Abstract

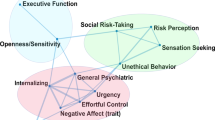

The neurobiological traits that confer risk for addictions remain poorly understood. However, dopaminergic function throughout the prefrontal cortex, limbic system, and upper brainstem has been implicated in behavioral features that influence addiction vulnerability, including poor impulse control, and altered sensitivity to rewards and punishments (i.e., externalizing features). To test these associations in humans, we measured type-2/3 dopamine receptor (DA2/3R) availability in youth at high vs. low risk for substance use disorders (SUDs). In this study, N = 58 youth (18.5 ± 0.6 years) were recruited from cohorts that have been followed since birth. Participants with either high (high EXT; N = 27; 16 F/11 M) or low pre-existing externalizing traits (low EXT; N = 31; 20 F/11 M) underwent a 90-min positron emission tomography [18F]fallypride scan, and completed the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11), Substance Use Risk Profile scale (SURPS), and Sensitivity to Punishment (SP) and Sensitivity to Reward (SR) questionnaire. We found that high vs. low EXT trait participants reported elevated substance use, BIS-11, SR, and SURPS impulsivity scores, had a greater prevalence of psychiatric disorders, and exhibited higher [18F]fallypride binding potential (BPND) values in prefrontal, limbic and paralimbic regions, even when controlling for substance use. Group differences were not evident in midbrain dopamine cell body regions, but, across all participants, low midbrain BPND values were associated with low SP scores. Together, the results suggest that altered DA2/3R availability in terminal extra-striatal and dopamine cell body regions might constitute biological vulnerability traits, generating an EXT trajectory for addictions with and without co-occurring alterations in punishment sensitivity (i.e., an internalizing feature).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In many societies, adolescent substance use is the norm. Despite this, only some will develop a substance use disorder (SUD). The best characterized vulnerability traits are diverse externalizing (EXT) features [1, 2], including impulsivity and altered responses to rewards and punishments [3]. These features manifest early and continue throughout adolescence, increasing the probability of developing SUDs and comorbid psychiatric problems [4, 5].

The neurobiology mediating these vulnerability features is not well understood, but both increases and decreases in mesocorticolimbic dopamine (DA) function have been implicated. Most of this work has focused on the striatum [4, 6, 7], but there is growing interest in the contributions of extra-striatal regions. In laboratory animals, prefrontal DA transmission influences temporal discounting [8,9,10] and most elements of executive function [11]. Dopamine transmission in the amygdala and anterior cingulate, in comparison, increases the willingness to sustain effort to obtain rewards [8, 9], hippocampal DA transmission fosters the formation and activation of emotionally charged memories [12], and DA release in the ventral prelimbic cortex tracks changes in reward rate probability [13].

In humans, research on SUD risk traits in relation to extra-striatal DA has focused on type-2/3 DA receptors (DA2/3Rs). A cohesive picture has yet to emerge, but a few relatively small neuroimaging studies raise the possibility that individual differences in impulsivity covary positively with DA2/3R availability in the temporal cortex and thalamus [14], while amygdalar DA2/3R availability influences emotion regulation [15], and elevated DA2/3R levels in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) has been associated with larger amygdala responses to unpleasant stimuli [16]. Negative correlations, in comparison, have been reported between midbrain cell body region DA2/3R availability and impulsivity-related personality traits [7], drug cue-induced drug craving [17], and striatal DA release [7, 17]. These latter effects have been proposed to reflect inhibitory feedback from somatodendritic autoreceptors on DA cells that project to the striatum [7, 17]. Indeed, in humans, midbrain DA2/3 autoreceptors appear to be largely restricted to mesostriatal neurons [17, 18].

To better test the hypothesized relation between extra-striatal DA2/3R availability and pre-existing SUD risk traits, we conducted [18F]fallypride positron emission tomography (PET) scans in a relatively large sample of 18–20-year-old youth recruited from research participants who have been characterized and followed since birth, and who exhibited high vs. low EXT traits during early adolescence (between the ages of 10 and 16 years). We predicted that the high vs. low SUD risk participants, based on EXT traits, would have lower [18F]fallypride nondisplaceable binding potential (BPND) values in the midbrain, and elevated BPND values in the PFC and limbic and paralimbic terminal regions, particularly in the amygdala. Individual differences in DA2/3R availability would be associated with EXT features, including impulsivity, other substance use risk traits, and sensitivity to reward and punishment.

Methods and materials

Participants

We recruited transitional age youth (18–20 year) from: (i) the “Quebec Longitudinal Study of Child Development” (QLSCD; 31 participants from the 572 born in 1996 [19], and 22 from 2120 born in 1997–1998 [20]) and (ii) the “Quebec Newborn Twin Study” (QNTS; 5 participants from 662 twin pairs born in 1995–1997 [21]; only one sibling per pair tested). All participants lived in the area of Montreal and Quebec City, and had been followed since birth.

