Abstract

A quantum simulator is a well-controlled quantum system that can follow the evolution of a prescribed model whose behaviour may be difficult to determine. A good example is the simulation of a set of interacting spins, where phase transitions between various spin orders can underlie poorly understood concepts such as spin liquids. Here we simulate the emergence of magnetism by implementing a fully connected non-uniform ferromagnetic quantum Ising model using up to 9 trapped 171Yb+ ions. By increasing the Ising coupling strengths compared with the transverse field, the crossover from paramagnetism to ferromagnetic order sharpens as the system is scaled up, prefacing the expected quantum phase transition in the thermodynamic limit. We measure scalable order parameters appropriate for large systems, such as various moments of the magnetization. As the results are theoretically tractable, this work provides a critical benchmark for the simulation of intractable arbitrary fully connected Ising models in larger systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cold atomic systems provide an ideal standard for quantum simulation1,2, by virtue of their ability to support many classes of interactions as well as their excellent quantum coherence and readout properties. Spin chains with nearest-neighbour interactions have been simulated in neutral atoms stored in an optical lattice3,4, whereas long-range Ising models have been implemented with small numbers of trapped atomic ions5,6,7,8,9,10. The quantum coherence in such atomic systems should allow the observation of quantum phase transitions (QPTs)11 that are driven by non-thermal parameters, like the transverse magnetic field in the long-range quantum Ising model.

In the experiment reported here, we find the ground state of the transverse field Ising Hamiltonian for N interacting spin-1/2 systems:

where σiα is the Pauli matrix for the ith spin (α=x,y,z and i=1,2, ..., N), Ji,j>0 is the ferromagnetic (FM) Ising coupling matrix, with J=〈Ji,j〉 and B is an external effective magnetic field. Here we set Planck's constant h to unity, and use x,y,z for the Bloch sphere coordinates and X,Y,Z for the spatial coordinates throughout the paper. Our experiment is performed according to adiabatic quantum simulation protocol12, where the dimensionless coupling B/|J| is tuned slowly enough so that the system follows instantaneous eigenstates of the changing Hamiltonian8,9,10. As B/|J|→∞, the ground state has all spins polarized along the magnetic field, or is paramagnetic, along the Ising direction-x. In the other limit B/|J|=0, the spins order according to the Ising couplings and the ground state is a superposition of FM states |↑↑...↑〉 and |↓↓...↓〉 where |↑〉 and |↓〉 are eigenstates of σx.

We characterize the magnetic order in the system by measuring various correlation functions between all N spins, including the probability of FM occupation and the second and fourth moments of the total magnetization. We compare the results with theory, which itself may become intractable for non-uniform Ising couplings as the number of spins grows beyond 20–30 (ref. 13), and even NP complete for a fully connected frustrated Ising model14. This experiment is thus an important benchmark for large-scale quantum simulation.

Results

Engineering the quantum Ising Hamiltonian

We represent each spin-1/2 system by the hyperfine clock states 2S1/2|F=0,mF=0〉 and |F=1,mF=0〉 of 171Yb+ separated by vHF=12.642819 GHz (in a real magnetic field of ∼4 Gauss defining the quantization axis), which are denoted by the eigenstates ↓z and ↑z of σz, respectively. These states are detected by standard spin-dependent resonant fluorescence on the cycling 2S1/2 to 2P1/2 transition at 369.5 nm using a photomultiplier tube15. The ions are trapped along the Z axis of a three-layer linear Paul trap (Fig. 1a) with centre of mass (CM) vibrational frequencies of vX=4.748, vY=4.300, and vZ=1.002 MHz along the X,Y (transverse) and Z (axial) directions, respectively16. The modes of motion along X are cooled to near their vibrational ground states and within the Lamb–Dicke regime.

(a) Schematic of the three-layer linear radio frequency (Paul) trap, with the top and bottom layers carrying static potentials and the middle one carrying radio frequency. (b) Two Raman beams globally address the 171Yb+ ion chain, with their wave-vector difference ( ) along the transverse (X) direction of motion, generating the Ising couplings through a spin-dependent force. The same beams generate an effective transverse magnetic field by driving resonant hyperfine transitions. A CCD image showing a string of nine ions (not in present experimental condition) is superimposed. A photomultiplier tube (PMT) is used to detect spin-dependent fluorescence from the ion crystal. (c) Outline of quantum simulation protocol. The spins are initially prepared in the ground state of −B∑iσiy, then the Hamiltonian 1 is turned on with starting field B0≫|J| followed by an adiabatic exponential ramping to the final value B, keeping the Ising couplings fixed. Finally the x-component of the spins are detected.

