Abstract

Extensive preclinical data implicate corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), acting through its CRH1 receptor, in stress- and dependence-induced alcohol seeking. We evaluated pexacerfont, an orally available, brain penetrant CRH1 antagonist for its ability to suppress stress-induced alcohol craving and brain responses in treatment seeking alcohol-dependent patients in early abstinence. Fifty-four anxious alcohol-dependent participants were admitted to an inpatient unit at the NIH Clinical Center, completed withdrawal treatment, and were enrolled in a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study with pexacerfont (300 mg/day for 7 days, followed by 100 mg/day for 23 days). After reaching steady state, participants were assessed for alcohol craving in response to stressful or alcohol-related cues, neuroendocrine responses to these stimuli, and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) responses to alcohol-related stimuli or stimuli with positive or negative emotional valence. A separate group of 10 patients received open-label pexacerfont following the same dosing regimen and had cerebrospinal fluid sampled to estimate central nervous system exposure. Pexacerfont treatment had no effect on alcohol craving, emotional responses, or anxiety. There was no effect of pexacerfont on neural responses to alcohol-related or affective stimuli. These results were obtained despite drug levels in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that predict close to 90% central CRH1 receptor occupancy. CRH1 antagonists have been grouped based on their receptor dissociation kinetics, with pexacerfont falling in a category characterized by fast dissociation. Our results may indicate that antagonists with slow offset are required for therapeutic efficacy. Alternatively, the extensive preclinical data on CRH1 antagonism as a mechanism to suppress alcohol seeking may not translate to humans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alcohol dependence (AD) is characterized by cycles of excessive alcohol consumption interspersed with intervals of abstinence, over time inducing persistent neuroadaptations that promote drug use (Heilig et al, 2010). Relapse is a key element of this disease process, and is frequently triggered by exposure to stress or drug-associated cues (Brownell et al, 1986). Blocking relapse induced by these types of stimuli is therefore a key objective for AD medications. Relapse has been modeled in experimental animals using reinstatement of drug seeking, following extinction (Bossert et al, 2013; Epstein et al, 2006). Studies using this approach have shown that the opioid antagonist naltrexone, an approved alcoholism medication, blocks cue-induced but not stress-induced relapse (Le et al, 1999; Liu and Weiss, 2002). In some individuals with stress-related alcohol use problems, such as those with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors or the alpha-1 andrenergic antagonis prazosin may offer clinical benefits (reviewed in Ipser and Stein, 2012). There are, however, no currently approved alcoholism medications that show consistently block stress-induced relapse. Developing such medications holds the promise of improving response rates in alcoholism treatment, through approaches that tailor treatment to individual differences (Heilig et al, 2011), via additive effects with existing therapeutics (Liu et al, 2002), or both.

Preclinical studies have identified several mechanisms with the potential to prevent stress-induced relapse in alcoholism (Heilig and Egli, 2006). Among these, antagonists of the corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) 1 receptor are widely thought to hold particular promise. Specifically, CRH1 receptors within the extended amygdala are upregulated, following a history of AD. Accordingly, systemic administration of brain penetrant CRH1 antagonists to rats with a history of dependence suppresses their escalated alcohol self-administration and blocks stress-induced reinstatement of alcohol seeking in a manner independent of effects on the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis (reviewed, eg, in Heilig and Koob, 2007; Zorrilla et al, 2013). Translation of these findings has, however, been slow to materialize. The first CRH1 antagonist evaluated in humans, R121919, showed promise in depression (Zobel et al, 2000), but its development was terminated due to safety issues widely shared by the first generation of CRH1 antagonists. CRH1 antagonists with improved safety followed, but yielded negative results both in depression (Binneman et al, 2008) and anxiety disorders (Coric et al, 2010). Blockade of CRH1 receptors has to date not been evaluated in patients with AD, the condition with, perhaps, the most consistent preclinical validation for the CRH system as a target.

To begin addressing this issue, we applied a biomarker-based experimental medicine strategy. Because CRH1 antagonists most effectively block stress-induced relapse and escalation of alcohol drinking in animals with elevated anxiety-like behavior (reviewed in Heilig and Koob, 2007), we attempted to enrich for the population most likely to respond, and focused on anxious alcohol-dependent patients. Exposure to stressful stimuli under human laboratory conditions can be used to induce craving for alcohol (Kwako et al, 2014; Sinha, 2009). Abstinent alcoholics show greater craving for alcohol and subjective distress compared with social drinkers when exposed to stressors such as personalized auditory scripts that evoke memories of stressful experiences (Sinha et al, 2009). Craving for alcohol induced by these experimental manipulations predicts a significant proportion of relapse risk (Sinha et al, 2011). The ability of candidate alcoholism medications to suppress cravings and emotional responses induced by experimental stressors can therefore be used as a surrogate biomarker predictive of clinical efficacy. Recent findings with gabapentin, a medication approved for treatment of seizures and neurogenic pain, support the notion that an ability to suppress alcohol cravings in response to the induction of negative emotions predicts clinical efficacy in alcoholism (Mason et al, 2014, 2009).

