Abstract

Elevated blood pressure (BP) upon admission is common in patients with ischemic stroke (IS) and intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). Older patients have a higher prevalence of stroke, but data on admission mean arterial pressure (MAP) patterns in older patients with stroke are scarce. All 6060 patients with IS (72%), ICH (8%) and transient ischemic attack (TIA; 20%) with data on BP and hypertension status on admission in the National Acute Stroke Israeli Registry were included. Admission MAP in the emergency department was studied by age group (<60, 60–74 and ⩾75 years) and stroke type. Linear regression models for admission MAP were produced, including age group, gender, hypertension status and stroke severity as covariates. Interactions between hypertension and age were assessed. Lower MAP (s.d.) was associated with older ages in hypertensive patients (113 (18) mm Hg for age <60 years, 109 (17) for age 60–74 years and 108 (19) for age ⩾75 years, P<0.0001) but not in non-hypertensive IS patients. Among patients with ICH and TIA, a significant negative association of MAP with age was observed for hypertensive patients (P=0.015 and P=0.023, respectively), whereas a significant positive association with age was found in non-hypertensive patients (P=0.023 and P=0.038, respectively). In adjusted regression models, MAP was significantly associated with hypertension in IS, ICH and TIA patients. The interaction between hypertension and age was significantly associated with MAP in IS and ICH patients. In hypertensive patients, the average admission MAP was lower in persons at older ages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ischemic stroke (IS) and intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) are the most deleterious manifestations of cerebrovascular disease and their incidence increases with age.1 About 85% of all stroke cases are categorized as IS,1 and the number of elderly patients with IS is likely to increase significantly with the expected increase in life expectancy over the next decades. For each successive decade after the age of 55 years, IS rates double in both men and women.2

High systolic blood pressure (SBP) upon admission to the hospital is present in 75% of IS patients.3 This finding has been attributed to several factors, including preexisting hypertension,4 activation of the neuroendocrine systems (sympathetic nervous system,5 renin–angiotensin axis and glucocorticoid system6), increased cardiac output7 and emotional factors.8 It has been speculated that hypertension during the acute phase of IS might be advantageous by improving cerebral perfusion of the ischemic tissue.9 Elevated admission blood pressure (BP) is also frequently encountered in ICH, with BP values often exceeding those observed in IS.3 It is thought that the hypertensive response in ICH is triggered by increased intracranial pressure as well as the aforementioned mechanisms.10 Following this line of thought, it is not surprising that recent trials failed to show a beneficial effect of high BP treatment on short-term prognosis in IS11 and ICH.12

Older hypertensive patients have a higher prevalence of cerebrovascular atherosclerosis, including increased arterial stiffness13 and impaired cerebral autoregulation,14 but data on admission BP patterns in different age groups in acute stroke are scarce. Mean arterial pressure (MAP) is a major determinant of cerebral blood flow (CBF),15 which is critical to compromised brain tissue, and can be easily calculated from BP measurements.

We aimed to study admission emergency department MAP patterns among patients with acute stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA) across age groups.

Methods

Study design and setting

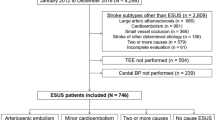

The National Acute Stroke Israeli Survey (NASIS) registry is an ongoing hospital-based project including all patients hospitalized owing to acute stroke or TIA in all hospitals treating stroke patients in Israel. Data are collected during 2-month periods triennially.16, 17 During the first three periods of NASIS (February–March 2004, March–April 2007 and April–May 2010), data on 6182 stroke and TIA patients were collected. The present study included 6060 patients (72.1% IS, 7.8% ICH and 20.1% TIA) with complete data on age, hypertension status and admission BP. The NASIS registry was approved by the ethical committees of the participating medical centers.

Data collection and definition of study variables

IS was differentiated from ICH per findings on brain imaging (computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging). ICH required evidence of intracerebral bleed per imaging; subarachnoid hemorrhage was excluded. A structured form was used for collection of data on patients’ characteristics, clinical diagnoses, stroke management, in-hospital complications and outcome at discharge. A coordinating physician at each medical center was assigned who was responsible for data collection per all information in the medical records. In cases of doubt regarding the diagnosis of a cerebrovascular event, the decision was made by a central adjudication committee. First SBP and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) on admission at the emergency department were recorded. MAP was calculated as DBP plus one-third times the pulse pressure on admission. Hypertension was defined by medical records, self-report or use of BP-lowering agents ⩾1 week before stroke onset. History of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) was determined by self-report and medical records. Severity of stroke was categorized into three NIH Stroke Scale (NIHSS)18 levels (NIHSS 0–5, 6–10, ⩾11).