) along the transverse (X) direction of motion, generating the Ising couplings through a spin-dependent force. The same beams generate an effective transverse magnetic field by driving resonant hyperfine transitions. A CCD image showing a string of nine ions (not in present experimental condition) is superimposed. A photomultiplier tube (PMT) is used to detect spin-dependent fluorescence from the ion crystal. (c) Outline of quantum simulation protocol. The spins are initially prepared in the ground state of −B∑iσiy, then the Hamiltonian 1 is turned on with starting field B0≫|J| followed by an adiabatic exponential ramping to the final value B, keeping the Ising couplings fixed. Finally the x-component of the spins are detected.

Off-resonant laser beams address the ions globally, driving stimulated Raman transitions between the spin states and also imparting spin-dependent forces exclusively in the X-direction, as depicted in Figure 1b9,10,17. The Raman beams contain a 'carrier' beat-note at frequency vHF, which provides an effective uniform transverse magnetic field B. Raman beatnotes at frequencies vHF±μ are near motional sidebands and generate a spin-dependent force. The radio frequency phase difference between the carrier beatnote and the average beatnote of the sidebands is set to π/2 so that the magnetic field is transverse to the Ising couplings (equation (1))9,10. We suppress direct sideband (phonon) excitation by ensuring that the beatnote detuning μ is sufficiently far from any normal mode frequency17. This requires that |μ−vm|≫ηi,mΩi, where ηi,m is the Lamb–Dicke parameter of the ith ion and mth normal mode at frequency vm (with v1=vX denoting the CM mode), and Ωi=g2i/Δ is the carrier Rabi frequency on the ith ion. Here gi is the single photon Rabi frequency of ith ion and Δ is the detuning of the Raman beams from the 2S1/2−2P1/2 transition.

This results in an Ising interaction between the spins with control parameter μ that dictates the form of the coupling matrix17.

In the experiment Δ∼2.7 THz, Ωi∼370 kHz and we expect Ji,j/N∼1 kHz for the beatnote detuning μ such that μ−v1≈4ηi,1Ωi, as shown in Figure 2a. This beatnote corresponds to 63 KHz blue of the CM mode frequency for 2 ions and 30 KHz for 9 ions, as the Lamb–Dicke parameter ηi,m∼1/√N. This maintains roughly the same level of virtual phonon excitation for any number of ions. The expected Ising coupling pattern for a uniformly illuminated ion chain is shown in Figure 2b for N=9 ions and the couplings are dominated by uniform contribution of the CM mode. The non-uniformity in the Ising couplings arises from other vibrational modes and variation in Ωi across the ion chain for gaussian Raman beams with a waist of ∼70 μm along the ion chain and ∼6 μm perpendicular to the ion chain used in the experiment. For N=9 ions the chain is ∼14 μm long, and the variation in Ωi is ∼2%.

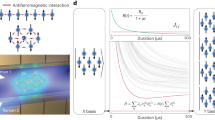

Transverse26 vibrational modes are used in the experiment to generate Ising couplings according to equation (2). (a) Raman sideband spectrum of vibrational normal modes along transverse X-direction for nine ions, labelled by their index m. The two highest frequency modes at v1 (CM mode) and  ('tilt' mode) occur at the same position independent of the number of ions. The dotted and the dashed lines show beatnote detunings of μ≈v1+30 KHz and μ≈v1+63 KHz used in the experiment for N=9 and N=2 ions respectively. Carrier transition, weak excitation of transverse -Y and axial -Z normal modes and higher order modes are faded (light grey) for clarity. (b) Theoretical Ising-coupling pattern (equation (2)) for N=9 ions and uniform Raman beams. The main contribution follows from the uniform CM mode, with inhomogeneities given by excitation through the other nearby modes (particularly the tilt mode). Here J1,1+r∼1/r0.35 (r≥1), as found out empirically. For larger detunings, the range of the interaction falls off even faster with distance, approaching the limit Ji,j∼1/|i−j|3 for μ≫v15.

('tilt' mode) occur at the same position independent of the number of ions. The dotted and the dashed lines show beatnote detunings of μ≈v1+30 KHz and μ≈v1+63 KHz used in the experiment for N=9 and N=2 ions respectively. Carrier transition, weak excitation of transverse -Y and axial -Z normal modes and higher order modes are faded (light grey) for clarity. (b) Theoretical Ising-coupling pattern (equation (2)) for N=9 ions and uniform Raman beams. The main contribution follows from the uniform CM mode, with inhomogeneities given by excitation through the other nearby modes (particularly the tilt mode). Here J1,1+r∼1/r0.35 (r≥1), as found out empirically. For larger detunings, the range of the interaction falls off even faster with distance, approaching the limit Ji,j∼1/|i−j|3 for μ≫v15.

