Abstract

Extragenital malignant mixed mesodermal (müllerian) tumors (MMMT) are rare neoplasms, with but 24 well documented cases in the literature. Neuroendocrine differentiation in mixed müllerian neoplasms has been mentioned only anecdotally. We report on the clinical, pathological, and immunohistochemical features of a hitherto-undescribed extragenital MMMT with prominent neuroendocrine differentiation arising from the jejunal mesentery. This lesion was composed of a poorly differentiated epithelial component and a spindle cell component with heterologous (rhabdomyoblastic) differentiation. The bulk of the tumor consisted of small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, which exhibited strong immunoreactivity for NSE, LEU-7, chromogranin A and synaptophysin. Electronmicroscopy confirmed the presence of neurosecretory dense-core granules. The primary mesenteric origin of the tumor was established at autopsy. Along with a brief review of previously reported extragenital MMMT some histogenetic concepts relevant to this case are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Primary peritoneal neoplasms composed of both malignant epithelial and stromal elements have variously been referred to as extragenital malignant mixed mesodermal tumors (1, 2, 3, 4, 5), malignant mixed müllerian tumors (6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18), carcinosarcomas (19, 20, 21) and mixed tumors of müllerian type (22, 23, 24). This lack of consistent terminology reflects both the rarity of these lesions, mostly described in single case reports, as well as the uncertainties concerning the histogenesis. An extensive small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma component in a primary extragenital MMMT has never been documented before.

CASE REPORT

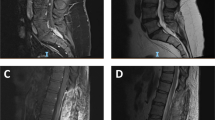

A 78-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital complaining of diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, anorexia and dyspnea and loose bowel movements. Abdominal examination revealed a large abdominal mass, corresponding to a subomental predominantly solid, partially cystic tumor on abdominal ultrasound and computerized tomograph. Chest X-ray was normal. This nulligravid patient recalled the removal of a benign endocervical polyp 45 years earlier; other than this there was no remarkable gynaecological history. Urgent laparatomy revealed and totally resected a bleeding abdominal tumor, measuring 16 cm in maximal dimension, attached to the jejunal mesentery and involving a mesenteric lymph node. The rest of the abdominal cavity, including ovaries, fallopian tubes and uterine corpus was normal. The postoperative course was unremarkable. No chemotherapy was started, in view of the overall poor medical condition of the patient. Approximately one month after surgery, ultrasound revealed multiple large (up to 10 cm) peritoneal nodules. The patient died shortly after admittance. Autopsy revealed the presence of innumerable peritoneal tumor nodules involving the visceral and parietal peritoneum. No primary tumor was found.

Pathologic Findings

Gross Appearance

The initial surgical specimen consisted of mesenteric tissue, diffusely invaded and markedly distorted by a soft, friable 16 × 13 × 8 cm tumor (Fig. 1). This tumor was predominantly solid, partially cystic. Firm, tan nodules were intermingled with areas of hemorrhage.