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean and s.d. for continuous variables and frequency (%) for categorical variables. Three age groups were defined: <60, 60–74, and ⩾75 years. Patients’ characteristics, prevalence of risk factors and co-morbidities, stroke severity and etiology were studied by age group, and differences in rates were assessed with Mantel–Haenszel Chi-Square tests. Differences in MAP by age group were evaluated using General Linear Models overall and separately for hypertensive and non-hypertensive patients. Associations between age and MAP were studied using linear regression models, and interactions between age and prevalent hypertension were assessed. Three models were studied: model 1 including age group only; model 2 including in-addition hypertension and interaction between age and hypertension, and model 3 including in-addition sex, history of AMI, stroke severity, atrial fibrillation, dyslipidemia, prior dementia and cancer. Analyses were performed with SAS 9.3 (SAS, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patients’ characteristics

Characteristics of patients by age group are shown in Table 1. Of the 6060 patients, 3271 (54.0%) were men. Mean (s.d.) age of participants was 69.8 (13.5) years, range 18–105 years. Mean (s.d.) BP levels (mm Hg) were: SBP 157.1 (28.7); DBP 84.1 (15.9) and MAP 108.4 (18.1). Hypertension was reported in 4917 patients (81.1%). Rates of hypertension ranged from 62.2% in the <60-year-old group to 84.9% in 60–74 years and 88.6% in patients aged ⩾75 years (P<0.0001). The proportion of men significantly differed by age in hypertensive (P<0.0001) but not in non-hypertensive patients. Substantial differences in rates of almost all risk factors and co-morbidities were found between age groups. Rates of TIA were lower at older ages, and the proportion of minor strokes (NIHSS⩽5) was substantially lower at older ages in patients with and without hypertension.

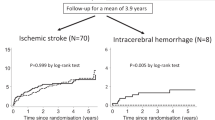

Age, hypertension and MAP at admission

In non-hypertensive stroke patients, mean (s.d.) SBP was significantly higher at older ages (139.07 (22.31) mm Hg for age <60 years vs. 153.15 (25.64) for age ⩾75 years, P<0.0001) while DBP was not significantly different. Among hypertensive stroke patients, no clear trend was observed in mean SBP, but DBP (s.d.) was significantly lower at older ages (89.28 (16.24) mm Hg for age <60 years vs. 81.84 (16.33) for age ⩾75 years, P<0.0001). MAP at admission was higher in patients with ICH (mean (s.d.)=117.1 (21.8) mm Hg) than in those with IS (108.4 (17.8)) and TIA (105.2 (16.2), P<0.0001) and was generally lower at older ages (Figure 1). However, the change in admission MAP differed by type of event and hypertension status (Figure 1, Table 2). In hypertensive patients, MAP was significantly higher at older ages in those with IS, ICH or TIA (Table 2; P<0.0001). In non-hypertensive patients, MAP did not differ across age categories in those with IS and was higher at older ages in those with ICH and TIA (Figure 1, Table 2; P<0.05).

Mean arterial pressure (MAP) in patients with acute cerebrovascular events by event type, age group and hypertension status. (a) Patients with ischemic stroke. (b) Patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Note: Data not presented for ICH patients without hypertension aged 65–69 years (n=2). (c) Patients with transient ischemic attack. A full color version of this figure is available at the Hypertension Research journal online.

Unadjusted regression models showed a negative association between age and MAP in IS patients aged ⩾75 years compared with <60 years. However, associations between MAP and age were not significant for any event type (IS, ICH or TIA) following adjustment for risk factors. Hypertension was positively associated with MAP, but older age significantly modified the effect of hypertension on MAP in IS and ICH patients such that older hypertensive patients with IS or ICH had lower MAP (P<0.0001 and P=0.045, respectively; Table 3).

Associations between other risk factors and MAP at admission

Negative association was observed between atrial fibrillation and MAP in patients with IS, ICH and TIA (P=0.001, P=0.03 and P=0.022, respectively; Table 3). Negative associations were also observed between history of AMI and MAP in patients with IS (P<0.0001), between dyslipidemia and MAP in patients with IS (P=0.0003) and between cancer and MAP in patients with IS (P=0.005; Table 3). Stroke severity was positively associated with MAP in patients with IS and NIHSS⩾11 (P=0.04). Sex, prior dementia and other stroke severity score categories were not associated with MAP at admission.