Experimental protocol

In the experiment, we follow the highest excited state of the Hamiltonian-H (refs 8,17), which is formally equivalent to the ground state of Hamiltonian H (equation (1)). It proceeds as follows (Fig. 1c). We cool all the X-transverse modes of vibration to near their ground states, and deep within the Lamb–Dicke regime by standard Doppler and Raman sideband cooling procedures. We initialize the spins to be aligned to the y-direction of the Bloch sphere by optically pumping to |↓z↓z...↓z〉 and then coherently rotating the spins through π/2 about the Bloch x-axis with a carrier Raman transition. Next, we switch on the Hamiltonian H with an effective magnetic field B0∼5|J| so that the spins are prepared predominantly in the ground state. Then, we exponentially ramp down the effective magnetic field with a time constant of 80 μs to a final value B, keeping the Ising couplings fixed. We finally measure the spins along the Ising (x) direction by coherently rotating the spins through π/2 about the Bloch y-axis before fluorescence detection. We repeat the experiment ∼1,000×N times for a system of N spins and generate a histogram of fluorescence counts and fit to a weighted sum of basis functions to obtain the probability distribution P(s) of the number of spins in state (|↑〉), where s=0,1, ..., N, as described in the Methods section.

Extraction of order parameters from measured probabilities

We can generate several magnetic order parameters of interest from the distribution P(s), showing transitions between different spin orders. One order parameter is the average absolute magnetization (per site) along the Ising direction,  . Hamiltonian 1 has a global time-reversal symmetry of {σix→−σix, σiz→−σiz, σiy→σiy}, and this does not spontaneously break for a finite system, necessitating the use of average absolute value of the magnetization per site along the Ising direction as the relevant order parameter. For a large system, this parameter shows a second-order phase transition, or a discontinuity in its derivative with respect to B/|J|. On the other hand, the fourth-order moment of the magnetization or Binder cumulant

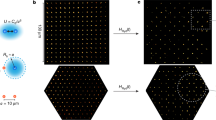

. Hamiltonian 1 has a global time-reversal symmetry of {σix→−σix, σiz→−σiz, σiy→σiy}, and this does not spontaneously break for a finite system, necessitating the use of average absolute value of the magnetization per site along the Ising direction as the relevant order parameter. For a large system, this parameter shows a second-order phase transition, or a discontinuity in its derivative with respect to B/|J|. On the other hand, the fourth-order moment of the magnetization or Binder cumulant  (refs 18,19) becomes a step function at the QPT and should therefore be more sensitive to the phase transition. We illustrate this point by plotting the exact ground-state order in the simple case of uniform Ising couplings for a moderately large system (N=100) in Figure 3a. Here we scale the two-order parameters properly to account for trivial finite size effects, as described in the Methods section. The scaled magnetization and Binder cumulant are denoted by

(refs 18,19) becomes a step function at the QPT and should therefore be more sensitive to the phase transition. We illustrate this point by plotting the exact ground-state order in the simple case of uniform Ising couplings for a moderately large system (N=100) in Figure 3a. Here we scale the two-order parameters properly to account for trivial finite size effects, as described in the Methods section. The scaled magnetization and Binder cumulant are denoted by  x and ḡ respectively. In Figure 3a, we also plot the exact ground-state order parameters for N=2 and N=9 spins. In Figure 3b-d, we present data for these two-order parameters, as B/|J| is varied in the adiabatic quantum simulation. Figure 3b shows the scaled magnetization,

x and ḡ respectively. In Figure 3a, we also plot the exact ground-state order parameters for N=2 and N=9 spins. In Figure 3b-d, we present data for these two-order parameters, as B/|J| is varied in the adiabatic quantum simulation. Figure 3b shows the scaled magnetization,  x for N=2 to N=9 spins that depict the sharpening of the crossover curves from paramagnetic to ferromagnetic spin order with increasing system size. The linear time scale indicates the exponential ramping profile of the (logarithmic) B/|J| scale. Figure 3c,d compares the two extreme system sizes in the experiment, N=2 and N=9, and clearly shows the increased steepness for larger system size. The scaled magnetization

x for N=2 to N=9 spins that depict the sharpening of the crossover curves from paramagnetic to ferromagnetic spin order with increasing system size. The linear time scale indicates the exponential ramping profile of the (logarithmic) B/|J| scale. Figure 3c,d compares the two extreme system sizes in the experiment, N=2 and N=9, and clearly shows the increased steepness for larger system size. The scaled magnetization  x is suppressed by ∼25% (Fig. 3b,c) and the scaled Binder cumulant ḡ is suppressed by ∼10% (Fig. 3d) from unity at B/|J|=0, predominantly due to decoherence from off-resonant spontaneous emission and additional dephasing due to intensity fluctuations in Raman beams, during the simulation.

