Abstract

Purpose

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is a systemic vasculitis that affects medium-to-large-caliber arteries. Early diagnosis and treatment is essential as involvement of the ophthalmic artery or its branches may cause blindness. Radiographic findings may be variable and non-specific leading to delay in diagnosis. We conducted a review of the literature on neuroimaging findings in GCA and present a retrospective case series from tertiary-care ophthalmic referral centers of three patients with significant neuroimaging findings in biopsy-proven GCA.

Methods

Retrospective case series of biopsy-proven GCA cases with neuroimaging findings at the Department of Ophthalmology, Blanton Eye Institute, Houston Methodist Hospital between 2010–2015 were included in this study. Literature search was conducted using Google Scholar and Medline search engines between the years 1970 and 2015.

Results

We report findings of optic nerve enhancement, optic nerve sheath enhancement, and the first description in the English-language ophthalmic literature, to our knowledge, of chiasmal enhancement in biopsy-proven GCA. We describe four main categories of neuroimaging findings that may be seen in GCA from our series and from past cases in the literature.

Discussion

It is essential that clinicians be aware of the possible radiographic findings in GCA. Appropriate and prompt treatment should not be delayed based upon these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is a systemic vasculitis affecting medium- and large-caliber arteries.1 Ophthalmic artery involvement may cause arteritic-anterior or -posterior ischemic optic neuropathy (A-AION or A-PION), cilioretinal, or central retinal artery occlusion, or choroidal ischemia with devastating vision loss. Early diagnosis and treatment with high-dose corticosteroids is crucial. Symptoms include headache, jaw claudication, fever, weight loss, polymyalgia rheumatica, and tender temporal artery.1, 2, 3

Atypical presentations may delay diagnosis.2 Diagnosis is confirmed via superficial temporal artery biopsy (TAB) and neuroimaging is not typically necessary, but some patients in the United States frequently undergo these studies before evaluation. Unfortunately, imaging findings can be non-specific. In addition, orbital inflammatory signs and symptoms can occur, mimicking idiopathic orbital inflammatory syndrome or other infectious/inflammatory etiologies.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Furthermore, MRI abnormalities including T2 hyperintensity, diffusion-weighted imaging restriction, and gadolinium enhancement may occur in GCA-related AION or PION, broadening differential diagnosis.2, 4, 7, 8, 9, 10 Previously described MRI findings, noted in Table 1, include dural and perineural sheath enlargement, sheath and nerve enhancement, and extracranial and intracranial vascular changes.

We present neuroimaging findings in biopsy-proven GCA in three patients, review the literature on the subject, and outline four main categories of findings. To our knowledge, this is the first report of MR chiasmal enhancement in biopsy-proven GCA in the English-language ophthalmic literature.

Materials and methods

Retrospective case series of biopsy-proven GCA with neuroimaging findings at the Blanton Eye Institute, Houston Methodist Hospital between 2010–2015 were included in this study. Literature search was conducted using Google Scholar and Medline search engines between 1970 and 2015, limited to English-language and full papers. Keywords included ‘magnetic resonance imaging’, ‘giant cell arteritis’, ‘temporal arteritis’, ‘radiographic findings’, ‘enhancement’, ‘orbital findings’, and ‘orbital inflammation’. In each case, findings on TAB considered to be indicative of GCA included intimal thickening and proliferation with fragmentation of the internal elastic lamina, necrotizing vasculitis, mononuclear cell predominance, and granulomatous inflammation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was accomplished with a 3-T MRI scanner.

Case reports

Case 1

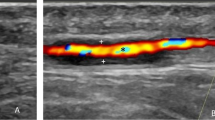

A 60-year-old Caucasian male patient presented with acute-onset headache, vision loss OS, diplopia, eye pain, and weight loss. Past medical history included hypertension and dyslipidemia. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 36 mm/h (normal <20) and C-reactive protein was 3.76 (normal <0.8 mg/l). Visual acuity was 20/40 OD and counting fingers (CFs) at 2 feet OS. There was a relative afferent pupillary defect and disc edema OS with diffuse depression, with a mean deviation of −2.13 dB on visual field testing. Slit lamp examination (SLE) revealed 1−2+ nuclear sclerotic cataract (NSC) OU consistent with 20/40 vision. MRI revealed increased signal intensity on the proximal left optic nerve with subtle enhancement (Figure 1a). TAB indicated findings consistent with resolving GCA. After intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone 1 g/day for 3 days and then oral prednisone (1 mg/kg) visual acuity improved to 20/80 OS.

