Abstract

Recurrent nevus phenomenon and regression in melanoma may have overlapping histologic features. The clinical findings and histologic changes in 357 cases of recurrent nevus phenomenon were compared with 34 cases of melanoma with regression. Regression was defined as (1) Early: dense lymphoid infiltrates replacing nests of melanocytes, (2) Intermediate: absence/ loss of tumor with replacement by mix of lymphocytes and melanophages and early fibrosis, and (3) Late: tumor absence with extensive fibrosis and telangiectasia, melanophages and epidermal effacement. Four broad histologic patterns of recurrent nevus were identified and classified into type 1: junctional melanocytic hyperplasia with effacement of the retiform epidermis and associated dermal scar, type 2: compound melanocytic proliferation with effacement of the retiform epidermis and associated dermal scar, type 3: junctional melanocytic hyperplasia with retention of the retiform epidermis, and type 4: compound melanocytic hyperplasia with retention of the retiform epidermis and scar. Melanomas with early and intermediate regression were recognizable due to the presence of residual melanoma. Melanomas with late regression had overlapping features of type 1 and 2 recurrent nevi. Type 3 recurrent nevi resembled primary melanoma with scar/fibrosis. Histologically, the vast majority of recurrent nevi are readily identifiable; however, partial biopsies or cases without prior knowledge of the original biopsy may lead to misdiagnosis. This is especially true in recurrent nevus and regression in malignant melanoma, where these two lesions share overlapping histologic features. Correlation with the clinical findings and prior biopsy will avoid these pitfalls.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Recurrent nevus is the development of a melanocytic lesion at the site of removal of a previous benign nevus.1, 2 Recognition of this phenomenon is important as some cases may resemble melanoma (pseudomelanoma).3, 4 We have also observed that some cases of recurrent nevi had histologic overlap with regression in malignant melanoma. In addition, most large studies predate the introduction of the dysplastic nevus concept, and available data on recurrence following removal of dysplastic nevus removal is sparse. In this study, we analyze the clinical and histologic findings in a large series of cases of recurrent nevi, and we compare these findings to the histologic changes seen in malignant melanoma with regression.

Materials and methods

All cases of recurrent nevi during the period 2000–2007 were selected from the files of Knoxville Dermatopathology Laboratory. Only those cases, in which the clinical history, original melanocytic lesion, and recurrent lesion were available for review, were included in the study.

The original melanocytic lesion and recurrent nevus hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides were reviewed and the following criteria were used to assess recurrent nevi: presence/absence of effacement of the retiform epidermis, junctional and/or dermal melanocytic hyperplasia, growth pattern, relationship of the melanocytic proliferation to the dermal scar, cytologic atypia of melanocytes, and presence / absence of residual nevus.

For comparison, 34 cases of unequivocal melanoma with regression were obtained from the Knoxville Dermatopathology Laboratory melanoma database, and using criteria generated by Kang et al,5 regression was defined as given below.

Early: dense lymphoid infiltrates replacing nests of melanocytes.

Intermediate: absence / loss of tumor with replacement by mix of lymphocytes and melanophages and early fibrosis.

Late: tumor absence with extensive fibrosis and telangiectasia, macrophages and epidermal effacement.

Results

Original Nevus Histological Data

The primary melanocytic neoplasms covered a broad spectrum of lesions: the most common type was characterized as ordinary nevi (64%), this included junctional (12 cases, 5%), dermal (35 cases, 16%), and compound (178 cases, 79%). Dysplastic nevi accounted for 28% of all cases, congenital nevi 6%, and specialized nevi (which included blue nevi and spindle cell nevi) accounted for 1% of cases. Three cases of malignant melanoma where also identified (1%; Table 1).

Recurrent Nevus Clinical Data

A total of 325 patients fulfilled our criteria and were included in this study. There was a female predominance with females accounting for 72%, and males 28%. Patients ranged in age from 7 to 92 years; with the average age being 32 and the median age of 30 years. The vast majority of recurrences (74%) occurred in patients under the age of 40 years (Table 2. By far, the most common site of recurrence was the back, followed by the abdomen and extremities (Table 3). The time to recur ranged from 1 to 63 months, with the average time to recur 8 months and the median 5 months. Most of the nevi (64%) recurred within 6 months (Table 4). In addition, 23 patients had more than one recurrent nevus occurring at separate locations and 6 patients had multiple recurrences of the same lesion, resulting in a total of 357 biopsies. There were 80 cases (23%) in which the primary lesion appeared to be completely excised.