x is suppressed by ∼25% (Fig. 3b,c) and the scaled Binder cumulant ḡ is suppressed by ∼10% (Fig. 3d) from unity at B/|J|=0, predominantly due to decoherence from off-resonant spontaneous emission and additional dephasing due to intensity fluctuations in Raman beams, during the simulation.

(a) Theoretical values of order parameters  x and ḡ are plotted vs B/|J| for N=2 and N=9 spins with non-uniform Ising couplings as used in the experiment in the case of a perfectly adiabatic time evolution. The order parameters are calculated by directly diagonalizing Hamiltonian 1. Order parameters are also calculated for a moderately large system (N=100) with uniform Ising couplings, to show the difference between the behaviours of

x and ḡ are plotted vs B/|J| for N=2 and N=9 spins with non-uniform Ising couplings as used in the experiment in the case of a perfectly adiabatic time evolution. The order parameters are calculated by directly diagonalizing Hamiltonian 1. Order parameters are also calculated for a moderately large system (N=100) with uniform Ising couplings, to show the difference between the behaviours of  x and ḡ. In case of uniform Ising couplings, the effective ground-state manifold reduces to N+1 dimensions in the total spin basis. The scaled Binder cumulant ḡ approaches a step function near the transition point B/|J|=1 unlike the scaled magnetization

x and ḡ. In case of uniform Ising couplings, the effective ground-state manifold reduces to N+1 dimensions in the total spin basis. The scaled Binder cumulant ḡ approaches a step function near the transition point B/|J|=1 unlike the scaled magnetization  x, making it experimentally suitable to probe the transition point for relatively small systems. (b) Scaled magnetization,

x, making it experimentally suitable to probe the transition point for relatively small systems. (b) Scaled magnetization,  x vs B/|J| (and simulation time) is plotted for N=2 to N=9 spins. As B/|J| is lowered, the spins undergo a crossover from a paramagnetic to ferromagnetic phase. The crossover curves sharpen as the system size is increased from N=2 to N=9, prefacing a QPT in the limit of infinite system size. The oscillations in the data arise because of imperfect initial state preparation and non-adiabaticity due to finite ramping time. The (unphysical) three-dimensional background is shown to guide eyes. (c) Magnetization data for N=2 spins (circles) is contrasted with N=9 spins (diamonds) with representative detection error bars. The data deviate from unity at B/|J|=0 by ∼20%, predominantly due to decoherence from spontaneous emission in Raman transitions and additional dephasing from Raman beam intensity fluctuation, as discussed in the text. The theoretical time evolution curves (solid line for N=2 and dashed line for N=9 spins) are calculated by averaging over 10,000 quantum trajectories (Methods). (d) Scaled Binder cumulant (ḡ) data and time evolution theory curves are plotted for N=2 and N=9 spins. At B/|J|=0 the data deviate by ∼10% from unity, due to decoherence as mentioned before.

x vs B/|J| (and simulation time) is plotted for N=2 to N=9 spins. As B/|J| is lowered, the spins undergo a crossover from a paramagnetic to ferromagnetic phase. The crossover curves sharpen as the system size is increased from N=2 to N=9, prefacing a QPT in the limit of infinite system size. The oscillations in the data arise because of imperfect initial state preparation and non-adiabaticity due to finite ramping time. The (unphysical) three-dimensional background is shown to guide eyes. (c) Magnetization data for N=2 spins (circles) is contrasted with N=9 spins (diamonds) with representative detection error bars. The data deviate from unity at B/|J|=0 by ∼20%, predominantly due to decoherence from spontaneous emission in Raman transitions and additional dephasing from Raman beam intensity fluctuation, as discussed in the text. The theoretical time evolution curves (solid line for N=2 and dashed line for N=9 spins) are calculated by averaging over 10,000 quantum trajectories (Methods). (d) Scaled Binder cumulant (ḡ) data and time evolution theory curves are plotted for N=2 and N=9 spins. At B/|J|=0 the data deviate by ∼10% from unity, due to decoherence as mentioned before.

