This year marks the halfway point of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which were agreed in 2015, to be reached by 2030. As an independent group of scientists appointed by the UN to assess progress and recommend how to move forwards, we have a stark message: the world is not on track to achieve any of the 17 SDGs and cannot rely on change to happen organically.

At the current rate of progress, the world will not eradicate poverty, end hunger or provide quality education for all by 2030 — to name just some, central, aspirations of the SDGs. Instead, by the end of this decade, our world will have 575 million people living in extreme poverty, 600 million people facing hunger, and 84 million children and young people out of school1. Humanity will overshoot the Paris climate agreement’s 1.5 °C ‘safe’ guardrail on average global temperature rise. And, at the current rate, it will take 300 years to attain gender equality2.

The world’s goals to save humanity are hugely ambitious — but they are still the best option

Global leaders must act now to remove roadblocks and accelerate progress. This is the focus of our Global Sustainable Development Report (GSDR), launched this week, ahead of the SDG Summit in New York City under the auspices of the UN General Assembly. This independent scientific assessment, made every four years, involved global consultations to collect perspectives across regions and synthesize scientific evidence from across disciplines. It has been peer reviewed by 104 researchers with expertise in areas ranging from human well-being and economics to food, energy, cities and natural resources.

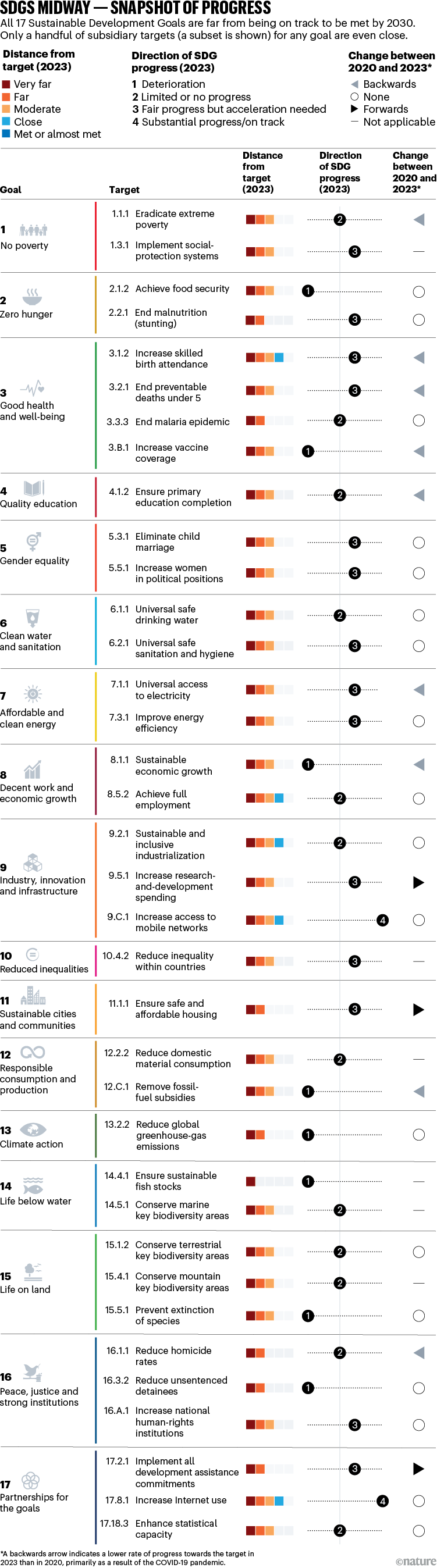

Of the 36 SDG targets reviewed in the GSDR to provide a snapshot of progress3, only two were on track as of 2023, namely access to mobile networks and internet usage (see ‘SDGs Midway — Snapshot of Progress’). Fourteen showed ‘fair’ progress, with targets just in reach if efforts are stepped up. Twelve showed limited or no progress, including for poverty, safe drinking water and ecosystem conservation. And eight targets were assessed as still deteriorating: reducing greenhouse-gas emissions, fossil-fuel subsidies and numbers of unsentenced detainees; enhancing economic growth, vaccine coverage, sustainable fishing and food security; and preventing the extinction of species.

