Abstract

No published data concerning intraobserver and interobserver variability in the histopathological diagnosis of differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (DVIN) are available, although it is widely accepted to be a subtle and difficult histopathological diagnosis. In this study, the reproducibility of the histopathological diagnosis of DVIN is evaluated. Furthermore, we investigated the possible improvement of the reproducibility after providing guidelines with histological characteristics and tried to identify histological characteristics that are most important in the recognition of DVIN. A total number of 34 hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides were included in this study and were analyzed by six pathologists each with a different level of education. Slides were reviewed before and after studying a guideline with histological characteristics of DVIN. Kappa statistics were used to compare the interobserver variability. Pathologists with a substantial agreement were asked to rank items by usefulness in the recognition of DVIN. The interobserver agreement during the first session varied between 0.08 and 0.54, which slightly increased during the second session toward an agreement between −0.01 and 0.75. Pathologists specialized in gynecopathology reached a substantial agreement (kappa 0.75). The top five of criteria indicated to be the most useful in the diagnosis of DVIN included: atypical mitosis in the basal layer, basal cellular atypia, dyskeratosis, prominent nucleoli and elongation and anastomosis of rete ridges. In conclusion, the histopathological diagnosis of DVIN is difficult, which is expressed by low interobserver agreement. Only in experienced pathologists with training in gynecopathology, kappa values reached a substantial agreement after providing strict guidelines. Therefore, it should be considered that specimens with an unclear diagnosis and/or clinical suspicion for DVIN should be revised by a pathologist specialized in gynecopathology. When adhering to suggested criteria the diagnosis of DVIN can be made easier.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Vulvar carcinoma is rare with squamous cell carcinoma as the most common histopathological subtype. Nowadays, we can distinguish two types of squamous cell carcinoma with their own premalignant lesions.1, 2 The first type of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma consists of mainly non-keratinizing carcinomas and is caused by an infection with high-risk human papilloma virus (HPV). This type of carcinoma is associated with warty and/or basaloid vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN; together grouped as usual VIN (UVIN)). The second and most common type of carcinoma is differentiated keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma, often occurring in the background of lichen sclerosus. Differentiated VIN (DVIN), which is an entity that has no relation with HPV, is believed to be the precursor lesion associated with this type of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma.3, 4, 5

Until 2003, a three grade system for premalignant VIN (VIN grades 1–3, Table 1) was used. As clinicopathological data did not appear to support the concept of a continuous spectrum of VIN lesions leading to vulvar carcinoma that does exist for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical carcinoma,6, 7, 8 this grading system was abolished. The abandonment of VIN 1 and the consolidation of VIN 2 and 3 into one category simply termed (high-grade) VIN, best fitted the studies that have been performed on grading of VIN so far.6 Nowadays, the concept of usual VIN and differentiated VIN has been accepted more and more by clinical pathologists around the world.

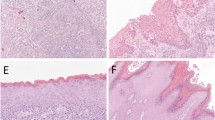

Histopathologically, usual VIN lesions are easy to recognize whereas the recognition of differentiated VIN is difficult as it is seldom diagnosed as a solitary lesion. DVIN is often found directly adjacent to squamous cell carcinoma and is characterized by a thickened epithelium that is typically associated with elongation and anastomosis of rete ridges (Figure 1a).4, 5, 9, 10, 11, 12 Dys- and parakeratosis are usually present (Figures 1e and f), associated with prominent intercellular bridges. Dyskeratosis is characterized by disturbed maturation and premature keratinization of squamous cells that are located deeper in the epithelium. In the parabasal layers of the epithelium, individual and clusters of cells show premature maturation, with large cells that show eosinophilia of the cytoplasm and even formation of keratin pearls (Figure 2). The nuclei have prominent nucleoli (Figure 1c), usually predominantly in the (para)basal keratinocytes (Figure 1e). Atypical mitotic figures (Figure 1d) may be seen mainly in the lower layers.4 The most superficial layers show normal maturation without atypical cells, although dyskeratosis may be present above the (para)basal layers with cells that have vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. As the cytological atypia in DVIN is confined to the basal epidermal cell layers, it is often confused with squamous hyperplasia or lichen sclerosus. The recognition of DVIN is hindered by a high degree of cellular differentiation combined with an absence of widespread architectural disarray, nuclear pleomorphism and diffuse nuclear atypia.9 Probably, this has led to a considerable underdiagnosis of DVIN. Although, it is of great importance to recognize this lesion properly because of its high malignant potential and rapid progression toward vulvar squamous cell carcinoma.4 Making the right pathological diagnosis is of utmost importance to assure proper treatment and follow-up.

Differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (DVIN). Overview of DVIN with (a) elongation and anastomosis of rete ridges, (b) disorderly basal cell layer and acanthosis, (c) prominent nucleoli and disorderly basal cell layer, (d) atypical mitoses, (e) and (f) dyskeratosis (indicated by arrows). Original magnifications: × 50 (a), × 100 (f), × 200 (b, c), × 400 (d, e).

(a) Overview of differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia with keratin pearl formation within the rete ridge (original magnification × 50). (b) Detail of keratin pearl formation, dyskeratosis and basal cellular atypia (original magnification × 100). (c) Detail of the basal layer with atypia and prominent nucleoli (original magnification × 200).

Until now, there are no published data on intra- and interobserver variability in the histopathological diagnosis of DVIN, although it is widely accepted to be a subtle and difficult histopathological diagnosis.5 In this study, the reproducibility of the histopathological diagnosis of DVIN is evaluated in a group of six Dutch pathologists with different level of experience. Furthermore, we investigated the possible improvement in diagnosing DVIN after providing guidelines with histological characteristics of DVIN. Finally, we tried to identify histological characteristics that are most important in the recognition of DVIN.

Patients and methods

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained slides of vulvar biopsies taken before the diagnosis of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma of 60 patients were collected, all patients subsequently developed vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. All patients were treated at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre (RUNMC) or the University Medical Centre Groningen between 1990 and 2008. The slides were reviewed by two experts in the field of gynecopathology from these two hospitals (JB and HH), independently and unaware of the course of the disease. Discrepancies in diagnoses were resolved in a consensus meeting with these two expert gynecologic pathologists (further on named ‘consensus pathologists’). Consensus diagnoses were based on published criteria, which are shown in Table 24, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 and considered to be the golden standard.

Of 60 slides, 46 were diagnosed as lichen sclerosus or DVIN during the consensus meeting. Thirty-five corresponding formalin fixed paraffin embedded specimens could be retrieved, re-cut at 4 μm, and H&E stained. To quicken the process of analysis, for each specimen a total number of three slides were re-cut. One consensus pathologist (JB) compared the slides from each specimen to confirm that these were comparable. As one specimen lost quality after re-cutting, it was excluded from further analysis. Finally, three identical sets of 34 slides were assessed for this study.

Six pathologists (consensus pathologists not included) were asked to classify all 34 slides in two separate sessions. The group of pathologists consisted of two gynecologic pathologists (pathologists that had special training in gynecopathology), two general pathologists and two pathologists in training. During the first session, the pathologists were asked to diagnose the lesions as lichen sclerosus, DVIN, high-grade dysplasia and/or other. When squamous cell carcinoma (n=4) was present next to lichen sclerosus or DVIN, the pathologists were asked to score both. No information about age, clinical aspect of the lesions or original diagnosis was provided. In between the first and second session, the pathologists were asked to study a guideline. This guideline was developed by the consensus pathologists (HH and JB) and consisted of the descriptive categories (lichen sclerosus, UVIN and DVIN) with extensive description of the pathological features (Table 2), illustrated by low- and high-power field photographs. After a washing out period of at least 3 months, the six pathologists were asked to study the guideline and diagnose the lesions as lichen sclerosus, DVIN and/or high-grade dysplasia and score the histological characteristics (Table 2). To evaluate the reproducibility of the histopathological diagnosis of DVIN, interobserver variability was calculated. Furthermore, the effect of education in each individual pathologist was assessed. To identify histological characteristics that were most important in the recognition of DVIN, one of the consensus pathologists on behalf of the consensus pathologists (JB) and pathologists with a high level of agreement were asked to put criteria in order of usefulness for the diagnosis of DVIN.

