Abstract

A clinicopathologic study of 108 cases of high-grade urothelial carcinomas of the renal pelvis is presented. Of the 108 tumors, 44 (40%) showed unusual morphologic features, including micropapillary areas (four cases), lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (two cases), sarcomatoid carcinoma (eight cases, including pseudoangiosarcomatous type), squamous differentiation and squamous cell carcinoma (15 cases), clear cells (two cases), glandular differentiation (two cases), rhabdoid, signet-ring or plasmacytoid cells (four cases), pseudosarcomatous stromal changes (four cases) and intratubular extension into the renal pelvis (three cases). Pathological staging was available in 62 patients; of these, 46 cases (74%) were in high stage (pT2–pT4) and 16 (26%) were in low stage (pTis, pTa, pT1). Clinical follow-up ranging from 1 to 256 months (median: 50 months) was available in 42 patients; of these, 26 (61%) died of tumor with a median survival of 31 months. The patients who did not die of their tumors showed only minimal or focal infiltration of the renal parenchyma by urothelial carcinoma, whereas those who died of their tumors showed massive infiltration of the kidney by the tumor. High-grade urothelial carcinomas of the renal pelvis can show a broad spectrum of histologic features similar to those seen in the urinary bladder. Our results support the finding that, unlike urothelial carcinomas of the bladder, the majority of primary urothelial carcinomas of the renal pelvis are of high histologic grade and present in advanced stages. Our study further highlights the fact that, in the renal pelvis, urothelial carcinomas show a tendency to frequently display unusual morphologic features and metaplastic phenomena. The importance of recognizing these morphologic variants of urothelial carcinoma in the renal pelvis is to avoid confusion with other conditions. The possibility of a high-grade urothelial carcinoma should always be considered in the evaluation of a tumor displaying unusual morphologic features in the renal pelvis, and attention to proper sampling as well as the use of immunohistochemical stains will be of importance to arrive at the correct diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Primary neoplasms of the renal pelvis are rare and account for approximately 7% of all renal tumors;1 the majority of them are of transitional cell type. Urothelium can display a wide range of metaplastic changes, and neoplasms arising from this epithelium can show several types of differentiation, especially in high-grade neoplasms. These changes have been described in detail in the urinary bladder,2, 3, 4 but have not been thoroughly analyzed in the renal pelvis. Their location within the kidney and the unusual morphologic appearances of these tumors may pose a challenge for histopathologic diagnosis.

The purpose of this study is to report the clinicopathologic features in a series of high-grade urothelial carcinomas of the renal pelvis with emphasis on unusual morphologic variants of these tumors.

Materials and methods

All cases of total nephrectomy specimens coded as carcinoma of the renal pelvis were retrieved from the surgical pathology files at the Ohio State University Medical Center between the years 1970 and 2000, and from the University Hospital in Plzen, the Czech Republic between 1995 and 2001. Demographic features analyzed included age, sex, tumor location and clinical stage. A total of 157 patients were identified. Of the 157 cases, 108 (69%) were classified as high-grade neoplasms according to the WHO/ISUP consensus.5 From six to 14 glass slides stained with hematoxylin & eosin were retrieved for each case. The histologic features analyzed included: growth pattern, histologic type, histologic grade, evidence of divergent differentiation, unusual stromal features and patterns of infiltration into the adjacent renal parenchyma. Pathological staging was established using the current American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC/TNM) system.6

A few of the patients included in this series are presented in more detail elsewhere.7 Selected tumors in which morphologic features could give rise to alternate diagnoses were stained with a panel of immunohistochemical markers and with histochemical stains including the periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) reaction and Alcian blue. DNA-in situ hybridization for Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) (EBER) was performed in the two cases of lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (LELC). For immunohistochemical analysis, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were cut at 4 μm, dried for 1 h at 60°C, deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through graded alcohols. Antigen retrieval was performed using Target Retrieval Solution, 10 × concentrate (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA, USA) for all the antibodies tested, except for actin. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by immersion in absolute methanol containing 3% (vol/vol) hydrogen peroxide for 5 min. Immunohistochemical stains were performed with commercially available antibodies utilizing a standard avidin–biotin complex immunoperoxidase technique in a Dako Autostainer (Dako). Tissue sections were incubated with antibodies to cytokeratin AE1/AE3 (DakoCytomation; 1:1000), CK7 (DakoCytomation; 1:200), CK20 (DakoCytomation; 1:200), polyclonal CEA (DakoCytomation; 1:1000), vimentin (DakoCytomation; 1:200), EBV LMP (CS 1–4) (DakoCytomation; 1:200), EMA (DakoCytomation; 1:400) and CD10 (Novocastra, Newcastle, UK; 1:20). Positive and negative controls were run concurrently for all antibodies tested.