Recurrent Nevus Histological Data

Repeatable histologic patterns were identified, and these were primarily based on (A) epidermal changes, that is, retention or effacement of retiform epidermis; and (B) junctional versus junctional and dermal melanocytic hyperplasia. On the basis of these criteria, we were able to broadly classify our lesions into four categories and calculate their relative frequencies (Table 5):

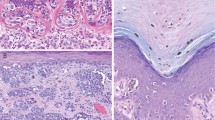

Type 1: Junctional melanocytic hyperplasia with effacement of the retiform epidermis (Figure 1a).

Histologic patterns of recurrent nevus phenomenon. In the histologic patterns types 1and 2, there is effacement of the retiform epidermis with junctional (a) and compound melanocytic hyperplasia (b), respectively. Dermal scar accompanies both biopsies. This is in contrast to types 3 and 4, where there is retiform epidermal hyperplasia, associated with junctional (c) and compound melanocytic hyperplasia (d), and dermal scar.

Type 2: Compound melanocytic hyperplasia with effacement of the retiform epidermis (Figure 1b).

Type 3: Junctional melanocytic hyperplasia with retention of the retiform epidermis (Figure 1c).

Type 4: Compound melanocytic hyperplasia with retention of the retiform epidermis (Figure 1d).

All these changes had to be associated with a dermal scar.

The melanocytes in the majority of our cases were arranged in nests in 265 cases (74%) with the remainder present as single cells. As noted in Table 5, almost half of our cases had a dermal component. Extension of melanocytes down adnexal structures was present in 6% of cases, and pagetoid upward migration was also observed in 6% of cases (Figure 2a). A confluent growth pattern was observed in 7 cases (2%), and a prominent dermal inflammatory reaction was noted in 21 cases (6%). Residual nevus was present in 117 cases (33%). Cytologically, the dominant melanocyte present had an epithelioid configuration with round nucleus and even chromatin pattern. Of note, concerning the cases with a dermal component, the dermal melanocytes retained the morphology of the junctional component, and transition to type B and C melanocytes was not evident (Figure 2b). Melanocytic atypia was defined as melanocytes with hyperchromasia and enlarged nuclei (greater than the nucleus of a keratinocyte in the stratum spinosum). Utilizing these criteria, 26% of biopsies showed melanocytic atypia (Table 6). In those cases with a retiform epidermis and accompanying atypical features, such as confluent growth pattern, pagetoid spread, and cytologic atypia, there was histologic overlap with primary melanoma (Figure 3a and b).

(a) In 20 cases, prominent pagetoid upward migration of melanocytes was present. This may be confused with melanoma in situ, if taken out of context. (b) Cytologically, the dominant melanocyte present had an epithelioid configuration with round nucleus and even chromatin pattern. The dermal melanocytes retained the morphology of the junctional component, and transition to types B and C melanocytes was not evident (b).

Malignant Melanoma with Regression Histologic Data

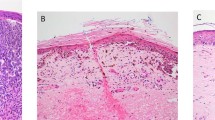

In all our cases, invasive malignant melanoma was present adjacent to areas of regression. In our 34 cases, there were 6 early, 14 intermediate, and 14 with late regressions. Malignant melanoma with early regression was easy to recognize, as dermal nests of melanoma cells were present intermingled with the lymphoid infiltrate and loss of melanocytes. However, in intermediate and late regressions, with increasing fibrosis, loss of melanoma cells, diminishing inflammatory response, and effacement of the retiform epidermis, unequivocal diagnosis of malignant melanoma in these areas was challenging, were it not for the adjacent changes of malignant melanoma. These cases of regression had features indistinguishable from cases of recurrent nevi with epidermal effacement, melanocytic atypia, and dermal fibrosis with inflammation (Figure 4a–f).

Histologic overlap of recurrent nevus and melanoma with regression. Recurrent nevus (a–c) and melanoma with regression (d–f). In partial biopsies, there may be considerable overlap between these two lesions. This was especially true for cases of MM with late regression with loss of tumor, effacement of the retiform epidermis, and fibrosis.

Discussion

In our series of cases, the majority of recurrent nevi occurred in females (72%) under the age of 40, with the back being the most common site and accounting for over half (57%) of the patients. The time to recurrence was less than 6 months for over 64% of cases, with only 4% recurring after 24 months following the primary biopsy/excision. These findings are similar to those reported by Park et al,6 with the exception of fewer head and neck cases seen in our series (28 versus 6%).