Statistical Methods

All slides diagnosed with DVIN by each pathologist were compared with the golden standard to give a level of agreement among pathologists. The kappa statistic, often used in studies in order to test the interobserver variability, was used. Values of 0.4–0.6, 0.6–0.8 and >0.8 were taken to reflect moderate, substantial or excellent correspondence, respectively.16 Analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Of the 34 slides assessed in this study, 20 (59%) were diagnosed as lichen sclerosus, 13 (38%) as DVIN and 1 (3%) as normal skin during the consensus meeting of the consensus pathologists. The median time to development of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma was 44 months (range 9–200); in patients with lichen sclerosus/normal skin this was 92 (range 9–200) months and with a prior biopsy of DVIN 24 (range 8–64) months. The agreement between the consensus pathologists (HH and JB) was 88%; 30 of 34 slides were scored concordant, with a kappa value of 0.73.

The distribution of collected data is shown in Table 3. The median time between the first and second session was 4 months (range 3–5 months). Pathologists D, E and F scored DVIN more often during the first session in comparison with the consensus, while pathologists A, B and C were less likely to score DVIN. The latter more often scored a lesion as high-grade dysplasia and/or other diagnosis, like aspecific dermatitis (n=13) or lichen planus (n=5). During the second session, the over- and underdiagnosis of DVIN remained present, although less clear. Pathologists were less likely to score high-grade dysplasia during the second session.

The interobserver agreement between pathologists during the first session varied between 0.08 and 0.54 (data not shown). The overall kappa that summarizes in a single coefficient the K values relative to the different pairs of pathologists, could not be calculated because of the heterogeneous K values. The interobserver agreement between pathologists after studying the guidelines during the second session slightly increased with values between −0.01 and 0.75.

Table 4 shows the kappa value of the diagnosis DVIN of individual pathologists vs consensus of the first and second session, categorized according to experience of the pathologist. The values range between 0.27 and 0.54 in the first session and between 0.15 and 0.75 in the second session. All pathologists increased in kappa value, except for pathologists B and C. Pathologists with training in the field of gynecopathology (gynecologic pathologists), could reach higher kappa values after studying the guidelines compared with general pathologists and pathologists in training.

Most important criteria in order of usefulness for the diagnosis of DVIN were scored by one of the consensus pathologists (JB) and pathologists with a high level of agreement (pathologist E and F) and are displayed in Table 5. The top five of these criteria included atypical mitoses in the basal layer, basal cellular atypia, dyskeratosis, prominent nucleoli, and elongation and anastomosis of rete ridges. A schematic overview of these criteria is displayed in Figure 3. All histological characteristics scored in slides with consensus of the diagnosis DVIN (n=22) of the pathologists with a substantial agreement (kappa value 0.7 or higher; pathologist E and F) were scored. The top five histological characteristics were identified in nearly all slides.

Five most important histological characteristics in the diagnosis of differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (DVIN) according to the pathologists with K>0.7 and the consensus pathologists. Schematic overview of: (a) normal epithelium and (b) DVIN with atypical mitosis in the basal layer, basal cell atypia, dyskeratosis, prominent nucleoli, and elongation and anastomosis of the rete ridges.

Discussion

With this study, we show that the agreement on the histopathological diagnosis of DVIN is low and diagnosing DVIN is difficult. After providing guidelines with histological characteristics to diagnose DVIN, agreement did improve but mainly in gynecologic pathologists, probably due to their long learning curves in the past. Therefore, it should be considered that specimens with an unclear diagnosis and/or clinical suspicion for DVIN should be revised by an experienced gynecologic pathologist.

Making the right diagnosis is of utmost importance to assure proper treatment and follow-up, as DVIN is known for its rapid progression toward squamous cell carcinoma.3, 4 Various studies11, 17, 18 highlighted the difficulty in making the clinical and histopathological diagnosis of DVIN. Unfortunately, this study shows that the pathological reproducibility is low in patients that subsequently developed a vulvar squamous cell carcinoma, which corresponds with the difficulties in diagnosing DVIN by the clinician.