For EBER-1 and EBER-2 detection, RNA-in situ hybridization was performed on sections using fluorescein-tagged oligomers specific for EBER-1 and EBER-2, according to the manufacturer's recommendations (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA). This system employs nitroblue tetrazolium and bromochloroindoly phosphate as the chromogen and nuclear fast red as nuclear counterstain; thus, a positive signal was evident as a dark blue color against a light pink background.

Results

Clinical Features

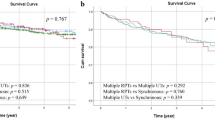

The ages of our patients ranged from 40 to 106 years with a median of 67 years. In all, 39 patients were women, and 62 patients were men; in seven cases, the patient's gender could not be established due to incomplete clinical information. In total, 44 tumors were located on the left side, 36 on the right side, one was bilateral and in 27 cases information regarding laterality was not available. Clinical staging information was not available in all patients because of the referral nature of many of the cases. Staging information was available in 62 patients with high-grade carcinoma: 16 patients were in low pathological stage (a-1) and 46 were in high pathological stage (2–4) (Table 1). Clinical follow-up ranging from 1 to 256 months (median 50 months) was available in 42 patients; 26 died with tumor with a median survival of 31 months; of these, 24 were in high stage and two were in low stage. Five patients died of unrelated causes and 11 patients were alive with no evidence of tumor (three with high stage and eight with low stage). The three patients with high-stage tumors who are alive showed only focal infiltration of the kidney by tumor. In contrast, patients in the same stage and grade who died of their tumors showed extensive invasion of the kidney by tumor. Seven patients also had a synchronous intraparenchymatous renal tumor, of which four were conventional clear cell renal cell carcinomas, one was a papillary renal cell carcinoma, and two were incidental metanephric adenomas.

Pathologic Features

The majority of the tumors (60%) showed the conventional features of high-grade urothelial carcinoma according to previously established criteria.5 In all, 44 cases in this study (40%) showed unusual morphologic features (Table 2).

High-grade urothelial carcinoma with conventional features (CHGUC)

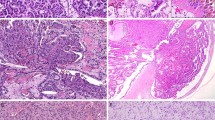

These tumors showed an abnormal architecture, in which the cells appeared predominantly or totally disorderly on scanning magnification, and showed a variable degree of nuclear atypia ranging from moderate to severe with pleomorphic features (Figure 1). The majority of the tumors were papillary, but solid and diffuse patterns were also recognized.

Micropapillary carcinoma

Micropapillary features characterized four tumors. Two types of micropapillary pattern were observed: invasive and noninvasive. Two patients showed a noninvasive pattern, one showed an invasive pattern, and another showed both invasive and noninvasive patterns. The percentage of micropapillary component in these tumors varied from 20 to 60%. The invasive pattern of micropapillary carcinoma consisted of small clusters of neoplastic epithelial cells with high nuclear grade that formed tight micropapillary structures surrounded by a clear retraction artifact. The noninvasive pattern was composed of delicate papillae with central fibrovascular cores. The papillae were lined by cells with high nuclear grade showing either scant or abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. All the tumors were CK7 positive, one was CK 20 positive, one was vimentin positive, and two were focally positive for CEA.