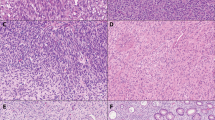

Light Microscopic Appearance

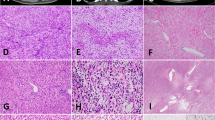

Light microscopy showed a tumor with a biphasic pattern. The larger part of the tumor consisted of sheets, cords and nests of poorly differentiated small to intermediate-sized cells with scant, ill-defined cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei (Fig. 2). Numerous perivascular pseudorosettes were present. Most nuclei displayed an evenly dispersed chromatin pattern, with inconspicous nucleoli. There was prominent nuclear molding, along with single-cell necrosis and a high mitotic rate. Scattered throughout this small cell component, trabeculae, sheets and glandular structures composed of larger cells with more prominent amphophilic cytoplasm, focally resembling endometroid adenocarcinoma, were present (Fig. 3). The sarcomatous areas consisted of spindle cells with oval or pleomorphic nuclei, focally arranged in bundles, mostly with a haphazardous architecture. Pleomorphic giant cells were conspicuous in some areas. Mitoses were plentiful, most of them atypical. The peritoneal nodules examined postmortem consisted mainly of the small cell component, with multinuclear giant cells scattered throughout. There was no evidence of endosalpingiosis or endometriosis. Multiple blocks from the ovaries, uterus and cervix were examined, none showed evidence of malignancy.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue utilizing the avidin-biotin complex method, with a panel of immunohistochemical markers comprising cytokeratin (1:50; Immunotech), desmin (1:10; Boehringer), chromogranin A (1:100; Argene-Biosoft), Leu-7 (1:10; Bectondickinson), myogenin (1:30, Novocastra), LCA (Leukocyte Common Antigen, 1:50), CD99 (MIC-2, 1:200), alpha smooth muscle actin (1:40), epithelial membrane antigen (1:100), BerEP4 (1:10), cytokeratin 7 (1:50), vimentin (1:40), synaptophysin (1:50), neuron specific enolase (1:200) (all antibodies from Dakopatts, Glostrup, Denmark, unless otherwise specified). It highlighted a previously unsuspected rhabdomyosarcomatous component, with sheets of small spindled and larger, tadpole-like cells staining for desmin and myogenin. The small cell component proved to be of an epithelial nature, with dot-like positivity of the tumor cells for EMA, keratin and BerEP4. Stains for LCA and CD99 were uniformly negative. There was strong and consistent expression of chromogranin A, synaptophysin, NSE and Leu-7. Much to our surprise, this neuroendocrine phenotype was maintained throughout a large part of the sarcomatous component (Fig. 4). The sarcomatous component strongly expressed vimentin, while no definite positivity for epithelial markers was noted. The abovementioned larger cyst-like spaces were lined by a conspicuous layer of BerEP4 negative, CK7 and vimentin positive flattened cells, with oval to spindle shaped nuclei.

Electron microscopic examination revealed some dense-core neurosecretory granules in all tumor components, confirming the neuroendocrine features suggested by immunohistochemistry.

DISCUSSION

The peritoneal surfaces are host to a range of benign and malignant lesions commonly encountered in the müllerian duct derivatives of the female genital tract (25). This remarkable müllerian potential of the peritoneal mesothelium and adjacent mesenchyme reiterates its shared mesodermal ancestry with the primary müllerian sytem, wich derives from invaginated coelomic epithelium. These lesions from the so-called “secondary müllerian system,” a term coined by Lauchlan in 1972 (26), are not restricted to the female peritoneum, since similar neoplasms have been described in men (27). Primary peritoneal müllerian tumors have been hypothesized to arise either from foci of endometriosis (8, 19), from müllerian duct remnants (21) or directly from the mesothelium and submesothelial mesenchyme, through a proces of metaplasia (23, 26, 28, 29).

Primary peritoneal malignant mixed mesodermal tumors (MMMT), similar to their more frequent counterparts in the uterus, fallopian tubes and cervix, are rare neoplasms. Not including MMMTs arising from the specialized ovarian surface epithelium (differing from the extraovarian peritoneal surface epithelium on a histochemical, enzymatic, biological and immunohistochemical level (30)), 24 examples of these tumors can be found in the literature, some of which could be questioned as to their primary peritoneal nature. In addition, 2 cases originating from the peritoneum were included in a large review on immunohistochemical properties of MMMTs, but were not amenable to proper analysis (24).

None of these tumors exhibited neuroendocrine differentiation, with the notable exception of a recent example arising in the cecal wall, where occasional epithelial cells stained for chromogranin (18). The neoplasm we report showed prominent neuroendocrine differentiation, including an extensive small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma component, with strong and consistent positivity for chromogranin A, synaptophysin, NSE and Leu-7. These findings could have been anticipated, in keeping with the Lauchlan theory, since, although sparsely mentioned, neuroendocrine differentiation has been recognized in uterine MMMTs (24, 31, 32, 33), as it has recently in an ovarian example (34). Some of these uterine MMMTs featured a small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma component, analogous to their infamous counterparts in the lung (32).

Extra-pulmonary small cell neuroendocrine carcinomas have been reported to occur in a variety of organs, such as the gastrointestinal system, paranasal sinuses, salivary glands, larynx, thymus, breast, prostate and genitourinary system (35, 36). Recently, a large single institutional series included one pelvic peritoneal example in a female patient (37). No detailed information regarding other possible primaries (especially female genital tract) or postmortem autopsy findings were available however.

Entities to be considered in the differential diagnosis in the present case include the intrabdominal desmoplastic small round cell tumor (DSRCT), a primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET) or a so-called small cell mesothelioma (38, 39, 40, 41, 42). These diagnoses are highly unlikely however, in view of the advanced age of the patient and the characteristic morphological and immunohistochemical features of this tumor.

