Abstract

Surgical staging of endometrial carcinoma includes the collection of peritoneal washings in the abdomen and pelvis. A positive finding upstages patients to International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage IIIA. However, the prognostic significance of such an upstaging, and thus the justification for the routine performance of this procedure, is unclear. This 5-year retrospective study was conducted to determine the frequency and prognostic significance of upstaging of endometrial carcinoma based solely on positive washings. The cohort for the study was collected by review of pathology reports of all washings that were performed prior to hysterectomies for suspected endometrial carcinomas over a 5-year period (01/1995–12/1999). Cases with positive cytology were selected if there was no grossly apparent intraperitoneal disease, no histologic evidence of extra-uterine tumor and the cases would otherwise have been considered stage I or II (case group). An age-matched control group was selected of stage I and II patients with the same histologic subtypes and negative washings (n=19). Of 220 endometrial carcinomas, peritoneal washing cytology was abnormal in 19 (8.6%) and was solely responsible for upstaging only 10 patients (4.5% of all cases, eight—endometrioid, one–serous, one–mixed; nine stage IA or IB and one stage IIB). Adjuvant therapy was administered in 90% of the case group and 74% of the control group. After a median follow-up of 51 months (case group) and 63 months (control group), we found only a single patient with progression of disease (recurrence, metastases or death) in the control group. It is concluded that abnormal cytology without other evidence of extrauterine disease leads to upstaging of a minority of endometrial carcinoma patients (4.5%), but does not appear to affect their overall outcome. Although this is a small single site study, it raises questions about the value of this procedure in patients with endometrial cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The internationally agreed-upon purpose for standardized cancer staging is to enable and facilitate the clear and unambiguous communication of clinical and surgical experience among interested parties.1, 2, 3 Since cancer staging is essentially a categorization of patients based on the extent of a tumor's anatomic spread from its primary site, it should also categorize patients into prognostically distinct groups, in which those patients in a given stage are more comparable to other patients in that stage than they are to patients from the other stages with respect to clinical outcome.1, 3 In cancers of the endometrium, as with most malignant tumors of most organs, stage is the most powerful prognostic parameter.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 The determination of the extent of anatomic spread of endometrial cancers has traditionally been achieved ‘clinically’. Clinical staging entailed the use of various combinations of fractional curettage, uterine ultrasound and pelvic examination, as outlined in the 1971 annual report of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO).9 However, several studies published subsequently showed that clinical staging had an unacceptably high inaccuracy rate, failing to detect extra-uterine spread of disease in at least 15–20% of cases.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 Additionally, one of the main reasons for clinical staging, the administration of preoperative radiotherapy, fell into disfavor among gynecologists in the mid-1980s. Thus, following the tri-annual meeting of the oncology committee of FIGO in 1988, it was recommended that all endometrial cancers be surgically staged if the patient has an acceptable risk-to-benefit ratio for surgery.17, 18 This has since gained widespread acceptance and in their latest report, 92% of all endometrial cancers that were reported to FIGO were surgically staged.9

One routinely performed component of surgical staging is peritoneal washing. Originally described in 1956 for ‘detecting early spread’ of ovarian cancers,19 this procedure soon gained widespread use in the evaluation of endometrial cancers as well. The principal purpose of peritoneal washing is the potential detection of occult extra-uterine spread of disease in patients that otherwise would have been considered FIGO stage I (tumor confined to the uterine corpus) or stage II (tumor confined to the uterine corpus and cervix). In patients with endometrial cancers, the prognostic value of peritoneal washings was initially investigated in detail by Creasman and Rutledge in 1971.20 Using a cohort of 183 patients who all received preoperative radiotherapy, the authors reported an incidence of positive washings of 11.5%. Furthermore, they demonstrated worse survival at 4 years for patients with positive washings as compared to their counterparts with negative washings.20 The adverse impact of positive washings on overall survival was maintained even in patients with carcinoma that was limited to the endometrium and/or myometrium.20 Numerous studies have since been published on the prognostic significance of positive washings in endometrial carcinoma, with contradicting results.21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57 The incidence of positive washings in clinical stage I endometrial carcinoma in these studies ranged from less than 3% to almost 30%, a level of discrepancy which is illustrative of the overall lack of consensus on this subject. Nonetheless, in the FIGO staging scheme9 for endometrial cancers (as well as the closely related TNM staging1 of the American Joint Committee on Cancer), a positive finding on a peritoneal washing, presumably indicating extra-uterine spread of disease, places a patient in a late stage category (stage IIIA). Thus, the clinical and cost justification for the routine performance of this procedure derives mainly from the frequency with which it upstages patients with endometrial cancer, and perhaps more importantly, the prognostic significance of such an upstaging. In this report, we explore both these issues in detail. Using the database of a representitive cytology service at a large tertiary care academic medical center, we determined the frequency with which peritoneal washing findings alone upstaged patients with endometrial carcinoma. Then, using the same database, we investigated the prognostic significance of a positive peritoneal washing (when identified in the absence of other evidence of extrauterine disease) compared to stage-matched cases with negative washings. Our results challenge not only the justification for this procedure but the FIGO staging scheme's categorization of patients with an isolated positive washing as stage III.

