Abstract

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the ventral internal capsule/ventral striatum (VCVS) is an emerging treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Recently, multiple studies using normative connectomes have correlated DBS outcomes to stimulation of specific white matter tracts. Those studies did not test whether these correlations are clinically predictive, and did not apply cross-validation approaches that are necessary for biomarker development. Further, they did not account for the possibility of systematic differences between DBS patients and the non-diagnosed controls used in normative connectomes. To address these gaps, we performed patient-specific diffusion imaging in 8 patients who underwent VCVS DBS for OCD. We delineated tracts connecting thalamus and subthalamic nucleus (STN) to prefrontal cortex via VCVS. We then calculated which tracts were likely activated by individual patients’ DBS settings. We fit multiple statistical models to predict both OCD and depression outcomes from tract activation. We further attempted to predict hypomania, a VCVS DBS complication. We assessed all models’ performance on held-out test sets. With this best-practices approach, no model predicted OCD response, depression response, or hypomania above chance. Coefficient inspection partly supported prior reports, in that capture of tracts projecting to cingulate cortex was associated with both YBOCS and MADRS response. In contrast to prior reports, however, tracts connected to STN were not reliably correlated with response. Thus, patient-specific imaging and a guideline-adherent analysis were unable to identify a tractographic target with sufficient effect size to drive clinical decision-making or predict individual outcomes. These findings suggest caution in interpreting the results of normative connectome studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is an emerging approach to treatment-resistant mental disorders [1,2,3], but response rates in formal clinical trials are mixed [1, 4,5,6,7]. More reliable outcomes might be achieved by improving anatomic targeting. As psychiatric disorders are increasingly understood as network disorders [8, 9], psychiatric DBS is moving away from using a single nucleus/structure as the target and towards attempts at affecting networks [1, 10,11,12]. There is particular enthusiasm for identifying target networks through diffusion tractography, which may enable DBS electrode placement to be customized to individual patients’ anatomy. Although there is controversy over how accurately tractography reconstructs white matter anatomy [13, 14], remarkable early results have been reported from DBS placement based on that imaging [10]. Further, there are multiple tools available to model the interaction of DBS electric fields and targeted tracts [15,16,17]. These tools could replace trial-and-error DBS programming with a mathematically optimal approach to activating desired pathways while minimizing off-target effects [18]. That could overcome the difficulty of correctly programming stimulation, a likely driver of inconsistent clinical outcomes [1, 4, 19].

To realize that promise, we need to know which tracts should/should not be stimulated. For DBS of the subcallosal white matter for depression, multiple groups have settled on a specific white matter confluence and are studying it prospectively (with varying clinical outcomes [10, 20]). For obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), a consensus may also be emerging. A theory linking OCD to dysfunction in cortico-striato-thalamic connectivity [21, 22] has led to a focus on white matter tracts linking prefrontal cortex (PFC) to striatum, basal ganglia, and thalamus. Retrospective studies from multiple institutions have implicated tracts to/from dorsolateral PFC [23, 24], ventrolateral PFC [12, 25, 26], and anterior cingulate [12, 24] as potentially important in response. Recent analyses of patients implanted at two different targets correlated OCD response with a tract linking the ventral internal capsule/striatum (VCVS) and the subthalamic nucleus (STN) with the medial PFC [12, 26,27,28,29]. One study further suggested that capture of tracts from orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) [23] led to non-response, although a qualitative synthesis [30] suggests that effective DBS tends to activate OFC-related fibers, and OFC-directed circuits can drive compulsive behaviors in animal models [31,32,33].

Although promising, these prior tractographic analyses are also limited. Many used standard atlases or connectomes derived from healthy controls, comparing these maps against electric fields from patient-specific DBS placements [12, 23, 27, 28]. Individual patients, however, show dramatic variation in their white matter topography compared to atlas standards [34]. Targeting maps computed using “normative” connectomes differ from those computed from patient-specific DTI images [24]. Other studies used simple isotropic field models [25], or distance between electrodes and a target tract [35] which may not accurately capture the DBS-induced electric field [16, 36].

Most importantly, these analyses focused on tracts that correlate with clinical response. A variable may correlate strongly with an outcome but not be able to reliably predict that outcome, e.g. if the means are separate but the tails of two distributions overlap [37,38,39]. Best practices in biomarker research suggest explicitly building predictive models, testing those models on held-out data, and reporting predictive performance in addition to correlation [37, 38, 40, 41]. Prediction-oriented analyses might better answer the question of whether a tractographic finding can be used as a programming target, i.e. whether it has strong predictive accuracy at the single-patient level [42].

Here, we address these limitations through an explicit attempt to predict single-patient response to DBS for OCD at the VCVS target, based on more precise field modeling approaches and using patient-specific tractography. We replicate in part prior studies’ findings that cingulate, medial PFC, and lateral PFC tracts are correlated with clinical response, but we show that these correlations do not provide strong clinical predictive power, and in some cases, we identify correlations that contradict earlier reports.

Methods

Study population and clinical treatment

Participants were 6 patients who enrolled in a clinical trial (NCT00640133) of VCVS DBS for OCD [43], plus 2 who received VCVS DBS for OCD under a Humanitarian Device Exemption. All patients had sufficiently severe OCD at baseline to qualify for DBS (Table S1). All patients received Medtronic model 3387 DBS leads, with the most ventral contact targeted to the ventral striatal grey matter. The Institutional Review Boards of Massachusetts General Hospital and Butler Hospital approved the protocols and provided ethical oversight. All participants gave informed consent, explicitly including separate consent for DBS and for neuroimaging. We report here all patients who agreed to undergo imaging. We analyzed both the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (YBOCS) and Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), collected at visits ~2–4 weeks apart by a trained rater. We did not limit our analysis to YBOCS and MADRS collected at specific timepoints, but used all available datapoints for which we also had recorded DBS settings.

