Losing a funding competition didn’t set Ellen Stofan back — instead, she did a career pivot, and came across new opportunities.Credit: NASA/Joel Kowsky

In 2021, planetary scientist Ellen Stofan was appointed undersecretary of science and research at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC, the US national research and museum complex. There, she oversees its scientific research centres as well as the National Air and Space Museum, the National Museum of Natural History and the National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. Before this, she was director of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, where she launched a 7-year restoration of the building and oversaw celebrations marking 50 years since the first Moon landing. Stofan’s doctoral research at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, focused on the geology of Venus.

Before joining the Smithsonian, she spent some 25 years working in space-related organizations — including NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and as the agency’s chief scientist. She helped to develop NASA’s plan to get humans to Mars and worked on the Magellan mission to Venus and the 13-year Cassini mission that documented Saturn and its moons.

Describe a typical day.

My portfolio is really broad, so there’s no typical day. I might be having a meeting about bringing pandas back to the zoo in Washington DC, or discussing how to dispose of the Smithsonian’s collection of human remains in an ethical way. Or talking about the budget — it’s always the budget.

Training: Persuasive grant writing

Is discussing the budget what you thought you would be doing at the start of your career?

Probably not, but the budget reflects the organization’s strategy and priorities, so you have to understand why you are putting money in certain areas. Speaking of priorities, over the past few years, I’ve been working on the Our Shared Future: Life on a Sustainable Planet research initiative, which we announced at the United Nations climate conference COP 27 two years ago. What’s amazing is the amount of science we were already doing along those lines. For example, in Montana, we have been recreating the ecosystem of an American prairie — we’ve reintroduced bison, and all of a sudden birds and insects have started coming back.

Did you plan to work in the museum sector?

I interned at the Air and Space Museum when I was an undergraduate, but at that time I just wanted to be a geologist, write papers and maybe work at a university. A thread through my career is working in great teams — that was why I enjoyed NASA so much. To explore Venus or the moons of Saturn, you have to put together an engaged team by bringing together people with different skills and ideas. At NASA, I led a team that was bidding for a Discovery Program grant, which can be used to fund smaller planetary missions using fewer resources and with shorter development times. Our proposed mission, the Titan Mare Explorer vessel, would explore the seas of liquid hydrocarbons, such as methane and ethane, on Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. Working with the fun, smart, creative and innovative people on the team did not feel like work at all. Our project was one of the three finalists in 2012, but another one was chosen.

How did that feel?

Not getting the grant was devastating — not just for me, but for the team. I felt like I had let them down. For a while, I couldn’t talk about the project without crying. I thought about leaving science, because I didn’t see how anything could ever match that.

It took me months to process it all. Before our bid, NASA had concluded that no research projects could reach the outer Solar System for less than a billion dollars. We were bidding for around US$400 million, and our proposal helped to pioneer the idea that, through innovation and judicious use of technology, these projects could be done more cheaply. Our mission created this small paradigm shift — and, all of a sudden, we saw people proposing projects that would go to the outer Solar System at much lower costs than before.

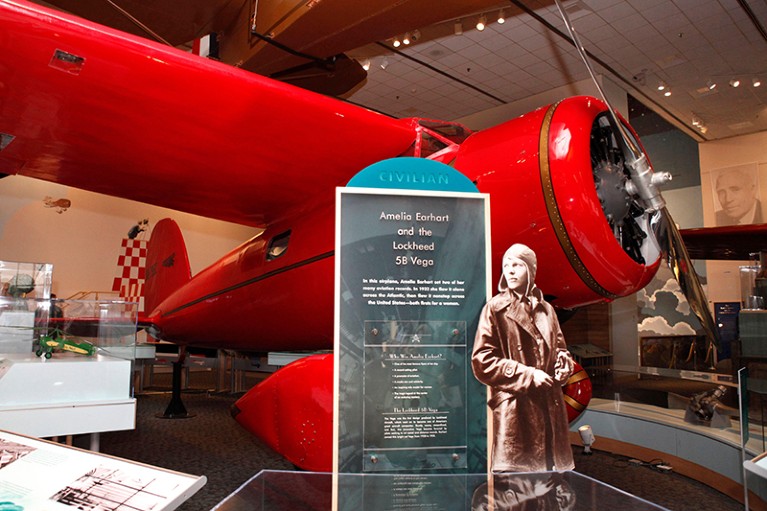

The display of Amelia Earhart’s plane at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.Credit: Jacquelyn Martin/AP Photo/Alamy

What is your approach to career setbacks?

