 10]. Chronic conditions (asthma, congestive heart failure, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, rheumatoid arthritis, dementia, hypertension, and psychiatric disorders; see Supplementary Appendix for diagnosis codes) were identified at any time prior to inpatient rehabilitation using a previously defined macro to identify multimorbidity commonly used in pharmacoepidemiological studies [25]. This macro defined diagnoses of nonpsychiatric chronic conditions in our study using ICES-derived algorithms and psychiatric conditions as any one inpatient diagnostic code or ≥2 outpatient physician billing codes (see Supplementary Appendix for diagnosis codes). Concurrent comorbidity was determined using the Johns Hopkins ACG® System Ver. 10 during the 2 years prior to inpatient rehabilitation and categorized into number of Aggregated Diagnosis Groups (ADG). Previous medication use and instances of healthcare services utilization such as physician visits were captured during the 1 year prior to inpatient rehabilitation. Functional status was determined using the Functional Independence Measure (FIM) score assessed at discharge from rehabilitation (higher functional status is represented by higher scores) [26].

We used a previous definition to identify continuity of care [21]. The number of visits conducted with the most commonly billed ambulatory care physician during the observation window was divided by the total number of physician visits during the same period. A patient was categorized as having high continuity of care when ≥75% of physician visits were conducted with the same physician while low continuity of care was considered when <50% of physician visits were made to one physician. The purpose of using 50% of visits as a threshold for continuity of care is to determine if an individual connects with one provider for the majority of their healthcare services. The threshold for high continuity of care (75% of visits) was used to determine any additional benefit or detriment of having continuity significantly beyond 50%. Patients with fewer than three physician visits during the observation window were not assessed for continuity of care.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to examine the cohorts’ demographic and clinical characteristics. We stratified the reporting of demographic and clinical characteristics based on age (<66 years versus ≥66 years) since nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction tends to occur in older adults [27] and therefore characteristics may differ based on age. Records of medication dispensing for individuals 65 years and above are captured in the ODB database, therefore a cut off of 66 years was chosen to ensure full medication records during the 1-year lookback. These differences were compared using Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney tests for medians, t tests for means, Cochran–Armitage tests for ordinal characteristics, and chi-squared tests for categorical characteristics. A test with an alpha level of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We used a Poisson multivariable regression model with robust standard errors to determine predictors of opioid use after discharge as a binary outcome. We calculated relative risks with 95% confidence intervals. All analyses were conducted at ICES using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA; www.sas.com).

Results

A total of 3468 individuals with nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction were captured using our study’s inclusion criteria. In this cohort, 1159 (33%) were under 66 years of age while 2309 (67%) were 66 and above (Table 1). Sex and income quintiles were distributed almost evenly with 1746 (50%) males and approximately 20% of the cohort in each neighborhood income quintile. Income characteristics differed slightly when stratified based on age (<66 versus ≥66 years) however, this is expected since eligibility for provincial drug coverage under 65 is limited largely to individuals with lower income among other criteria. In terms of health services utilization, the cohort had a median (interquartile range (IQR)) of 8 (4–13) family physician visits and 6 (3–11) specialist visits in the 1 year prior to inpatient rehabilitation. Median (IQR) length of inpatient rehabilitation stay was 4 (2–7) weeks, with individuals under the age of 66 having a significantly lower length of stay than those 66 and above (5 median weeks, IQR = 3–9 vs. 4 median weeks, IQR = 2–7). The cohort had a high level of concurrent comorbidity as evidenced by a median (IQR) ADG score of 10 (8–13). A significantly higher proportion of those 66 years of age and older tended to be diagnosed with more comorbidities (Table 2). In terms of opioid use, 60% (N = 2062) of the cohort were dispensed a prescription opioid following inpatient rehabilitation. When stratified based on age, a higher proportion of younger individuals (N = 749; 65%) were dispensed prescription opioids than older individuals (N = 1313; 57%).

Predictors of opioid use after discharge

We modeled a number of variables to determine their association with future opioid use (Fig. 1). Being female (Relative risk [RR] 1.14, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.08–1.20), diagnosis of osteoarthritis (RR 1.19, 95% CI 1.11–1.29), prior opioid use (RR 1.77, 95% CI 1.67–1.88), lower continuity of care (low: RR 1.10, 95% CI 1.00–1.20; medium: RR 1.13, 95% CI 1.03–1.23), prior mental health diagnosis (RR 1.19, 95% CI 1.13–1.26), and increasing ADG score (RR 1.03, 95% CI 1.03–1.04 per ADG) were significantly associated with future opioid use. FIM scores of 103–111 (RR 1.14, 95% CI 1.05–1.25), and 112–117 (RR 1.14, 95% CI 1.05–1.25) were significantly associated with a higher risk of subsequent opioid use when compared to higher FIM scores of >117. Increasing week of inpatient rehabilitation stay was slightly protective (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.98–0.99) against future opioid use, as was higher income. Risk of the outcome of interest varied with age, which was modeled as a continuous variable. Younger individuals had a significantly higher risk of future opioid use, a risk that peaked around 30–40 years of age (RR 1.54, 95% CI 1.42–1.66 for age 40, as compared to age 80). Relative risk of opioid use following discharge decreased as age increased beyond 40 years (Fig. 2).