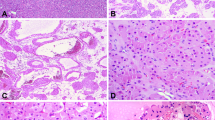

LELC

LELC was present in two patients: in one case the LELC component predominated and accounted for more than 80% of the tumor. In the second case, the LELC component was more limited, and the tumor showed extensive CHGUC with focal areas of LELC involving less than 20% of the lesion. The LELC pattern showed islands of cells with large, vesicular nuclei with prominent eosinophilic nucleoli, parachromatin clearing and numerous mitoses (Figure 2). The cytoplasm was amphophilic with ill-defined cell borders giving the tumor a syncytial appearance; the individual cells or groups of cells were surrounded focally by a lymphoid host response. Immunostains with cytokeratin AE1/AE3 was diffuse and strongly positive in the large atypical cells. LCA was negative in the neoplastic cells. EBV latent membrane protein detection by immunohistochemistry and analysis of EVB-EBER by DNA-in situ hybridization was negative in both tumors tested.

Sarcomatoid carcinoma

Six tumors displayed features of spindle cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis. The spindle cell carcinomas showed a proliferation of atypical spindle cells arranged in short interlacing fascicles or showing a vague storiform pattern. The nuclei showed coarsely clumped chromatin and prominent, often multiple nucleoli, and were surrounded by scant lightly eosinophilic cytoplasm. Areas of transition with conventional urothelial carcinoma could be identified in all cases. The spindle cell component accounted for 10–30% of the tumor in two, 30–60% of the tumor in three and >60% of the tumor in one. Immunohistochemical stains carried out in five cases showed positivity of the spindle tumor cells for cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and vimentin. One interesting finding was that the epithelioid high-grade areas in two of the tumors coexpressed vimentin, while the better-differentiated low-grade urothelial areas in the same tumors were negative for this marker. Areas displaying a prominent pseudoangiosarcomatous appearance characterized two of the spindle cell carcinomas. These tumors showed areas of CHGUC containing vessel-like spaces in the stroma lined by hyperchromatic, flat or cuboidal cells that seemed to be forming anastomosing vascular channels (Figure 3). Immunohistochemical stains showed that the cells lining the vessel-like spaces were CK7 positive and CD31 negative. Two tumors showing the features of sarcomatoid carcinoma were composed of a mixture of sarcomatous areas with intimately admixed, recognizable high-grade epithelial areas (Figure 4). The epithelial areas were positive for CK7, cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and EMA, and were negative for vimentin and actin. The sarcomatoid areas were positive for vimentin and actin, and negative for all epithelial markers. Both components were negative for CD31 and CEA.

Urothelial carcinoma with squamous differentiation

In all, 14 patients with CHGUC showed tumors with prominent areas of squamous differentiation characterized by sheets of cells with well-defined cell borders, deeply eosinophilic cytoplasm, focal keratin pearl formation and large nuclei with prominent nucleoli occupying more than 30% of the tumor. All these tumors showed areas of transition with urothelial carcinoma and had infiltrating borders with wide invasion of the renal parenchyma. One case showed a pure high-grade squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) associated with squamous metaplasia of the urothelium in the renal pelvis.

Clear cell change

Clear cell change was observed in four patients with high-grade urothelial carcinoma in this study. The clear cell changes involved 20–40% of the lesions; two cases were associated with focal squamous differentiation. Nests or sheets of cells characterized the clear cell areas with well-defined cell membranes circumscribing abundant optically clear cytoplasm (Figure 5). The clear cell areas merged imperceptibly with the conventional high-grade urothelial carcinomatous component.

Adenocarcinoma arising in TCC

Two patients showed tumors with well-developed glandular areas admixed with the urothelial elements. The adenocarcinomatous areas showed well-formed glands lined by atypical cells with large nuclei and moderate amount of cytoplasm filled with mucin. The surrounding urothelial component showed features of CHGUC.

Rhabdoid, plasmacytoid and signet-ring cells

Three tumors were characterized by CHGUC showing areas in which the cytoplasm of the tumor cells was abundant, with large paranuclear eosinophilic inclusions identical to those seen in the so-called ‘rhabdoid’ cells (Figure 6a). These cells frequently adopted a nested or alveolar appearance and showed transitions with the areas of high-grade urothelial carcinoma. Cytokeratin AE1/AE3 showed strong positivity within the paranuclear eosinophilic inclusions. In two cases, in addition to the rhabdoid cells, there were also cells with prominent signet-ring cell features characterized by cytoplasmic vacuoles with displacement of the nuclei towards the periphery (Figure 6b). In one tumor, the cells showed a multivacuolated, lipoblast-like appearance. Special stains, including PAS and Alcian blue showed PAS-positive intracytoplasmic vacuoles that were negative for Alcian blue. In one patient, the tumor cells showed a striking ‘plasmacytoid’ appearance, with round, eccentric nuclei surrounded by an ample rim of abundant, deeply eosinophilic cytoplasm reminiscent of plasma cells (Figure 6c). ‘Rhabdoid’ inclusions were not noted in these cells.