Methods and patients

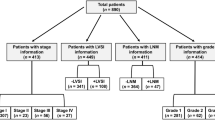

The cytologic reports of all peritoneal washings that were performed during the surgical staging of endometrial carcinomas during a 5-year period (01/1995–12/1999) were retrieved from the computerized database of the Pathology Department at Yale-New Haven Hospital (New Haven, CT, USA) and reviewed. Only cases in which carcinoma was diagnosed either in the prehysterectomy endometrial curettage and/or in the hysterectomy specimen were included in this study. Thus, washings performed for endometrial glandular hyperplasias (with or without atypia) were excluded. Cases that were not unequivocally diagnosed as negative for malignant cells were then separated and investigated in more detail, including a review of medical records, cytologic slides and the entire pathologic records.

A peritoneal washing typically involves the installation of approximately 100 cm3 of normal saline into the peritoneal cavity immediately upon entry. The fluid is allowed to bath the peritoneal surfaces and is then aspirated from the pelvic region. Cytologic slides are prepared in our laboratory using the ThinPrep® 2000 automated slide processor (Cytyc, Boxborough, MA, USA), per manufacturer's instructions.

A patient was deemed to have been upstaged by positive washings alone if, in the absence of washings, the patient would have been considered FIGO stage I or II (study group). Thus, in these patients, the surgeon noted no grossly evident intraperitoneal disease and on histologic sections, their endometrial cancers were confined to the uterine corpus and/or cervix without involvement of the uterine serosae. To create an age-matched control group of randomly selected patients with early-stage endometrial cancers with similar histologic subtypes but negative peritoneal washings, a database of all washings for FIGO stage I and II endometrial carcinomas performed over this period was constructed. The cases were listed consecutively based on the date of washing. For the purposes of matching the patients in the case group, they were also included in this database, each in their appropriate position based on the date of washing. Controls around each patient in the case group were selected as follows: The first patient preceeding and subsequent to the case group patient were selected from the list if (1) they were within 3 years of age of the study group patient and (2) their endometrial carcinoma was of the same histologic subtype. In both groups, patients with FIGO stage 1A and 1B, FIGO grade 1 and nuclear grade 1 endometrioid carcinoma received a simple hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (Hyst-BSO) only. All other patients with more adverse parameters (nonendometrioid histology, FIGO stage 1c or 2, nuclear grade 2 or above) also received at least bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomies in addition to their Hyst-BSO. None of the patients in both groups received preoperative radiotherapy. Methods of treatment, overall survival and any evidence of tumor progression (recurrence or metastases) were investigated and recorded for all the patients in both groups.

Results

Of 220 endometrial carcinomas, peritoneal washing cytology was unequivocally reported as ‘negative’ for malignant cells in 201 (91. 4%). The remaining 19 cases (8.6%) were ‘positive for malignant cells’ (n=14, 6.4%), ‘suspicious for malignant cells’ (n=2, 0.9%), or ‘atypical, suggestive of malignancy’ (n=3, 0.14%). All slides were reviewed and file diagnoses were confirmed. The following cytologic features characterized cases that were unequivocally diagnosed as malignant: several clustered, three-dimensional, scalloped-edged aggregates of large cells with vesicular to hyperchromatic nuclei that typically displayed prominent macronucleoli. The ‘suspicious’ cases were typically single cells, overall quantitatively less as compared to the ‘positive’ cases but largely retaining the same nuclear features. The three ‘atypical’ cases showed two or three clusters of enlarged cells with hyperchromatic nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, regular nuclear membranes, wisps of eosinophillic cytoplasm and an unaltered nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio. For the purposes of this study, ‘positive’, ‘suspicious’ and ‘atypical’ cases were all lumped into one group representing ‘abnormal’ peritoneal washings. Of 19 cases in this group, positive cytology alone was upstaged only 10 patients (4.5% of all cases). The histologic subtypes were endometrioid (n=8), serous (n=1), mixed (n=1). Nine of 10 cases were upstaged from FIGO stage IA or IB and one was upstaged from FIGO stage IIB. These 10 patients constituted our ‘case group’, and their detailed clinicopathologic information is outlined in Table 1. The washings in 70% of these 10 cases were unequivocally diagnosed as ‘positive’, 20% as ‘suspicious’ and 10% as ‘atypical’. Adjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy and/or hormonal therapy was administered in 90% of the patients in the case group. After a median follow-up of 51 months (range 6–94), no single patient had experienced disease progression, defined as tumor recurrence, metastasis or death. The 19 randomly selected patients in the control group ranged in age from 41 to 82 years. Adjuvant therapy was administered in 74% of this group. After a median follow-up of 63 months (range 4–107), only one patient had experienced disease progression. In this patient, radiologic evidence of a pulmonary metastatic deposit was identified 2 years after her hysterectomy. She was placed on a strong progestin (Megace) with subsequent reduction in the size of the lesion (as assessed radiographically) over a 6-month period. The mass has subsequently been stable and she shows no other evidence of disease progression with a total of 52 months of additional follow-up. The remaining 18 patients have remained disease-free over their period of follow-up. The clinicopathologic characteristics of the study and control group patients are compared in Table 2. Various clinicopathologic parameters in the case group and study group were compared using the Fisher's exact test. As expected, no significant difference was found (P>0.05).