Reference categories are indicated in brackets: female (male), income quintile 2–5 (income quintile 1, lowest income level), low and medium continuity of care (high continuity of care), osteoarthritis (no osteoarthritis diagnosis), prior mental illness diagnosis (no previous mental illness diagnosis) FIM scores (117+ FIM score), and prior opioid use (no prior opioid use). ADG Aggregated Diagnosis Groups (measure of morbidity), FIM Functional Independence Measure (measure of functional status, lower score refers to lower functional status).

Discussion

In this population-based cohort study, we sought to determine the prevalence and predictors of prescription opioid use in the year following discharge from inpatient rehabilitation for nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction. Our cohort included 3468 individuals who met our study criteria between April 1, 2004 and March 31, 2015 and we found that over half of this group (60%; N = 2062) had a record of prescription opioids dispensed in the year following discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Prescription opioid use during this time period was higher in younger individuals (<66 years of age) than older adults (≥66 years of age) and risk factors for future prescription opioid use included being female, diagnosis of osteoporosis, prior exposure to prescription opioids, higher ADG score, and lower functional status.

The prevalence of opioid use in our cohort of individuals with nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction (60%) is substantially higher than previously reported figures for prescription opioid use among individuals with traumatic spinal cord injury in Ontario (35%) [23] and the United States (51%) [10] as well as the general population in Ontario (12%) [28]. Although the Ontario rates for traumatic spinal cord injury in the aforementioned study [23] were calculated using prescription opioid claims from all Ontario community pharmacies rather than prescription opioid claims for Ontarian public drug beneficiaries as in the current study, the considerably higher rate reported here is likely not due to methodological differences. Rather, our findings underscore the high level of medical complexity of individuals with nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction. Individuals in our cohort had a considerably higher prevalence of comorbidities that result in pain (e.g., almost 25% of our cohort were previously diagnosed with cancer compared to almost 11% of the traumatic spinal cord injury cohort [23]). Combined with the paucity of literature currently available on this population, the results of the present study highlight the need for further research on individuals with nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction so clinicians and caregivers can provide evidence-based care.

Interestingly, although we found that higher morbidity (i.e., increasing ADG score) and lower functional status (characteristics often seen in older adults) were associated with future opioid use, we also observed that prescription opioids were dispensed at a higher rate among younger individuals (<66 years of age). It is possible that older adults (≥66 years of age) may be using alternative methods of analgesic therapy, as opioids are considered potentially inappropriate medications for older adults [29] and this should be explored further in future research. However, the higher rate of prescription opioid use among younger individuals remains a concern, as younger individuals are often more susceptible to adverse consequences of opioids such as opioid use disorder and opioid-related fatalities [30]. In Ontario between 2013 and 2016, approximately 93% of those who died of an opioid-related death and had an active opioid prescription at the time of death were under the age of 65 [30]. Future research should also examine opioid-related adverse events among individuals with nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction to determine whether this high prevalence of use is safe.

The identification of preexisting mental illness as a significant predictor for future opioid use is also an important point of clinical consideration. In a large cohort study conducted by Scherrer et al. using administrative data in the United States, the authors found that exposure to opioids is associated with more than a twofold increase in the risk of depression recurrence, independent of pain level [31]. Based on our findings, this may be particularly problematic for patients with nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction and therefore any addition of opioids, a medication that may trigger depressive symptoms, should be carefully considered by clinicians before prescribing.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations in this study that warrant discussion. First, the cohort is restricted to beneficiaries of Ontario’s public drug program. Individuals eligible for such benefits are mostly older adults (≥65 years of age), those who are financially disadvantaged or have a disability. Although this cohort may not be representative of the overall Ontario population and we may be underreporting the prevalence of opioid use for those under 65 years of age who are not eligible for provincial drug benefits, results from this study can be applied to older adult populations, where a large proportion of nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction typically occurs. Second, we required that individuals discharged from inpatient rehabilitation live in the community for 275 of the 365 days after discharge in order to avoid potential underreporting of opioids dispensed. This may have unintentionally created a healthier cohort of individuals who survived for >275 of the 365 days, therefore the true prevalence may be even higher than reported. Additionally, while our data does not include results from the ASIA Exam, functional status is reported using the FIM. We have included Rehabilitation Client Groups in the supplemental appendix to provide further information on the types of spinal cord dysfunction in this cohort. Furthermore, our study did not identify the indication of opioids prescribed even though the potential risk associated with a course of opioids for cough suppression may differ from that of opioid therapy for pain. We chose to focus our outcome on overall opioid use because there is no published literature on this. We also note that time since injury is challenging to identify for nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction due to the complex etiology and differences in pathways for diagnoses. Individuals may experience symptoms for differing periods of time prior to diagnosis and admission to inpatient rehabilitation, a variable unavailable in our datasets [32]. Instead, we used length of stay at an inpatient rehabilitation facility as a proxy for time since injury. Furthermore, we did not capture the year during which opioids were prescribed despite potential gradual changes in prescribing practices over the course of our study period. Finally, our data only captures records of prescription opioid dispensed and does not capture instances of over-the-counter nor illicit opioid use, therefore it is possible that a higher proportion of individuals may be exposed to this drug class than reported.