Over the last decade, evidence from molecular genetic studies has accumulated towards a histogenetical epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation mechanism of histogenesis for MMMT (43, 44, 45, 46). This “conversion hypothesis” implies a common stem cell precursor with two phenotypically different tumor cell populations diverging at a rather late stage in clonal evolution (43). These data complement initial clinical, histological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies (44, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51), leading to the current view that these tumors should be regarded as “sarcomatoid” or “metaplastic” carcinomas, and treated accordingly (52).

A multipotent progenitor cell residing in the mesothelium or adjacent mesenchyme has been implicated in the histogenesis of both desmoplastic small round cell tumors (DSRCT) and mesotheliomas (38, 53, 54). Both of these neoplasms have been shown to coexpress keratin, vimentin, desmin and, interestingly, sometimes even neural markers such as NSE, Leu 7, chromogranin and synaptophysin. The phenotypical diversity of extragenital MMMTs suggests a similar origin from progenitor cells within the mesothelium, with multidirectional differentiation (23).

In view of this “conversion hypothesis,” the actual number of primary peritoneal MMMT may be even less than reported. Several cases occurred either metachronously or synchronously with ovarian and/or uterine endometroid adenocarcinoma or serous papillary carcinoma (6, 7, 9, 11, 18, 19, 22). Metastasis with epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation seems an equally defendable explanation in these cases, being more likely than the co-occurrence of 2 independent malignant tumors.

The multiple cyst-like spaces present in the tumor, most of which were lined by flattened cells with the immunohistochemical properties of mesothelium, could be interpreted as multifocal differentiation of tumor cells towards a mesothelial-like phenotype. This phenomenon reiterates the bewildering interplay between peritoneal Mullerian-type epithelial neoplasms and the mesothelial progenitor cells from which they seem to originate.

In summary, we report on a primary mesenteric neoplasm, exhibiting both carcinomatous and sarcomatous features, with a small cell carcinoma component and prominent neuroendocrine differentiation. The latter feature, suggesting a monoclonal origin in being expressed by all tumor components, lends further support to the “conversion hypothesis” regarding the histogenesis of MMMT.

References

Nguyen GK, Berendt RC . Aspiration biopsy cytology of metastatic endometrial stromal sarcoma and extragenital mixed mesodermal tumor. Diagn Cytopathol 1986; 2: 256–260.

Ohno S, Kuwano H, Mori M, Sakata H, Mori A, Shinohara K . Malignant mixed mesodermal tumor of the peritoneum with a complete response to cyclophosphamide. Eur J Surg Oncol 1989; 15: 287–291.

Solis OG, Bui HX, Malfetano JH, Ross JS . Extragenital primary mixed malignant mesodermal tumor. Gynecol Oncol 1991; 43: 182–185.

el-Jabbour JN, Helm CW, McLaren KM, Smart GE, Aitken J . Synchronous colonic adenocarcinoma and extragenital malignant mixed mesodermal tumor. Scott Med J 1989; 34: 567–568.

Deligdisch L, Plaxe S, Cohen CJ . Extrauterine pelvic malignant mixed mesodermal tumors. A study of 10 cases with immunohistochemistry. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1988; 7: 361–372.

Chen KKTK, Wolk RW . Extragenital malignant mixed müllerian tumor. Gynecol Oncol 1988; 30: 422–426.

Rose PG, Rodriguez M, Abdul-Karim FW . Malignant mixed müllerian tumor of the female peritoneum: treatment and outcome of three cases. Gynecol Oncol 1997; 65: 523–525.

Chumas JC, Thanning L, Mann WJ . Malignant mixed müllerian tumor arising in extragenital endometriosis: report of a case and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol 1986; 23: 227–233.

Garamvoelgyi E, Guillou L, Gebhard S, Salmeron M, Seematter RJ, Hadji MH . Primary malignant mixed müllerian tumor (metaplastic carcinoma) of the female peritoneum. A clinical, pathologic and immunohistochemical study of three cases and a review of the literature. Cancer 1994; 74: 854–863.

Garde JR, Jones MA, McAfee R, Tarraza HM . Extragenital malignant mixed müllerian tumor: review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol 1991; 43: 186–190.