Discussion

‘Management in this situation is controversial if no other features of extra-uterine disease have been documented at the time of surgical staging, because insufficient data exist regarding recurrence risk and treatment results’.58

The above statement from the latest Staging Classifications and Clinical Practice Guidelines of Gynaecologic Cancers, a joint publication of consensus guidelines from FIGO and the International Gynecologic Cancer Society, is illustrative of the difficulties encountered by clinicians in assessing the significance of positive peritoneal washings in early stage endometrial cancer. Thus, currently, under the same set of clinicopathologic circumstances, some patients receive no further therapy while others receive adjuvant therapy. Since peritoneal washings have been in routine use for almost half a century, and since the conclusive identification of a possible prognostic significance of positive washings continues to remain elusive, the logical question arises as to whether the whole concept of routine peritoneal washings for endometrial cancers require a re-evaluation. Pursuant to this effort, we have assessed the frequency with which cytology alone was upstaged patients with endometrial carcinoma over a 5-year period at a large academic medical center. Additionally, we investigated whether an isolated positive washing in patients with early stage endometrial carcinoma confers upon affected patients an overall worsening of clinical outcome. Our results show that a small but not insignificant percentage of patients (4.5%) will be upstaged by cytologic findings alone. This figure is lesser than the 11.4% average incidence found by McLellan et al39 in their literature meta-analysis that included 3091 patients in 15 studies. However, as previously noted, the incidence of positive washings reported in individual studies varied significantly, from 2.9%55 to 29.8%.34 Additionally, those studies were all carried out prior to the FIGO staging recommendations of 1988, and as the authors noted, the vast majority of the patients in those series received preoperative radiation.39 More recent studies, such as those of Obermair et al49 and Hirai et al,59 have shown more consistent figures of less than 5%. One notable exception is the recently reported study of Takeshima et al,56 in which a positive washing incidence of 18% was identified for their ‘low-risk’ group of patients.

This study also showed that endometrial cancer patients upstaged based on abnormal peritoneal washing cytology alone have no worse an outcome than do age—and tumor histologic subtype—matched patients with stage I or II endometrial cancer whose washings were negative. Our findings are in concordance with most similar studies published since the surgical staging recommendations of FIGO (1988) were routinely implemented at most centers.23, 43, 47, 48, 51, 56 As noted by Obermair et al,49 studies performed prior to 1990 showed more mixed results. We speculate that in the latter studies, at least a subset of clinically staged patients whose adverse outcomes were being attributed to the implications of positive washings, actually had occult extra-uterine disease elsewhere. One potential limitation of this study is that most of the patients in our case group received some form of posthysterectomy therapy. The natural history of any neoplastic process is, of course, best studied in the absence of any therapeutic interference. In this setting, that would entail a prospective study in which clinical stage I patients with positive washing cytology receive no further treatment and are compared either with an appropriately matched control group with negative cytology60 or randomized into treatment and nontreatment arms. This type of study is fraught with potential difficulties related to rarity of the study event (ie upstaging endometrial cancer patients based on peritoneal cytology alone), the number of years it would take to complete such a study and some ethical considerations. Thus, such a study is unlikely to be conducted. We believe the potential bias from treatment in this study is ameliorated somewhat because the majority of patients in both the case group and the control group received adjuvant therapy, creating a mutual offset. No patient in the study group experienced disease progression, rendering unnecessary the stratification of patients in this small group based on treatment differences.