Eligibility was based on questions from developmentally appropriate behavior questionnaires [22,23,24], which were used to develop the “social behavior questionnaire” [25]. A subset of the scores, from the first wave of QLSCD study members (N = 242), was summed to form an aggregate EXT trait score; i.e., mean scores for the subscales hyperactivity, impulsivity, oppositional behavior, nonaggressive behavioral problems and aggression (proactive, indirect, reactive) [25]. Mean EXT scores during early adolescence correlated with those obtained earlier in life (1–5 and 6–10 years) and predicted substance use at age 16 years [25]. EXT cut-off scores representing individuals that fell in the top and bottom 30%, as established in the first wave of study members, were then applied to the entire sample of participants (i.e., total QLSCD and QNTS samples) with a minimum of two assessments between ages 10 and 16 years. These individuals were considered at high vs low risk for substance use problems, respectively [25], and were invited to participate in the neuroimaging study. The final [18F]fallypride imaging sample consisted of 31 low-risk (20 F/11 M) and 27 high-risk trait youth (N = 27, 16 F/11 M; Table 1).

Screening and clinical information

Cohort members who expressed interest in the present study were telephone screened. Eligible participants were then invited for in-person assessments using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 [26]. All provided drug and alcohol use histories using the Timeline Follow-Back Method [27] and Alcohol Use Disorders Screening Test (AUDIT) [28], supplementing data that had been collected prospectively during annual interviews between ages 10 and 16 years. Participants also completed the Substance Use Risk Profile Scale (SURPS) [29], Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11) [30], and Sensitivity to Punishment (SP) and Sensitivity to Reward (SR) Questionnaire (SPSRQ) [31]. The scales have demonstrated validity in adolescents and young adults, and have acceptable test-retest reliability [32,33,34]. Ethics approval was granted by the McGill University and Sainte-Justine University Hospital Research Ethics Boards, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Participants were excluded if they were currently taking psychotropic medication, had magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or PET contraindications or significant medical conditions (Table 1). Females were excluded if they were pregnant (urine test: Biostrip HCG, Innovatek Medical Inc., Delta, BC, Canada).

Urine drug screens (Express Diagnostics, MN, USA) were obtained prior to PET scans, and participants were excluded if they tested positive for drugs (amphetamine, benzodiazepines, buprenorphine, cocaine, 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine, methamphetamine, methadone, opioids) other than tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Five participants tested positive for THC but were not acutely intoxicated, and were included in the study (all in the high EXT group; Table 1). Participants were asked to refrain from caffeine for >4 h, nicotine for >12 h (one participant abstained for only 6.5 h; excluding this individual did not alter our results, presented below), and alcohol for >24 h prior to their PET scan. A breathalyser test ensured alcohol abstinence (BACtrack S80, KHN Solutions LLC, CA, USA). To control for gonadal hormone fluctuations, females who were not using a hormonal contraceptive were scanned during their follicular phase (days 1–10, self-report); all participants were scanned within a narrow time window (13h00–16h30).

Neuroimaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) acquisition

MRI scans were acquired using a 3 T Siemens Trio TIM scanner (McConnell Brain Imaging Centre, Montreal Neurological Institute) with a Magnetization Prepared Rapid Acquisition sequence (slice: 1 mm; TR: 2300 ms, TE: 3.42 ms, flip angle: 9°, FOV: 256 mm, Matrix: 256 × 256).

PET scans were acquired with a high-resolution research tomograph (HRRT, CTI/Siemens). Following cannula insertion into the left antecubital vein for tracer administration, a 6-min 137Cs transmission scan was obtained for attenuation correction. The [18F]fallypride tracer (prepared as previously described [17]) was administered as a 1-min intravenous bolus, with emission scans acquired concurrently in list mode over 90-min (participants were instructed to remain awake). The average [18F]fallypride dose was 3.33 ± .20 mCi (3.1–3.7 mCi; ~125MBq), and specific activity was 6929.2 ± 6688 GBq/µmol (no group differences, p > 0.10). Previous work indicates that this corresponds to an effective dose equivalent of [18F]fallypride of ~0.021 mSv/MBq [35], thus, participants were exposed to ~2.6 mSv, on average. There were no group differences in PET tracer dose (low EXT: 3.28 ± 0.23 mCi [121.4MBq]; high EXT: 3.38 ± 0.14 mCi [125.06MBq]). Prior to the [18F]fallypride scan, all participants had a 60-min PET scan with a [11C]-labeled tracer [36].

PET images were reconstructed using the Ordinary Poisson Ordered Subset Expectation Maximization reconstruction algorithm (10 iterations, 16 subsets). This included correction for nonuniformities, attenuation, scattered and random coincidences, and motion. To reduce partial volume effects, resolution modeling using the point spread function was implemented in image reconstruction. Motion correction was based on a data-driven motion estimation and correction method that estimates rigid-body motion between dynamic frames [37]. Reconstructed image frames consisted of 256 × 256 × 207 voxels (voxel length = 1.21875 mm).

MRI and PET analyses

MRIs were pre-processed with the CIVET 2.0.0 pipeline (wiki.bic.mni.mcgill.ca/ServicesSoftware/CIVET), which included correction for image intensity and nonuniformity, and nonlinear and linear transformations to standardized stereotaxic space using the ICBM template [38]. Normalized images were then classified into white matter, gray matter and cerebral spinal fluid, and segmented using a probabilistic atlas based approach (Automatic Nonlinear Image Matching and Anatomical Labeling [ANIMAL]) [39].