Hasiuk AS, Petersen RO, Hanjani P, Griffin TD . Extragenital malignant mixed müllerian tumor: case report and review of the literature. Am J Clin Pathol 1984; 81: 102–105.

Nimaroff N, Gal D, Susin M, Lovecchio J . Extragenital malignant mixed müllerian tumor. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 1993; 14: 23–27.

Nishida T, Obuchi T, Sasaki T, Nagasue N, Yakushiji M . Extragenital malignant mixed müllerian tumor: a case report. Kurume Med J 1988; 35: 201–205.

Illert B, Sailer M, Gassel AM, Thiede A . [Primary extragenital manifestation of a malignant mixed Mullerian tumor of the major omentum.] Chirurg 1996; 67: 1273–1275.

Choong SYM, Scurry JP, Planner RS, Grant PT . Extrauterine malignant mixed müllerian tumor of primary peritoneal origin. Pathology 1994; 26: 497–498.

Marchevsky A, Jacobs AJ, Deppe G, Cohen CJ . Extragenital homologous mixed müllerian tumor. J Reprod Med 1982; 27: 110–112.

Ober WB, Black MB . Neoplasms of the subcoelomic mesenchyme: report of two cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1955; 59: 698–705.

Mira JL, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Husseinzadeh N . Malignant mixed müllerian tumor of the extraovarian secondary müllerian system. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1995; 119: 1044–1049.

Campins M, Madrenas J, Biosca M, Salas A, Tallada N, Garcia-Bragado F . Extra-uterine müllerian carcinosarcoma. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1986; 65: 811–812.

Westra WH, Anderson BO, Klimstra DS . Carcinosarcoma of the spleen. An extragenital malignant mixed müllerian tumor? Am J Surg Pathol 1994; 18: 309–315.

Ferrie RK, Ross RC . Retroperitoneal müllerian carcinosarcoma. Can Med Assoc J 1967; 97: 1290–1292.

Herman CW, Tessler AN . Extragenital mixed heterologous tumor of müllerian type arising in retroperitoneum. Urology 1982; 22: 49–50.

Weisz-Carrington P, Bigelow B, Schinella RA . Extragenital mixed heterologous tumor of müllerian type arising in the cecal peritoneum; report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum 1977; 20: 329–333.

George E, Manivel JC, Dehner LP, Wick MR . Malignant mixed müllerian tumors: an immunohistochemical study of 47 cases, with histogenetic considerations and clinical correlation. Hum Pathol 1992; 22: 215–223.

Fox H . Primary neoplasia of the female peritoneum. Histopathology 1993; 23: 103–110.

Lauchlan SC . The secondary müllerian system. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1972; 27: 133–146.

Shah IA, Jayram L, Gani OS, Fox IS, Stanley TM . Papillary serous carcinoma of the peritoneum in a man: a case report. Cancer 1998; 82: 860–866.

Nakayama K, Masuzawa H, Li SF, Yoshikawa F, Toki T, Nikaido T, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of the peritoneum adjacent to endometriotic lesions using antibodies for Ber-EP4 antigen, estrogen receptors, and progesterone receptors: implication of peritoneal metaplasia in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1994; 13: 348–358.

Mai KT, Yazdi HM, Perkins DG, Parks W . Pathogenetic role of the stromal cells in endometriosis and adenomyosis. Histopathology 1997; 30: 430–442.

Clement PB . Histology of the ovary. Am J Surg Pathol 1987; 11: 277–303.

Huntsman DG, Clement PB, Gilks CB, Scully RE . Small-cell carcinoma of the endometrium. A clinicopathological study of sixteen cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1994; 18: 364–375.

Manivel CM, Wick MR, Sibley RK . Neuroendocrine differentiation in müllerian neoplasms. An immunohistochemical study of a “pure” endometrial small-cell carcinoma and a mixed müllerian tumor containing small-cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol 1986; 86: 438–443.

Van Hoeven KH, Hudock JA, Woodruff JM, Suhrland MJ . Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the endometrium. Int J Gynecol Oncol 1995; 14: 21–29.

Lim SC, Kim DC, Suh CH, Kee KH, Choi SJ . Malignant mixed müllerian tumor (homologous type) of the adnexa with neuroendocrine differentiation: a case report. J Korean Med Sci 1998; 13: 207–210.