Here, we carried out a double-blind, placebo-controlled experimental medicine study to evaluate pexacerfont, a selective, orally available and brain-penetrant CRH1 antagonist with potent anti-anxiety activity in experimental animals in the absence of HPA axis effects (Gilligan et al, 2009; Zhou et al, 2012). We enrolled anxious, treatment-seeking alcohol-dependent patients, and examined whether pexacerfont would reduce their stress-induced craving for alcohol or neural responses to stressful stimuli presented during functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) sessions. To help interpret our results, we also examined plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of pexacerfont.

Materials and Methods

Subjects and General Procedure

Participants were recruited through advertisements, phone screened, and admitted to the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, MD where they underwent medically managed withdrawal, if needed. Once they had an undetectable breath alcohol concentration and did not require benzodiazepines for withdrawal, they were evaluated for eligibility. Detailed eligibility criteria are described at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01227980.

In brief, subjects were between 21–65 years old, diagnosed with AD according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (First et al, 1996), had scores >39 on the Spielberger State Trait Anxiety Inventory-Trait Version (STAI; Spielberger et al, 1970), and were in good physical health. They were excluded if they had complicated medical or psychiatric problems or were unable to participate in study procedures or provide informed consent. Informed consent was obtained as approved by the NIH Institutional Review Board.

Subjects in the main study were 55 individuals recruited during May 2011 to September 2013. Their baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. The sample size was based on the effect size for reduction in alcohol craving measured with the Alcohol Urge Questionnaire (AUQ; Bohn et al, 1995) under laboratory conditions, using the clinically approved alcoholism medication naltrexone, reported as Cohen’s d=1.3 (O'Malley et al, 2002). Our sample size was chosen to detect an effect size of Cohen’s d ⩾0.8 with a power ⩾0.80 at a two-tailed alpha of 0.05. Not all subjects successfully completed each procedure; n for each outcome is provided together with the respective results. Subjects were randomized to pexacerfont or matched placebo using a double-blind parallel group design with a 1:1 allocation. They received loading with 300 mg of pexacerfont given once daily for the first 7 days, followed by 100 mg once daily for 23 days, or placebo. Dosing was based on pharmacokinetic data indicating that by the end of a 1-week-loading phase, >90% of patients are above the projected human efficacious plasma pexacerfont concentration of 500 nM (Coric et al, 2010; Zhou et al, 2012).

All participants remained hospitalized throughout the study, and participated in standard-of-care behavioral alcoholism treatment. Upon inclusion, they were evaluated for alcoholism severity using the Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS; Skinner, 1984), for family history of alcoholism using the Family Tree Questionnaire (FTQ; Mann et al, 1985), for addiction severity phenotypes using the addiction severity index (ASI; McLellan et al, 1980), for alcohol consumption in the past 90 days prior to admission using the Timeline Follow-Back (TLFB; Sobell et al, 1986), for personality traits using the NEO Personality Inventory Revised (NEO; Costa, 2002), for PTSD symptom severity using the PTSD Symptom Severity Interview (PSSI; Foa et al, 1993), and for early life adversity using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein et al, 1994).

Time points given below for the respective procedure are all based on Day 1 being the day of receiving the first dose of study medication.

Neuroendocrine Testing

To assess the functional status of the HPA axis, participants underwent a dexamethasone-CRH (dex-CRH) test around day 15, carried out as described previously (Rydmark et al, 2006). Because of a temporary manufacturer shortage of CRH for human use, only a subset of 31 participants underwent this procedure.

Behavioral Challenge Sessions

Alcohol cravings and emotional responses were assessed in response to two sets of established challenge procedures. One of these combined the Trier Social Stress Test (Kirschbaum et al, 1993) with exposure to physical alcohol cues, ie, handling and smelling, but not consuming of each subject’s preselected alcoholic beverage (Stasiewicz et al, 1997). This combined challenge, hereafter called Trier/CR, was carried out as previously described (George et al, 2008; Kwako et al, 2014), around day 18 of the study. The other challenge procedure, described in (Kwako et al, 2014; Sinha et al, 2011), consisted of three sessions that used personalized auditory guided imagery scripts, each ∼5 min in duration, to present stress-, alcohol cue-associated, or neutral stimuli on days 24–26. The order of the script types was counterbalanced across subjects. Both challenge procedures (ie, Trier/CR and scripts) began at 3 pm to minimize differences in circulating cortisol.

During the challenge sessions, craving for alcohol was rated using the AUQ (Bohn et al, 1995). The Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS; Wolpe, 1969), a visual analog scale ranging 1–100 was used to assess emotional responses. ACTH and cortisol were used as endocrine stress markers. A timeline for experimental manipulations and data collection in the two challenge procedures is shown in Figure 1.

Timeline for procedures and data collection during challenge sessions used to provoke alcohol craving, subjective distress, and neuroendocrine responses used as biomarkers in this experimental medicine study. Upper panel: sessions utilizing guided imagery induced by auditory scripts; lower panel: sessions utilizing a combination of a social stress task and presentation of physical alcohol cues (‘Trier/CR’).