Regions of interest (ROIs) were defined on each individual’s CIVET-processed MRI scans using standardized masks (defined on the MNI ICBM-152 template, and registered to each participant’s MRI via linear and nonlinear transformations). Frontal ROIs were defined using ANIMAL segmentation, and included the gray matter of bilateral superior and middle frontal gyri (i.e., dorsolateral PFC aspects), the medial orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and medial frontal gyri (i.e., medial PFC aspects); these regions were similar to those used in another study by our group assessing extra-striatal DA2/3R availability [17]. Limbic and paralimbic ROIs (amygdala, hippocampus, insula) were derived from the Talairach atlas [40] using the Talairach Deamon and PickAtlas software. Finally, a whole midbrain ROI (substantia nigra, ventral tegmental area) was derived from a mask provided by Dr. Adcock’s Laboratory at Duke University (MNI ICBM-152 space) [41]. Striatal DA2/3R expression was not measured as scans longer than 90 min are required for this purpose [42].

ROI masks (Supplementary Fig. 1), were applied to each summed PET image using nonlinear coregistration. Time-activity curves were extracted from each ROI in native PET space using tools developed by the Turku PET Centre (http://www.turkupetcentre.net/). BPND values (i.e., equilibrium ratio of specifically bound to nondisplaceable radioligand in tissue) were derived from ROIs, averaged across the hemispheres, using the simplified reference tissue model [43], with cerebellar gray matter as the reference region.

Statistical analyses

Demographic and clinical data

Groups (high/low EXT) were compared on pertinent variables with univariate analyses of variance (ANOVAs) or Chi-Square tests (Table 1). Multivariate ANOVAs were carried out to assess group differences on the SURPS, BIS-11, and SPSRQ.

[18F]Fallypride BPND values

A repeated-measures analysis of covariance (rmANCOVA) was conducted for DA terminal regions with group (high/low EXT) as the between-subject factor and region as within subject-factors (superior frontal gyri, middle frontal gyri, medial frontal gyri, OFC, amygdala, hippocampus, insula). A univariate ANCOVA with group (high/low EXT) as the between-subject factor was carried out for the midbrain. The following covariates were included: number of lifetime cannabis occasions, number of lifetime noncannabis drug occasions, AUDIT scores, and current smoking status (yes/no). These covariates were selected to control for drug use, which may affect [18F]fallypride BPND values, and other DA activity indices [44, 45]. Tests of normality of the ROI BPND value residuals were assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. If normality was violated, BPND values were examined for outliers, which were removed (>±3 SD group mean). Greenhouse–Geisser corrections were applied when sphericity was violated (p < 0.05).

Correlations between [18F]Fallypride BPND and clinical measures

Spearman correlations were carried out between variables of interest (SURPS [four factors], BIS [three factors], SPSRQ [two factors]) and ROI BPND values. Significance was set to p < 0.0007 for the correlations (p = 0.05/72 [9 questionnaire factors × 8 ROIs]). Partial correlations were secondarily carried out for significant correlations controlling for AUDIT scores, lifetime drug use occasions (all drugs, apart from cannabis, tobacco, alcohol), lifetime cannabis use occasions, and current tobacco smoking status. Correlations were conducted for the entire sample and per group (outliers removed; Table 2).

Results

Demographic and clinical data

The high vs. low-risk groups were well-matched on family income (above/below 39,999CDN/year, data not shown), age and sex; by design, they differed on EXT scores [F(1,56) = 262.30, p < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.82]. They also differed on EXT-related features. Compared with the low EXT group, high EXT participants had elevated BIS-11 [Wilk’s Lambda = 5.82 (df = 3,52), p = 0.002; partial η2 = 0.25], SPSRQ [Wilk’s Lambda = 3.41 (df = 2,53), p = 0.04; partial η2 = 0.11] and SURPS scores [Wilk’s Lambda = 3.22 (df = 4,51), p = 0.02; partial η2 = 0.20] (Table 1).

High EXT participants also exhibited evidence of more problematic drinking, as indexed by higher AUDIT scores [F(1,56) = 4.64, p = 0.036; partial η2 = 0.076] and more occasions of binge drinking [F(1,57) = 5.65, p = 0.021, η2 = 0.09], a greater number of lifetime cannabis use occasions [F(1,56) = 7.48, p = 0.008; partial η2 = 0.12], more use of drugs other than alcohol, tobacco and cannabis [Chi = 5.83, (df = 1,58), p = 0.004], and an elevated history of psychiatric disorders including mild SUDs, mood and anxiety disorders [Chi = 15.90, (df = 1,58), p < 0.001] (Table 1).