Contrast-enhanced axial (a) and coronal (b) post-gadolinium T1-weighted orbital magnetic resonance imaging with fat suppression. Case 1 (top), increased signal intensity at the proximal portion of left optic nerve with subtle optic nerve enhancement (arrows). Case 2 (middle), enhancement of left optic nerve sheath (arrows). Case 3 (bottom), enhancement and enlargement of the perineural sheath of both optic nerves, as well as the chiasm (arrows).

Case 2

An 83-year-old Caucasian male patient presented with sequential loss of vision OU, complaining of orbital fullness OS. Past medical history included diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and ischemic heart disease. ESR was 5 mm/h. The patient was seen by outside ophthalmologist who initiated oral prednisone 60 mg/day.

Visual acuity was no light perception (LP) OD and CFs at 1 foot OS. Pupils were sluggishly reactive OU. SLE revealed brunescent NSC with no view of the posterior segment OD. Dilated fundus examination (DFE) showed 1+ disc pallor OS with CDR of 0.6. TAB findings were consistent with GCA, whereas MRI of brain and orbits revealed left optic nerve sheath enhancement (Figure 1b). Vision remained unchanged after steroid treatment.

Case 3

A 63-year-old Caucasian male patient presented with rapid visual loss to LP OU. Past medical history included spinal stenosis, cataracts, and hypercholesterolemia. Pupils were poorly reactive with light-near dissociation OU. SLE was normal with mild nuclear cataract OD and posterior chamber intraocular lens OS. DFE showed disc edema and fluorescein angiogram confirmed mild leakage of discs OU without choroidal involvement.

MRI showed enhancement and enlargement of the perineural sheaths of both optic nerves and the chiasm (Figure 1c). TAB demonstrated findings consistent with GCA. After treatment with IV steroid therapy followed by oral prednisone, vision improved from LP OU to CFs OD and 20/320 acuity OS. Four months after presentation, the patient’s vision was stable at CFs at 5 feet OD and 20/320 acuity OS.

Discussion

Neuroimaging is not usually required in patients with typical presentations of GCA and when performed is generally normal.11, 12 However, some patients have already undergone imaging before neuro-ophthalmic evaluation and these studies may be abnormal.

We report four main imaging findings in GCA from our cases and the literature (Table 1):

-

1

Non-specific orbital enhancement.

-

2

Optic nerve parenchymal enhancement.

-

3

Perineural sheath enhancement.

-

4

Optic chiasmal enhancement. To our knowledge, ours is the first report of MR chiasmal enhancement in biopsy-proven GCA.

Other important MRI findings in GCA include those involving the vascular supply not only extracranially but also intracranially, particularly vessel wall enhancement of the intradural ICA.13 MRI findings may hold some diagnostic value in distinguishing between A-AION as in GCA and in non-arteritic AION, in which they are typically normal, but may include a small optic nerve and chiasm volume and rarely increased proton density, STIR signal, and gadolinium enhancement.14, 15, 16 Differential diagnosis for these MRI findings can lead to inappropriate testing and delay diagnosis and treatment. Finding 1 may suggest orbital inflammatory disease, whereas Finding 2 may suggest inflammatory or demyelinating etiologies (eg, multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica, optic neuritis). Finding 3 may point to inflammatory (eg, sarcoid, granulomatous disease), infiltrative optic perineuritis, or sheath neoplasm (eg, optic nerve sheath meningioma). Finding 4 may suggest inflammatory, infiltrative, or demyelinating chiasmopathy.2, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 Clinicians should be aware of the radiographic findings in GCA and, although further testing may be required to exclude alternative etiologies, diagnosis and treatment should not be unnecessarily delayed.

References

Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ . Medium-and large-vessel vasculitis. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 160–169.

Liu KC, Chesnutt DA . Perineural optic nerve enhancement on magnetic resonance imaging in giant cell arteritis. J Neuroophthalmol 2013; 33: 279–281.

Wang X, Hu ZP, Wei L, Tang XQ, Yang HP, Zeng LW et al. Giant cell arteritis. Rheumatol Int 2008; 29: 1–7.