Little is known about how pathologists differ in their interpretation of DVIN. It is widely accepted to be a subtle and difficult histopathological diagnosis as it can easily be mistaken for a benign dermatitis or epithelial hyperplasia5 and may be difficult to distinguish from the often present background of lichen sclerosus.17 To our knowledge, only three prior studies have addressed the interobserver variability of VIN19, 20, 21 of which all used the abandoned nomenclature of VIN 1–3 to classify the specimens. Trimble et al20 demonstrated moderate-to-good agreement among experienced gynecological pathologists in making the distinction between those lesions related to HPV and those that are not. Unfortunately, these lesions included squamous cell carcinoma and VIN 1–3; no agreement was calculated for the non-HPV VIN3. Preti et al19 showed an overall agreement of 73.9% for VIN 2/3 lesions, although no cases of differentiated VIN were included. Van Beurden21 showed a good agreement of 40 specimens with normal skin and VIN 1–3, of which possibly some of the VIN cases may be of the non-HPV type although this is not further clarified. Apparently, there is no literature that focuses on the histopathological diagnosis of DVIN.

The results of this study show that the diagnosis of different pathologists after providing guidelines with histological characteristics to diagnose DVIN, could only reach a substantial agreement of 0.75 (CI 0.52–0.98) in gynecologic pathologists. Obviously, in diagnosing DVIN, more practice leads to better skills as the highest agreement could be reached in pathologists with more experience. Likely, also continuous exposure of cases with differentiated VIN in daily practice is important to keep experience.

Apparently, studying the guidelines developed by the consensus pathologists (JB and HH) based on literature was not sufficient enough to increase the level of agreement among pathologists during the second session. A different approach in teaching general pathologists in the recognition of DVIN, for example, with an interactive session with an experienced gynecologic pathologist, may probably reach higher agreement. An interactive session, like a (virtual) workshop where clinically en pathologically doubtful DVIN lesions are being discussed may be helpful.

The low interobserver agreement indicates the need for some clarity in making the diagnosis DVIN properly. Therefore, we tried to identify the most important histopathological features by asking the consensus pathologists and pathologists with a substantial agreement, to rank the items that they thought were the most important in making the diagnosis of DVIN, which is shown in Table 5. We agree with Hart11 and Scurry13 that pathologists should not be focused on nuclear atypia alone, in the diagnosis of non-HPV premalignancy, but should also look for other supporting features. When some of the top five features listed in Table 5 are present, there has to be a concern and the diagnosis DVIN should be considered.

Besides the use of these histopathological criteria in making the right diagnosis, there may also be a role for immunohistochemistry.21, 22, 23 The use of MIB1 can be helpful to distinguish between normal vulvar epithelium and DVIN as the basal cell layer in DVIN shows a higher proliferation index (percentage of MIB1-positive cells), than normal vulvar epithelium, where the basal cell layer often is negative for MIB1.23 Furthermore, in DVIN a strong positive staining of the (supra)basal cell layers with p53 can be seen. Strong staining of all cell layers with p16 is suggestive for usual VIN and not for differentiated VIN.

An important and difficult problem, which we did not address in this study, is to decide whether one is looking at DVIN or invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Separated small nests of highly differentiated squamous cells may be seen in the dermis, raising the question of whether early invasion has taken place. In superficial biopsies, distinction of differentiated VIN from early invasive squamous cell carcinoma may be very difficult to make.11, 14 Therefore, it is important to keep to the classic criteria of invasiveness: small irregular nests of highly differentiated (atypic) squamous cells or individual strongly atypical cells with prominent nuceoli or/and a desmoplastic reaction around the invasive nests.

As most specimens with a suspicion of DVIN are seen by a general pathologist in daily practice, it is worthwhile considering revision of specimens with an unclear diagnosis and/or clinical suspicion for DVIN by an experienced gynecologic pathologist. Probably, interaction between the clinician and pathologist will also be helpful.

In conclusion, the histopathological diagnosis of DVIN is difficult as the interobserver agreement is low. Only among gynecologic pathologists, kappa values showed a substantional agreement after providing guidelines. To increase agreement among general pathologists, a more extensive instruction like (virtual) workshops with DVIN cases and doubtful lesions may be helpful. The histopathological features: atypical mitosis in the basal layer, basal cellular atypia, dyskeratosis, prominent nucleoli and elongation and anastomosis of the rete ridges that are ranked by pathologists with a substantional agreement, may be helpful in the diagnosis of DVIN.

References

van der Avoort IA, Shirango H, Hoevenaars BM et al. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma is a multifactorial disease following two separate and independent pathways. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2006;25:22–29.

Maclean AB . Vulval cancer: prevention and screening. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2006;20:379–395.