Imaging and patient-specific tractography

Pre-operative MRI data were acquired on a 3T Siemens TimTrio scanner. Diffusion MRI (dMRI) scans had a spatial resolution of 2 mm (isotropic) with 10 non-diffusion weighted volumes and 60 diffusion weighted volumes, with gradient directions spread uniformly on the sphere with a b-value of 700 s/mm2. dMRI data were registered to pre-operative T1- and T2-weighted MRI images and post-operative CT scans using a published pipeline [44] available at https://github.com/pnlbwh/. We then performed whole-brain tractography from the dMRI data, using a multi-tensor unscented Kalman filter (UKF) [45, 46]. The UKF fits a mixture model of two tensors to the dMRI data, providing a highly sensitive fiber tracking ability in the presence of crossing fibers [47,48,49,50]. The UKF method guides each fiber’s current tracking estimate by the previous one. This recursive estimation helps stabilize model fitting, making tracking more robust to imaging artifact/noise. Another benefit of UKF is that fiber tracking orientation is controlled by a probabilistic prior about the rate of change of fiber orientation, producing more accurate tracking than the hard limits on curvature used in typical tractography algorithms. We combined the UKF with a fiber clustering algorithm to create an anatomically curated and annotated white matter atlas [49]. The clustering method groups the streamlines from each patient using a spectral embedding algorithm. Each fiber cluster is matched to a tract from an a priori labeled atlas of the white matter derived from known connections in monkey and human brains. Fiber clustering was performed only on streamlines longer than 40 mm to annotate medium and long range tracts.

Tract activation modeling

For each clinical DBS setting used in each patient, we calculated the volume of tissue activated (VTA) using a modified version of StimVision [15]. This comprised 150 parameter sets, measured over 2–5 years for each patient. During this time, clinicians were actively programming devices and altering settings, leading to substantial fluctuations in VTAs and tract engagement. Briefly, the VTAs were calculated using artificial neural network predictor functions, which were based on the response of multi-compartment cable models of axons coupled to finite element models of the DBS electric field [51]. The VTAs used in this study were designed to estimate the spatial extent of activation for large diameter (5.7 µm) myelinated axons near the DBS electrode [52].

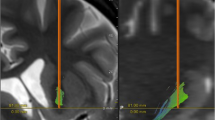

Based on theories that VCVS DBS acts by modulating circuits that run primarily in the internal capsule [14, 22, 30], we estimated activation of pathways linking thalamus with anterior cingulate and pericingulate cortex (ACC-PAC), dorsolateral PFC (dlPFC), ventrolateral PFC (vlPFC), dorsomedial PFC (DMPFC), medial orbitofrontal cortex (MOFC) and lateral OFC (LOFC). Pericingulate cortex includes rostral pre-cingulate cortex, but not the dorsal prefrontal cortex (such as the supplementary motor area). The atlas-guided fiber clustering algorithm [49] and a fiber clustering pipeline [53, 54] guided manual delineation of fiber bundles connecting these regions to thalamus. All pathway labelings were performed by an expert neuroanatomist (Dr. Makris). Examples of the traced bundles and their intersections with DBS VTAs are shown in Fig. 1A. Recent reports found that a tract connecting subthalamic nucleus (STN) to medial prefrontal cortex was strongly associated with clinical response to DBS in OCD [12, 26,27,28]. Therefore, we manually segmented the STN in each subject and extracted all fiber tracts connecting the STN with the prefrontal cortex (Fig. 1B). We verified that as the total charge delivered increased (leading to a larger VTA), the total number of activated fibers also increased (Fig. S1).

A Tract tracing and activation modeling examples. Shown are left/right oblique and axial views from one non-responder and one responder, with cortico-thalamic and cortico-STN tracts indicated by different colors. DBS leads are shown in teal and VTAs in red. In this panel, we show only tracts intersecting the VTAs for clarity. B Tracing of tracts between STN and frontal cortex, in the same responder as (A). To ensure capture of the tract reported in ref. [12], we broadly traced all streamlines originating in a seed around STN and extending anterior to the central sulcus. This includes fibers coursing dorsally to motor regions, and tracts as in ref. [12] connecting STN to ACC and medial PFC. Very few of these intersect the VTA in this patient, despite the good clinical response (YBOCS drop of 61% from baseline). To emphasize that point, this panel shows all fibers traced from the STN seed in this patient, regardless of VTA intersection.

Data analysis—independent/predictor variables

It is unclear whether the important “dose” of DBS is activation of a sufficient number of fibers (“total fiber” model), vs. the degree to which a sub-circuit is influenced (i.e., the fraction of the overall streamlines in a tract that are within the VTA, or a “percentage” model). We calculated both and fit them as two separate models for each dependent clinical outcome (see below). We also considered the possibility that DBS response is not determined by any individual tract/pathway, but instead requires capture of multiple pathways simultaneously. We, therefore, added a “total activation” variable to each prediction model. For total fiber models, this variable represented the total number of streamlines activated for all tracts. For percentage models, it represented the mean percentage activation across all reconstructed tracts. We standardized all input variables to the 0–1 interval to ensure that regression coefficients were comparable between independent variables.