Source: Ref. 3

There have been some bright spots: growing public awareness, some government and corporate commitments to reaching the SDGs, and political discussions around them. But these have been to little concrete effect. So far, there have been no profound changes to institutions and legislation4, and the landscape of investments and resources hasn’t altered significantly. Even modest progress, such as a fall in child mortality and improvements in gender-equality targets, has been slowed or reversed in recent years.

Although global and regional crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine have played a part in that, our analysis shows that the lack of headway is largely a direct result of inaction by governments. Insufficient financial resources and weak administrative capacities hamper progress in many countries. Ingrained habits and lifestyles promoted by sophisticated marketing campaigns make it hard to shift behaviours towards sustainable diets, transport and consumption patterns. Existing investments in capital, such as fossil-fuel infrastructure, have generated resistance from vested interests and made climate action politically sensitive.

Moving the deadline back by a decade or two won’t help — on the current trajectory, model projections suggest that the world will not achieve any of the SDGs even by 20505. The response must be to double down and strengthen efforts. Achieving the SDGs requires much more than niche innovations; it will take wholesale systemic transformations in areas ranging from how water is managed to how food is grown. It’s crucial that scientists support policymakers and others in rethinking institutions, systems and practices. Here we highlight three priority areas: removing roadblocks to progress; identifying transformation pathways; and improving governance.

Identify tailored approaches to remove key roadblocks to progress

To break the logjam, scientists need to find out what is impeding system-wide changes in different places and sectors, and identify rapid ways to overturn those obstacles. Most research of the dynamics of transformations has so far focused on a few sectors, such as energy, and predominantly on high-income nations. The lessons are difficult to transfer to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) or to other goals, such as education, poverty or biodiversity.

Many instruments for enabling change are well known. For example, government investments in research and development (R&D), and in subsidies and incentives for sustainable technologies and practices, have brought down the cost of renewable energy hugely; the price of solar cells, for example, has declined 100-fold. But this has taken four decades. If the world is to accelerate progress, governments need to play a more active part, by stimulating innovation, shaping markets and regulating business. Precisely how depends on local contexts.

Reducing environmental hazards, such as air pollution, also benefits human health.Credit: Beawiharta/Reuters

For example, it might be more politically feasible to transition to net-zero emissions in service-based economies, such as Switzerland and Singapore, than in economies with large fossil-fuel-based assets such as Australia and many Middle Eastern countries. Governments of LMICs might be ready to support a clean-energy transition if it provides better access to cheap power, but might lack the finance, supporting infrastructure or institutions needed to make it happen.

Every nation and sector will need a tailored approach for navigating such major transitions. To help them, researchers should provide evidence on the optimal routes to substantial and rapid changes in technologies, policies and behaviours. Ideally, the mix of interventions would reinforce one another to trigger positive change across many SDGs.

Bucking the system: the extraordinary story of how the SDGs came to be

For example, to shift societies towards a diet that is also healthy for the planet6, one approach could be for governments to invest first in R&D to develop cost-effective alternative foods, then use public money to buy them, and deploy market incentives and awareness campaigns to encourage uptake and boost commercial viability. They should also use market interventions such as taxes and regulations to scale up adoption quickly.

Research on positive tipping points should also be harnessed and expanded. For example, enabling solar and wind energy to reach price-parity with fossil-fuel energy has flipped investment incentives towards low-carbon energy — which will account for around 90% of investment in power generation in 2023. Less is known about tipping points in other sectors. Factors beyond cost need to be better understood — solutions need to be more attractive in their functionality, reliability, accessibility and cultural appeal.

For example, countries such as Norway have managed to bring forwards the price-parity tipping point for electric vehicles through targeted subsidies, including tax and other cost exemptions7. The success of these measures has also relied on large investments in charging infrastructure to improve reliability and accessibility. The market share of battery electric vehicles in Norway rose from less than 1% in 2010 to close to 80% last year.

