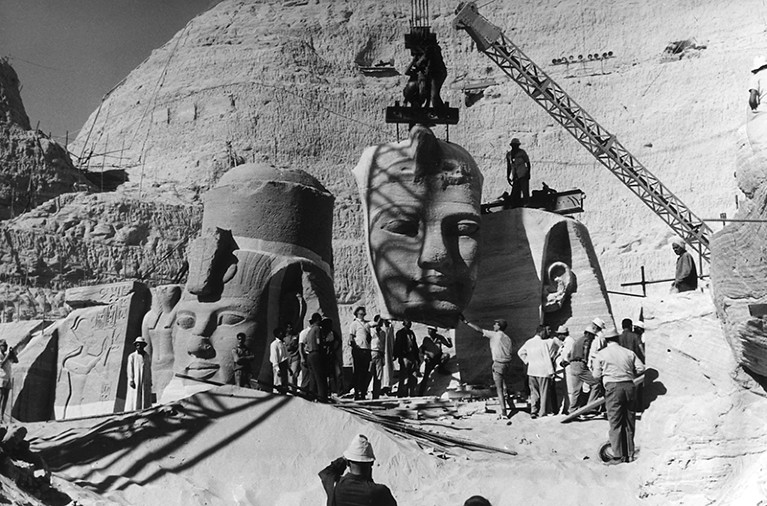

Workers move part of a statue during the relocation of the Abu Simbel temples in Egypt in the 1960s.Credit: UNESCO

A Future in Ruins: UNESCO, World Heritage, and the Dream of Peace Lynn Meskell Oxford University Press (2018)

In 1945, three months after the end of the Second World War, delegates from 44 countries gathered in London. Britain’s prime minister, Clement Attlee, told the conference that “the peoples of the world are islands shouting at each other over seas of misunderstanding”. The delegates proposed another way: the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The agency, based in Paris, was dedicated to preserving peace by promoting the international exchange of ideas. Its first director-general was the British biologist, humanist and amateur archaeologist Julian Huxley.

In A Future in Ruins, archaeologist Lynn Meskell offers an institutional ethnography of UNESCO. The organization’s broad remit ranges from publishing to promoting women in science, but Meskell focuses exclusively on its role in protecting world heritage and archaeology, particularly through the 1972 World Heritage Convention. Inevitably, this role has been highly political. UNESCO’s mission was “to end global conflict and help the world rebuild materially and morally”, Meskell observes. Yet increasingly, she argues, its efforts are caught up in the proliferation and prolongation of local conflicts and tensions.

Witness the World Heritage sites at, for instance, Angkor in Cambodia; Bodh Gaya in India; Kandy in Sri Lanka; Palmyra in Syria; and Timbuktu in Mali. The 1992 inscription of Angkor in the World Heritage List was supported by exiled sympathizers of the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime, hoping to bolster territorial claims. As nations jostle on and around UNESCO’s committee to achieve listing, it is clear that designation is about more than past glory. It is also a way of ensuring future rewards, most obviously the boosting of tourism.

The daunting nature of the agency’s goal was obvious from the start. Huxley was under no illusions about it, referring to the “impossibility of UNESCO producing the rabbit of political peace out of a cultural and scientific hat”. In 1948, Huxley was eased out of office at the behest of the US delegation (possibly owing to his left-wing humanism). Classicist Gilbert Murray subsequently predicted that UNESCO was destined to be “a confused mixture of success and failure”. He had a unique perspective. From 1922 to 1939, he had served on the agency’s predecessor, the League of Nations’ dispute-ridden International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation, which included scientific luminaries Marie Curie, Albert Einstein and Hendrik Lorentz. As Meskell concludes, Murray’s prediction rings true seven decades on.

Nonetheless, UNESCO’s successes have been impressive. It came to the rescue of Venice in 1966, when devastating flooding threatened swathes of the Italian city’s cultural treasures, valued at US$6 billion. Under the agency’s auspices, Japan funded and directed the restoration of Indonesia’s Buddhist temple of Borobudur. Its greatest triumph is probably still its much-publicized 20-year Nubian campaign. Launched in 1959, this aimed to rescue ancient Egyptian and Sudanese sites from flooding, caused by the 1960–70 construction of the Aswan High Dam on the Nile. Meskell devotes an informative chapter to this extraordinary feat. Some 23 temples, tombs, early Christian churches and rock-hewn chapels were dismantled and relocated — most famously the temple of Rameses the Great at Abu Simbel, at a cost of $70 million.

Buddhist monks in the Angkor Wat temple, Cambodia, which has been a World Heritage site since 1992.Credit: Paul Chesley/NGC/Getty

Even here, serious internal problems surfaced. The British government refused to contribute because of the 1956 Suez crisis, when it came to blows with Egypt over control of the eponymous canal. However, many British Egyptologists and archaeologists, such as Mortimer Wheeler, lent support. UNESCO, preoccupied with rescuing known sites scheduled for flooding, did little to promote new archaeological investigation; instead, the work was independently financed by some 40 expeditions, and poorly coordinated as a result. Meanwhile, Nubians living in flooded areas were moved far from their ancestral homes, traditional means of subsistence and ways of life.

In the years that followed, UNESCO’s heritage work was repeatedly weakened by political pressures from member nations, a focus on monumental recovery rather than archaeological discovery, and a lack of participation by indigenous people. An example is Hampi in India — the remains of Vijayanagara, the capital of the last great Hindu kingdom — which was declared a World Heritage site in 1986. In 2011, the Indian government, backed by the Archaeological Survey of India, cleared modern infrastructure from the site, evicting residents and blocking UNESCO monitoring.

Meskell offers a trenchant critique of how UNESCO’s aim of preventing war sits oddly with projects commemorating sites associated with violence. In 1978, the Senegalese island of Gorée became a World Heritage site marking human exploitation in the international slave trade. In 1979, the former Nazi concentration camp at Auschwitz–Birkenau was listed. In 1996, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial — the only structure left standing after the atomic bombing of 1945 — was added. And in 2016, the medieval Armenian city of Ani in Turkey became a World Heritage site despite the 1915–22 Armenian genocide, which Turkey has denied. Now, Thailand is seeking UNESCO endorsement for the Burma–Siam Railway (known as the Death Railway); the country promotes it as a Second World War tourist attraction even though it was constructed by Japan using forced labour and prisoners of war.

Meskell notes that international recognition enshrines only one version of history. That, she argues, renders UNESCO complicit in recontextualizing “episodes of illegal occupation, atrocities, war crimes, and even genocide, while the victims are left to relive the trauma. This is the dark side of heritage branding.” Moreover, as tourism burgeons and the World Heritage brand has increased in value to member countries and listed sites, UNESCO’s overall budget of $250 million has been increasingly squeezed. It will probably fall further if the United States withdraws its membership for the second time, at the end of 2018. All this undermines the agency’s conservation and management of sites and its educational and scientific mission.

UNESCO’s workforce consists increasingly of volunteers. In 2017, some 600 unpaid interns from all over the globe thronged its headquarters, among consultants and a reduced staff trying to manage two or three posts per person. It is a sad decline from the aspirations of that post-war moment in 1945. And given the increasingly aggressive tone of international diplomacy, it is also worrying.

The wonder of the pyramids

The wonder of the pyramids

Q&A: Concrete conservator

Q&A: Concrete conservator

Ethics of exhibition

Ethics of exhibition

Golden boy

Golden boy