All models were fit and evaluated using scikit-learn (0.24.1) in Python (3.8.5). With the exception of a necessary condition analysis described below, variables were coded at the single-visit level. That is, we predicted the clinical outcome at visit T from the DBS settings programmed at visit T-1.

Data analysis—OCD response

White matter pathway activation might relate tightly to the degree of clinical improvement (YBOCS as a continuous variable) or to patients’ overall well being (dichotomous responder/non-responder analysis). We thus modeled each separately. We analyzed continuous YBOCS as percentage decrease from baseline. Distribution fitting via the ‘fitdist’ package verified that YBOCS values were most compatible with a gamma distribution. We therefore predicted YBOCS improvement via an L1-regularized generalized linear regression (gamma distribution with identity link, Python package “pyglmnet”) and via a random forest regression with 100 trees. The dependent variable was percentage improvement in YBOCS. We compared these two approaches to assess whether conclusions might be sensitive to the model formulation. Regularized regression emphasizes selection of a small number of highly leveraged variables, which may be more helpful in defining clinical decision rules. Random forests can outperform generalized linear regression in at least some cases [55], particularly where there are nonlinearities better captured by thresholding.

We further analyzed categorical (non)response, defined as a 35% or greater YBOCS decrease from baseline [43]. For these, we compared an L1-regularized logistic regression and a random forest classifier with 100 trees. A minority of visits represented clinical response (29 visits out of 165, although 5 of 8 patients were in clinical response during at least one visit). To compensate for this imbalance, we applied the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE, [56]) with 3 nearest-neighbor examples. We chose L1 regularization for both regressions because dominant models of OCD argue that dysfunction in specific cortico-striatal loops leads to symptoms [21, 22] and/or that a relatively small number of fiber bundles can explain response [12, 26,27,28]. This should be reflected in clinical response being driven a small subset of tracts.

Data analysis—depression response

VCVS may have more effects on mood than on compulsivity [57], which would be reflected in better prediction of mood (MADRS) than of YBOCS. We applied the modeling pipeline used for categorical YBOCS response to categorical MADRS response, defined as a 50% or greater MADRS decrease from pre-surgical baseline. 7 out of the 165 visits met MADRS response criteria, although this again represented 5 of 8 patients.

We further assessed tractographic models’ prediction of hypomania, a known and voltage-dependent complication of VCVS DBS [58, 59]; details are in the Supplement.

Data analysis—model evaluation

All categorical data sets were unbalanced, and the outcome of clinical interest was always the minority class. We, therefore, report balanced accuracy and recall (performance for the minority class) for the categorical dependent variables. Further, we report the area under the receiver operator curve (AUC), which is suggested to be the best summary of a categorical biomarker’s performance [37, 40]. For continuous YBOCS prediction, we report the fraction of variance explained and the coefficient of determination (R2). We emphasize that R2 here is not the square of a correlation coefficient [37].

All metrics were calculated on a held-out test set [37, 38, 40, 41]. For each model, we held out 2 random patients from the dataset (effectively 4-fold cross-validation with resampling). This improves over leave-one-out approaches, which can overstate predictive performance [60]. We left out 25% of patients, rather than visits, because data were highly autocorrelated visit-to-visit, which also falsely inflates performance [37]. We then fit the predictive model on the remaining 6 patients, and we report the performance on the visit-level data from the held out patients. To prevent data leakage, the SMOTE upsampling was performed on the training set only, after the split. We obtained confidence intervals for all metrics by repeating this process over all 28 possible leave-two-out combinations, then calculating the range of performance falling within 2 standard deviations of the median performance.

We fit 16 models (4 outcomes × 2 types of model × 2 ways of expressing activation), cross-validating within each model. We interpreted the outcomes using an uncorrected 95% confidence interval to maximize power.

Data analysis—predictor importance

To detect potentially relevant tracts, we performed importance scoring on all models, regardless of whether they correctly predicted the clinical outcomes. For regression models, we computed the median and standard deviation of the regression coefficient for each tract, across all the train-test splits. For random forests, we applied permutation importance as implemented in scikit-learn. We permuted each independent variable 5 times for each of the train-test splits.

Data analysis—alternative univariate approach

Recent papers [12, 26,27,28] used a different approach, based on comparison of VTAs to population-scale tractography. As an additional analysis (not pre planned), we attempted a similar approach on this dataset. We calculated all linear correlations between YBOCS improvement (continuous variable) and the activation of each individual tract (either as a total fiber or percentage activation). These correlations were performed on the training set after holding out 2 random patients, consistent with [12]. To test whether this approach produced more generalizable predictors of DBS response, we used the same data to fit a univariate linear regression for each independent variable, then evaluated the model performance (coefficient of determination, R2) on the 2 held out patients.

In a further exploratory analysis (see Supplement), we considered whether DBS outcomes depended not on the tracts activated, but the integrity of those tracts.

Data analysis—statistical power

Because our sample size is relatively small compared to other recent studies [12], we assessed the clinical effect size that we could reasonably have hoped to detect. We simulated a dataset with a known tract/outcome correlation rtrue ranging from 0 to 1, with 100 replicates at each putative rtrue value. We then calculated the fraction of times that our modeling approach identified statistical significance, both for a primary metric (AUC) and our secondary metric (size of the regression parameter for the putative predictive tract).