Twelve of a subset of 36 SDG targets had seen little or no progress in a recent assessment, including the target of providing safe drinking water for all.Credit: Zuma/eyevine

There will be ongoing obstacles to change. Uptake of electric vehicles might stall if supporting infrastructure is lacking or policy support is withdrawn owing to a backlash from change-averse car makers. More-stringent policies such as phasing out fossil-fuel cars or coal-fired power stations can face resistance from powerful interest groups. Incoming technologies and practices in one SDG area can have downsides in others. For example, mining critical minerals for batteries damages the environment, and the decline of jobs in fossil-fuel sectors can affect livelihoods in some communities.

Researchers need to study ways to build momentum for tougher interventions, overcome resistance to change and manage negative side effects. This will require more support from funders, research institutions and publishers to promote and feature research on the SDGs, especially to study goals that are lagging, such as on equality and the environment, and how to boost progress in LMICs.

Find feasible and cost-effective pathways

Although sustainable energy and food-system transitions have featured strongly in recent research, little is known about policy pathways that aim to achieve all the SDGs simultaneously. Policymakers need practical guidance on cost-effective interventions as well as managing trade-offs.

‘We are killing this ecosystem’: the scientists tracking the Amazon’s fading health

Models have shown how addressing the SDGs together can be beneficial, especially around energy, the economy, climate and land, for which coupled models are already well developed. For example, many SDGs could be achieved by 2050 through more-ambitious action5. This would include a mix of interventions, such as a price on carbon, redistribution of carbon revenues to alleviate poverty, increasing the supply of clean energy while phasing out coal, electric-vehicle mandates, a transition to sustainable diets, protection for biodiversity hotspots, and efficiency improvements in irrigation and fertilizer use.

For human-development goals, scaling up investments in social policies would help8. For example, doubling budgets for public health, social welfare, education, R&D and infrastructure along with improvements in participatory governance and control of corruption could, by 2030, lift 124 million more people out of poverty and leave 113 million fewer malnourished.

Researchers need to examine feedbacks, synergies and trade-offs to help inform coherent strategies that make the best use of available resources and manage unintended side effects. For example, investments in health and education can improve economic productivity and growth, people’s incomes and government revenue, yet they could also increase consumption and thus resource demand, environmental degradation and pollution, as well as exacerbating inequalities. Equitable energy-transition programmes typically seek to reduce emissions, provide energy security, access and affordability, and create jobs, but they also need to navigate new potential risks in land use and supply chains.

Boosting clean energy supports many SDGs.Credit: Chandan Khanna/AFP via Getty

Identifying sweet spots, in which the greatest benefits could be gained with the most-cost-effective solutions, would help to use resources as judiciously as possible. A modelling study in Tanzania9 shows how subsidies for photovoltaics would enable progress on affordable and clean energy, while also supporting other goals — such as education by allowing students to study longer, health by reducing air pollution from solid fuels, and climate action by reducing emissions.

Policymakers want national detail about actions and costs. For example, modelling in Australia10 shows that quick gains can be made on 52 SDG targets by following a green-economy pathway. This would include investing an extra 1% of gross domestic product (GDP) annually to improve energy and water efficiency, and support sustainable agriculture and transport, renewable energy and biodiversity protection. It could be financed through taxes on consumption. In addition to the green investment, spending an extra 2.5% of GDP per annum on health, education and social subsidies and transfers, along with policies to address inequality, would boost average progress on the SDGs to 70% by 2030. This compares to just 42% progress if governments focus only on delivering more-rapid economic growth.

However, it has proved hard to translate analytical exercises into policy advice because the studies have not always involved policymakers, and the methods and results might remain too high-level or abstract, or unlinked to policy processes. One way to bridge this gap would be to embed SDGs analyses in existing assessments of major policy reforms, new legislation or big programmes or public investments. For example, guidelines adopted in Denmark require that new government bills be screened and assessed to evaluate their consequences for achieving the SDGs.