With regards to the patients' original nevi, almost two-thirds were ordinary nevi (64%). Of these, junctional accounted for 5% (12 cases), dermal for 16% (35 cases) and compound for 79% (178 cases). Dysplastic nevi accounted for 27% (96 cases) of the primary biopsies, and this phenomenon has not been described in previous large studies of recurrent nevi, because of the fact that these studies predate the dysplastic nevus concept. In a more recent smaller study of 15 cases of recurrent nevi, Hoang et al7 classified 3 of their 15 original biopsies as Clark (dysplastic) nevi. Although their series was small, it did account for 20% of their cases, similar to our findings. Given the relationship of dysplastic nevus to melanoma, a recurrent melanocytic lesion occurring at the site of a previously biopsied dysplastic nevus may be a cause for increased alarm and suspicion for malignancy. However, our series show that this phenomenon does occur with relative frequency, and proper correlation with the original biopsy will aid in correctly diagnosing this process.

We were able to identify repeatable histologic patterns occurring in our cases, on the basis of a combination of epidermal changes and location of recurrent nevus cells. The vast majority of recurrent nevi were readily identified histologically by the presence of the entire melanocytic proliferation (either junctional or compound) occurring within the confines of the scar. However, in partial biopsies, where the scar extended to the edges of the biopsy, differentiating recurrent nevi from an atypical melanocytic proliferation/melanoma proved problematic. This was particularly the case in which there was retention of the retiform epidermis (usually not observed overlying scars) and in which there was confluent proliferation of atypical melanocytes, histologically overlapping with primary melanoma. Earlier studies have not emphasized retiform epidermal changes and which we observed in 15% of our recurrent nevi cases.

The majority of our cases (85%) showed epidermal effacement with either a junctional or compound melanocytic proliferation, a pattern most commonly illustrated in prior publications,1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 and often showing pagetoid upward migration of melanocytes. In our series, it was this histologic pattern that showed pagetoid spread in 13% of cases (as opposed to 1% of cases of recurrent nevi with retiform epidermis). In addition, an inflammatory response was also noted in 13% of these cases. When we compared the above cases with intermediate and late stage regression in malignant melanoma, there was considerable overlapping histological changes that recurrent nevi could be interpreted as malignant melanoma with intermediate/late stage regression without the knowledge of patients' prior biopsy. This was especially true in cases where pagetoid and adnexal spread of melanocytes were present together with a dermal inflammatory response. Similarly, in our known cases of malignant melanoma, all had an invasive component to ensure that the cases we were dealing with were bone fide cases of regression. In analyzing the areas of regression, there were cases of late regression, which were indistinguishable from cases of recurrent nevi with effacement of the retiform epidermis and pagetoid and adnexal spread of cytologically atypical melanocytes. This may be a diagnostic pitfall with potentially serious consequences, and we have observed two cases in which the biopsy was thought to represent recurrent nevi and the re-excised specimen showed unequivocal invasive malignant melanoma (unpublished observations). In one case, we had no record of a prior nevus removal and the lesion extended to edge margins, leading us to recommend complete removal of the lesion. The re-excised specimen showed malignant melanoma, Clark level II, with regression. In the second case, we received in consultation, an excision from the lateral second toe showing malignant melanoma, acral lentiginous type, and Clark level II, with associated dermal scar. The prior biopsy, performed 1 year previously at another institution, was signed out as ‘consistent with recurrent nevus’. The lesion did extend to edge margins. No mention was made of the initial biopsy, which was interpreted at a third institution as an acral compound nevus, 3 years before that biopsy. In analyzing the entire case together, we interpreted the initial biopsy as malignant melanoma, Clark level II; the second biopsy as malignant melanoma, Clark level II with regression and scar; and the third biopsy as malignant melanoma, Clark level II, with regression. Both these cases highlight the overlapping histologic features of malignant melanoma with regression and recurrent nevi, and further emphasize the importance of the clinical findings and review of previous melanocytic biopsies at the site of recurrent nevi, especially in partial biopsies. This may become an increasingly important issue in view of the fragmentation of the health care system and the shipping of specimens to laboratories around the country.