[18F]Fallypride BPND values

The rmANCOVA for BPND values in DA terminal regions yielded a main effect of group [F(1,51) = 4.60, p = 0.025; partial η2 = .10] and region [F(2.31,106.17) = 328.44, p < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.88]. The effect of region reflected highest values in the amygdala followed by the insula, hippocampus, OFC, middle frontal gyrus, medial frontal gyrus, and superior frontal gyrus (Figs. 1, 2; Table 2). The effect of group reflected higher values in high EXT participants. A group × region interaction effect was evident at the trend level [F(2.31,106.17) = 2.55, p = 0.074; partial η2 = 0.053]. Follow-up comparisons confirmed higher adjusted BPND in the high vs. low EXT group in all regions (ps < 0.05) except for the OFC and hippocampus, where the effects were less compelling (ps > 0.30). Inclusion of a positive THC screen (N = 5) as an additional covariate did not change the pattern of terminal region BPND results (main effect of group: p = 0.009; partial η2 = 0.15); the same was true of including the presence of past or current SUD as an additional covariate (N = 5; main effect of group: p = 0.011; partial η2 = 0.13). Including both a positive THC screen and past or current SUD as additional covariates in the analyses strengthened the main group effect [F(1,41) = 9.02, p = 0.005; partial η2 = 0.18, generally considered a medium effect size]; the group × region interaction continued to be significant at the trend level (p = 0.077), Greenhouse–Geisser corrected.

There was no effect of group for midbrain BPND values [F(1,48) = 1.90, p = 0.18; partial η2 = 0.038; Table 2]. The addition of a positive THC screen (N = 5; p = 0.18), past or current SUD (N = 5, p = 0.13) or both features (p = 0.13) as additional covariates did not reveal a main effect of group on midbrain BPND values. Raw BPND values (i.e., means unadjusted by the inclusion of covariates) per ROI are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Correlations between [18F]Fallypride BPND and clinical measures

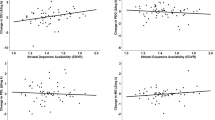

Across the whole sample, there was a positive correlation between midbrain BPND values and SP scores (rho = 0.51, p = 0.00014, N = 52; partial correlation: r = 0.51, p = 0.0002, N = 46; Fig. 3). When the high and low EXT groups were analyzed separately, the correlations did not survive our conservative statistical correction, but the same associations were evident at the trend level (low EXT: rho = 0.54, p = 0.003; high EXT: rho = 0.43, p = 0.046). Exploratory analyses yielded a negative correlation between midbrain BPND values with the SR:SP ratio (rho = −0.47, p = 0.00042, N = 52; partial correlation: r = −0.37, p = 0.010, N = 46; Fig. 3). No other correlations between variables of interest (SURPS, BIS, SPSRQ), and BPND values were significant at our threshold of p < 0.0007.

Upper: Correlation between midbrain BPND values and Sensitivity to Punishment scores across the entire cohort (rho = 0.51, p = 0.00014, N = 52; circles: high EXT; diamonds: low EXT). Lower: Correlation between midbrain BPND values and Sensitivity to Reward:Punishment score ratios across the entire cohort (rho = −0.47, p = 0.00042, N = 52; circles: high EXT; diamonds: low EXT).

Discussion

We measured extra-striatal DA2/3R availability in well-characterized youth who had been followed since birth. Participants were tested during their transition years to adulthood, a period of significant fronto-cortical pruning [46] and mesocortical DA pathway expansion [47]. It is also the developmental stage when drug and alcohol experimentation is most likely to escalate to problematic use. As expected, participants at elevated risk for SUDs, based on higher pre-existing EXT traits, had more lifetime occasions of drug use and binge drinking, a denser history of lifetime psychiatric issues, and higher AUDIT, Impulsivity, BIS-11 and SR scores than those with low EXT traits. More novel is the finding that the high-risk participants exhibited elevated [18F]fallypride BPND values throughout the PFC and limbic and paralimbic regions, even after controlling for drug and alcohol use. These widespread increases in terminal region DA2/3R availability could reflect low levels of competing extracellular DA or greater extra-striatal DA2/3R density. Since reductions in extracellular DA do not yield pronounced effects on extra-striatal [18F]fallypride BPND values [48], the latter interpretation may be more plausible. Group differences were not evident in the midbrain cell body region, but, across the entire sample, midbrain DA2/3R availability correlated positively with SP scores.

Individual differences in cortical DA projections might play particularly important roles in the development of SUD susceptibility related phenotypes [47]. Cortical DA transmission sustains neural activity, facilitating the planning of complex behavioral sequences, impulse control, and reward processing [11, 17]. Though most attention has been paid to cortical DA1 receptors, accumulating evidence indicates that DA2/3Rs also modulate cortical cell excitability, influencing perseverative behaviors and behavioral inhibition, perhaps through actions on subcortical projection sites [11, 49]. The elevated cortical DA2/3R availability in our high-risk youth might aggravate susceptibility to these maladaptive behaviors, as greater PFC DA2/3R-mediated neurotransmission has been associated with impulsive behaviors in laboratory animals [50].

Group differences were also observed in limbic and paralimbic regions. The elevated amygdalar DA2/3R availability in high EXT participants may lead to difficulties in emotion regulation [15] and altered appetitive responses to cues associated with drugs and other rewards [51]. However, the contribution of these DA2/3Rs might be complex: in laboratory animals, their stimulation decreases impulsive behaviors and incentive motivational effects [52, 53], while also increasing cocaine-seeking behaviors [54]. The insula is increasingly implicated in diverse addiction-related processes, including emotional aspects of risky decision making [55], and drug craving [56]. Indeed, compared with healthy controls, people with an alcohol use disorder have been reported to exhibit lower baseline insular DA2/3R BDND values [57].