Functional Imaging

Around day 23 of the study, subjects underwent an fMRI scan. Imaging was on a 3T General Electric MRI scanner with a 12-channel head coil. Imaging paradigms included presentation of 130 negative, positive, and neutral pictures from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS; Lang et al, 1999). Scrambled images were used as the control condition and displayed during the inter-stimulus interval (ISI; 1.5–14, average 3.2 s). The scrambled images, derived from IAPS images, preserved brightness and color but did not contain recognizable features. Images were presented in random order in one run lasting 8 min. A second paradigm presented 90 pictures of alcoholic and neutral beverages (eg, milk, orange juice) in random order in a run lasting 6 min. Finally, 130 emotional (fearful, angry, happy, and neutral) faces (Matsumoto and Ekman, 1988), or a non-emotional control cross-hair (ISI), were presented for 8 min, in random order. Whole-brain images were collected for ∼22 min.

fMRI data were analyzed using Analysis of Functional Neural Images software (Cox, 1996). Statistical maps were generated for each individual by linear contrasts between regressors of interest (negative and positive IAPS images; alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages; happy, neutral, and fearful faces). Preprocessed time series data for each individual were then analyzed by multiple regression, which allowed covariation of variables related to head motion and other relevant factors such as, eg, subject age. We also calculated a statistical map of the activation within each group (pexacerfont and placebo) for each contrast of interest. Each condition was compared with the baseline scrambled image. We then performed voxel-wise t-tests of the β-coefficients calculated from the general linear model to test for differences between pexacerfont and placebo groups for each condition.

Pexacerfont Quantification in CSF and Plasma

To estimate central nervous system (CNS) exposure, we conducted a separate study (May to September 2013). A separate group of participants (n=10) was used in order to avoid influence of stressful effects of the spinal tap procedure on psychological and neuroendocrine outcomes. Individuals were recruited and screened as described above and received open-label pexacerfont using the dosing regimen of the main study. Their baseline characteristics did not differ from those of the main study sample (Supplementary Table S2). Within the last week of treatment, trough samples were obtained in the morning for the analysis of drug levels in plasma and CSF.

Pexacerfont quantification was performed by a novel ultrasensitive liquid chromotography-high resolution mass spectrometry method. Details of sample preparation procedures, analytical method, and performance parameters are provided in Supplementary Materials. Method validation was performed for both CSF and plasma matrices and included linearity; limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ); imprecision; accuracy; process efficiency; matrix effect; specificity; carryover; autosampler and short-term stability studies; and dilution integrity.

The assay was linear from 0.025 to 10 μg/l (CSF matrix) and 0.025 to 25 μg/l (plasma matrix) with an average (n=5) determination coefficient >0.994, and 1/ × 2 weighting. Residuals were always <20% for each calibrator. Linearity was thus considered acceptable. LOD and LOQ were 0.001 μg/l and 0.025 μg/l for both plasma and CSF. Total imprecision (n=15, %CV) was <6 and <8% for CSF and plasma, respectively. Intra-day (<5 and <6%) and inter-day (<3.6 and <5%) imprecision were acceptable. Accuracy also satisfied the criteria; QCs were quantified between 93 and 105% of theoretical concentrations.

Statistics

Behavioral data were analyzed using PROC MIXED for mixed-effect modeling in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), with treatment (pexacerfont/placebo) as the fixed, between-subjects factor. Repeated within-subject factors included time point (both Trier/CR and scripts outcome measures) and, for the scripts challenge, script condition (neutral, alcohol cue, or stress). Significance was set at p<0.05 for all tests, and all post hoc comparisons were conducted using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test. Potential covariates were evaluated on a model-by-model basis such that covariates that significantly predicted the outcome measure were retained in the model. Covariates that were evaluated included gender, race, age, ADS score, family history density from the FTQ, total score from the ASI, number of heavy drinking days from the TLFB, total score from the CTQ, neuroticism score from the NEO, overall PTSD symptom severity at baseline from the PSSI, and trait anxiety at baseline from the STAI. Model-specific covariates are noted in the relevant figure legends. The Kenward–Roger correction for denominator degrees of freedom (Kenward and Roger, 1997) was used in all models, as the use of this correction is highly recommended in repeated measures models with more complex covariance structures, especially when there is an unbalanced design (Littell, 2006).

Results

Guided Imagery Challenge Session

Craving responses

Exposure to guided imagery scripts reliably induced craving, as measured by the AUQ (Figure 2a). Specifically, whereas there was no main effect of script type, there was a significant main effect of time (F(7,281)=2.87, p=0.007) such that craving increased significantly during the first 5 min of script presentation, and a significant time by script-type interaction (F(14,589)=2.79, p=0.001). Post hoc analysis showed that craving at 5 min was higher following both the alcohol script and the stress script compared with the neutral script, supporting the validity of the design. There was, however, no main effect of pexacerfont treatment on craving in response to the stress (F(1,50)=1.53, p=0.22; Figure 2b) nor the alcohol script (F(1,51)=1.28, p=0.26; Figure 2c).

Alcohol-craving response to the guided imagery challenge session. (a) Effect of script type on alcohol craving. Covariates in the model included gender, years of education, and the total score from the ASI. The + indicates a significant difference between the 5 min and −15 min points (Tukey, p<0.05), whereas the * indicates a significant difference from the neutral script for both the alcohol and stress scripts (Tukey, p<0.05) at the 5-min time point. The sample size for this analysis was reduced due to missing data from the ASI for some of the subjects. (b) Effect of pexacerfont treatment on craving response to the stress script. Gender was a covariate in the model. (c) Effect of pexacerfont treatment on craving response to the alcohol cue script. Gender was a covariate in the model.