Chertok P, Leroux JL, Le Marchand M, Aboukrat P, Alary JC, Blotman F . Orbital pseudo-tumor in temporal arteritis revealed by computerized tomography. Clin Exp Rheumatol 1990; 8: 587–589.

Hittinger M, Berlis A, Pfadenhauer K . Inflammatory pseudo-tumour orbitae (PTO): an atypical manifestation of giant cell arteritis (GCA). Clin Neuroradiol 2015; 25: 411–414.

Laidlaw DA, Smith PE, Hudgson P . Orbital pseudotumour secondary to giant cell arteritis: an unreported condition. BMJ 1990; 300: 784.

Lee AG, Tang RA, Feldon SE, Pless M, Schiffman JS, Rubin RM et al. Orbital presentations of giant cell arteritis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2001; 239: 509–513.

Morgenstern KE, Ellis BD, Schochet SS, Linberg JV . Bilateral optic nerve sheath enhancement from giant cell arteritis. J Rheumatol 2003; 30: 625–627.

Lee AG, Eggenberger ER, Kaufman DI, Manrique C . Optic nerve enhancement on magnetic resonance imaging in arteritic ischemic optic neuropathy. J Neuroophthalmol 1999; 19: 235–237.

Reddi S, Vollbracht S . Giant cell arteritis associated with orbital pseudotumor. Headache 2013; 53: 1488–1489.

Osman SS, Amin A . Value of MRI in diagnosis of giant cell arteritis. Neurol Asia 2012; 17: 369–372.

Khanna S, Sharma A, Huecker J, Gordon M, Naismith RT, Van Stavern GP . Magnetic resonance imaging of optic neuritis in patients with neuromyelitis optica versus multiple sclerosis. J Neuroophthalmol 2012; 32: 216–220.

Siemonsen S, Brekenfeld C, Holst B, Kaufmann-Buehler AK, Fiehler J, Bley TA . 3T MRI reveals extra- and intracranial involvement in giant cell arteritis. Am J Neuroradiol 2015; 36: 91–97.

Biousse V, Newman NJ . Ischemic optic neuropathies. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 1677.

Kerr NM, Chew SS, Danesh-meyer HV . Non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy: a review and update. J Clin Neurosci 2009; 16: 994–1000.

Rizzo JF, Andreoli CM, Rabinov JD . Use of magnetic resonance imaging to differentiate optic neuritis and nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Ophthalmology 2002; 109: 1679–1684.

Nielsen NV, Eriksen JS . Unusual ocular manifestation in temporal arteritis. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1979; 57: 362–368.

Nassani S, Cocito L, Arcuri T, Favale E . Orbital pseudotumor as a presenting sign of temporal arteritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 1995; 13: 367–369.

Joelson E, Ruthrauff B, Ali F, Lindeman N, Sharp FR . Multifocal dural enhancement associated with temporal arteritis. Arch Neurol 2000; 57: 119–122.

Cockerham Kimberly P., Cockerham GC, Brown HG, Hidayat AA . Radiosensitive orbital inflammation associated with temporal arteritis. J Neuroophthalmol 2003; 23: 117–121.

Atlas SW . Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain and Spine. Volume 14th edn Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2009.

Newman NJ, Lessell S, Winterkorn JMS . Optic chiasmal neuritis. Neurology 1991; 41: 1203–1203.

Liu TY, Miller NR . Giant cell arteritis presenting as unilateral anterior ischemic optic neuropathy associated with bilateral optic nerve sheath enhancement on magnetic resonance imaging. J Neuroophthalmol 2015; 35: 360–363.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

D'Souza, N., Morgan, M., Almarzouqi, S. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in giant cell arteritis. Eye 30, 758–762 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.19

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2016.19

This article is cited by

-

Orbital magnetic resonance imaging of giant cell arteritis with ocular manifestations: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis

European Radiology (2023)

-

Utility of standard diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging for the identification of ischemic optic neuropathy in giant cell arteritis

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Intraorbital findings in giant cell arteritis on black blood MRI

European Radiology (2022)

-

Beyond Giant Cell Arteritis and Takayasu’s Arteritis: Secondary Large Vessel Vasculitis and Vasculitis Mimickers

Current Rheumatology Reports (2020)