We compare the data shown in Figure 3c,d with the theoretical evolution, taking into account experimental imperfections and errors discussed below, including spontaneous emission to the spin states and states outside the Hilbert space, and additional decoherence. The evolution is calculated by averaging 10,000 quantum trajectories. This takes only 1 minute on a single computing node for N=2 spins and approximately 7 h, on a single node, for N=9 spins. Extrapolating from this calculation suggests that averaging 10,000 trajectories for N=15 spins would require 24 hours on a 40-node cluster, indicating the inefficiency of classical computers to simulate even a small quantum system.

Discussion

A faithful quantum simulation requires an excellent understanding of errors and their scaling, especially when the underlying problem is otherwise intractable. We characterize errors in the current simulation by plotting the observed parameter P(FM)=P(0)+P(N) for N=2 to N=9 spins in Figure 4. Theoretically P(FM)=2/2N when there is no ferromagnetic order that is, P(FM)=0.5 for N=2 spins and exponentially goes down to 0.004 for N=9 spins, and unity, when there is perfect ferromagnetic order. Because P(FM) involves only two of the 2N basis states, it is more sensitive to errors compared with the order parameters  x and ḡ. For instance, at B/|J|=0 in Figure 3b-d and Figure 4a-d, we find that

x and ḡ. For instance, at B/|J|=0 in Figure 3b-d and Figure 4a-d, we find that  x and ḡ do not change appreciably with system size, but P(FM) degrades to ∼0.55 for N=9 spins from ∼0.9 for N=2. In Figure 4 we compare the data with theory results that include experimental sources of diabatic errors.

x and ḡ do not change appreciably with system size, but P(FM) degrades to ∼0.55 for N=9 spins from ∼0.9 for N=2. In Figure 4 we compare the data with theory results that include experimental sources of diabatic errors.

(a–d) Ferromagnetic order P(FM)=P(0)+P(N) is plotted vs B/|J| for N=2 to N=9 spins. The circles are experimental data, and the lines are theoretical results including decoherence and imperfect initialization. As this quantity includes only two of 2N basis states, random spin-flips and other errors degrade it much faster than the magnetization and Binder cumulant. The representative detection error bars are shown on a few points for each N. The P(FM) reduces from ∼0.9 to ∼0.55 as the system size is increased from two to nine. The principle contribution to this degradation is decoherence, predominantly due to spontaneous emission from intermediate 2P1/2 states in the Raman transition and additional dephasing, primarily due to intensity fluctuations in Raman beams. Shown in d is an estimated breakdown of the suppression of P(FM) from various effects for N=9 spins. Non-adiabaticity due to finite ramping speed, and spontaneous emission and additional dephasing due to fluctuating Raman beams suppress P(FM) by ∼8%, ∼18% and ∼24% respectively from unity (B/|J|→0).

There are several primary sources of experimental error. Diabaticity due to finite ramping speed and error in initialization is estimated to suppress P(FM) by ∼3% for N=2 to ∼8% for N=9. This also gives rise to oscillations seen in the data (Figs 3b–d, 4a–d). A major source of error is the spontaneous emission from Raman beams that amounts to a ∼10% spontaneous emission probability per spin in 1 ms. Spontaneous emission dephases and randomizes the spin state and loosely behaves like a 'spin temperature' in this system, though the spins do not fully equilibrate with the 'bath' and the total probability of spontaneous emission increases linearly during the quantum simulation. In addition, each spontaneous emission event populates other states outside of the Hilbert space of each spin with a probability of 1/3. Spontaneous emission errors grow with increasing system size, which also suppresses P(FM) order with increasing N, as seen in Figure 4a-d. We theoretically estimate the suppression of P(FM) due to diabaticity and spontaneous emission, together by averaging over quantum trajectories to be ∼7% for N=2 spins and ∼26% for N=9 spins. Intensity fluctuations on the Raman beams during the simulation modulate the AC Stark shift on the spins, and dephase the spin states, which causes additional diabaticity and degrades the final ferromagnetic order. When we introduce a theoretical dephasing rate of 0.3 per ms per ion (Methods) in the quantum trajectory computation the predicted suppression of P(FM) increases to ∼9% for N=2 and ∼50% for N=9.