Results

Clinical outcomes—YBOCS

The mean YBOCS improvement (considering each patient’s best time point) was 46.6%, and 5 of the 8 patients (62.5%) were clinical responders (≥35% YBOCS drop) for at least one visit.

No tract reliably predicted continuous YBOCS improvement. By all metrics, model performance was worse than chance on the held-out test set (Table 1), for both total-activation and percentage-activation models. Consistent with this, no coefficients in the regression models were above zero (i.e., the dataset mean was more reliable than any tractographic predictor). In the random forest models, the highest importance was percentage activation of fibers connecting thalamus to left OFC, but this was at chance level (change in R2 across models: mean 0.09, SD 0.24).

Similarly, no model exceeded chance for response/nonresponse prediction (Table 2). In the logistic regression, highly weighted features across models were the number (but not percentage) of activated streamlines connecting thalamus to left cingulate, lateral OFC, medial OFC, and vlPFC. Cingulate and lateral OFC streamline activation were positively associated with response, whereas medial OFC and vlPFC activation were negatively associated (Fig. 2). For all of these tracts, the confidence interval for the coefficient estimated across all train-test splits included 0. These findings were sensitive to the modeling approach; the same tracts did not show median importance scores different from 0 in the random forest models. The ACC-PAC findings were corroborated by a Necessary Condition Analysis on white matter integrity (Supplementary Results).

All confidence intervals include 0, with left medial OFC (non-response) and left ACC (response) coming closest to significance. All reported results are for total fiber capture; percentage capture did not have non-zero coefficients in this analysis. Data are coded such that positive regression coefficients represent clinical improvement.

The alternate mass-univariate approach also did not reliably predict response on the held-out test sets (Table 3). It was concordant with the categorical response analysis in that it identified streamlines connecting the left cingulate to thalamus as correlated with response, and similarly streamlines from bilateral vlPFC as correlated with non-response. There was more discordance than similarity, however. The medial OFC tracts identified by regression were not selected in the mass univariate approach, and conversely, the mass univariate approach predicted nonresponse if tracts projecting to dlPFC were within the VTA. Further, the mass univariate approach emphasized percentage capture, while the logistic regression emphasized total fibers within a VTA. We note that tracts from STN to PFC were negatively correlated with clinical outcomes, whereas prior reports identify them as positively correlated [12, 27, 28].

Clinical outcomes—MADRS

The mean MADRS improvement (considering each patient’s best time point) was 55.69%, and 5 of the 8 (62.5%) were responders (≥50% MADRS drop) at some point. Mood and OCD response were not linked (r = 0.13 for correlation between response status on YBOCS and MADRS). Consistent with other reports [57], there were more observations of MADRS response without YBOCS than of YBOCS response without MADRS (22 vs. 4).

No model reliably predicted MADRS response above chance (Table S1). For comparison with the YBOCS analysis, we further examined the non-zero coefficients of the total-fiber regression. Capture of streamlines between right cingulate and thalamus was correlated with MADRS response, and the confidence interval for this coefficient excluded zero (Fig. S1). This was not true of any other tract. Left vlPFC was associated with non-response (as it was in the categorical YBOCS analysis), but the distribution of coefficients across analyses included zero. Random forest importance scores were centered around zero.

Power analysis and detection bounds

Even with its relatively small sample size, the repeated-measures design of our analysis granted 90% power for detection of a tract-to-outcome correlation as low as 0.5 (Fig. 3), which is smaller than the reported correlations in the largest available normative dataset [12]. Critically, there was a large gap between sensitivity for clinical prediction (based on AUC) and sensitivity for the correlation itself (based on the regression coefficient). For the latter, we retained 90% power for detection of a correlation as low as 0.2.

Discussion

Our results are both concordant and discordant with prior efforts to predict clinical OCD DBS response from tractographic modeling of cortico-striatal and cortico-basal circuits. Critically, we implemented multiple analytic steps beyond prior studies: individualized, patient-specific tracts registered to individual lead placements, activation volume calculation beyond simple electric field assumptions, consideration of multiple clinical timepoints for each patient, and formal evaluation of predictive power (as compared to measurement of correlations between activation and response or group mean differences). With this more guideline-adherent approach, we found that no tract could reliably predict clinical response or complications, whether those were considered in a continuous or categorical approach. This is likely not a surprise—we and others have highlighted that group-level significant correlations/separations often do not have clinical predictive power [37,38,39,40]. In this sense, our results support calls for caution regarding the clinical role of tractography [16, 42]. We also showed that outcomes can be sensitive to the analytic approach—our random forest and regularized regression approaches produced very different results, even though both are commonly used approaches to prediction and variable selection.

Model inspection may offer some insight into variables for further investigation, even if pathway activation modeling approaches are not yet able to strongly predict response. Numerically, predictive power was greater (more non-zero regression coefficients after regularization) when predicting categorical rather than continuous outcomes. This may be because categorical outcomes effectively smooth out small fluctuations in continuous rating scales, fluctuations that may be primarily due to inter-rater variability or disease-unrelated variables rather than to DBS settings. The YBOCS in particular shows non-linear behavior at high scores that may exacerbate this [61]. We obtained non-zero regression coefficients for models using activated fiber counts, but not for percentage-activated models, implying that it is more important to get at least a portion of a key tract within the VTA. These results also make sense in the context of our finding that the integrity (traceability) of these tracts varies greatly between patients with OCD—a tract where response depends on tract integrity will have a large coefficient in a total-fibers model, but not in a percentage-activation model.