Conclusion

The present study showed that a substantial portion (59.5%) of individuals experiencing nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction in Ontario are dispensed prescription opioids in the year following discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Due to the plethora of severe complications often associated with opioid use, it is important to conduct further research on opioid use in this population in order for clinicians and caregivers to help manage their patients’ pain in a safe and effective manner.

Data availability

The data used in this study are securely housed in an encrypted form at ICES. Data agreements prohibit ICES from sharing these datasets publicly, however confidential access may be granted through the Data & Analytics Services at ICES. Additional information is available at www.ices.on.ca/DAS.

References

Cadel L, DeLuca C, Hitzig SL, Packer TL, Lofters AK, Patel T, et al. Self-management of pain and depression in adultswith spinal cord injury: A scoping review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2020;43:280–97.

Guy SD, Mehta S, Casalino A, Côté I, Kras-Dupuis A, Moulin DE, et al. The CanPain SCI clinical practice guidelines for rehabilitation management of neuropathic pain after spinal cord: recommendations for treatment. Spinal Cord. 2016;54:S14–23.

Hadjipavlou G, Cortese AM, Ramaswamy B. Spinal cord injury and chronic pain. BJA Educ. 2016;16:264–8.

Gomes T, Mamdani MM, Dhalla IA, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN. Opioid dose and drug-related mortality in patients with nonmalignant pain. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:686–91.

Gomes T, Redelmeier DA, Juurlink DN, Dhalla IA, Camacho X, Mamdani MM. Opioid dose and risk of road trauma in Canada: a population-based study. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:196.

Gomes T, Greaves S, Martins D, Bandola D, Tadrous M, Singh S, et al. Latest trends in opioid-related deaths in Ontario: 1991 to 2015. Ont Drug Policy Res Netw. 2017. http://odprn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/ODPRN-Report_Latest-trends-in-opioid-related-deaths.pdf.

Guilcher SJT, Munce SEP, Couris CM, Fung K, Craven BC, Verrier M, et al. Health care utilization in non-traumatic and traumatic spinal cord injury: a population-based study. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:45–50.

Guilcher SJT, Voth J, Ho C, Noonan VK, McKenzie N, Thorogood NP, et al. Characteristics of non-traumatic spinal cord dysfunction in Canada using administrative health data. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2017;23:343–52.

Duerden M, Avery T, Payne R. Polypharmacy and medicines optimisation: making it safe and sound [Internet]. The King’s Fund; 2013. p. 1–4. Available from: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/polypharmacy-and-medicines-optimisation-kingsfund-nov13.pdf.

Hand BN, Krause JS, Simpson KN. Dose and duration of opioid use in propensity score–matched, privately insured opioid users with and without spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99:855–61.

Alam A, Juurlink DN. The prescription opioid epidemic: an overview for anesthesiologists. Can J Anesth. 2016;63:61–8.

Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, Buckley DN, Wang L, Couban RJ, et al. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. Can Med Assoc J. 2017;189:E659–66.

Ge L, Arul K, Ikpeze T, Baldwin A, Nickels JL, Mesfin A. Traumatic and nontraumatic spinal cord injuries. World Neurosurg. 2018;111:e142–8.

Statistics Canada. Table 17-10-0009-01 Population estimates, quarterly. https://doi.org/10.25318/1710000901-eng.

Gomes T, Martins D, Tadrous M, Paterson JM, Shah BR, Juurlink DN, et al. Self-monitoring of blood glucose levels: evaluating the impact of a policy of quantity limits on test-strip use and costs. Can J Diabetes. 2016;40:431–5.