Eva LJ, Ganesan R, Chan KK et al. Differentiated-type vulval intraepithelial neoplasia has a high-risk association with vulval squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2009;19:741–744.

van de Nieuwenhof HP, Bulten J, Hollema H et al. Differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia is often found in lesions, previously diagnosed as lichen sclerosus, which have progressed to vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol 2011;24:297–305.

Kokka F, Singh N, Faruqi A et al. Is differentiated vulval intraepithelial neoplasia the precursor lesion of human papillomavirus-negative vulval squamous cell carcinoma? Int J Gynecol Cancer 2011;21:1297–1305.

Sideri M, Jones RW, Wilkinson EJ et al. Squamous vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: 2004 modified terminology, ISSVD Vulvar Oncology Subcommittee. J Reprod Med 2005;50:807–810.

Preti M, Van Seters M, Sideri M et al. Squamous vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2005;48:845–861.

Darragh TM, Colgan TJ, Cox JT et al. The lower anogenital squamous terminology standardization project for HPV-associated lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2012;136:1266–1297.

van de Nieuwenhof HP, van der Avoort IA, de Hullu JA . Review of squamous premalignant vulvar lesions. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2008;68:131–156.

Wilkinson EJ . Premalignant and malignant tumors of the vulva In: Kurman RJ, Ellenson LH, Ronnett BM, (eds) Blaustein’s Pathology of the Female Genital Tract 6th edn Springer: New York, 2011, pp 55–103.

Hart WR . Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: historical aspects and current status. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2001;20:16–30.

McCluggage WG . Recent developments in vulvovaginal pathology. Histopathology 2009;54:156–173.

Scurry J, Campion M, Scurry B et al. Pathologic audit of 164 consecutive cases of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2006;25:176–181.

Scurry J, Wilkinson EJ . Review of terminology of precursors of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2006;10:161–169.

Mulvany NJ, Allen DG . Differentiated intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2008;27:125–135.

Koch GG, Landis JR, Freeman JL et al. A general methodology for the analysis of experiments with repeated measurement of categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:133–158.

Yang B, Hart WR . Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia of the simplex (differentiated) type: a clinicopathologic study including analysis of HPV and p53 expression. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:429–441.

Fox H, Wells M . Recent advances in the pathology of the vulva. Histopathology 2003;42:209–216.

Preti M, Mezzetti M, Robertson C et al. Inter-observer variation in histopathological diagnosis and grading of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: results of an European collaborative study. Int J Obstetrics Gynaecol 2000;107:594–599.

Trimble CLD-W M, Wilkinson EJ, Zaino RJ et al. Reproducibility of the histopathological classification of vulvar squamous carcinoma and intraepithelial neoplasia. J Low Genit Tract Dis 1999;3:98–103.

van Beurden M, de Craen AJ, de Vet HC et al. The contribution of MIB 1 in the accurate grading of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. J Clin Pathol 1999;52:820–824.

Hoevenaars BM, van der Avoort IA, de Wilde PC et al. A panel of p16(INK4A), MIB1 and p53 proteins can distinguish between the 2 pathways leading to vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer 2008;123:2767–2773.

van der Avoort IA, van der Laak JA, Paffen A et al. MIB1 expression in basal cell layer: a diagnostic tool to identify premalignancies of the vulva. Mod Pathol 2007;20:770–778.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jan C Hendriks and Joanne IntHout for their advice on statistical analysis and Leon CLT van Kempen for his excellent assistance with the start of the study design and data acquisition.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van den Einden, L., de Hullu, J., Massuger, L. et al. Interobserver variability and the effect of education in the histopathological diagnosis of differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Mod Pathol 26, 874–880 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2012.235

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2012.235

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Molecular characterization of invasive and in situ squamous neoplasia of the vulva and implications for morphologic diagnosis and outcome

Modern Pathology (2021)

-

Histological interpretation of differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN) remains challenging—observations from a bi-national ring-study

Virchows Archiv (2021)

-

VISTA: VIsual Semantic Tissue Analysis for pancreatic disease quantification in murine cohorts

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Differential expression patterns of GATA3 in usual and differentiated types of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: potential diagnostic implications

Modern Pathology (2018)

-

Differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN): the most helpful histological features and the utility of cytokeratins 13 and 17

Virchows Archiv (2018)