Discussion

In the present study, we used data from a national stroke registry (NASIS) to examine admission MAP in patients with IS, ICH and TIA. Our results show a previously unrecognized negative association of MAP with age in hypertensive patients with stoke or TIA. In non-hypertensive patients, admission MAP was not associated or positively associated with age in all types of events.

A decrease in CBF, as in IS and possibly in ICH, triggers autoregulatory mechanisms to attenuate the changes and preserve CBF. When these mechanisms reach their full compensatory capacity, CBF remains in direct correlation with MAP. A decline in MAP at this point would cause a further decrease in CBF. Older hypertensive stroke patients are therefore presumed to show higher than average admission MAP. However, our observation does not support this conception.

There are several possible explanations for our findings. First, as increased admission MAP may be the result of increased cardiac output,7 failure to increase MAP following a stroke event in older hypertensive patients may result from a diminished cardiac reserve, which is prevalent in this population.19 Hypertension is a major risk factor for heart diseases and the negative association of atrial fibrillation and prior AMI with admission MAP strongly supports this theory. Further support to this explanation can be derived from the observation of Balci et al.20 who demonstrated lower admission MAP in warfarin-associated ICH compared with aspirin and no-drug-associated ICH. As warfarin is usually prescribed for atrial fibrillation, this observation can be seen as consistent with ours. Both atrial fibrillation and a history of AMI are more prevalent in hypertensive older patients and can be considered a surrogate of cardiac dysfunction, resulting in decreased cardiac reserve in these patients. Also, Kobayashi et al.21 have shown that a previous history of percutaneous coronary intervention is independently associated with a decrease in CBF in hemodialysis patients. Cancer and dyslipidemia were also negatively associated with admission MAP; however; because of the broad definitions of these conditions in the NASIS it is difficult to underline their contribution to our findings.

It is noteworthy that even after adjustment for prior MI, atrial fibrillation, dyslipidemia and cancer the interaction between age and hypertension remained significantly associated with admission MAP in IS and ICH with a similar trend in TIA. Complementary to our observation, Aparicio et al.22 have shown that in a multivariate adjusted model self-measured MAP predicted stroke in patients aged ⩾60 years but not in younger patients.

An alternative explanation to our observation may be through the effect of age on autonomic activity. It has been suggested that the hypertensive response to stroke is caused by an imbalanced autonomic activity mediated by injured neurons.23 As autonomic dysfunction is related to stroke severity,24 and moderate-to-severe strokes were more common in the older population in our study, the decrease in MAP may reflect increased damage to the autonomic system. Indeed, Kvistad et al.25 reported that non-elevated admission BP was independently associated with severe stroke.

However, this explanation is unlikely as, in the fully adjusted model, stroke severity was generally not associated with admission MAP. These findings are consistent with several previous studies that showed no association between admission BP and IS severity26 or all-type stroke severity.27

Finally, the explanation of our findings may be related to stroke etiology. Marcheselli et al.28 have shown that in patients with cardioembolic stroke the acute BP response was blunted as compared with other stroke types. Compatible with that, in our study cardioembolic stroke was more prevalent at older ages (data not shown). However, the cardioembolic group in the former study consisted of a small number of patients (n=25) with a wide age range (29–89 years), so a more detailed comparison could not be carried out. Vemmos et al.29 have demonstrated a negative association between age and DBP in lacunar stroke and infarct of undetermined cause, but a potential interaction between hypertension and age was not assessed in their study.

In the present study, admission MAP was lower in patients with TIA than in those with IS or ICH, perhaps reflecting the milder underlying pathology of TIA. In addition, Fischer et al.30 have shown that acute phase SBP does not exceed average long-term premorbid SBP in 37% of IS patients and 14% of ICH patients. It can be speculated that these proportions are even larger in TIA.

Our study carries several strength points. These include its consistent methodology over medical centers and time periods, large number of patients, lack of hospital referral bias and use of a structured form for data gathering.

On the other hand, our study has some limitations. First, there were significant differences in cardiovascular risk factors, co-morbidities and stroke severity between the different age groups. Although we adjusted findings for several variables, confounding by other known or unknown risk factors cannot be ruled out. Second, the study included hospitalized patients only, therefore the generalizability of findings to stroke patients not admitted is questionable. Finally, hypertension was defined in part according to self-report and use of antihypertensive medication, which might have resulted in imprecise categorization of hypertension status.

In conclusion, we report here of a previously unrecognized association between age and admission BP in patients with stroke and TIA, in which admission MAP is lower in older hypertensive patients. As recent studies have shed light on the possible benefit of rapid BP lowering in ICH,31, 32 our findings may contribute to a more personalized 'tailored treatment' for patients with acute cerebrovascular events.