CHGUC with pseudosarcomatous stroma

Four patients presented with tumors showing a prominent pseudosarcomatous myofibroblastic reaction in the stroma surrounding the invasive areas of urothelial carcinoma (Figure 7). The reactive spindle cells in the stroma showed enlarged nuclei surrounded by abundant cytoplasm, with focal vacuolization of the nuclei. The background varied from edematous or myxoid to collagenous with sclerosing features. No mitotic figures could be identified in the stromal component. Immunohistochemical stains showed that the spindle stromal cells were positive only for vimentin and negative for cytokeratins.

CHGUC with spread into the renal pelvis

Most tumors in the present series had a pushing or infiltrative border, but in three patients, an unusual form of intratubular spread was present. In these tumors, the neoplastic transitional epithelium lined, and in some cases filled, the lumen of the minor calyces and collecting tubules (Figure 8). In one case, replacement of the normal epithelium by dysplastic urothelium in a Pagetoid pattern was seen. The neoplastic cells were confined to the tubules without infiltration into the surrounding renal parenchyma, similar to the process of cancerization of ducts or lobules sometimes observed in the breast of patients with mammary carcinoma.

Discussion

Urothelial carcinomas of the renal pelvis are relatively rare tumors that account for approximately 7% of all renal neoplasms.1 Interestingly, the majority of urothelial carcinomas arising from the renal pelvis are high-grade tumors. We have analyzed a series of primary high-grade urothelial carcinomas of the renal pelvis. These tumors accounted for 69% of all urothelial carcinomas of the renal pelvis in our material. In a recent study by Olgac et al,8 71% of all urothelial carcinomas of the renal pelvis were high grade. Another recent study also showed that 89% of urothelial carcinomas of the renal pelvis were either grade 2/3 or 3/3.9 Urothelial carcinomas of the renal pelvis also more often appear to be in higher stages than their urinary bladder counterpart. In the study by Olgac et al, 45% of the tumors presented in high pathological stages, compared with bladder tumors, of which only 25% were in high stages.8 In the present series, staging information was available in 62 patients with high-grade carcinomas and 74% of our cases (46/62 cases) were high stage.

Morphologic variation due to aberrant differentiation is a well-recognized phenomenon in urothelial carcinoma of the bladder.2 The most commonly reported events are squamous and glandular differentiation, which may be focal or widely distributed.4 The same phenomenon may involve other sites along the urogenital tract. In the renal pelvis, unusual variants of urothelial carcinoma displaying divergent differentiation have also been rarely described.2, 3 The majority of the tumors in our study (60%) showed the usual features of high-grade transitional cell carcinoma. However, 40% of the cases in this series were characterized by unusual morphologic features, including a micropapillary component, undifferentiated (lymphoepithelioma-like) areas, spindle cell (sarcomatoid) morphology, squamous differentiation and glandular differentiation with mucus-producing cells. In addition, tumors with clear cells, signet-ring cells, rhabdoid cells and plasmacytoid cells were also seen. A reactive spindle cell pseudosarcomatous stroma was also present in some cases, as well as an unusual form of spread into renal tubules. The occurrence of these unusual morphologic features may contribute to difficulties in the histopathologic diagnosis of these lesions.

The micropapillary variant of urothelial carcinoma is a very rare form of urothelial carcinoma that has been reported in the urinary bladder,10 ureter7, 11 and renal pelvis.7, 12 Two different patterns have been described in the urinary tract, the invasive micropapillary pattern composed of tight clusters of neoplastic atypical cells that form small micropapillary structures surrounded by clear retraction spaces and the noninvasive pattern composed of slender finger-like projections with or without fibrovascular cores.10 The main differential diagnosis for these tumors is with metastasis of papillary carcinoma from other organs or with the papillary variant of renal cell carcinoma; thorough sampling with identification of areas showing the more classical features of urothelial carcinoma may be helpful for establishing a definitive diagnosis.