The mechanism by which the high-risk, high EXT participants came to have elevated DA2/3R availability is unknown, and cannot be answered from our study alone. However, it is unlikely to reflect diminished competition from extracellular DA since experimentally induced decreases in DA release have minimal effects on [18F]fallypride binding [48]. One possibility is that increased extra-striatal DA2/3R levels reflect an adaptation to chronically low extracellular DA levels. Alternatively, the greater density of DA2/3R in high EXT individuals may be an inherited feature; indeed, the prior evidence of genetic predispositions to low DA2 receptor function in addiction susceptible populations has now been shown to reflect biased allele frequencies in healthy control samples [58]. In either scenario, the widespread increases in DA2/3Rs could lead to elevated DA2/3R-mediated signaling, disrupting better calibrated reward processing [59, 60].

The [18F]fallypride BPND values in our low-risk participants (see unadjusted BPND values in Supplementary Table 1) were similar to what have been previously found in a large sample of healthy volunteers [61]. However, the BPND values in our adolescent sample overall were generally higher than what has been observed in middle-aged adults [61], consistent with DA2 receptor expression declines with increased age [61, 62]. Of potentially greater importance, the [18F]fallypride BPND values in our high-risk participants and age-matched controls [61] were higher than what we have found in people with a current moderate to severe SUD [17, 51], particularly in limbic and paralimbic regions (Supplementary Table 1). It remains unknown whether a switch from high to low DA2/3R availability occurs in high EXT individuals who transition to a SUD, but this is plausible given that a compensatory down-regulation in receptor density has been reported in nonhuman primates following frequent drug-induced surges in extracellular DA [63]. These hypothesized decrements have been proposed to contribute to the diminished incentive value of nondrug rewards and the progressive narrowing of interests [4, 64].

The last major finding in the present study was the relation between sensitivity to punishment and midbrain DA2/3R availability, plausibly reflecting the degree of somatodendritic autoreceptor-mediated inhibitory feedback [7, 17, 18]. Of note, lower striatal DA reactivity, which has been linked to increased levels of midbrain D2/3 autoreceptors, has been associated with higher trait anxiety [65]. The absence of a group difference in midbrain DA2/3R availability highlights how the EXT risk pathway can be combined with varying features, either additional impulsivity-related traits (e.g., low punishment and high reward sensitivity) or anxious, internalizing traits (e.g., high punishment sensitivity). Both might be associated with elevated terminal region DA2/3R availability yet high vs. low mesostriatal DA reactivity, respectively.

Strengths and limitations

The current study has multiple strengths. This includes the use of high-resolution PET imaging in a relatively large sample (for PET studies) of well-characterized participants with a narrow age range prospectively followed from birth. Nevertheless, some limitations exist. First, the imaging data are cross-sectional, and we do not know whether they will identify future substance use problems. Second, our PET scans lasted 90-min, which is suitable for measuring DA2/3R availability in the targeted extra-striatal regions but not the striatum, which requires a longer scan [42]. This noted, a large body of work indicates that striatal DA2/3R availability is not decreased (and tends to be increased) in people at familial risk for SUDs [66]. Here, we report, to our knowledge, the first evidence of altered extra-striatal DA2/3R availability in transitional aged youth at risk for SUDs. Third, some have interpreted elevated DA2/3R availability as a protective feature [67, 68]. The elevated DA2/3R availability observed in the current study might also reflect this. However, the prospectively documented risk traits and behaviors, including substance use problems already, argues against the protection hypothesis, and more strongly favors the risk hypothesis. Fourth, group differences were seen in terminal region DA2/3R availability, but the individual differences in BPND did not significantly correlate with clinical features or other behavioral traits. This might indicate that complex behavioral effects of extra-striatal terminal region DA transmission emerge from cumulative actions at multiple receptors. In comparison, midbrain DA2/3R availability correlated with SP scores, raising the possibility that these putative autoreceptors are more closely related to overall mesostriatal DA function and mesostriatal DA-related behaviors [7, 17, 18]. Fifth, sex was imbalanced in both EXT groups. Exploratory analyses of the BPND data suggest that the effect of group might be stronger in males than females, but there was neither a main effect of sex nor a sex by risk group interaction (data not shown). Given the relatively small subsamples, it is possible that sex-specific effects exist and should be further tested in future work. Finally, individuals with high EXT traits had a denser history of mental health problems. However, the inclusion of any past or present psychiatric illness (N = 14) as an additional covariate did not alter the group differences in BPND values (data not shown); the same is true for the addition of current SUDs (N = 5; mainly cannabis related [N = 4]). Indeed, the presence of clinically relevant symptoms prior to the onset of SUDs has been considered an expression of the developing risk pathway [1, 2, 5].