Our results in part support and in part diverge from a series of recent papers implicating pathways between PFC and basal ganglia as critical for OCD DBS [12, 26,27,28]. PAC to thalamus tracts were implicated in both YBOCS and MADRS response, and were the most positively weighted in our mass-univariate approach. Our white matter integrity analysis identified the same tracts as having the largest effect size (necessity). Also similar to that prior work, we found that activation of connections to medial OFC produced numerically worse outcomes. Inconsistent with the prior work [12, 26,27,28], we found negative correlations (in the mass univariate analysis) or null effects (in the predictive models) specifically for tracts connecting PFC to STN or vlPFC to thalamus. This again may reflect the importance of patient-specific imaging. Given that we have previously shown these tracts to have substantial inter-individual variability in their position within the internal capsule [34], and that here we note them to have similar variability in their overall integrity, a normative connectomic analysis may not reflect the actual fibers being successfully modulated in DBS cases. Alternatively, our results may highlight programming and surgical differences. These patients were implanted and programmed following the approach in [62], which emphasizes an initial search for a positive affective response. Other centers have reported very different programming algorithms [63], based more on standard anatomic positions. If response correlates with, e.g., the quality of concomitant therapy [26, 64] or general clinical expertise [65], those factors will likely be strongly correlated with the programming clinician, and thus will spuriously load onto the tracts and implant locations that clinician happens to prefer. Most importantly, our results highlight the importance of applying analyses designed specifically to identify clinical predictors [37]. Interestingly, we found that OFC engagement predicted worse OCD clinical response. OFC-originating components of cortico-striato-thalamic circuits are heavily emphasized in theoretical [21, 22, 30] and animal [31, 33, 66] models of OCD, and these findings may contribute to an ongoing debate over those models.

These results are tempered by three limitations. First, our sample size is small, consistent with the rarity of these patients [67]. Second, imaging was not performed on a connectome-optimized scanner. The 3T MRI used in this study has relatively weak gradients that influence our maximum image resolution. Scanning at 7 Tesla (as has now become more common [68]) might identify more tracts. Third, we used relatively simple models of DBS activation. All of these add noise, reducing our ability to detect subtle correlations, particularly given DTI’s susceptibility to false positives [14]. Practically, however, these limitations may not affect the clinical importance of our findings. We mitigated the lower resolution of these scans by use of an algorithm that is specifically designed to perform well in the presence of noise [46] and ensuring that our extracted tracts matched known, anatomically verified fiber bundles [49]. Regarding sample size, small samples tend to inflate effect sizes and bias towards positive conclusions [69], not the negative result we report. Most importantly, for a tractographic result to be sufficiently reliable to inform clinical targeting/programming, it would need to have a large and clear influence on outcomes, with robustness to minor variations in analytic or clinical technique. Such a large effect would be clearly detectable and consistent across studies even at small sample sizes, like the clinical effect of VCVS DBS, which shows consistent 60–70% response rates across many small to medium cohorts [57, 59, 70,71,72]. We verified this by showing that the present dataset would have been sufficient to identify a relatively modest tractography-to-outcome correlation of 0.5. In that context, failure to identify a significant predictor in this sample is relevant to both clinical practice and future study design. Our results identify the limits of current methods, and suggest a floor below which a biomarker would be unlikely to provide clinical value.

At the same time, our results support a growing argument that circuits linking ACC to thalamus and basal ganglia are important to VCVS DBS response. They dovetail with other work linking modulation of those circuits to increased cognitive control [73, 74], a construct that is thought to be deficient in OCD [75, 76]. Thus, these results do not imply that tractography and field modeling are non-useful for understanding DBS. They establish a gap between our current level of understanding (which can identify mechanistic hypotheses for follow up) and the level needed for clinical practice. With multiple technologies emerging to better verify target engagement and address patient heterogeneity [1, 16], that understanding will likely grow in coming years.

Data/Code availability

De-identified data tables and analysis code used to produce all exhibits in this manuscript will be available at the time of publication at https://github.com/tne-lab/Widge-Tractography-2021/.

References

Sullivan CRP, Olsen S, Widge AS. Deep brain stimulation for psychiatric disorders: From focal brain targets to cognitive networks. NeuroImage. 2021;225:117515.

Bari AA, Mikell CB, Abosch A, Ben-Haim S, Buchanan RJ, Burton AW, et al. Charting the road forward in psychiatric neurosurgery: proceedings of the 2016 American Society for Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery workshop on neuromodulation for psychiatric disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018;89:886–96.

Ramirez-Zamora A, Giordano J, Gunduz A, Alcantara J, Cagle JN, Cernera S, et al. Proceedings of the seventh annual deep brain stimulation think tank: advances in neurophysiology, adaptive DBS, virtual reality, neuroethics and technology. Front Hum Neurosci. 2020;14:54.

Widge AS, Malone DAJ, Dougherty DD. Closing the loop on deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:175.

Luyten L, Hendrickx S, Raymaekers S, Gabriëls L, Nuttin B. Electrical stimulation in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis alleviates severe obsessive-compulsive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:1272–80.

Holtzheimer PE, Husain MM, Lisanby SH, Taylor SF, Whitworth LA, McClintock S, et al. Subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: a multisite, randomised, sham-controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:839–49.

Dougherty DD, Rezai AR, Carpenter LL, Howland RH, Bhati MT, O’Reardon JP, et al. A randomized sham-controlled trial of deep brain stimulation of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum for chronic treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78:240–8.