‘Lymphoepithelioma’ is the old term used to designate a poorly differentiated malignant epithelial tumor of the nasopharynx related in most cases to EBV. LELC has been reported in other organs such as salivary glands,13 lung,14 thymus,15 cervix,16 skin,17 stomach18 urinary bladder19, 20 and renal pelvis.21, 22 In the single case reported of LELC of the renal pelvis studied for EBV by in situ hybridization,22 the Epstein–Barr viral genome was negative. In the present study, both the anti-EBV LMP antibody as well as the EVB-EBER by DNA-in situ hybridization was also negative in both tumors tested. The main differential diagnosis for these tumors is with high-grade lymphoma; immunoreactivity for cytokeratin in the atypical cell component will help establish the correct diagnosis.

Eight tumors in our series were classified as sarcomatoid carcinoma of the renal pelvis. This tumor has been previously well recognized in the renal pelvis.23, 24, 25 All of the tumors in the present series had recognizable areas of high-grade TCC in addition to the sarcomatoid areas. Sarcomatoid urothelial carcinoma of the urinary tract has been reported in advanced stages at the time of diagnosis and is associated with a poor prognosis.24, 25 Clinical follow-up was available only in two cases in our study: one patient died 3 months after diagnosis with metastasis from a pT3 tumor, and the other patient who had a pT2 tumor was alive and free of disease 108 months after diagnosis. The differential diagnosis for these lesions includes a variety of spindle cell sarcomas and secondary infiltration of the renal pelvis by sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma. Identification of better-differentiated areas of urothelial carcinoma as well as demonstration of transitions with in situ urothelial carcinoma can help in the differential diagnosis. Immunohistochemical studies are of limited value, since there can be much overlap between sarcomatoid carcinoma of the renal pelvis and sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma in their reactivity for the different markers available.

SCCs have been reported in the renal pelvis and account for 10% of cases in some series.26 They are usually associated with calculi, chronic infection and squamous metaplasia of the neighboring epithelium.27, 28 The majority are keratinizing tumors that show high nuclear grade and have an unfavorable prognosis, but there are reported cases of verrucous carcinoma associated with urolithiasis that have a better clinical outcome.29 Only one patient in our study corresponded to a pure SCC, with focal areas of squamous metaplasia of transitional epithelium. In all, 14 patients in our series, however, had high-grade urothelial carcinomas showing prominent areas of squamous differentiation, two of them displaying focal clear cell changes. These tumors showed infiltrating borders with extensive invasion of the renal parenchyma and they were in pathological stage T3, except for one case that was T2 and another one that was T4.

Clear cell appearance has been reported as an infrequent change in urothelial tumors.30 In the present series, this phenomenon was observed involving wide areas of the tumor in four high-grade urothelial carcinoma, two in association with areas of squamous or glandular differentiation. In the urinary bladder, the differential diagnosis for these tumors is with adenocarcinomas of Mullerian origin, or metastases from a clear cell renal cell carcinoma.31 In the renal pelvis, the main differential diagnosis is with secondary invasion by a clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Some cases can be problematic, especially in high-grade tumors with pleomorphism and mitoses that show extensive clear cell changes. Identification of areas displaying features of conventional transitional cell carcinoma will be of help for arriving at the correct diagnosis. Immunohistochemical stains can also be of aid in distinguishing clear cell renal cell carcinoma from high-grade urothelial carcinoma with clear cell features. Urothelial carcinomas are negative for the renal cell carcinoma antigen and positive for CK7 and CK20, while renal cell carcinoma is generally negative for CK20 and positive for RCC antigen.32, 33

Tumors with areas showing the features of ‘rhabdoid’ tumors have been described in high-grade urothelial carcinoma.34 Microscopically, the cells show abundant cytoplasm with paranuclear eosinophilic inclusions corresponding to whorls of intermediate filaments as seen by electron microscopy. In the cases reported in the literature, the patients had a rapidly progressive clinical course. The only patient in our study showing this feature for which we had clinical follow-up also followed a rapidly fatal course. The differential diagnosis for these lesions is with rhabdoid tumors of the kidney; however, this tumor is generally a childhood neoplasm that only rarely occurs in adults. Another condition that may enter in the differential diagnosis is renal cell carcinoma. Renal cell carcinoma can also display a rhabdoid phenotype, usually in association with areas of conventional clear cell renal cell carcinoma.35 The differential diagnosis can be clarified by demonstrating transitions with areas of better differentiated RCC, or by finding foci of in situ urothelial carcinoma with dysplasia of the urothelium.

Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma is a rare variant of urothelial neoplasm described in the urinary bladder in association with high-grade tumors.36 One of the cases reported in the bladder had bone metastasis and was confused with a plasmacytoma.37 Immunohistochemical stains may be of aid in such instances for distinguishing these tumors from lymphomas and other lymphoproliferative conditions by demonstrating light chain restriction and absence of markers of maturation of B-lymphocytes such as CD20. It is interesting to note in this context that none of the patients in our series showed features of small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma has been reported in the urinary bladder as an uncommon tumor that affects predominantly older patients and is associated with a poor prognosis and several large series have been reported in the literature.38, 39 However, only a few case reports have been published on this type of tumor arising in the renal pelvis.40, 41, 42 The reason for this discrepancy is not apparent.

A peculiar pattern of intratubular infiltration of the renal papilla was seen in three cases. In these cases, the transitional neoplastic epithelium lined the minor calyces and replaced the normal epithelium. In one patient, the infiltration of the tubules displayed a pagetoid appearance. The gross appearance of this type of extension into the tubules can be quite deceptive and in some cases can mimic amyloid kidney.43 This form of infiltration can be confused with primary carcinoma of the kidney such as carcinoma with tubular differentiation, ductal cell carcinoma or loopomas.44 Another differential diagnosis for these tumors is the nested variant of urothelial carcinoma described in the bladder by Murphy and Deana.45 This variant is characterized by neoplastic cells arranged in small nests and within small tubular lumina; the recognition of normal collecting tubules filled with cells and the presence of urothelial carcinoma in the renal pelvis are the most useful signs to rule out this lesion.

Pseudosarcomatous myofibroblastic reaction is a change that can be seen in urothelial carcinoma, although it is more commonly seen as a sequel to inflammatory processes or postoperatively following endoscopic procedures.46 When associated with cancer, even the metastases from urothelial carcinoma can display this pseudosarcomatous reaction.47 The histological features include an edematous or myxoid background with spindle cells showing large nuclei, often prominent nucleoli and scant normal-appearing mitotic figures, but no cytologic atypia. The differential diagnosis is with sarcomatoid carcinoma. Some tumors in our series with pseudosarcomatous stroma showed apparent transitions between the epithelial nests and the spindle cells; however, despite some nuclear enlargement, the chromatin was not coarse and stains for epithelial markers were negative in the stromal component.

In summary, high-grade urothelial carcinomas of the renal pelvis can have a broad spectrum of histologic features similar to those seen in the urinary bladder. Our results support the findings of Olgac et al8 that, unlike urothelial carcinomas of the bladder, the majority of primary urothelial carcinomas of the renal pelvis are of high histologic grade and present in advanced stages. Our study also showed that the extent of infiltration into the adjacent renal parenchyma by high-grade urothelial carcinoma of the renal pelvis appears to show a direct correlation with clinical outcome; study of additional patients may help confirm this observation. This study additionally highlights the fact that, in the renal pelvis, urothelial carcinomas have a tendency to frequently display unusual morphologic features and metaplastic phenomena. The importance of recognizing these morphologic variants of urothelial carcinomas in the renal pelvis is to avoid confusion with other conditions. The possibility of a high-grade urothelial carcinoma should always be considered in the evaluation of a tumor displaying unusual morphologic features in the renal pelvis, and attention to proper sampling as well as the use of immunohistochemical stains will be of importance to arrive at the correct diagnosis.

References

Droller MJ . Transitional Cell Carcinoma: upper tracts and bladder. In: Walsh PC, Gittes RF, Perlmutter AD, Stamey TA (eds). Campbelĺs Urology. WB Saunders: Philadelphia, 1986, pp 1343–1440.