Imperfect spin detection efficiency contributes ∼5–10% error in P(FM). Fluorescence histograms for P(0) and P(1) have a ∼1% overlap (in detection time of 0.8 ms) owing to off-resonant coupling of the spin states to the 2P1/2 level. This prevents us from increasing detection beam power or photon collection time to separate the histograms. Detection error in the data include uncertainty in fitting the observed fluorescence histograms to determine P(s), intensity fluctuations and finite width of the detection beam.

The role of phonons in the results of the quantum simulation is investigated both experimentally and numerically. The average number of centre of mass phonons excited during the simulation is numerically found to be always under 1.5 for N=9 spins, and even lower for N<9. We perform another set of experiments with μ−v1=63 KHz for all N, which amounts to reducing the phonon excitation as the number of spins N is increased, as the Lamb–Dicke parameter ηi,m∼1/√N. We do not note any appreciable difference (beyond the margin of experimental errors) in spin population with the results reported here. In the presence of an effective magnetic field, phonon modes are coherently populated and generally exhibit spin-motional entanglement. However, these phonons do not alter the spin ordering and hence preserve spin-spin correlation, even if the entanglement between spin states is partly destroyed when tracing over the phonon states. This will hence degrade entanglement characterization beyond a few spins using the standard GHZ type witness operators.

In this experiment, we have qualitatively observed sharpening of crossover curves that indicates the onset of a QPT as the system size increases. This scheme can be scaled up to a larger number of spins where it is possible to quantitatively estimate finite size effects, for example, scaling in critical exponents near the phase transition point20. The primary challenges in experimenting with larger system sizes include the spontaneous emission as described above, the requirement of larger optical power to maintain the same level of Ising couplings, and non-adiabatic effects due to shrinking gap between ground and first excited state21,22. One solution is to implement a high power laser with a detuning far from the 2P energy levels, which would minimize spontaneous emission while maintaining the same level of Ising couplings. This would also allow versatility in varying the Ising interaction (together with the effective external field) during the simulation, as the differential AC stark shift between spin states is negligible for a sufficiently large detuning. The coherence time increases in the absence of spontaneous emission, allowing for a longer simulation time necessary to preserve adiabaticity as the system grows in size. Recently Raman transitions have been driven using a mode-locked high power pulsed laser at a wavelength of 355 nm, which is optimum for 171Yb+ wherein the ratio of differential AC Stark shift to Rabi frequency is minimized and spontaneous emission probabilities per Rabi cycle are <10−5 per spin23.

With this system, it is possible to engineer different Ising coupling patterns by controlling the Raman beatnote detuning μ and observe interesting spin ordering such as with antiferromagnetic long-range couplings leading to frustration9,17, and phase transitions some of which can be very sharp, or of first order24. Long-range interactions in this spatially one-dimensional system allow for simulating multidimensional spin models by selectively exciting vibrational modes using multiple Raman beatnote detunings. With additional laser beams, this scheme can potentially simulate more complicated and higher spin-dimensional Hamiltonians like xy and xyz models, which map onto nontrivial quantum Hamiltonians such as the Bose-Hubbard Hamiltonian.

Methods

Detection of spin states

The spin states are detected by spin-dependent fluorescence signals collected through f/2.1 optics by a photomultiplier tube. Spin state |↑z〉 is resonantly excited by the 369.5 nm detection beam and fluoresces from 2P1/2 states, emitting Poisson-distributed photons with mean ∼12 in 0.8 ms. This state appears as 'bright' to PMT. The detection light is far off-resonant to spin state |↓z〉 and this state appears 'dark' to the PMT. However, due to weak off-resonant excitation bright state leaks onto dark state, altering the photon distribution25. Unwanted scattered light from optics and trap electrodes also alter the photon distribution. We construct the basis function for s bright ions by convolution techniques, and include a 5% fluctuation in the intensity of detection beam, which is representative of our typical experimental conditions. We then fit the experimental data to these basis functions, and obtain probabilities P(s) at each time step ti in the experiment. Mean photon counts for dark (mD) and bright (mB) states are used as fitting parameters so as to minimize the error residues.

