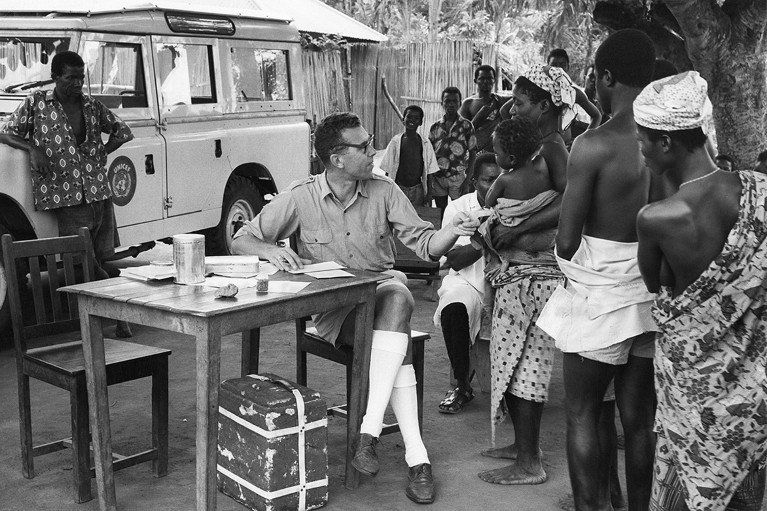

In the late twentieth century, physicians in Togo collected data to gauge the success of campaigns carried out against the skin disease yaws.Credit: GRANGER Historical Picture Archive/Alamy Stock Photo

In 1980, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced the successful eradication of smallpox — the first and only human infectious disease to be stamped out. But before smallpox was on the WHO’s eradication docket, there was yaws.

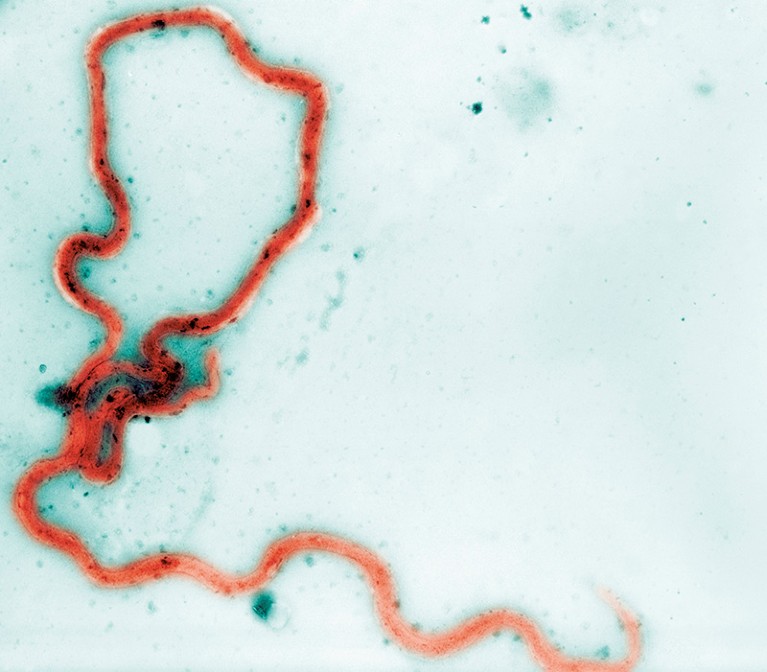

Yaws is a skin disease caused by the corkscrew-shaped bacterium Treponema pallidum subsp. pertenue, a close relative of other Treponema bacteria, including those that cause syphilis. A yaws infection begins with wart-like tumours on the skin that turn into ulcers. Bacteria from the ulcers can spread between people through direct skin contact and, although lesions might heal without treatment, the bacterium can then lie dormant in the body for years. If it re-emerges, it can cause painful inflammation and destruction of bone and surrounding tissue, which can lead to disability in 10% of cases1. In 2012, the WHO, encouraged by research on a new treatment, committed to eradicating yaws by 2020. But, there are still thousands of cases being reported today.