Murphy WM, Beckwith JB, Farrow GM . Tumors of the Kidney, Bladder and Related Structures. Atlas of Tumor Pathology, 3rd edn. AFIP: Washington DC, 1993, pp 313–321.

Eble JN, Young RH . Carcinoma of the urinary bladder: a review of its diverse morphology. Semin Diagn Pathol 1997;14:98–108.

Bostwick SM, Eble JN . Renal pelvis and ureter. In: Bostwick DM, Eble JN (eds). Urologic Surgical Pathology. Mosby: St Louis, MO, 1997, pp 149–165.

Epstein JI, Amin MB, Reuter VR, et al. The World Health Organization/International Society of Urological Pathology consensus classification of urothelial (transitional cell) neoplasms of the urinary bladder. Bladder Consensus Conference Committee. Am J Surg Pathol 1998;22:1435–1448.

AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (AJCC). Genitourinary sites: renal pelvis and ureter. In: Greene GL, Page DL, Fleming ID et al (eds). AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Springer Verlag: New York, 2002, pp 329–330.

Perez-Montiel D, Hes O, Michal M, et al. Micropapillary carcinoma of the upper urogenital tract. Clinicopathologic study of 5 cases. Am J Clin Pathol (in press).

Olgac S, Mazumdar M, Daldagni G, et al. Urothelial carcinoma of the renal pelvis. A clinicopathologic study of 130 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;12:1545–1552.

Stewart GD, Barisol SV, Grigor KM, et al. A comparison of the pathology of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder and upper urinary tract. BJU Int 2005;95:791–793.

Amin MB, Ro JY, el-Sharkawy T, et al. Micropapillary variant of transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Histologic pattern resembling ovarian papillary serous carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1994;18:1224–1232.

Oh YL, Kim KR . Micropapillary variant of transitional cell carcinoma of the ureter. Pathol Int 2000;50:52–56.

Ribe A, Sole M, Campo E, et al. Papillary transitional cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1996;20:125–126.

Saw D, Lau WH, Ho JH, et al. Malignant lymphoepithelial lesion of the salivary glands. Hum Pathol 1986;17:914–923.

Butler AE, Colby TV, Weiss LM . Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the lung. Am J Surg Pathol 1989;13:629–632.

Ritter JH, Wick MR . Primary carcinoma of the thymus gland. Semin Diagn Pathol 1999;16:18–31.

Martorell MA, Julian JM, Calabuig C, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2002;126:1501–1505.

Leung EY, Yik YH, Chan JK . Lack of demonstrable EBV in Asian lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of skin. Am J Surg Pathol 1995;19:974–976.

Wang HH, Wu MS, Shun CT, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the stomach: a subset of gastric carcinoma with distinct clinicopathological features and high prevalence of Epstein–Barr virus infection. Hepatogastroenterology 1999;46:1214–1219.

Holmang S, Borghede G, Johansson SL . Bladder carcinoma lymphoepithelioma-like differentiation: a report of 9 cases. J Urol 1998;159:779–782.

Amin MB, Ro JY, Lee KM, et al. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Am J Surg Pathol 1994;18:466–473.

Cohen RJ, Stanley JC, Dawkins HJ . Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the renal pelvis. Pathology 1999;31:434–435.

Fukunaga M, Ushigome S . Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the renal pelvis: a case report with immunohistochemical analysis and in situ hybridization for the Epstein–Barr viral genome. Mod Pathol 1998;11:1252–1256.

Piscioli F, Bondi A, Scappini P, et al. True sarcomatoid carcinoma of the renal pelvis. Eur Urol 1984;10:350–355.

Suster S, Robinson MJ . Spindle cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study demonstrating coexpression of keratin and vimentin intermediate filaments. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1989;113:404–408.

Lopez-Beltran A, Escudero AL, Cavazzana AO, et al. Sarcomatoid transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis. A report of five cases with clinical, pathological, immunohistochemical and DNA ploidy analysis. Pathol Res Pract 1996;192:1218–1224.

Utz DC, McDonald JR . Squamous cell carcinoma of the kidney. J Urol 1957;78:540–552.