Funding and disclosure

This work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR): MOP-133537 (ML, JRS, CB, MB), MOP-44072 (JRS), MOP-97910 (JRS, SP); from the Fonds de Recherche du Quebec (FRQ)-Santé: 981055, 991027 (JRS), 35282 (NCR); FRQ-Société et Culture: 2002-RS-79238, 2009-RG-124779 (JRS, MB); from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC): 410–99–1048, 839–2000–1008 (JRS, MB). The QLSCD cohort born in 1997–1998 is led by the Institut de la Statistique du Québec, in collaboration with several departments and agencies of the Government of Quebec and collaborating researchers, including authors of this article. Project completion with QLSCD participants was authorized by the QLSCD Steering Committee. None of the authors have conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

Kendler KS, Lönn SL, Maes HH, Lichtenstein P, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. A Swedish population-based multivariate twin study of externalizing disorders. Behav Genet. 2016;46:183–92.

Krueger RF, Tackett JL. Personality and psychopathology: working toward the bigger picture. J Pers Disord. 2003;17:109–28.

Kotov R, Ruggero CJ, Krueger RF, Watson D, Yuan Q, Zimmerman M. New dimensions in the quantitative classification of mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:1003–11.

Leyton M, Vezina P. Dopamine ups and downs in vulnerability to addictions: a neurodevelopmental model. Trends Pharm Sci. 2014;35:268–76.

Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Moss HB, Li TK, Grant BF. Gender differences in the relationship of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology to alcohol dependence: likelihood, expression and course. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112:9–17.

Leyton M, Boileau I, Benkelfat C, Diksic M, Baker G, Dagher A. Amphetamine-induced increases in extracellular dopamine, drug wanting, and novelty seeking: a PET/[11C]raclopride study in healthy men. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:1027–35.

Buckholtz JW, Treadway MT, Cowan RL, Woodward ND, Li R, Ansari MS, et al. Dopaminergic network differences in human impulsivity. Science. 2010;329:532.

Winstanley CA, Theobald DEH, Cardinal RN, Robbins TW. Contrasting roles of basolateral amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex in impulsive choice. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4718–22.

Floresco SB, Ghods-Sharifi S. Amygdala-prefrontal cortical circuitry regulates effort-based decision making. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:251–60.

Kheramin S, Body S, Ho MY, Velázquez-Martinez DN, Bradshaw CM, Szabadi E, et al. Effects of orbital prefrontal cortex dopamine depletion on inter-temporal choice: a quantitative analysis. Psychopharmacol. 2004;175:206–14.

Arnsten AFT, Vijayraghavan S, Wang M, Gamo NJ, Paspalas CD. Dopamine’s influence on prefrontal cortical cognition: actions and circuits in behaving primates in Dopamine Handbook (Bjorklund A, Dunnett S, Iversen L, Iversen S, eds), Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK; 2009, pp. 230–49.

Shohamy D, Adcock RA. Dopamine and adaptive memory. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2010;14:464–72.

Mohebi A, Pettibone JR, Hamid AA, Wong J-MT, Vinson LT, Patriarchi T, et al. Dissociable dopamine dynamics for learning and motivation. Nature. 2019;570:65–70.

Bernow N, Yakushev I, Landvogt C, Buchholz H-G, Smolka MN, Bartenstein P, et al. Dopamine D2/D3 receptor availability and venturesomeness. Psychiatry Res. 2011;193:80–84.

Okita K, Ghahremani DG, Payer DE, Robertson CL, Dean AC, Mandelkern MA, et al. Emotion dysregulation and amygdala dopamine D2-type receptor availability in methamphetamine users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;161:163–70.

Kobiella A, Vollstädt-Klein S, Bühler M, Graf C, Buchholz H-G, Bernow N, et al. Human dopamine receptor D2/D3 availability predicts amygdala reactivity to unpleasant stimuli. Hum Brain Mapp. 2010;31:716–26.

Milella MS, Fotros A, Gravel P, Casey KF, Larcher K, Verhaeghe JAJ, et al. Cocaine cue-induced dopamine release in the human prefrontal cortex. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2016;41:322–30.

Meador-Woodruff JH, Damask SP, Watson SJ. Differential expression of autoreceptors in the ascending dopamine systems of the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8297–301.

Jetté M, Desrosiers HTR. Survey of 5 months old infants: preliminary report from the Québec Longitudinal Study of Childhood Development (QLSCD). Montréal, QC, Canada. Ministère de La Santé et Des Services Sociaux. Gouvernement Du Québec; 1998.

Jetté MDGL. Survey description and methodology of the Longitudinal Study of Child Development in Québec (ELDEQ 1998-2002). Québec, Canada: Institut de La Statistique Du Québec; 2000.

Boivin M, Brendgen M, Dionne G, Dubois L, Pérusse D, Robaey P, et al. The Quebec newborn twin study into adolescence: 15 years later. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2013;16:64–9.

Côté SM, Orri M, Brendgen M, Vitaro F, Boivin M, Japel C, et al. Psychometric properties of the Mental Health and Social Inadaptation Assessment for Adolescents (MIA) in a population-based sample. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26:e1566.

Tremblay RE, Vitaro F, Gagnon C, Piché C, Royer N. A prosocial scale for the preschool behaviour questionnaire: concurrent and predictive correlates. Int J Behav Dev. 1992;15:227–45.

Behar L, Stringfield S. A behavior rating scale for the preschool child. Dev Psychol. 1974;10:601–10.

Cox SML, Castellanos-Ryan N, Parent S, Tippler M, Benkelfat C, Pihl RO, et al. An externalizing risk trajectory for substance use disorders: a longitudinal cohort study (Submitted 2019).