Various theories have been proposed regarding the origin of recurrent nevi, and these include melanocytes repopulating from the adjacent epidermis,2, 8 repopulation from adnexal structures6, 9 and regrowth from residual dermal nevus.12 In 80 cases in our series, the primary lesion appeared to be completely excised, which would suggest that the regrowth from residual nevus was unlikely. Repopulation from adjacent epidermis would also seem less likely, and this is supported by the fact that in the completely re-excised recurrent nevi, the melanocytic proliferation was confined to the scar, and the adjacent unaltered epidermis did not show a similar proliferation. We believe that repopulation of melanocytes occur from remaining adnexal structures and migrate into the regenerating epithelium. This is supported by the elegant study of Nishimura et al,13 who in a mouse model showed that melanocyte stem cells can be found in the lower permanent portion of hair follicles. These stem cells were shown to be able to migrate to ‘niches’ lacking melanocytes and repopulate them. They further suggest that these stem cells could potentially be the source for both hair follicle and epidermal melanocytes.

Dermal nests of melanocytes occurred in a significant number of cases (151 biopsies, 42%), similar to that seen in the study by Park et al.6 In their study, they observed what they term ‘dropping off’ of epidermal nevus cells into the dermis in 36% of their cases. Interestingly, in their study, nine of their recurrent nevi cases were purely intradermal, a finding not seen in our study. We believe that the dermal nests do originate from the junctional component, as all our cases were associated with a junctional component and the cytology of the melanocytes in the dermis was identical to those in the junctional component. These findings suggest that these lesions were attempting to recapitulate the organization of ordinary nevi. On a practical note, awareness that dermal nests do occur with some frequency in recurrent nevi and that they are cytologically similar to the junctional melanocytes may help in correctly interpreting these lesions.

In summary, recurrent nevi tend to occur in young females with the back being the most common site and recurrence occurring relatively soon after the primary biopsy (8 months). Dysplastic nevi can recur and in our series did so frequently. Histologically, the vast majority of recurrent nevi are readily identifiable, however, partial biopsies or cases without prior knowledge of the original biopsy may lead to misdiagnosis. This is especially true in recurrent nevi and regression in malignant melanoma, where these two lesions share overlapping histologic features. Correlation with the clinical findings and prior biopsy will avoid these pitfalls.

References

Schoenfeld RJ, Pinkus H . The recurrence of nevi after incomplete removal. AMA Arch Derm 1958;78:30–35.

Cox AJ, Walton RG . The induction of junctional changes in pigmented nevi. Arch Pathol 1965;79:428–434.

Kornberg R, Ackerman AB . Pseudomelanoma: recurrent melanocytic nevus following partial surgical removal. Arch Dermatol 1975;111:1588–1590.

Hiss Y, Shafir R . ‘Pseudomelanoma’in a keloid. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1978;4:938–939.

Kang S, Barnhill RL, Mihm Jr MC, et al. Histologic regression in malignant melanoma: an interobserver concordance study. J Cutan Pathol 1993;20:126–129.

Park HK, Leonard DD, Arrington III JH, et al. Recurrent melanocytic nevi: clinical and histologic review of 175 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987;17:285–292.

Hoang MP, Prieto VG, Burchette JL, et al. Recurrent melanocytic nevus: a histologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Cutan Pathol 2001;28:400–406.

Cox AJ, Walton RG . Pigmented nevi. Induced changes in the junctional component. Calif Med 1966;104:32–34.

Imagawa I, Endo M, Morishima T . Mechanism of recurrence of pigmented nevi following dermabrasion. Acta Derm Venereol 1976;56:353–359.

Walton RG, Cox AJ . Electrodesiccation of pigmented nevi. Arch Dermatol 1963;87:342–349.

Walton RG, Sage RD, Farber EM . Electrodesiccation of pigmented nevi; biopsy studies: a preliminary report. AMA Arch Derm 1957;76:193–199.

Schreus HT . [Nevus and melanoma. I. Contribution to the histogenesis of nevus cell nevi.]. Hautarzt 1960;11:440–444.

Nishimura EK, Jordan SA, Oshima H, et al. Dominant role of the niche in melanocyte stem-cell fate determination. Nature 2002;416:854–860.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

King, R., Hayzen, B., Page, R. et al. Recurrent nevus phenomenon: a clinicopathologic study of 357 cases and histologic comparison with melanoma with regression. Mod Pathol 22, 611–617 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2009.22

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2009.22

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The journey from melanocytes to melanoma

Nature Reviews Cancer (2023)

-

Inactivation of the Hippo tumor suppressor pathway promotes melanoma

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Pushing and loss of elastic fibers are highly specific for melanoma and rare in melanocytic nevi

Archives of Dermatological Research (2019)

-

Melanocytic nevi and melanoma: unraveling a complex relationship

Oncogene (2017)