Blacher EJ, Johnson DE, Abdul-Karim FW . Squamous cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis. Urology 1985;25:124–125.

Raghavendran M, Rastogi A, Dubey D, et al. Stones associated renal pelvic malignancies. Indian J Cancer 2003;40:108–112.

Sheaff M, Fociani P, Badenoch D, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of the renal pelvis: case presentation and review of the literature. Virchows Arch 1996;428:375–379.

Kotliar SN, Wood CG, Schaeffer AJ, et al. Transitional cell carcinoma exhibiting clear features. A differential diagnosis for clear cell adenocarcinoma of the urinary tract. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1995;119:79–81.

Oliva E, Amin MB, Jimenez R, et al. Clear cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder: a report and comparison of four tumors of Mullerian origin and nine of probable urothelial origin with discussion of histogenesis and diagnostic problems. Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:190–197.

Skinnider BF, Folpe AL, Hennigar RA, et al. Distribution of cytokeratins and vimentin in adult renal neoplasms and normal renal tissue: potential utility of a cytokeratin antibody panel in the differential diagnosis of renal tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:747–754.

Chu P, Arber DA . Paraffin-section detection of CD10 in 505 nonhematopoietic neoplasms. Frequent expression in renal cell carcinoma and endometrial stromal sarcoma. Am J Clin Pathol 2000;113:374–382.

Kumar S, Kumar D, Cowan DF . Transitional cell carcinoma with rhabdoid features. Am J Surg Pathol 1992;16:515–521.

Gokden N, Nappi O, Swanson PE, et al. Renal cell carcinoma with rhabdoid features. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:1329–1338.

Zukerberg LR, Harris NL, Young RH . Carcinomas of the urinary bladder simulating malignant lymphoma. A report of five cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1991;15:569–576.

Sahin AA, Myhre M, Ro JY, et al. Plasmacytoid transitional cell carcinoma. Report of a case with initial presentation mimicking multiple myeloma. Acta Cytol 1991;35:277–280.

Cheng L, Pan CX, Yang XJ, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder: a clinicopathologic analysis of 64 patients. Cancer 2004;101:957–962.

Trias I, Algaba F, Condom E, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Presentation of 23 cases and review of 134 published cases. Eur Urol 2001;39:85–90.

Mazzuchelli L, Studer UE, Kraft R . Small-cell undifferentiated carcinoma of the renal pelvis 26 years after subdiaphragmatic irradiation for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Br J Urol 1995;76:403–404.

Guillou L, Duvoisin B, Chobaz C, et al. Combined small-cell and transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis. A light microscopic, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study of a case with literature review. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1993;117:239–243.

Essenfeld H, Manivel JC, Benedetto P, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis: a clinicopathological, morphological and immunohistochemical study of 2 cases. J Urol 1990;144:344–347.

Hes O, Michal M, Kinkor Z, et al. Renal cell carcinoma resembling amyloidosis on gross appearance. Report of five cases. Int J Surg Pathol 2002;10:41–45.

Fujimoto H, Tobisu K, Sakamoto M, et al. Intraductal tumor involvement and renal parenchymal invasion of transitional cell carcinoma in the renal pelvis. J Urol 1995;153:57–60.

Murphy WD, Deana DG . The nested variant of transitional cell carcinoma: a neoplasm resembling proliferation of Brunn's nests. Mod Pathol 1992;5:240–243.

Hughes DF, Biggart JD, Hayes D . Pseudosarcomatous lesions of the urinary bladder. Histopathology 1991;18:67–71.

Mahadevia PS, Alexander JE, Rojas-Corona R, et al. Pseudosarcomatous stromal reaction in primary and metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1989;13:782–790.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Perez-Montiel, D., Wakely, P., Hes, O. et al. High-grade urothelial carcinoma of the renal pelvis: clinicopathologic study of 108 cases with emphasis on unusual morphologic variants. Mod Pathol 19, 494–503 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800559

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800559

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Squamous cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis in a patient with long-term spinal cord injury—a case report

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2021)

-

A case report of primary upper urinary tract signet-ring cell carcinoma and literature review

BMC Urology (2020)

-

Clinicopathologic analysis of upper urinary tract carcinoma with variant histology

Virchows Archiv (2020)