Subjective distress responses

Script exposure also induced subjective distress responses, as measured by the SUDS (Figure 3a). In this case, there was a significant main effect of script type (F(2,91)=4.18; p=0.018), a significant main effect of time (F(7,273)=5.23; p<0.0001), and a significant time by script-type interaction (F(14,557)=4.44; p<0.0001). Post hoc analysis showed that distress ratings at 5 min were higher, following the stress script than the neutral script, while this was not the case for the alcohol script. There was, however, no significant effect of treatment on distress ratings in response to the stress script (F(1,47)=1.61; p=0.21; Figure 3b) or the alcohol script (F(1,46)=0.27; p=0.61; Figure 3c). Similar results were seen for anxiety ratings measured by the Spielberger State Trait Anxiety Inventory, State Version (data not shown).

Subjective stress response to the guided imagery challenge session. (a) Effect of script type on subjective stress. Covariates in the model included gender, ADS score, and the total score from the ASI. The + indicates a significant difference between the 5 min and −15 min points (Tukey, p<0.05), whereas the * indicates a significant difference from the neutral script for both the alcohol and stress scripts (Tukey, p<0.05) at the 5-min time point. (b) Effect of pexacerfont treatment on subjective stress to the stress script. Covariates in the model included gender, ADS score, and the total score from the ASI. (c) Effect of pexacerfont treatment on subjective stress to the alcohol cue script. Covariates in the model included gender, ADS score, and the total score from the ASI.

Neuroendocrine responses

Script exposure did not significantly activate the HPA axis (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2). Specifically, there was no main effect of script type (F(2,102)=0.97; p=0.38) or time (F(9,361)=0.016; p=0.45) on cortisol levels. Although there was a significant script type by time interaction (F(18, 671)=1.72, p=0.03) in the mixed-effects model, none of the post hoc tests for cortisol levels were significant. Cortisol levels did not differ as a function of treatment during either the stress script (F(1,47)=1.03, p=0.31; Supplementary Figure S1B), or the alcohol script (F(1,46)=1.04; p=0.31; Supplementary Figure S1C). Similarly, there was no main effect of script type (F(2,88)=0.37; p=0.69) or time (F(9,325)=1.25; p=0.71), nor any script type by time interaction (F(18,673)=1.33; p=0.16) on the ACTH responses to the scripts. ACTH levels did not differ as a function of treatment during either the stress script F(1,42)=0.24; p=0.63; Supplementary Figure S2B), or the alcohol script (F(1,45)=1.03; p=0.32; Supplementary Figure S2C).

Trier/Cue-Reactivity Session

Craving responses

In response to the Trier/CR, there was a significant main effect of time (F(4,209)=9.38, p<0.0001; Figure 4a), such that craving for alcohol was significantly increased over baseline at 40 min. There was no effect of treatment on craving in response to the Trier/CR (F(1,67)=2.759 p=0.11), although participants on pexacerfont showed slightly higher numerical craving ratings compared with placebo.

(a) Effect of pexacerfont treatment on craving response to the Trier/CR. Gender was a covariate in the model. The + indicates a significant difference between the 40 min and −15 min time points (Tukey p<0.05). (b) Effect of pexacerfont treatment on subjective stress to the Trier/CR. Covariates in the model included gender, neuroticism, and the total score from the ASI. The + indicates a significant difference between the 20 min and −15 min time points (Tukey p<0.05). The sample sizes for the analyses of subjective stress were reduced due to missing data from the ASI for some of the subjects. (c) Effect of pexacerfont treatment on cortisol response to the Trier/CR. Covariates in the model included gender, race, and number of heavy drinking days from the TLFB. The + indicates a significant difference between the 20 min and −15 min time points (Tukey p<0.05). (d) Effect of pexacerfont treatment on ACTH response to the Trier/CR. Covariates in the model included gender, race, ADS score, and family history density from the FTQ. The + indicates a significant difference between the 20 min and −15 min time points (Tukey p<0.05).

Subjective distress responses

In response to the Trier/CR, there was a significant main effect of time (F(4,177)=9.13, p<0.0001; Figure 4b), such that distress ratings were significantly increased over baseline at 20 min. There was no main effect of treatment on subjective distress in response to the Trier/CR (F(1,54)=1.42 p=0.24).

Neuroendocrine responses

In response to the Trier/CR, there was a significant main effect of time (F(8,378)=20.99, p<0.0001; Figure 4c) on cortisol levels, such that cortisol was significantly increased over baseline by 20 min. A similar effect was observed for ACTH (main effect of time: F(8,373)=20.2, p<0.0001; Figure 4d), with ACTH levels significantly increased over baseline by 20 min. These HPA axis responses were similar to what we have previously observed in this model (George et al, 2008). There was no effect of pexacerfont treatment on either cortisol (F(1,61)=0.19; p=0.59) or ACTH levels (F(1,74)=0.01; p=0.96) during the Trier/CR.