Williams LM. Defining biotypes for depression and anxiety based on large-scale circuit dysfunction: a theoretical review of the evidence and future directions for clinical translation. Depress Anxiety. 2016;34:9–24.

Avena-Koenigsberger A, Misic B, Sporns O. Communication dynamics in complex brain networks. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2018;19:17.

Riva-Posse P, Choi KS, Holtzheimer PE, Crowell AL, Garlow SJ, Rajendra JK, et al. A connectomic approach for subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation surgery: prospective targeting in treatment-resistant depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:843–9.

Karas PJ, Lee S, Jimenez-Shahed J, Goodman WK, Viswanathan A, Sheth SA. Deep brain stimulation for obsessive compulsive disorder: evolution of surgical stimulation target parallels changing model of dysfunctional brain circuits. Front Neurosci. 2019;12:998.

Li N, Baldermann JC, Kibleur A, Treu S, Akram H, Elias GJB, et al. A unified connectomic target for deep brain stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3364.

Maier-Hein KH, Neher PF, Houde J-C, Côté M-A, Garyfallidis E, Zhong J, et al. The challenge of mapping the human connectome based on diffusion tractography. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1349.

Haber SN, Tang W, Choi EY, Yendiki A, Liu H, Jbabdi S, et al. Circuits, networks, and neuropsychiatric disease: transitioning from anatomy to imaging. Biol Psychiatry. 2020;87:318–27.

Noecker AM, Choi KS, Riva-Posse P, Gross RE, Mayberg HS, McIntyre CC. StimVision software: examples and applications in subcallosal cingulate deep brain stimulation for depression. Neuromodulation Technol Neural Interface. 2018;21:191–6.

Noecker AM, Frankemolle‐Gilbert AM, Howell B, Petersen MV, Beylergil SB, Shaikh AG, et al. StimVision v2: examples and applications in subthalamic deep brain stimulation for parkinson’s disease. Neuromodulation Technol Neural Interface. 2021;24:248–58.

Horn A, Kühn AA. Lead-DBS: a toolbox for deep brain stimulation electrode localizations and visualizations. NeuroImage. 2015;107:127–35.

Peña E, Zhang S, Patriat R, Aman JE, Vitek JL, Harel N, et al. Multi-objective particle swarm optimization for postoperative deep brain stimulation targeting of subthalamic nucleus pathways. J Neural Eng. 2018;15:066020.

Provenza NR, Matteson ER, Allawala AB, Barrios-Anderson A, Sheth SA, Viswanathan A, et al. The case for adaptive neuromodulation to treat severe intractable mental disorders. Front Neurosci. 2019; 13, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.00152

Ramasubbu R, Clark DL, Golding S, Dobson KS, Mackie A, Haffenden A, et al. Long versus short pulse width subcallosal cingulate stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: a randomised, double-blind, crossover trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:29–40.

Robbins TW, Vaghi MM, Banca P. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: puzzles and prospects. Neuron. 2019;102:27–47.

Dougherty DD, Brennan B, Stewart SE, Wilhelm S, Widge AS, Rauch SL. Neuroscientifically informed formulation and treatment planning for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:1081–7.

Hartmann CJ, Lujan JL, Chaturvedi A, Goodman WK, Okun MS, McIntyre CC, et al. Tractography activation patterns in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex suggest better clinical responses in OCD DBS. Neuroprosthetics. 2016;9:519.

Baldermann JC, Melzer C, Zapf A, Kohl S, Timmermann L, Tittgemeyer M, et al. Connectivity profile predictive of effective deep brain stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2019;85:735–43.

Barcia JA, Avecillas-Chasín JM, Nombela C, Arza R, Albea JG-, Pineda J-Á, et al. Personalized striatal targets for deep brain stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Brain Stimulat. 2018; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2018.12.226.

Mosley PE, Windels F, Morris J, Coyne T, Marsh R, Giorni A, et al. A randomised, double-blind, sham-controlled trial of deep brain stimulation of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis for treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:1–17.

Smith AH, Choi KS, Waters AC, Aloysi A, Mayberg HS, Kopell BH, et al. Replicable effects of deep brain stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Brain Stimul. 2021;14:1–3.

Bouwens van der Vlis TAM, Ackermans L, Mulders AEP, Vrij CA, Schruers K, Temel Y, et al. Ventral capsule/ventral striatum stimulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder: toward a unified connectomic target for deep brain stimulation? Neuromodulation. 2021; https://doi.org/10.1111/ner.13339.

Baldermann JC, Schüller T, Kohl S, Voon V, Li N, Hollunder B, et al. Connectomic deep brain stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2021; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2021.07.010.

Haber SN, Yendiki A, Jbabdi S. Four deep brain stimulation targets for obsessive-compulsive disorder: Are they different? Biol Psychiatry. 2020;S000632232031773X.

Wood J, Ahmari SE. A framework for understanding the emerging role of corticolimbic-ventral striatal networks in OCD-associated repetitive behaviors. Front Syst Neurosci. 2015;9:171.

Burguière E, Monteiro P, Feng G, Graybiel AM. Optogenetic stimulation of lateral orbitofronto-striatal pathway suppresses compulsive behaviors. Science. 2013;340:1243–6.

Heilbronner SR, Rodriguez-Romaguera J, Quirk GJ, Groenewegen HJ, Haber SN. Circuit based cortico-striatal homologies between rat and primate. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80:509–21.