First MB, Williams JBW, Karg RS, Spitzer RL. Structured clinical interview for DSM-5 research version. Arlington, VA, USA: American Psychiatric Association; 2015.

Robinson SM, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI. Reliability of the timeline followback for cocaine, cannabis, and cigarette use. Psychol Addict Behav. 2014;28:154–62.

Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful slcohol consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804.

Woicik PA, Stewart SH, Pihl RO, Conrod PJ. The substance use risk profile scale: a scale measuring traits linked to reinforcement-specific substance use profiles. Addict Behav. 2009;34:1042–55.

Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51:768–74.

Torrubia R, Ávila C, Moltó J, Caseras X. The sensitivity to punishment and sensitivity to reward questionnaire (SPSRQ) as a measure of Gray’s anxiety and impulsivity dimensions. Pers Individ Dif. 2001;31:837–62.

Krank M, Stewart SH, O’Connor R, Woicik PB, Wall AM, Conrod PJ. Structural, concurrent, and predictive validity of the substance use risk profile scale in early adolescence. Addict Behav. 2011;36:37–46.

Stanford MS, Mathias CW, Dougherty DM, Lake SL, Anderson NE, Patton JH. Fifty years of the Barratt impulsiveness scale: an update and review. Pers Individ Dif. 2009;47:385–95.

Vandeweghe L, Matton A, Beyers W, Vervaet M, Braet C, Goossens L. Psychometric properties of the BIS/BAS scales and the SPSRQ in Flemish adolescents. Psychol Belg. 2016;56:406–20.

Van Laere K, Varrone A, Booij J, Vander Borght T, Nobili F, Kapucu OL, et al. EANM procedure guidelines for brain neurotransmission SPECT/PET using dopamine D2 receptor ligands, version 2. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:434–42.

Cox SML, Tippler M, Jaworska N, Smart K, Durand F, Allard D, et al. mGlu5 receptor availability in emerging adults at risk for addictions: effects of vulnerability traits and cannabis use (Submitted 2019).

Costes N, Dagher A, Larcher K, Evans AC, Collins DL, Reilhac A. Motion correction of multi-frame PET data in neuroreceptor mapping: simulation based validation. Neuroimage. 2009;47:1496–505.

Ad-Dab’bagh Y, Lyttelton O, Muehlboeck JS, Lepage C, Einarson D, Mok K, et al. The CIVET image-processing environment: a fully automated comprehensive pipeline for anatomical neuroimaging research. In: Corbetta M, Editor. Proceeding 12th Annual Meeting Organ Human Brain Mapp, Florence, Italy, 2006. p. 2266.

Collins DL, Evans AC. ANIMAL: validation and applications of nonlinear registration-based segmentation. Int J Pattern Recognit Artif Intell. 1997;11:1271–94.

Talairach J, Tournoux P, Rayport M (translator). Co-planar stereotaxic atlas of the human brain: 3-dimensional proportional system: an approach to cerebral imaging. Stuttgart, NY, USA: Thieme Medical Publishers; 1988.

Murty VP, Shermohammed M, Smith DV, Carter RMK, Huettel SA, Adcock RA. Resting state networks distinguish human ventral tegmental area from substantia nigra. Neuroimage. 2014;100:580–9.

Christian BT, Narayanan TK, Shi B, Mukherjee J. Quantitation of striatal and extrastriatal D-2 dopamine receptors using PET imaging of [18F]fallypride in nonhuman primates. Synapse. 2000;38:71–9.

Lammertsma AA, Hume SP. Simplified reference tissue model for PET receptor studies. Neuroimage. 1996;4:153–8.

Gallezot JD, Kloczynski T, Weinzimmer D, Labaree D, Zheng MQ, Lim K, et al. Imaging nicotine- and amphetamine-induced dopamine release in rhesus monkeys with [11C]PHNO vs [11C]raclopride PET. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:866–74.

Urban NBL, Slifstein M, Thompson JL, Xu X, Girgis RR, Raheja S, et al. Dopamine release in chronic cannabis users: a [11C]raclopride positron emission tomography study. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71:677–83.

Crews F, He J, Hodge C. Adolescent cortical development: a critical period of vulnerability for addiction. Pharm Biochem Behav. 2007;86:189–99.

Vosberg DE, Leyton M, Flores C. The netrin-1/DCC guidance system: dopamine pathway maturation and psychiatric disorders emerging in adolescence. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;25:297–307.

Cropley VL, Innis RB, Nathan PJ, Brown AK, Sangare JL, Lerner A, et al. Small effect of dopamine release and no effect of dopamine depletion on [18F]fallypride binding in healthy humans. Synapse. 2008;62:399–408.

Vijayraghavan S, Major AJ, Everling S. Neuromodulation of prefrontal cortex in non-human primates by dopaminergic receptors during rule-guided flexible behavior and cognitive control. Front Neural Circuits. 2017;11:91.

Pardey MC, Kumar NN, Goodchild AK, Cornish JL. Catecholamine receptors differentially mediate impulsive choice in the medial prefrontal and orbitofrontal cortex. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27:203–12.