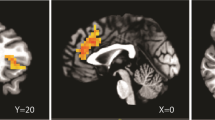

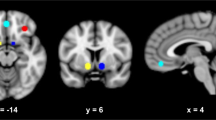

fMRI

In the placebo group, the expected response to fearful vs neutral faces was observed in the right amygdala (Figure 5a). There were no significant effects of pexacerfont treatment on this neural activation (Figure 5b). To minimize the likelihood of a Type 2 error, results were not whole-brain corrected. Similar to the face responses, no effect of pexacerfont was found for the other stimulus categories (data not shown).

Linear contrast of fMRI BOLD responses to fearful vs neutral faces. (a) In the placebo group, there was a predicted activation to fearful faces within the right amygdala (circled in red) (p<0.015, uncorrected). (b) A comparison between the pexacerfont and the placebo group did not reveal significant differences in activation of the amygdala or other brain regions.

dex-CRH Test

There were significant main effects of time on both cortisol (F(8,233)=7.68, p<0.0001) and ACTH levels (F(8,232)=7.16, p<0.0001) in response to the CRH challenge, with levels increasing over time for both measures (Supplementary Figure S3). There was no effect of pexacerfont treatment on either cortisol (F(1,37)=0.13; p=0.72) or ACTH (F(1,37)=0.09; p=0.76) during the dex/CRH challenge.

Pexacerfont Quantification in CSF and Plasma

Total plasma pexacerfont concentrations at trough were 765.7±95.7 nM (mean±SEM). Free pexacerfont in human plasma constitutes ∼3.9% of the total concentration (Zhou et al, 2012), yielding an estimate of free plasma pexacerfont in our study of ∼30.0±3.7 nM. Corresponding CSF concentrations were 36.4±5.1 nM, in close agreement with prior animal data, indicating a ratio between free pexacerfont in plasma and CSF close to unity (BMS, data on file). There was a high correlation between plasma and CSF levels (R2=0.89, p<0.001; Supplementary Figure S5). Based on the measured CSF concentrations and an estimated Kd of pexacerfont for the human CRH1 of 3.6 nM, central receptor occupancy (RO) was estimated to 89.3±3.2% (mean±SEM).

Discussion

We report that the orally available, brain-penetrant CRH1 antagonist pexacerfont failed to display activity across a range of behavioral, neuroimaging, and neuroendocrine outcomes when evaluated in alcohol-dependent inpatients during early abstinence. Pexacerfont left stress-induced alcohol craving as well as emotional distress responses unaffected in two different challenge models: guided imagery induced by auditory scripts, and the Trier/CR, a procedure that combines a social stressor with exposure to physical alcohol cues. fMRI BOLD responses to aversive as well as alcohol-associated stimuli were also unaffected by pexacerfont. A separate study showed that drug levels achieved in plasma were similar to those in a prior trial (Coric et al, 2010), and additionally provided the first human data on the resulting CNS exposure, assessed by drug levels in CSF.

Our study obtained craving- and distress-responses of a magnitude very similar to that reported in non-selected alcohol-dependent patients (see eg, Sinha et al, 2011), and shown to be sensitive to pharmacological effects (Fox et al, 2012). We did not directly evaluate the clinical efficacy of pexacerfont in alcoholism, and limited data are available to determine the predictive validity of the surrogate markers we obtained. The outcomes we evaluated are, however, in close homology with behaviors assessed in preclinical studies and thus appropriate for an initial translational study. Specifically, extensive preclinical findings predict that central CRH1 blockade will suppress stress-induced alcohol seeking, emotional distress, and underlying neural activity in alcohol-dependent individuals. In rats, non-selective and CRH1-selective antagonists block stress-induced relapse-like behavior (Gehlert et al, 2007; Le et al, 2000; Liu et al, 2002), and escalated alcohol self-administration that results from a history of dependence (Funk et al, 2007; Gehlert et al, 2007) or is induced by the pharmacological stressor yohimbine (Marinelli et al, 2007). Non-selective CRH or selective CRH1 antagonists also block the sensitized emotional stress responses observed in animals with a history of AD (Sommer et al, 2008; Valdez et al, 2003). Activity of CRH1 antagonists in these models is thought to reflect blockade of upregulated CRH transmission within the amygdala complex (Funk et al, 2006; Sommer et al, 2008) and effects in the dorsal raphe nucleus (Le et al, 2002, 2013), while being independent of the HPA axis (Le et al, 2000; Marinelli et al, 2007).

The affinity of pexacerfont for the CRH1 receptor is lower than that of some compounds that have been used in preclinical studies, such as, eg, MTIP used in our own prior work (for comparative data, see Zorrilla et al, 2013). However, in vivo potency of pexacerfont in animal models appears comparable or superior to that of commonly used reference compounds. For instance, pexacerfont was effective in two rat models of anxiety at 10 mg/kg (Gilligan et al, 2009), whereas a dose of 20 mg/kg of antalarmin was required for anxiolytic-like effects in an overlapping set of models (Zorrilla et al, 2002). Prior to our human study, we carried out experiments to confirm the comparative in vivo potency of pexacerfont in a rat model of an alcohol-related behavior, and found that its systemic administration was 3–10 times more potent to reverse ‘hangover anxiety’ than that of MTIP (pexacerfont: Supplementary Figure S6; MTIP: Gehlert et al, 2007).