Our findings need to be validated in future large studies. Interesting areas for further research may be assessing cardiac function in hypertensive IS patients aged >75 years or the effect of different antihypertensive medications on the aforementioned pattern. Moreover, the study of associations between admission MAP and neurological outcome after stroke is an interesting topic for future studies.

References

Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, de Ferranti S, Després J-P, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Willey JZ, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB, American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015; 131: e29–322.

Rojas JI, Zurrú MC, Romano M, Patrucco L, Cristiano E . Acute ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack in the very old—risk factor profile and stroke subtype between patients older than 80 years and patients aged less than 80 years. Eur J Neurol 2007; 14: 895–899.

Qureshi AI, Ezzeddine MA, Nasar A, Suri MFK, Kirmani JF, Hussein HM, Divani AA, Reddi AS . Prevalence of elevated blood pressure in 563 704 adult patients with stroke presenting to the ED in the United States. Am J Emerg Med 2007; 25: 32–38.

Arboix A, Roig H, Rossich R, Martínez EM, García-Eroles L . Differences between hypertensive and non-hypertensive ischemic stroke. Eur J Neurol 2004; 11: 687–692.

Barron SA, Rogovski Z, Hemli J . Autonomic consequences of cerebral hemisphere infarction. Stroke 1994; 25: 113–116.

Fassbender K, Schmidt R, Mössner R, Daffertshofer M, Hennerici M . Pattern of activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in acute stroke. Relation to acute confusional state, extent of brain damage, and clinical outcome. Stroke 1994; 25: 1105–1108.

Treib J, Haass A, Krammer I, Stoll M, Grauer MT, Schimrigk K . Cardiac output in patients with acute stroke. J Neurol 1996; 243: 575–578.

Carlberg B, Asplund K, Hägg E . Factors influencing admission blood pressure levels in patients with acute stroke. Stroke 1991; 22: 527–530.

Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP, Bruno A, Connors JJB, Demaerschalk BM, Khatri P, McMullan PW, Qureshi AI, Rosenfield K, Scott PA, Summers DR, Wang DZ, Wintermark M, Yonas H, American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease, Council on Clinical Cardiology. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2013; 44: 870–947.

Morgenstern LB, Hemphill JC, Anderson C, Becker K, Broderick JP, Connolly ES, Greenberg SM, Huang JN, MacDonald RL, Messé SR, Mitchell PH, Selim M, Tamargo RJ, American Heart Association Stroke Council and Council on Cardiovascular Nursing. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2010; 41: 2108–2129.

Sandset EC, Bath PMW, Boysen G, Jatuzis D, Kõrv J, Lüders S, Murray GD, Richter PS, Roine RO, Terént A, Thijs V, Berge E, SCAST Study Group. The angiotensin-receptor blocker candesartan for treatment of acute stroke (SCAST): a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Lancet 2011; 377: 741–750.

Tetri S, Huhtakangas J, Juvela S, Saloheimo P, Pyhtinen J, Hillbom M . Better than expected survival after primary intracerebral hemorrhage in patients with untreated hypertension despite high admission blood pressures. Eur J Neurol 2010; 17: 708–714.

Cohen DL, Townsend RR . Update on pathophysiology and treatment of hypertension in the elderly. Curr Hypertens Rep 2011; 13: 330–337.

Strandgaard S . Cerebral blood flow in the elderly: impact of hypertension and antihypertensive treatment. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 1991; 4 (Suppl 6): 1217–1221.

Willie CK, Tzeng Y-C, Fisher JA, Ainslie PN . Integrative regulation of human brain blood flow. J Physiol (Lond) 2014; 592: 841–859.

Koton S, Tanne D, Green MS, Bornstein NM . Mortality and predictors of death 1 month and 3 years after first-ever ischemic stroke: data from the first National Acute Stroke Israeli Survey (NASIS 2004). Neuroepidemiology 2010; 34: 90–96.

Tanne D, Goldbourt U, Koton S, Grossman E, Koren-Morag N, Green MS, Bornstein NM, National Acute Stroke Israeli Survey Group. A national survey of acute cerebrovascular disease in Israel: burden, management, outcome and adherence to guidelines. Isr Med Assoc J 2006; 8: 3–7.

Brott T, Adams HP, Olinger CP, Marler JR, Barsan WG, Biller J, Spilker J, Holleran R, Eberle R, Hertzberg V . Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke 1989; 20: 864–870.