Makris N, Rathi Y, Mouradian P, Bonmassar G, Papadimitriou G, Ing WI, et al. Variability and anatomical specificity of the orbitofrontothalamic fibers of passage in the ventral capsule/ventral striatum (VC/VS): precision care for patient-specific tractography-guided targeting of deep brain stimulation (DBS) in obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Brain Imaging Behav. 2016;10:1054–67.

Liebrand LC, Caan MWA, Schuurman PR, van den Munckhof P, Figee M, Denys D, et al. Individual white matter bundle trajectories are associated with deep brain stimulation response in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Brain Stimulat. 2018; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2018.11.014.

Howell B, McIntyre CC. Analyzing the tradeoff between electrical complexity and accuracy in patient-specific computational models of deep brain stimulation. J Neural Eng. 2016;13:036023.

Poldrack RA, Huckins G, Varoquaux G. Establishment of best practices for evidence for prediction: a review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77:534–40.

Grzenda A, Kraguljac NV, McDonald WM, Nemeroff CB, Torous J, Alpert JE, et al. Evaluating the machine learning literature: a primer and user’s guide for psychiatrists. Am J Psychiatry. 2021; https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20030250.

Lo A, Chernoff H, Zheng T, Lo S-H. Why significant variables aren’t automatically good predictors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:13892–7.

Widge AS, Bilge MT, Montana R, Chang W, Rodriguez CI, Deckersbach T, et al. Electroencephalographic biomarkers for treatment response prediction in major depressive illness: a meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176:44–56.

Woo C-W, Chang LJ, Lindquist MA, Wager TD. Building better biomarkers: brain models in translational neuroimaging. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:365–77.

Coenen VA, Schlaepfer TE, Varkuti B, Schuurman PR, Reinacher PC, Voges J, et al. Surgical decision making for deep brain stimulation should not be based on aggregated normative data mining. Brain Stimul Basic Transl Clin Res Neuromodulation. 2019;12:1345–8.

McLaughlin N, Dougherty DD, Eskandar EN, Ward HE, Foote KD, Malone Jr DA, et al. Double blind randomized controlled trial of deep brain stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder: clinical trial design. Contemp Clin Trials. 2021;22:100785.

reckbo, Tashrif Billah, Isaiah Norton. Pnlbwh/Pnlpipe: Easy Install and Multiprocessing. Zenodo. 2019; https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3270927.

Malcolm JG, Shenton ME, Rathi Y. Filtered multitensor tractography. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2010;29:1664–75.

Reddy CP, Rathi Y . Joint multi-fiber NODDI parameter estimation and tractography using the unscented information filter. Front Neurosci. 2016;10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2016.00166.

Gong S, Zhang F, Norton I, Essayed WI, Unadkat P, Rigolo L, et al. Free water modeling of peritumoral edema using multi-fiber tractography: Application to tracking the arcuate fasciculus for neurosurgical planning. PLoS ONE. 2018; 13. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0197056.

Liao R, Ning L, Chen Z, Rigolo L, Gong S, Pasternak O, et al. Performance of unscented Kalman filter tractography in edema: Analysis of the two-tensor model. NeuroImage Clin. 2017;15:819–31.

Zhang F, Wu Y, Norton I, Rigolo L, Rathi Y, Makris N, et al. An anatomically curated fiber clustering white matter atlas for consistent white matter tract parcellation across the lifespan. NeuroImage. 2018;179:429–47.

Chen Z, Tie Y, Olubiyi O, Rigolo L, Mehrtash A, Norton I, et al. Reconstruction of the arcuate fasciculus for surgical planning in the setting of peritumoral edema using two-tensor unscented Kalman filter tractography. NeuroImage Clin. 2015;7:815–22.

Chaturvedi A, Luján JL, McIntyre CC. Artificial neural network based characterization of the volume of tissue activated during deep brain stimulation. J Neural Eng. 2013;10:056023.

Butson CR, McIntyre CC. Role of electrode design on the volume of tissue activated during deep brain stimulation. J Neural Eng. 2006;3:1–8.

O’Donnell LJ, Westin C-F. Automatic tractography segmentation using a high-dimensional white matter atlas. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2007;26:1562–75.

O’Donnell LJ, Wells WM, Golby AJ, Westin C-F. Unbiased groupwise registration of white matter tractography. In: Ayache N, Delingette H, Golland P, Mori K, editors. Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2012, vol. 7512. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2012; pp 123-30.

Couronné R, Probst P, Boulesteix A-L. Random forest versus logistic regression: a large-scale benchmark experiment. BMC Bioinforma. 2018;19:270.

Chawla NV, Bowyer KW, Hall LO, Kegelmeyer WP. SMOTE: synthetic minority over-sampling technique. J Artif Intell Res. 2002;16:321–57.

Tyagi H, Apergis-Schoute AM, Akram H, Foltynie T, Limousin P, Drummond LM, et al. A randomised trial directly comparing ventral capsule and anteromedial subthalamic nucleus stimulation in obsessive compulsive disorder: clinical and imaging evidence for dissociable effects. Biol Psychiatry. 2019;85:726–34.

Widge AS, Licon E, Zorowitz S, Corse A, Arulpragasam AR, Camprodon JA, et al. Predictors of hypomania during ventral capsule/ventral striatum deep brain stimulation. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;28:38–44.

Denys D, Graat I, Mocking R, de Koning P, Vulink N, Figee M, et al. Efficacy of deep brain stimulation of the ventral anterior limb of the internal capsule for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a clinical cohort of 70 patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177:265–71.