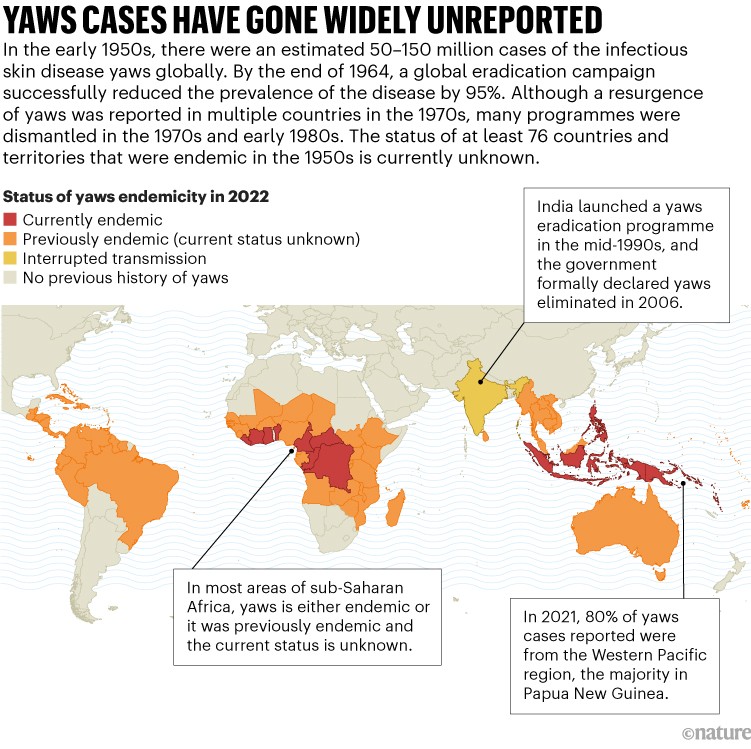

Yaws mostly affects children in rural, low-income communities in tropical areas of Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Pacific (see ‘Yaws cases have gone widely unreported’). “Such a chronic, disfiguring and debilitating childhood infectious disease is very disturbing for them in their learning,” says Lydia Sahamie, a community health-care worker in Papua New Guinea, where the majority of cases are being reported today.

Treponema pallidum subsp. pertenue is a spiral-shaped bacterium that causes the skin disease yaws.Credit: Cultura Creative RF/Alamy Stock Photo

Efforts to control and eliminate yaws go back decades. “Since the WHO was established in 1948, yaws has been on the agenda,” says Kingsley Bampoe Asiedu, who grew up in Ghana — where yaws is endemic — and is now a medical officer in the Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases at the WHO in Geneva, Switzerland. From the early 1980s until now, targeted intervention campaigns in endemic areas have focused on preventative measures to reduce transmission — including community education on the importance of personal hygiene — as well as improving diagnoses and access to treatment. Just one dose of an inexpensive oral antibiotic called azithromycin can clear the yaws-causing bacterium from the person’s system, allow their ulcers to heal and reverse inflammation. “How big is the injustice that these kids do not have a 20 cent medicine?” says Oriol Mitjà, an infectious-disease physician and researcher at Germans Trias i Pujol University Hospital in Barcelona, Spain.

Although campaigns have brought some success, impediments that have existed for decades still remain — including a lack of resources to reach and treat people in remote areas and to monitor the disease. New challenges have also emerged.

Part of Nature Outlook: Neglected tropical diseases

“The story has gotten a lot more complicated in the last five years,” says global public-health researcher Camila González-Beiras at Germans Trias i Pujol University Hospital, who also leads fieldwork on Lihir Island, Papua New Guinea. Cases of antibiotic resistance emerged in 2020, as has evidence that our primate relatives harbour the same yaws-causing bacterium — opening up the possibility that yaws could reinfect people even if eradication in humans is successful. Furthermore, there are many infections that can cause ulcers that are similar in appearance to yaws, which makes diagnoses more difficult, says González-Beiras.

Nevertheless, yaws remains one of just two WHO neglected tropical disease eradication targets for 2030. At first glance that might sound like the organization is moving the goalposts and might raise questions about why the 2030 target is any more realistic than the now-passed 2020 one. But researchers and public-health workers are cautiously optimistic that this time, the goal is within reach, thanks to advances in treatment options and continuing work to make more accurate diagnoses and surveillance possible.