Fotros A, Casey KF, Larcher K, Verhaeghe JAJ, Cox SML, Gravel P, et al. Cocaine cue-induced dopamine release in amygdala and hippocampus: a high-resolution PET 18Fallypride study in cocaine dependent participants. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:1780–8.

Kim B, Yoon S, Nakajima R, Lee HJ, Lim HJ, Lee Y-K, et al. Dopamine D2 receptor-mediated circuit from the central amygdala to the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis regulates impulsive behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E10730–9.

Thiel KJ, Wenzel JM, Pentkowski NS, Hobbs RJ, Alleweireldt AT, Neisewander JL. Stimulation of dopamine D2/D3 but not D1 receptors in the central amygdala decreases cocaine-seeking behavior. Behav Brain Res. 2010;214:386–94.

Di Ciano P, Everitt BJ. Neuropsychopharmacology of drug seeking: insights from studies with second-order schedules of drug reinforcement. Eur J Pharm. 2005;526:186–98.

Uddin LQ, Nomi JS, Hébert-Seropian B, Ghaziri J, Boucher O. Structure and function of the human insula. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2017;34:300–6.

Naqvi NH, Rudrauf D, Damasio H, Bechara A. Damage to the insula disrupts addiction to cigarette smoking. Science. 2007;315:531–4.

Rominger A, Cumming P, Xiong G, Koller G, Böning G, Wulff M, et al. [18F]Fallypride PET measurement of striatal and extrastriatal dopamine D 2/3 receptor availability in recently abstinent alcoholics. Addict Biol. 2012;17:490–503.

Jung Y, Montel RA, Shen PH, Mash DC, Goldman D. Assessment of the association of D2 dopamine receptor gene and reported allele frequencies with alcohol use disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1914940.

Olivetti PR, Balsam PD, Simpson EH, Kellendonk C. Emerging roles of striatal dopamine D2 receptors in motivated behaviour: implications for psychiatric disorders. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019 [ePub ahead of print].

Bello EP, Jeong N, Goldman O, Simpson EH Abnormal dopamine reward prediction errors in a mouse model of chronic dopamine D2 receptor over-expression in the striatum. 11th Forum Neurosci Meet. Berlin, Germany. 2018.

Seaman KL, Smith CT, Juarez EJ, Dang LC, Castrellon JJ, Burgess LL, et al. Differential regional decline in dopamine receptor availability across adulthood: linear and nonlinear effects of age. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019;40:3125–38.

Wong DF, Young D, Wilson PD, Meltzer CC, Gjedde A. Quantification of neuroreceptors in the living human brain: III. D2-like dopamine receptors: theory, validation, and changes during normal aging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:316–30.

Porrino LJ, Daunais JB, Smith HR, Nader MA. The expanding effects of cocaine: studies in a nonhuman primate model of cocaine self-administration. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;27:813–20.

Beeler JA, Faust RP, Turkson S, Ye H, Zhuang X. Low dopamine D2 receptor increases vulnerability to obesity via reduced physical activity, not increased appetitive motivation. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79:887–97.

Berry AS, White RL, Furman DJ, Naskolnakorn JR, Shah VD, D’Esposito M, et al. Dopaminergic mechanisms underlying normal variation in trait anxiety. J Neurosci. 2019;39:2735–44.

Leyton M. Altered dopamine transmission as a familial risk trait for addictions. Curr Opin. Behav Sci 2017;13:130–8.

Alvanzo AAH, Wand GS, Kuwabara H, Wong DF, Xu X, McCaul ME. Family history of alcoholism is related to increased D2 /D3 receptor binding potential: a marker of resilience or risk? Addict Biol. 2017;22:218–28.

Volkow ND, Wang G-J, Begleiter H, Porjesz B, Fowler JS, Telang F, et al. High levels of dopamine D2 receptors in unaffected members of alcoholic families: possible protective factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:999–1008.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NJ aided with testing, carried out data analyses, and wrote the manuscript. SMLC aided with testing, data analyses and in revising the manuscript. MT aided with data collection. NCR, AD, JRS provided feedback on the manuscript, and advised on data analyses and interpretation; AD advised on PET analyses, in particular. NCR, SP FV, MB, SMC, RET, JRS are involved in overseeing the longitudinal cohorts from which participants in the current study were recruited. They were also implicated in characterizing externalizing traits throughout the lifespan in these cohorts. ML and JRS conceptualized the study, with input from CB and ROP. ML was responsible for overseeing data collection and interpretation, and manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jaworska, N., Cox, S.M.L., Tippler, M. et al. Extra-striatal D2/3 receptor availability in youth at risk for addiction. Neuropsychopharmacol. 45, 1498–1505 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-020-0662-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-020-0662-7

This article is cited by

-

A non-human primate model of cocaine addiction: interpreting associations with increased vs. decreased dopamine function

Neuropsychopharmacology (2023)

-

A three-factor model of common early onset psychiatric disorders: temperament, adversity, and dopamine

Neuropsychopharmacology (2022)

-

Mapping neurotransmitter systems to the structural and functional organization of the human neocortex

Nature Neuroscience (2022)

-

mGlu5 receptor availability in youth at risk for addictions: effects of vulnerability traits and cannabis use

Neuropsychopharmacology (2020)