The best fitting at time step ti is obtained for the parameters {mD,i,mB,i}. These parameters fluctuate at different time steps of the quantum simulation, primarily due to fluctuations in the intensity of detection beam and background scatter, and also due to uncertainties in a multivariate fitting. The fitting errors are propagated to the spin-state probabilities P(s) using Monte Carlo method of error analysis, as follows. We extract P(s) and compute the order parameters at time step ti with mean dark and bright state counts chosen randomly from a Gaussian distribution with mean { D,

D, B} and standard deviations {δmD,δmB} respectively. Here

B} and standard deviations {δmD,δmB} respectively. Here  D and ,

D and , B are averages of mD,i and mB,i respectively over different time steps ti. Similarly δmD and δmB are standard deviations of mD,i and mB,i respectively. By repeating this process ∼400 times we generate a histogram of each order parameter and fit the histograms to a Gaussian distribution. The standard deviation of the distribution is chosen to represent the random error due to fitting in that order parameter. The uncertainty in amount of fluctuation of the detection beam power during the experiment is conservatively included in the error analysis by repeating the fitting process for a range of fluctuations. The finite width of the detection beam is taken care of by modelling the Gaussian beam having a three-step intensity profile with appropriate intensity ratios.

B are averages of mD,i and mB,i respectively over different time steps ti. Similarly δmD and δmB are standard deviations of mD,i and mB,i respectively. By repeating this process ∼400 times we generate a histogram of each order parameter and fit the histograms to a Gaussian distribution. The standard deviation of the distribution is chosen to represent the random error due to fitting in that order parameter. The uncertainty in amount of fluctuation of the detection beam power during the experiment is conservatively included in the error analysis by repeating the fitting process for a range of fluctuations. The finite width of the detection beam is taken care of by modelling the Gaussian beam having a three-step intensity profile with appropriate intensity ratios.

Scaled order parameters

To characterize the spin orders we use different order parameters in the experiment, namely the average absolute magnetization per site (mx) and the Binder cumulant (g). When the spins are polarized along the y-direction of the Bloch sphere, the distribution of total spin along x-direction is Binomial and approaches a Gaussian (with zero mean) in the limit of N→∞. For system size of N, mx takes on theoretical value of  in the perfect paramagnetic phase (B/|J|→∞) and unity in the other limit of B/|J|=0. In Figure 3b,c, we rescale mx to

in the perfect paramagnetic phase (B/|J|→∞) and unity in the other limit of B/|J|=0. In Figure 3b,c, we rescale mx to  which should ideally be zero in perfect paramagnetic phase and unity in perfect ferromagnetic phase for any N. This accounts for the 'trivial' finite size effect due to the difference between Binomial and Gaussian distribution. Similarly the Binder Cumulant g is scaled to

which should ideally be zero in perfect paramagnetic phase and unity in perfect ferromagnetic phase for any N. This accounts for the 'trivial' finite size effect due to the difference between Binomial and Gaussian distribution. Similarly the Binder Cumulant g is scaled to  in Figure 3d, where

in Figure 3d, where  is the theoretical value of g for B/|J|→∞.

is the theoretical value of g for B/|J|→∞.

Quantum Monte-Carlo simulations

Quantum trajectories are generated by numerically integrating the Schrödinger equation, with Hamiltonian (1), while simultaneously executing quantum jumps to account for spontaneous emission and decoherence. Spontaneous emission from ion i either localizes the spin of the ion, projecting it into 2S1/2|F=0,mF=0〉 (spin state |↓z〉) or 2S1/2|F=1,mF=0〉 (spin state |↑z〉), or projects the ion into 2S1/2|F=1,mF=1〉, in which case ion i is factored out of the Schrödinger evolution, though it is counted as spin up at the time of measurement. Decoherence (dephasing) is modelled by the quantum jump operator σx; thus a jump for ion i, |ψψ〉→σix|ψψ〉, introduces a π phase shift between the spin states |↑〉 and |↓〉 (in x-basis). Jump rates are taken to be fixed and equal for all ions. Note that a decoherence jump rate of Γdecoh leads to decay of the spin coherence at rate 2Γdecoh. To determine the entangled state of the spin ensemble after a spontaneous emission, for example, from ion i, we assume that the ground-state configuration before emission,

is mapped, by the far-detuned Raman beams, into a very small excited-state contribution to the overall system entangled state,

with λ≪1 proportional to the amplitude of the Raman beams and inversely proportional to their detuning. The (unnormalized) state after the emission is

where |?〉i is |↑z〉i, |↓z〉i, or the factored state 2S1/2|F=1,mF=1〉.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Islam, R. et al. Onset of a quantum phase transition with a trapped ion quantum simulator. Nat. Commun. 2:377 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1374 (2011).

References

Feynman, R. Simulating physics with computers. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 21, 467–488 (1982).

Lloyd, S. Universal quantum simulators. Science 273, 1073 (1996).

Simon, J. et al. Quantum simulation of an antiferromagnetic spin chains in an optical lattice. Nature 472, 307–312 (2011).