From penicillin to vaccines

In 1952, the first yaws eradication campaign was launched, and injections of penicillin-based antibiotics were given out across the world. “They treated 50 million people for yaws and reduced the global burden of disease by 95%,” says Michael Marks, an infectious-disease physician and researcher at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. “If that initial campaign didn’t have the ‘E’ word attached to it, it would have been counted as a stunning public-health success.”

The last mile of the eradication journey is often the most difficult, Marks says, because “as something becomes less of a burden, it becomes more difficult to prioritize it”. With waning resources and a lack of surveillance, there was a resurgence of yaws in the 1970s.

The bacterial infection yaws begins with wart-like tumours on the skin.Credit: Graeme Williams/Panos Pictures

The next big push to get rid of yaws came in 2012, following the work of Mitjà and his colleagues, who showed that a single dose of azithromycin could be used in place of penicillin2. Compared with penicillin, azithromycin is easier to obtain, transport and administer — it’s given as a tablet, or occasionally a syrup, so it does away with the discomfort of an injection and does not require administration by health-care workers.

But as 2020 came to a close, there were still more than 300 confirmed cases and more than 80,000 clinically suspected cases of yaws worldwide. Even more ominously, in October of that year, Mitjà, González-Beiras, Marks and their colleagues published data on the first cases of azithromycin-resistant yaws — a development that threatened to neutralize what had become the most powerful weapon against the disease3.

Fortunately, penicillin is still an effective fall back option in cases of azithromycin resistance. And further options are on the way. In particular, a drug called linezolid is being evaluated in a clinical trial in Papua New Guinea. Similar to azithromycin, linezolid is a tablet that is easy to transport and administer. “So far it looks really promising,” says Gonzáles-Beiras, who is leading the trial. Last year, Mitjà, Marks, González-Beiras and their colleagues also reported the results of an updated treatment approach that could reduce cases further. They found that administering three rounds of mass treatment of azithromycin to everyone in a community at six-month intervals, compared with a conventional single round followed by targeted treatment, led to a significant reduction in yaws cases4.

Children wait their turn to participate in a yaws screening and treatment intervention as part of a clinical trial on Lihir Island, Papua New Guinea.Credit: Dr Camila González Beiras

Even better would be a yaws vaccine, which would reduce the need for antibiotics altogether. Although there is no vaccine specifically for yaws in development, some researchers are working on a syphilis vaccine. The Treponema bacteria that cause yaws and syphilis are nearly identical, so a syphilis vaccine could offer cross-protection for yaws.

Creating a vaccine for either infection is a challenge, because a protein on the microbe’s outer coat that would be targeted by a vaccine, called the TprK antigen, is constantly changing5. “There are literally millions of permutations of how this protein can look. So the immune response simply can’t keep up with it,” says Sheila Lukehart, a retired global-health researcher at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Tools for tracking

In the absence of a vaccine, the next best weapon to wipe out yaws is to accurately diagnose and treat people and then continue to carefully track cases. “To do a clinical diagnosis just by the look of the ulcer is incredibly difficult,” says González-Beiras. And if ulcers are mistaken as yaws but don’t respond to azithromycin treatment, she adds, it could negatively affect the social perception of these interventions and “jeopardize the progress of eradication”.

Blood tests are available that can determine whether a person is infected with a Treponema bacterium (or has been previously) but, even then, not all Treponema respond to azithromycin. Multiple strains of Treponema that cause syphilis are azithromycin resistant. Identifying precisely which bacterium is causing the ulcer requires molecular testing. Unfortunately, these tests fare poorly in the heat of the tropics because many reagents need to be kept refrigerated, so samples must be sent off for sequencing, and results don’t come back until long after a person is treated, possibly ineffectively. Researchers are designing hardier test alternatives that would allow for the samples to be analysed closer to a treatment site, such as loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), which uses reagents and equipment that are less sensitive to heat6. But, so far, none of these approaches have been shown to be particularly reliable, says González-Beiras.

Source: WHO

For disease surveillance to succeed, cases of yaws will need to be identified quickly and accurately — and that’s not happening. Today there are 15 countries with reported cases of yaws, but that’s probably an undercount. Decades ago, many countries stopped reporting cases to the WHO. There are at least 76 previously endemic countries where the status of the disease is unknown, which Marks says raises the question of whether “absence of evidence is the same as evidence of absence”?