You want to be the kind of person who shrugs off failure — but it’s hard. Everyone goes through it. When I was still processing losing the grant, I was invited to interview to be chief scientist of NASA. I got the job and held that position for three years. My career went a whole different way — I left NASA in 2016, and then the Smithsonian job came up.

Is the Titan Mare project still ongoing?

No, but I’m a co-investigator on a mission called Dragonfly. This drone will launch in late 2026 and will land on Titan in the 2030s. It’s going to fly around the equatorial region, where we think standing pools of liquid methane and liquid ethane might exist. There’s a lot of debate in the scientific community right now about whether life could ever exist on a body like Titan. What we will be able to learn about ‘prebiotic chemistry’ — the study of how chemical compounds assembled to form the precursors to life — from the mission is really exciting.

Did you always dream of a career in space exploration?

Not when I was younger, because my father was an engineer at NASA and the only people he worked with were men — so I just didn’t think it was a place for me. It was only by reading in National Geographic about primatologist and anthropologist Jane Goodall and palaeoanthropologist Mary Leakey, who studied human origins in Africa, that I realized that not only could women do science, but they could be famous scientists.

When I began my career in the 1980s, I was often either the only woman in the room, or one of the few. And some people thought that I didn’t belong in the room, because I was a woman. I had enough confidence to think, “What’s your problem?”

Things have changed a lot, but women are still under-represented in physics, engineering and computer science, and we’re not tapping into the talent. Hiring people from groups that are under-represented in science is not about achieving diversity for diversity’s sake. We know from scientific research that diverse teams perform better.

At NASA, I looked at our workforce and thought about whether we were tapping into the best talent. People often talk about diversity, but they forget about inclusion. NASA was sensitive to this after the Challenger accident — the space shuttle broke apart seconds after take off in 1986, killing all seven members of the crew. One of the findings was that managers were not listening to their teams. It’s important to create an environment in which everyone can contribute and participate. Even if you have a diverse workforce, if you don’t make people feel included, they’re not going to stay.

What is a key priority for you at the Smithsonian?

When we were redoing the museum, one important part of our mission was to inspire the next generation of innovators and explorers. Are we telling stories so that every kid who comes into the museum, no matter their race, gender or other aspect of their life, is going to find someone who looks like them?

In the past, the story of space centered charismatic figures, such as astronaut Neil Armstrong — but look at the success of the 2016 movie Hidden Figures, which is about a team of Black female mathematicians working for NASA during its early years. Visitors might notice that, at the museum, we’re telling a much broader range of stories. In February, the first private company, in partnership with NASA, touched down on the Moon; there are now many more countries involved in space exploration, and private individuals are going into space. The story of space is changing.

Do you have a favourite museum exhibit?

We have an X-wing fighter from the Star Wars films, which I absolutely love. We’ve also had the Starship Enterprise from the Star Trek series.

But my absolute favourite is aviator Amelia Earhart’s Lockheed Vega aeroplane. It’s this cheeky red colour that, to me, symbolizes her saying, ‘I’m going to fly despite what anyone thinks.’

Would you ever like to go into space?

When I went to my first launch, the rocket blew up. It was uncrewed, but it’s seared into my memory. I’m not terribly adventurous. I’m happy to be an armchair explorer.

Mother–daughter duo work together to find new worlds

Mother–daughter duo work together to find new worlds

Star-struck: living my childhood dream as an astronomer

Star-struck: living my childhood dream as an astronomer