The potential for attenuating physiological HPA axis activity represents a potential safety concern with CRH1 antagonists. The observation that pexacerfont left the HPA axis response to stressors unaffected was, however, expected because animal studies have shown that CRH1 antagonists suppress behavioral stress responses including alcohol seeking through central, extrahypothalamic systems, in the absence of HPA axis effects (see eg, Gehlert et al, 2007; Le et al, 2000). Estimating central RO achieved by CRH1 antagonists is therefore critical for properly interpreting clinical results obtained with these drugs in behavioral disorders, but remains challenging in the absence of a displaceable PET ligand. Modeling has predicted central RO in excess of 80% following pexacerfont loading with 300 mg daily for a week followed by the administration of 100 mg daily (Coric et al, 2010; Zhou et al, 2012), but considerable uncertainty is inherent in these predictions. It has therefore remained unclear whether negative clinical findings with CRH1 antagonists like pexacerfont in generalized anxiety disorder (GAD; Coric et al, 2010) reflect a true failure of the mechanism, or insufficient CNS exposure. We used the same dosing regimen as Coric et al, 2010, and obtained for the first time human data that provide an indication about CNS exposure. The estimated central RO in our study was close to 90%, in good correspondence with the modeling predictions. A previous study showed that 50% central CRH1 RO was sufficient for activity of a CRH1 antagonist in a rat anxiety model (Gilligan et al, 2000). Together, these data make it unlikely that insufficient CNS exposure accounts for the lack of pexacerfont activity in the published GAD trial, or in our present study.

Our study adds to a growing list of negative clinical trials with CRH1 antagonists in stress-related psychiatric disorders, including major depression (Binneman et al, 2008), GAD (Coric et al, 2010), and now AD. An important limitation of our study is the large male population examined. Nevertheless, these negative results, obtained despite considerable promise in preclinical models, are as surprising as they are disappointing. We can offer two different accounts for them, with very different implications. According to the first of these reviewed in Zorrilla et al, 2013, CRH1 antagonists with similar nominal receptor affinity may exhibit critically important differences in residence time on the receptor, reflected in their receptor dissociation rate under in vivo conditions. This account holds that slow off-rates are required for efficacy. Accordingly, R121919, for which positive results were reported in depression (Zobel et al, 2000), exhibits a slow off-rate, with a dissociation t1/2, an order of magnitude longer than those for CP316311, and pexacerfont. A second possibility that unfortunately cannot be excluded is that consistent observations of behavioral anti-stress effects of CRH1 antagonists in commonly used animal models simply do not translate to human disease conditions, for reasons that presently remain unknown.

FUNDING AND DISCLOSURE

Dr Sinha is on the scientific advisory board of Embera Neurotherapeutics and RiverMend Health. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K et al (1994). Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. A J Psychiatry 151: 1132–1136.

Binneman B, Feltner D, Kolluri S, Shi Y, Qiu R, Stiger T (2008). A 6-week randomized, placebo-controlled trial of CP-316,311 (a selective CRH1 antagonist) in the treatment of major depression. AJ Psychiatry 165: 617–620.

Bohn MJ, Krahn DD, Staehler BA (1995). Development and initial validation of a measure of drinking urges in abstinent alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 19: 600–606.

Bossert JM, Marchant NJ, Calu DJ, Shaham Y (2013). The reinstatement model of drug relapse: recent neurobiological findings, emerging research topics, and translational research. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 229: 453–476.

Brownell KD, Marlatt GA, Lichtenstein E, Wilson GT (1986). Understanding and preventing relapse. Am Psychol 41: 765–782.

Coric V, Feldman HH, Oren DA, Shekhar A, Pultz J, Dockens RC et al (2010). Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, active comparator and placebo-controlled trial of a corticotropin-releasing factor receptor-1 antagonist in generalized anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety 27: 417–425.

Costa PTM, R. R (2002) NEO Personality Inventory-Revised (NEO PI-R). APA: Washington, DC, USA.

Cox RW (1996). AFNI: Software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res 29: 162–173.

Epstein DH, Preston KL, Stewart J, Shaham Y (2006). Toward a model of drug relapse: an assessment of the validity of the reinstatement procedure. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 189: 1–16.

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW (1996) Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Clinician Version (SCID-CV). American Psychiatric Press, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA.

Foa EB, Riggs DS, Dancu CV, Rothbaum BO (1993). Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing posttraumatic-stress-disorder. J Trauma Stress 6: 459–473.

Fox HC, Anderson GM, Tuit K, Hansen J, Kimmerling A, Siedlarz KM et al (2012). Prazosin effects on stress- and cue-induced craving and stress response in alcohol-dependent individuals: preliminary findings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 36: 351–360.

Funk CK, O'Dell LE, Crawford EF, Koob GF (2006). Corticotropin-releasing factor within the central nucleus of the amygdala mediates enhanced ethanol self-administration in withdrawn, ethanol-dependent rats. J Neurosci 26: 11324–11332.

Funk CK, Zorrilla EP, Lee MJ, Rice KC, Koob GF (2007). Corticotropin-releasing factor 1 antagonists selectively reduce ethanol self-administration in ethanol-dependent rats. Biol Psychiatry 61: 78–86.