Smith GCS, Seaman SR, Wood AM, Royston P, White IR. Correcting for optimistic prediction in small data sets. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180:318–24.

Storch EA, Rasmussen SA, Price LH, Larson MJ, Murphy TK, Goodman WK. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Yale–Brown obsessive-compulsive scale—second edition. Psychol Assess. 2010;22:223.

Widge AS, Dougherty DD. Managing patients with psychiatric disorders with deep brain stimulation. In: Marks Jr. WJ, editor. Deep Brain Stimulation Management, 2nd ed. 2015; Cambridge: New York: Cambridge University Press.

van Westen M, Rietveld E, Bergfeld IO, Koning P, de, Vullink N, Ooms P, et al. Optimizing deep brain stimulation parameters in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Neuromodulation Technol Neural Interface. 2021;24:307–15.

Mantione M, Nieman DH, Figee M, Denys D. Cognitive–behavioural therapy augments the effects of deep brain stimulation in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Psychol Med. 2014;44:3515–22.

van Westen M, Rietveld E, Denys D. Effective deep brain stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder requires clinical expertise. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2294.

Burguière E, Monteiro P, Mallet L, Feng G, Graybiel AM. Striatal circuits, habits, and implications for obsessive–compulsive disorder. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2015;30:59–65.

Garnaat SL, Greenberg BD, Sibrava NJ, Goodman WK, Mancebo MC, Eisen JL, et al. Who qualifies for deep brain stimulation for OCD? Data from a naturalistic clinical sample. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;26:81–86.

Duchin Y, Shamir RR, Patriat R, Kim J, Vitek JL, Sapiro G, et al. Patient-specific anatomical model for deep brain stimulation based on 7 Tesla MRI. PloS ONE. 2018;13:e0201469.

Button KS, Ioannidis JPA, Mokrysz C, Nosek BA, Flint J, Robinson ESJ, et al. Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:365–76.

Menchón JM, Real E, Alonso P, Aparicio MA, Segalas C, Plans G, et al. A prospective international multi-center study on safety and efficacy of deep brain stimulation for resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:1234–47.

Greenberg B, Gabriels L, Malone D, Rezai A, Friehs G, Okun M, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral internal capsule/ventral striatum for obsessive-compulsive disorder: worldwide experience. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:64–79.

Nuttin B, Cosyns P, Demeulemeester H, Gybels J, Meyerson B. Electrical stimulation in anterior limbs of internal capsules in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Lancet. 1999;354:1526.

Basu I, Yousefi A, Crocker B, Zelmann R, Paulk AC, Peled N, et al. Closed loop enhancement and neural decoding of human cognitive control. Nat Biomed Eng. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.24.059964.

Widge AS, Zorowitz S, Basu I, Paulk AC, Cash SS, Eskandar EN, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the internal capsule enhances human cognitive control and prefrontal cortex function. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1536.

Gruner P, Pittenger C. Cognitive inflexibility in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuroscience. 2017;345:243–55.

Abramovitch A, Abramowitz JS, Mittelman A. The neuropsychology of adult obsessive–compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:1163–71.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH grants R03MH111320 (ASW, CCM, DDD), UH3NS100548 (ASW, DDD), R01MH111917 (ASW, DDD, NM, YR), U01MH076179 (BDG), P20GM130452 (NCM, BDG), K23MH100607 (NCM), K24MH116366 (NM), and P50MH106435 (NCM, BDG). ASW further acknowledges support from the MnDRIVE Brain Conditions and Minnesota Medical Discovery Team – Addictions initiatives. All opinions and conclusions herein are those of the authors. They do not represent the views or official policy of any public or private funding body.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ASW, DDD, YR, NM, and CCM designed the research and obtained funding. BDG and NCRM contributed unpublished data; BDG also designed and obtained funding for the clinical trial that produced the majority of the data reported herein. AMN and CCM contributed unpublished software (a customized version of StimVision) that was central to the analysis. FZ, AG, GP, PW-B, MT, SP, LO, NM, and YR performed the tractographic and field modeling analyses. ASW performed all statistical analyses. ASW wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, with substantial textual contributions from AMN, CCM, and YR, followed by editing from NCRM, BDG, NM, and DDD. All authors had the opportunity to review, comment on, and approve the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

ASW and DDD have received research funding, device donations, and honoraria from Medtronic, which manufactured the DBS devices used in patients’ clinical care. Medtronic had no financial or technical role in this study. ASW and CCM have multiple patents and patent filings in the area of deep brain stimulation, including methods for optimizing/customizing stimulation parameters. CCM is a paid consultant for Boston Scientific Neuromodulation, receives royalties from Hologram Consultants, Neuros Medical, Qr8 Health, and is a shareholder in the following companies: Hologram Consultants, Surgical Information Sciences, CereGate, Autonomic Technologies, Cardionomic, and Enspire DBS. All other authors affirm no related financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Widge, A.S., Zhang, F., Gosai, A. et al. Patient-specific connectomic models correlate with, but do not reliably predict, outcomes in deep brain stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacol. 47, 965–972 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-021-01199-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-021-01199-9

This article is cited by

-

Closing the loop in psychiatric deep brain stimulation: physiology, psychometrics, and plasticity

Neuropsychopharmacology (2024)

-

Tractography-based versus anatomical landmark-based targeting in vALIC deep brain stimulation for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder

Molecular Psychiatry (2022)

-

Connectomic approaches to deep brain stimulation for OCD

Neuropsychopharmacology (2022)