Governments and businesses should review their structures and processes (regulatory, budgeting, planning and auditing) to identify areas in which SDG analyses are needed. National systems should also be enhanced, particularly in LMICs — for example, by setting up cross-governmental coordination offices and expert units for generating, synthesizing and packaging specialized evidence11.

Strengthen governance and accountability

SDG progress relies on the effectiveness of governance processes, but these span a wide spectrum. What’s more, the SDGs are not legally binding and every nation, sector and other stakeholder has engaged with them in its own ways. Myriad processes have sprung up, including Voluntary National Reviews (VNRs) and Voluntary Local Reviews, to track and report progress on the SDGs. These reviews are undertaken by national or local authorities to report on progress and share experiences, successes and lessons learnt in implementing the SDGs.

The VNRs are presented annually to the UN High-level Political Forum for Sustainable Development in New York City, which reviews SDG commitments and provides a forum for countries to share best practices. But accountability from governments remains weak — expressed political support for the SDGs has often failed to translate into strategic public policy processes, especially long-term budgets and investment. For example, a review of national budgets in 74 countries showed that only 13 had integrated the SDGs into budget lines or allocations12. The effectiveness of SDG processes, policies and strategies has also received little scientific validation.

Progress on ensuring global food security has actually been backwards.Credit: Caren Firouz/Reuters

Scientists need to develop criteria to assess the impact of different SDG governance processes. Policies, processes and programmes need to move from being ‘accommodative’ — the equivalent of painting SDG targets on to existing strategies — to ‘transformative’, with norms and structures redesigned to align with SDG outcomes13. Stronger action would probably result if the SDGs were fully integrated into strategic planning, legislative and budget processes. For example, Mexico and Colombia have linked their national budgets to the SDGs to improve alignment of expenditure with outcomes. This provides opportunities for researchers to evaluate whether such approaches result in tangible improvements.

Researchers should also provide guidance to enhance accountability — for example, by providing systematic and empirical insights on the design of effective national accountability mechanisms for the SDGs. These are highly context specific, but might use parliamentary inquiries, auditing agencies or human-rights institutions to evaluate the adequacy of implementation and provide recommendations. Countries could also embed the goals in legislation or include them in the mandates for existing independent and ongoing reporting institutions and initiatives.

For example, national supreme audit institutions in the Netherlands, Lithuania and Tanzania have evaluated and provided recommendations to their governments on preparedness for implementing the SDGs. Finland uses several mechanisms to increase accountability, including a national multi-stakeholder sustainable-development commission and an annual citizens’ panel on sustainable development, and is developing an approach to apply the SDGs to all relevant national audits. Popularizing the goals can also increase government interest and social accountability.

Without accelerated action, the ambitious plan that the world signed up to in 2015 will fail. Scientists, institutions and funders must do their part to save the SDGs — and the planet and human society.

The world’s goals to save humanity are hugely ambitious — but they are still the best option

The world’s goals to save humanity are hugely ambitious — but they are still the best option

How much progress are we making on the world’s biggest problems? Take this quiz on plans to save humanity

How much progress are we making on the world’s biggest problems? Take this quiz on plans to save humanity

Bucking the system: the extraordinary story of how the SDGs came to be

Bucking the system: the extraordinary story of how the SDGs came to be

‘We are killing this ecosystem’: the scientists tracking the Amazon’s fading health

‘We are killing this ecosystem’: the scientists tracking the Amazon’s fading health

Water pollution ‘timebomb’ threatens global health

Water pollution ‘timebomb’ threatens global health

How to reduce Africa’s undue exposure to climate risks

How to reduce Africa’s undue exposure to climate risks

Millions of jobs in food production are disappearing — a change in mindset would help to keep them

Millions of jobs in food production are disappearing — a change in mindset would help to keep them

Shade is an essential solution for hotter cities

Shade is an essential solution for hotter cities

Degrowth can work — here’s how science can help

Degrowth can work — here’s how science can help

How to stop cities and companies causing planetary harm

How to stop cities and companies causing planetary harm