Gehlert DR, Cippitelli A, Thorsell A, Le AD, Hipskind PA, Hamdouchi C et al (2007). 3-(4-Chloro-2-morpholin-4-yl-thiazol-5-yl)-8-(1-ethylpropyl)-2,6-dimethyl-imidazo [1,2-b]pyridazine: a novel brain-penetrant, orally available corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 1 antagonist with efficacy in animal models of alcoholism. J Neurosci 27: 2718–2726.

George DT, Gilman J, Hersh J, Thorsell A, Herion D, Geyer C et al (2008). Neurokinin 1 receptor antagonism as a possible therapy for alcoholism. Science 319: 1536–1539.

Gilligan PJ, Baldauf C, Cocuzza A, Chidester D, Zaczek R, Fitzgerald LW et al (2000). The discovery of 4-(3-pentylamino)-2,7-dimethyl-8-(2-methyl-4-methoxyphenyl)-pyrazolo-[1,5-a]-pyrimidine: a corticotropin-releasing factor (hCRF1) antagonist. Bioorg Med Chem 8: 181–189.

Gilligan PJ, Clarke T, He L, Lelas S, Li YW, Heman K et al (2009). Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of 8-(pyrid-3-yl)pyrazolo[1,5-a]-1,3,5-triazines: potent, orally bioavailable corticotropin releasing factor receptor-1 (CRF1) antagonists. J Med Chem 52: 3084–3092.

Heilig M, Egli M (2006). Pharmacological treatment of alcohol dependence: target symptoms and target mechanisms. Pharmacol Ther 111: 855–876.

Heilig M, Egli M, Crabbe JC, Becker HC (2010). Acute withdrawal, protracted abstinence and negative affect in alcoholism: are they linked? Addict Biol 15: 169–184.

Heilig M, Goldman D, Berrettini W, O'Brien CP (2011). Pharmacogenetic approaches to the treatment of alcohol addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci 12: 670–684.

Heilig M, Koob GF (2007). A key role for corticotropin-releasing factor in alcohol dependence. Trends Neurosci 30: 399–406.

Ipser JC, Stein DJ (2012). Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 15: 825–840.

Kenward MG, Roger JH (1997). Small sample inference for fixed effects from restricted maximum likelihood. Biometrics 53: 983–997.

Kirschbaum C, Pirke KM, Hellhammer DH (1993). The 'Trier Social Stress Test'—a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology 28: 76–81.

Kwako LE, Schwandt ML, Sells JR, Ramchandani VA, Hommer DW, George DT et al (2014). Methods for inducing alcohol craving in individuals with co-morbid alcohol dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder: behavioral and physiological outcomes. Addict Biol ; e-pub ahead of print.

Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN (1999) International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Technical Manual and Affective Ratings. The Center for Research in Psychophysiology, University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA.

Le AD, Funk D, Coen K, Li Z, Shaham Y (2013). Role of corticotropin-releasing factor in the median raphe nucleus in yohimbine-induced reinstatement of alcohol seeking in rats. Addict Biol 18: 448–451.

Le AD, Harding S, Juzytsch W, Fletcher PJ, Shaham Y (2002). The role of corticotropin-releasing factor in the median raphe nucleus in relapse to alcohol. J Neurosci 22: 7844–7849.

Le AD, Harding S, Juzytsch W, Watchus J, Shalev U, Shaham Y (2000). The role of corticotrophin-releasing factor in stress-induced relapse to alcohol-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 150: 317–324.

Le AD, Poulos CX, Harding S, Watchus J, Juzytsch W, Shaham Y (1999). Effects of naltrexone and fluoxetine on alcohol self-administration and reinstatement of alcohol seeking induced by priming injections of alcohol and exposure to stress. Neuropsychopharmacology 21: 435–444.

Littell RC (2006). SAS. Encyclopedia of Environmetrics. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd..

Liu X, Weiss F (2002). Additive effect of stress and drug cues on reinstatement of ethanol seeking: exacerbation by history of dependence and role of concurrent activation of corticotropin-releasing factor and opioid mechanisms. J Neurosci 22: 7856–7861.

Mann RE, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Pavan D (1985). Reliability of a family tree questionnaire for assessing family history of alcohol problems. Drug Alcohol Depend 15: 61–67.

Marinelli PW, Funk D, Juzytsch W, Harding S, Rice KC, Shaham Y et al (2007). The CRF1 receptor antagonist antalarmin attenuates yohimbine-induced increases in operant alcohol self-administration and reinstatement of alcohol seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 195: 345–355.

Mason BJ, Light JM, Williams LD, Drobes DJ (2009). Proof-of-concept human laboratory study for protracted abstinence in alcohol dependence: effects of gabapentin. Addict Biol 14: 73–83.

Mason BJ, Quello S, Goodell V, Shadan F, Kyle M, Begovic A (2014). Gabapentin treatment for alcohol dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 174: 70–77.

Matsumoto D, Ekman P (1988). Japanese and Caucasian facial expressions of emotion and neutral faces (JACFEE and JACNeuF). Human Interaction Laboratory, University of California: San Francisco, CA, USA, 401.

McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, O'Brien CP (1980). An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. The Addiction Severity Index. J Nerv Ment Dis 168: 26–33.