Cressman AM, Macdonald EM, Huang A, Gomes T, Paterson MJ, Kurdyak PA, et al. Prescription stimulant use and hospitalization for psychosis or mania: a population-based study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35:667–71.

Bronskill SE, Campitelli MA, Iaboni A, Herrmann N, Guan J, Maclagan LC, et al. Low-dose trazodone, benzodiazepines, and fall-related injuries in nursing homes: a matched-cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:1963–71.

Ackroyd-Stolarz S, Bowles S, Giffin L. Validating administrative data for the detection of adverse events in older hospitalized patients. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2014;6:101–8.

Levy AR, O’Brien BJ, Sellors C, Grootendorst P, Willison D. Coding accuracy of administrative drug claims in the Ontario Drug Benefit database. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;10:67–71.

Steele LS, Glazier RH, Lin E, Evans M. Using administrative data to measure ambulatory mental health service provision in primary care. Med Care. 2004;42:960–5.

Guilcher SJT, Hogan M-E, McCormack D, Calzavara AJ, Hitzig SL, Patel T, et al. Prescription medications dispensed following a nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction: a retrospective population-based study in Ontario, Canada. Spinal Cord. 2020. http://www.nature.com/articles/s41393-020-0511-x.

Hanley GE, Morgan S, Reid RJ. Explaining prescription drug use and expenditures using the adjusted clinical groups case-mix system in the population of British Columbia, Canada. Med Care. 2010;48:402–8.

Guilcher SJT, Hogan M-E, Guan Q, McCormack D, Calzavara A, Patel T, et al. Prevalence of prescribed opioid claims among persons with traumatic spinal cord injury in Ontario, Canada: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020. (In Press). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2020.06.020.

Jaglal SB, Voth J, Guilcher SJT, Ho C, Noonan VK, McKenzie N, et al. Creation of an algorithm to identify non-traumatic spinal cord dysfunction patients in Canada using administrative health data. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2017;23:324–32.

Koné Pefoyo AJ, Bronskill SE, Gruneir A, Calzavara A, Thavorn K, Petrosyan Y, et al. The increasing burden and complexity of multimorbidity. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:415.

Chehata VJ, Shatzer M, Cristian A. Chapter 3—Inpatient rehabilitation outcome measures in persons with brain and spinal cord cancer. In: Central nervous system cancer rehabilitation. St. Louis, Missouri, USA: Elsevier; 2019.

New PW, Eriks-Hoogland I, Scivoletto G, Reeves RK, Townson A, Marshall R, et al. Important clinical rehabilitation principles unique to people with non-traumatic spinal cord dysfunction. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2017;23:299–312.

CIHI. Canadian Institute for Health Information: opioid prescribing in Canada: how are practices changing? 2019. https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/opioid-prescribing-canada-trends-en-web.pdf.

American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:674–94.

Gomes T, Khuu W, Martins D, Tadrous M, Mamdani MM, Paterson JM, et al. Contributions of prescribed and non-prescribed opioids to opioid related deaths: population based cohort study in Ontario, Canada. BMJ. 2018;29:k3207.

Scherrer JF, Salas J, Copeland LA, Stock EM, Schneider FD, Sullivan M, et al. Increased risk of depression recurrence after initiation of prescription opioids in noncancer pain patients. J Pain. 2016;17:473–82.

New PW, Marshall R. International spinal cord injury data sets for non-traumatic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2014;52:123–32.

Funding

This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information. The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources and partners. No endorsement by ICES, the Ontario MOHLTC, or the Canadian Institute of Health Information is intended or should be inferred. This study was funded by a Connaught New Investigator Award (University of Toronto), and the Craig H. Neilsen Psychosocial Research Pilot grant (PSR2-17, grant #441259). SJTG is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Embedded Clinician Scientist Salary Award on Transitions in Care working with Ontario Health (Quality). AKL is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Award, as a Clinician Scientist at the University of Toronto Department of Family & Community Medicine, and as the Chair in Implementation Science at the Peter Gilgan Center for Women’s Cancers at Women’s College Hospital in partnership with the Canadian Cancer Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SJTG, MEH, AC, AKL, TP (Tanya Packer), SLH, and TP (Tejal Patel) were responsible for designing the protocol. AC and DM conducted the data analysis, while QG, SJTG, AC, and MEH interpreted the data. QG drafted the paper and all authors contributed to providing feedback for the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The use of data in this study was authorized under section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act, which does not require review by a Research Ethics Board. However, this study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University of Toronto.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guan, Q., Hogan, ME., Calzavara, A. et al. Prevalence of prescribed opioid claims among persons with nontraumatic spinal cord dysfunction in Ontario, Canada: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Spinal Cord 59, 512–519 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-00605-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-00605-1