Tracking human cases of yaws is challenging enough, but the confirmation that the pathogen also infects some of our closest animal relatives poses another surveillance hurdle.

The primate reservoir

For nearly a century, it was thought that humans were the exclusive host of the bacterium that causes yaws. But in 2018, Sascha Knauf, director of the Institute of International Animal Health/One Health in Greifswald, Germany and his colleagues found that non-human primates harbour the same bacterium7.

There is currently no evidence that T. pallidum subsp. pertenue has ever spilled over from non-human primates to humans. But that’s far from a guarantee against such transmission in the future. Other neglected tropical diseases that were also once thought to be present only in humans were later found to infect other animals as well. “If you went back to 1990, people didn’t think that dogs were important in the transmission of Guinea worm,” says Marks. But now it’s known that dogs are in fact an important reservoir for the parasite that causes this severe, painful infection.

In 2018 it was reported that non-human primates, including green monkeys (Chlorocebus sabaeus), harbour the bacterium that causes yaws.Credit: Olena Shvets/Getty

“In the areas where humans co-exist with infected non-human primates, we have to continue surveillance,” says Knauf, even if we were to eliminate yaws in humans. “If it spills over — and if there is no surveillance — it will mean you miss it and then in 10 or 20 years you’ll likely see human cases again.”

Effective treatments, diagnostics and surveillance are just part of the eradication equation. “You may have the tools,” says Asiedu, “but getting the tools to those in need is a challenge.”

Reaching remote communities

Those who need help are certainly receptive to it, says Nana Konama Kotey, who heads Ghana’s yaws eradication programme in Accra — even in places where both the general population and health-care workers lack awareness and knowledge of yaws. That makes her even more optimistic about elimination in Ghana specifically. “Assuming we have 100 communities, maybe one will refuse,” she says, “and then we try and correct whatever misconceptions they have.”

The main hurdle, Kotey says, is to secure the funding needed to diagnose and treat target populations. “The biggest cost in a lot of campaigns is reaching people,” echoes Marks. In an unfortunate paradox, success in anti-yaws campaigns can undermine support. Funders and public-health organizations that are eager to support efforts in remote areas where there are hundreds or thousands of cases tend to lose interest when the case numbers dwindle to a handful.

Crucial for goal-setting in the yaws eradication effort, says González-Beiras, is a better understanding of what is possible to achieve in communities. Many of the guidelines and protocols issued by well-meaning organizations, she says, come across as oblivious to the realities on the ground. These documents include language about hospitals and health-care centres — but such establishments, and even treatment facilities with electricity, can be rare in places such as Papua New Guinea.

Infectious-disease physician Oriol Mitjà treats children with yaws in Papua New Guinea.Credit: Graham Jepson

In addition to setting goals in line with the resources available, maintaining surveillance to ensure eradication means building a local workforce to continue with these efforts in places where yaws is endemic, says González-Beiras. “You can do all of these helicopter interventions where you come and give antibiotics to everyone — but what’s going to happen in six months, two years, five years, ten years?”

That’s where people like Sahamie and Kotey play such crucial parts. In Ghana, Kotey is not only involved in developing comprehensive plans and strategies for the elimination of yaws, but is also facilitating collaboration among government departments, health-care providers, community leaders and non-profit organizations. In Papua New Guinea, alongside González-Beiras, Sahamie — currently a student at Divine World University's St Mary's School of Nursing in Vunapope, Papua New Guinea — is helping with the linezolid drug trial.

“When you land in Papua New Guinea, there is this huge banner that says, ‘The land of the unexpected’, and it couldn’t be more true,” says González-Beiras. “Anything can happen. There are so many variables. There are so many cultural differences.” It takes years to grow a network and gain trust, she says, “but once you’re in, you’re in”. Today, González-Beiras has hope for Papua New Guinea because of local people such as Sahamie, who began yaws elimination work with little previous training. “They are managing the whole project right now themselves,” says González-Beiras, from her laboratory in Spain. “They are doing an amazing job.”

Tropical diseases move north

Tropical diseases move north

Mental health: The invisible effects of neglected tropical diseases

Mental health: The invisible effects of neglected tropical diseases

In search of a vaccine for leishmaniasis

In search of a vaccine for leishmaniasis