Jugdutt BI . Aging and heart failure: changing demographics and implications for therapy in the elderly. Heart Fail Rev 2010; 15: 401–405.

Balci K, Utku U, Asil T, Celik Y, Tekinaslan I, Ir N, Unlu E . The effect of admission blood pressure on the prognosis of patients with intracerebral hemorrhage that occurred during treatment with aspirin, warfarin, or no drugs. Clin Exp Hypertens 2012; 34: 118–124.

Kobayashi S, Mochida Y, Ishioka K, Oka M, Maesato K, Moriya H, Hidaka S, Ohtake T . The effects of blood pressure and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system on regional cerebral blood flow and cognitive impairment in dialysis patients. Hypertens Res 2014; 37: 636–641.

Aparicio LS, Thijs L, Asayama K, Barochiner J, Boggia J, Gu Y-M, Cuffaro PE, Liu Y-P, Niiranen TJ, Ohkubo T, Johansson JK, Kikuya M, Hozawa A, Tsuji I, Imai Y, Sandoya E, Stergiou GS, Waisman GD, Staessen JA, International Database on HOme blood pressure in relation to Cardiovascular Outcome (IDHOCO) Investigators. Reference frame for home pulse pressure based on cardiovascular risk in 6470 subjects from 5 populations. Hypertens Res 2014; 37: 672–678.

Qureshi AI . Acute hypertensive response in patients with stroke: pathophysiology and management. Circulation 2008; 118: 176–187.

Hilz MJ, Moeller S, Akhundova A, Marthol H, Pauli E, De Fina P, Schwab S . High NIHSS values predict impairment of cardiovascular autonomic control. Stroke 2011; 42: 1528–1533.

Kvistad CE, Logallo N, Oygarden H, Thomassen L, Waje-Andreassen U, Naess H . Elevated admission blood pressure and stroke severity in acute ischemic stroke: the Bergen NORSTROKE Study. Cerebrovasc Dis 2013; 36: 351–354.

Rossi P, Mandelli C, Manganaro D, Zecca B, Maestroni A, Monzani V, Torgano G . A spontaneous decrease of blood pressure occurs in acute ischemic stroke with favourable neurological course. Open Neurol J 2011; 5: 48–54.

Sykora M, Diedler J, Poli S, Rupp A, Turcani P, Steiner T . Blood pressure course in acute stroke relates to baroreflex dysfunction. Cerebrovasc Dis 2010; 30: 172–179.

Marcheselli S, Cavallini A, Tosi P, Quaglini S, Micieli G . Impaired blood pressure increase in acute cardioembolic stroke. J Hypertens 2006; 24: 1849–1856.

Vemmos KN, Spengos K, Tsivgoulis G, Zakopoulos N, Manios E, Kotsis V, Daffertshofer M, Vassilopoulos D . Factors influencing acute blood pressure values in stroke subtypes. J Hum Hypertens 2004; 18: 253–259.

Fischer U, Cooney MT, Bull LM, Silver LE, Chalmers J, Anderson CS, Mehta Z, Rothwell PM . Acute post-stroke blood pressure relative to premorbid levels in intracerebral haemorrhage versus major ischaemic stroke: a population-based study. Lancet Neurol 2014; 13: 374–384.

Anderson CS, Huang Y, Wang JG, Arima H, Neal B, Peng B, Heeley E, Skulina C, Parsons MW, Kim JS, Tao QL, Li YC, Jiang JD, Tai LW, Zhang JL, Xu E, Cheng Y, Heritier S, Morgenstern LB, Chalmers J, INTERACT Investigators. Intensive blood pressure reduction in acute cerebral haemorrhage trial (INTERACT): a randomised pilot trial. Lancet Neurol 2008; 7: 391–399.

Anderson CS, Heeley E, Huang Y, Wang J, Stapf C, Delcourt C, Lindley R, Robinson T, Lavados P, Neal B, Hata J, Arima H, Parsons M, Li Y, Wang J, Heritier S, Li Q, Woodward M, Simes RJ, Davis SM, Chalmers J, INTERACT2 Investigators. Rapid blood-pressure lowering in patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 2355–2365.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Hypertension Research website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Eizenberg, Y., Koton, S., Tanne, D. et al. Association of age and admission mean arterial blood pressure in patients with stroke—data from a national stroke registry. Hypertens Res 39, 356–361 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2015.147

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2015.147

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Different levels of blood pressure, different benefit from dual antiplatelet therapy in minor stroke or TIA patients

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Mean arterial pressure values calculated using seven different methods and their associations with target organ deterioration in a single-center study of 1878 individuals

Hypertension Research (2016)