Science will have a front-row seat at the United Nations meetings in New York City this week.Credit: Eduardo Munoz Alvarez/VIEWpress/Getty

This week, New York City is buzzing with scientists. A Science Summit is being held at the United Nations, to coincide with the UN General Assembly. The summit’s overall theme revolves around the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which aim to end poverty and protect the environment.

Research is crucial for all of the goals, as the Nature Portfolio of journals has been reporting in a series of editorials on the SDGs — from improving how the goals’ smaller targets are measured to designing evidence-based methods to achieve them. So far, none of the SDGs is on track to being achieved by the 2030 deadline. To spur science that will help to accomplish the goals, summit organizers are keen to build more research collaborations, across nations and between scientists working in different sectors — universities, businesses, governments and campaign groups.

Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals

Science is explicitly recognized in two of the goals: international partnerships are a theme of SDG 17; and SDG 9 includes targets to increase spending on research and development as well as expand the number of researchers. But for the world to truly benefit, science-funding agencies in high-income countries need to place a much stronger emphasis on the SDGs for projects they fund.

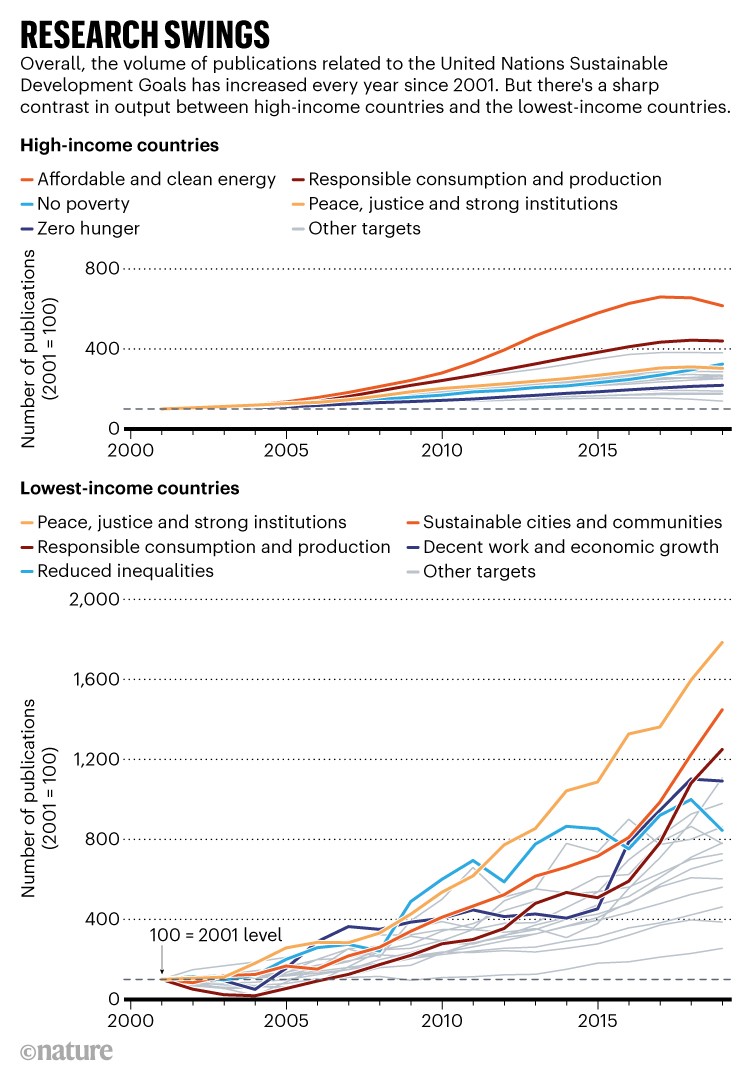

Low-income countries spend about 0.5% of their gross domestic product on science, whereas high-income countries spend around 3%. But research in low-income countries is much more likely to be aligned with the goals: 60–80% of these nations’ scientific publications have some connection to the SDGs, compared with 30–40% in upper-middle and high-income ones (see ‘Research swings’). This contrast was highlighted two years ago by the UN science and cultural organization UNESCO, and its report was followed by a 2022 study by researchers at the University of Sussex near Brighton, UK, University College London and the United Nations Development Programme based in New York City. It is hugely encouraging that the poorest countries embrace the SDGs in research, yet it will not have the desired impact because low-income nations accounted for just 0.2% of globally produced science at the time of the study (see go.nature.com/44r28yw).

Adapted from: Changing Directions: Steering Science, Technology and Innovation towards the Sustainable Development Goals

In July, the International Science Council, a Paris-based network representing research academies around the world, published a report appropriately called Flipping the Science Model that was co-chaired by New Zealand’s former prime minister Helen Clark and UNESCO’s former director-general Irina Bokova (see go.nature.com/48aozg6). Science is mainly funded through national budgets and is often led by influential investigators.

The report’s authors propose that countries also create a global fund (worth US$1 billion). Proposed projects would be assigned to regional ‘hubs’, enabling researchers to collaborate across borders on global challenges. Studies would be designed by both scientists and affected stakeholders — ensuring that communities are included in the process as partners and that they benefit from the outcomes. The current UN Science Summit similarly heard repeated calls for a global research agenda.

What scientists need to do to accelerate progress on the SDGs

This re-prioritization of funding will need both governments and national funding agencies to think more globally, and to not see national priorities as competing with global ones. The European Union provides one model for how this could be done. EU member states have their own research programmes, but they also contribute to the EU Horizon Europe research-funding scheme (worth around $100 billion between 2021 and 2027), which explicitly prioritizes international collaborations on global challenges. As of 2022, the fund had disbursed more than $10 billion to 39,000 researchers in 142 countries. Although 39% of grant recipients are from universities, 29% are from businesses — all working together on projects in health, inclusive societies, climate, energy and food.

SDG advocates must now deepen conversations with national and regional science-funding agencies. Some do not see the SDGs as a priority; others think there are obstacles that are too difficult to tackle. Designing collaborative and participatory funding schemes will be complex, but funding agencies as well as researchers should remember that the SDGs are not optional. If the world doesn’t meet them, the consequences will be severe and their progress is everyone’s responsibility.

Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals

Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals

What scientists need to do to accelerate progress on the SDGs

What scientists need to do to accelerate progress on the SDGs

How much progress are we making on the world’s biggest problems? Take this quiz on plans to save humanity

How much progress are we making on the world’s biggest problems? Take this quiz on plans to save humanity

The world’s goals to save humanity are hugely ambitious — but they are still the best option

The world’s goals to save humanity are hugely ambitious — but they are still the best option