Richardson RL, Weiland LH . Undifferentiated small cell carcinomas in extrapulmonary sites. Semin Oncol 1982; 9: 484–496.

Barnardo DE, Stavrou M, Bourne R, Bogomoletz W . Primary carcinoid tumor of the mesentery. Hum Pathol 1984; 15: 796–798.

Galanis E, Frytak S, Lloyd RV . Extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma. Cancer 1997; 79: 1729–1736.

Ordóñez NG . Desmoplastic small round cell tumor. I: A histopathologic study of 39 cases with emphasis on unusual histological patterns. Am J Surg Pathol 1998; 22: 1303–1313.

Ordóñez NG . Desmoplastic small round cell tumor. II: An ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study with emphasis on new immunohistochemical markers. Am J Surg Pathol 1998; 22: 1314–1327.

Meis-Kindblom JM, Stenman G, Kindblom LG . Differential diagnosis of small round cell tumors. Semin Diagn Pathol 1996; 13: 214–241.

Fraggetta F, Magro G, Vasquez E . Primitive neuroectodermal tumour of the uterus with focal cartilaginous differentiation. Histopathology 1997; 30: 483–485.

Mayall FG, Gibbs AR . The histology and immunohistochemistry of small cell mesothelioma. Histopathology 1992; 20: 47–51.

Abeln ECA, Smit VTHBM, Wessels JW, De Leeuw WJF, Cornelisse CJ, Fleuren GJ . Molecular genetic evidence for the conversion hypothesis of the origin of malignant mixed müllerian tumours. J Pathol 1997; 183: 424–431.

Guarino M, Giordano F, Pallotti F, Polizzotti G, Tricomi P, Cristofori E . Malignant mixed müllerian tumor of the uterus. Features favoring its origin from a common cell clone and an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation mechanism of histogenesis. Tumori 1998; 84: 391–397.

Kounelis S, Jones MW, Papadaki H, Bakker A, Swalsky P, Finkelstein SD . Carcinosarcomas (malignant mixed müllerian tumors) of the female genital tract: comparative molecular analysis of epithelial and mesenchymal components. Hum Pathol 1998; 29: 82–87.

Masuda A, Takeda A, Fukami H, Yamada C, Matsuyama M . Characteristics of cell lines established from a mixed mesodermal tumor of the human ovary: carcinomatous cells are changeable to sarcomatous cells. Cancer 1987; 60: 2696–2703.

Costa MJ, Khan R, Judd R . Carcinosarcoma (malignant mixed müllerian [mesodermal] tumor) of the uterus and ovary. Correlation of clinical, pathologic, and immunohistochemical features in 29 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1991; 115: 583–590.

Silverberg SG, Major FJ, Blessing JA, Fetter B, Askin FB, Liao SY, et al. Carcinosarcoma (malignant mixed mesodermal tumor) of the uterus: a gynecologic oncology group pathologic study of 203 cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol 1990; 9: 1–19.

De Brito PA, Silverberg SG, Orenstein JM . Carcinosarcoma (malignant mixed müllerian (mesodermal tumor) of the female genital tract: immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis of 28 cases. Hum Pathol 1993; 24: 132–142.

Meis JM, Lawrence WD . The immunohistochemical profile of malignant mixed müllerian tumor: overlap with endometrial adenocarcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol 1990; 94: 1–7.

Sreenan JJ, Hart WR . Carcinosarcomas of the female genital tract. A pathologic study of 29 metastatic tumors: further evidence for the dominant role of the epithelial component and the conversion theory of histogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol 1995; 19: 666–674.

Colombi RP . Sarcomatoid carcinomas of the female genital tract (malignant mixed müllerian tumors). Semin Diagn Pathol 1993; 10: 169–175.

Hurlimann J . Desmin and neural marker expression in mesothelial cells and mesotheliomas. Hum Pathol 1994; 25: 753–757.

Parkash V, Gerald WL, Parma A, Miettinen M, Rosai J . Desmoplastic small round cell tumor of the pleura. Am J Surg Pathol 1995; 19: 659–665.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cokelaere, K., Michielsen, P., De Vos, R. et al. Primary Mesenteric Malignant Mixed Mesodermal (Müllerian) Tumor with Neuroendocrine Differentiation. Mod Pathol 14, 515–520 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880340

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3880340