O'Malley SS, Krishnan-Sarin S, Farren C, Sinha R, Kreek MJ (2002). Naltrexone decreases craving and alcohol self-administration in alcohol-dependent subjects and activates the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenocortical axis. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 160: 19–29.

Rydmark I, Wahlberg K, Ghatan PH, Modell S, Nygren A, Ingvar M et al (2006). Neuroendocrine, cognitive and structural imaging characteristics of women on longterm sickleave with job stress-induced depression. Biol Psychiatry 60: 867–873.

Sinha R (2009). Modeling stress and drug craving in the laboratory: implications for addiction treatment development. Addict Biol 14: 84–98.

Sinha R, Fox HC, Hong KA, Bergquist K, Bhagwagar Z, Siedlarz KM (2009). Enhanced negative emotion and alcohol craving, and altered physiological responses following stress and cue exposure in alcohol dependent individuals. Neuropsychopharmacology 34: 1198–1208.

Sinha R, Fox HC, Hong KI, Hansen J, Tuit K, Kreek MJ (2011). Effects of adrenal sensitivity, stress- and cue-induced craving, and anxiety on subsequent alcohol relapse and treatment outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 68: 942–952.

Skinner HA (1984). Assessing alcohol-use by patients in treatment. Res Adv Alcohol Drug 8: 183–207.

Sobell MB, Sobell LC, Klajner F, Pavan D, Basian E (1986). The reliability of a timeline method for assessing normal drinker college students' recent drinking history: utility for alcohol research. Addict Behav 11: 149–161.

Sommer WH, Rimondini R, Hansson AC, Hipskind PA, Gehlert DR, Barr CS et al (2008). Upregulation of voluntary alcohol intake, behavioral sensitivity to stress, and amygdala crhr1 expression following a history of dependence. Biol Psychiatry 63: 139–145.

Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE (1970) STAI manual for the Stait-Trait Anxiety Inventory (‘self-evaluation questionnaire’). Consulting Psychologists Press: Pal’o Alto, CA, USA, 24 p. pp.

Stasiewicz PR, Gulliver SB, Bradizza CM, Rohsenow DJ, Torrisi R, Monti PM (1997). Exposure to negative emotional cues and alcohol cue reactivity with alcoholics: a preliminary investigation. Behav Res Ther 35: 1143–1149.

Valdez GR, Zorrilla EP, Roberts AJ, Koob GF (2003). Antagonism of corticotropin-releasing factor attenuates the enhanced responsiveness to stress observed during protracted ethanol abstinence. Alcohol 29: 55–60.

Wolpe J (1969) The practice of behavior therapy 1st edn. Pergamon Press: New York, 314 p pp.

Zhou L, Dockens RC, Liu-Kreyche P, Grossman SJ, Iyer RA (2012). In vitro and in vivo metabolism and pharmacokinetics of BMS-562086, a potent and orally bioavailable corticotropin-releasing factor-1 receptor antagonist. Drug Metab Dispos 40: 1093–1103.

Zobel AW, Nickel T, Kunzel HE, Ackl N, Sonntag A, Ising M et al (2000). Effects of the high-affinity corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1 antagonist R121919 in major depression: the first 20 patients treated. J Psychiatr Res 34: 171–181.

Zorrilla EP, Heilig M, de Wit H, Shaham Y (2013). Behavioral, biological, and chemical perspectives on targeting CRF(1) receptor antagonists to treat alcoholism. Drug Alcohol Depend 128: 175–186.

Zorrilla EP, Valdez GR, Nozulak J, Koob GF, Markou A (2002). Effects of antalarmin, a CRF type 1 receptor antagonist, on anxiety-like behavior and motor activation in the rat. Brain Res 952: 188–199.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs Vlad Coric and Randy Dockens at BMS for support and valuable input, Dr George Grimes and his team at the NIH Pharmaceutical Development Services for enabling the study, Monte Phillips and NIH Clinical Center nursing staff for technical support, Drs Kenzie Preston and David Epstein for collaborating on studies using pexacerfont at the NIAAA and NIDA and for providing valuable comments, and Dr Yavin Shaham for reviewing and commenting on the manuscript. This study was supported by the NIAAA DICBR and carried out under a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement (CRADA) between the NIAAA and BristolMeyersSquibb. Clinical trials registration number: NCT00896038.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Neuropsychopharmacology website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kwako, L., Spagnolo, P., Schwandt, M. et al. The Corticotropin Releasing Hormone-1 (CRH1) Receptor Antagonist Pexacerfont in Alcohol Dependence: A Randomized Controlled Experimental Medicine Study. Neuropsychopharmacol 40, 1053–1063 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2014.306

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2014.306

This article is cited by

-

Wistar rats choose alcohol over social interaction in a discrete-choice model

Neuropsychopharmacology (2023)

-

Corticotropin-Releasing Factor receptor 1 (CRF1) antagonism in patients with alcohol use disorder and high anxiety levels: effect on neural response during Trier Social Stress Test video feedback

Neuropsychopharmacology (2023)

-

Neuroscience targets and human studies: future translational efforts in the stress system

Neuropsychopharmacology (2023)

-

Neuropeptidergic regulation of compulsive ethanol seeking in C. elegans

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Translational opportunities in animal and human models to study alcohol use disorder

Translational Psychiatry (2021)