Struck, J. et al. Quantum simulation of frustrated magnetism in triangular optical lattices arXiv:1103.5944.

Porras, D. & Cirac, J. I. Effective quantum spin systems with trapped ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92: 207901 (2004).

Deng, X.- L., Porras, D. & Cirac, J. I. Effective spin quantum phases in systems of trapped ions. Phys. Rev. A 72 (2005).

Taylor, J. M. & Calarco, T. Wigner crystals of ions as quantum hard drives. Phys. Rev. A 78: 062331 (2008).

Friedenauer, A., Schmitz, H., Glueckert, J. T., Porras, D. & Schaetz, T. Simulating a quantum magnet with trapped ions. Nature Phys. 4, 757–761 (2008).

Kim, K. et al. Quantum simulation of frustrated ising spins with trapped ions. Nature 465, 590–593 (2010).

Edwards, E. E. et al. Quantum simulation and phase diagram of the transverse-field ising model with three atomic spins. Phys. Rev. B 82: 060412 (2010).

Sachdev, S. Quantum magnetism and criticality. Nature Phys. 4, 173–185 (2008).

Farhi, E. et al. A quantum adiabatic evolution algorithm applied to random instances of an np-complete problem. Science 292, 472 (2001).

Lanczos, C. An iteration method for the solution of the eigenvalue problem of linear differential and integral operators. J. Res. Nat. Bur. Standards 45, 255–282 (1950).

Barahona, F. On the computational complexity of Ising spin glass models. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 15, 3241–3253 (1982).

Olmschenk, S. et al. Manipulation and detection of a trapped Yb+ hyperfine qubit. Phys. Rev. A 76: 052314 (2007).

Deslauriers, L. et al. Zero-point cooling and low heating of trapped 111Cd+ ions. Phys. Rev. A 70: 043408 (2004).

Kim, K. et al. Entanglement and tunable spin-spin couplings between trapped ions using multiple transverse modes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103: 120502 (2009).

Binder, K. Finite size scaling analysis of Ising model block distribution functions. Physik B 43, 119 (1981).

Binder, K. Critical properties from monte carlo coarse graining and renormalization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 47, 693–696 (1981).

Fisher, M. E. & Barber, M. N. Scaling theory for finite-size effects in the critical region. Phys. Rev. Lett. 28, 1516–1519 (1972).

Dusuel, S. & Vidal, J. Continuous unitary transformations and finite-size scaling exponents in the lipkin-meshkov-glick model. Phys. Rev. B 71: 224420 (2005).

Caneva, T., Fazio, R. & Santoro, G. E. Adiabatic quantum dynamics of the lipkin-meshkov-glick model. Phys. Rev. B 78: 104426 (2008).

Campbell, W. C. et al. Ultrafast gates for single atomic qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105: 090502 (2010).

Lin, G.- D., Monroe, C. & Duan, L.- M. Sharp phase transitions in a small frustrated network of trapped ion spins ArXiv 1011. 5885.

Acton, M. Detection and Control of Individual Trapped Ions and Neutral Atoms Ph.D. thesis (University of Michigan, 2008).

Zhu, S.- L., Monroe, C. & Duan, L.- M. Trapped ion quantum computation with transverse phonon modes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97: 050505 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We thank D. Huse for help with theoretical understanding of the quantum Ising model and finite-size scaling. This work is supported under Army Research Office under Award No. 911NF0710576 with funds from the DARPA Optical Lattice Emulator Program, IARPA under ARO contract, the NSF Physics at the Information Frontier Program, the European Program on Atomic Quantum Technologies, and the NSF Physics Frontier Center at JQI.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.I., E.E.E., K.K., S.K. and C.M. designed and performed the experiments, and analysed the data. C.N., H.C., G.-D.L., L.-M.D., C.-C.J.W and J.K.F provided theoretical support. C.N. and H.C. performed the quantum trajectory calculations. All the authors contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Islam, R., Edwards, E., Kim, K. et al. Onset of a quantum phase transition with a trapped ion quantum simulator. Nat Commun 2, 377 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1374

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1374

This article is cited by

-

Site-dependent control of polaritons in the Jaynes–Cummings–Hubbard model with trapped ions

Applied Physics B (2023)

-

Synchronous observation of information loss generating among ions in a long-range Paul trap chain

Applied Physics B (2023)

-

Flexible learning of quantum states with generative query neural networks

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Observation of Stark many-body localization without disorder

Nature (2021)

-

Variational fast forwarding for quantum simulation beyond the coherence time

npj Quantum Information (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.