The presence of malignant cells in peritoneal washings as an indication that there is extra-uterine spread of disease seems intuitive, and their presence is assigned the full implications of extra-uterine disease as evidenced by their stage IIIA placement in the FIGO staging system.9 However, tumor metastasis is a complex multi-factorial process, and it is estimated that only a small percentage of circulating cells that exit their primary site actually survive, achieve autonomous growth and thus initiate a metastatic focus.61, 62, 63 This was well illustrated in the recent report of Hirai et al.59 In that elegant study, a cohort of 55 endometrial cancer patients with positive washings had intraabdominal tubes placed during their primary operations for the purpose of subsequently obtaining fluids for cytologic analysis. Although all patients had positive washings at the start of the study, by day 14, all but one of 34 patients (with stage I or II endometrial cancer) had negative washings. This ‘regression’ of tumor cells would explain why positive washings appear not to adversely impact the overall survival of patients with early stage endometrial cancers in recent studies. There is now emerging evidence that a significant innate and adaptive immunity exists in the peritoneum that prevents the successful growth and propagation of tumor cells.64 This immunity may be subverted by some tumors, allowing them to grow. The malignant potential of tumor cells within the peritoneal cavity may also be related to the number of tumor cells. In the study of Szpak et al,26 the concentration of malignant cells in washings correlated with overall survival in stage I endometrial carcinoma patients: four patients with malignant cells >1000 cells/100 ml of washing sample died of disease within 2 years of surgery, the other eight patients with lesser concentrations of malignant cells experienced no disease progression during the follow-up period. Although much about the pathogenesis of the tumor–peritoneum interaction remains to be elucidated, the above findings indicate that at minimum, positive washings may not be synonymous with the normally understood biologic implications of true metastases.

Based on the findings in this and other recent studies,23, 43, 47, 48, 51, 56 an argument can be made against the routine performance of peritoneal washings during the surgical staging of patients with endometrial carcinoma. For a procedure that is performed on all patients, only a small proportion of them are upstaged exclusively by the results of this procedure. More importantly, most of the recent studies have failed to demonstrate any worsening of overall outcome in those patients with early stage cancer who are upstaged solely based on abnormal washings.23, 43, 47, 48, 51, 56 In an analysis of recent studies (studies published after the surgical staging recommendations of FIGO (1988) can reasonably be expected to have been routinely implemented in most centers (ie 1990 and beyond)), six of nine studies (66.7%) demonstrated that peritoneal washing cytology alone is of no significant independent prognostic value in early stage endometrial cancers. At an approximate cost of $40 (billable cost for pathology, excluding surgical and specimen transport expenses), the peritoneal washing is a relatively cheap as well as easy-to-perform test. However, in the absence of a demonstrable independent clinical impact, this cost to patients and the healthcare system, minimal as it may be, hardly seems justifiable. Many physicians currently ignore the results of washings while others treat aggressively based on it. The latter has included progestins, chemotherapy, abdominal radiation and intraperitoneal chromic phosphate.28, 29, 32, 39, 65 However, if washings are capturing intraperitoneal malignant cells at a point in time in which they have not established autonomous growth and were destined for necrosis, these patients may be receiving unnecessary adjuvant therapy.

The contrary argument, for the continued routine performance of peritoneal washings, also has several supporting points. It is not in dispute that positive peritoneal washings provide some prognostic information. When patients with endometrial cancer are considered as a group, positive washings correlates consistently across several studies with established prognostic parameters such as advanced tumor stage, advanced histologic grade, lymph node metastases, depth of myometrial invasion, and even recurrence and survival.23, 25, 39, 41, 62, 63, 66, 67 What is more controversial is whether they provide independent prognostic information in early stage cancer patients after covariates have been excluded. For those patients with stage I and stage II endometrial cancers of low histologic grade, positive washings probably have no independent impact on disease recurrence rates or survival as discussed above.68 Washings may, however, be used to guide therapy for a subset of patients with early stage type II endometrial cancers. For example, it is well established that endometrial serous carcinoma may exist as a small, endometrium-confined focus, and still show extrauterine metastases.69, 70, 71 Thus, a positive washing in this setting is more likely to represent true extra-uterine spread of disease, and Chen and Berek.65 administer adjuvant chemotherapy such as paclitaxel and carboplatin for these patients. However, the dominant prognostic parameter here is likely nonendometrioid histology, not the positive washing. In advanced stage patients, positive washings do not emerge as an independent adverse prognostic parameter on multivariate analyses, but may be of use when combined with other poor prognostic parameters to predict the risk of disease recurrence and overall survival.23, 56, 68 Since extent of disease is often unknown when washings are taken, this argues for the continued collection of peritoneal washings in all patients. Additionally, by no means is there consensus on the lack of prognostic significance of peritoneal washing cytology for clinical stage I patients upstaged by cytology alone, and a small minority of studies continue to demonstrate for this finding an adverse impact on overall survival. A study published as recently as 200149 showed that such patients had a significantly worse disease-free survival as compared with similar patients with negative washings (67 vs 96%, P<0.001). Zuna and Behrens44 and Kennedy et al25 also noted statistically significant survival differences when early stage patients with positive and negative washings were compared. Finally, as noted previously, the test is relatively cheap, easy-to-perform, and relatively complication-free.

If routine washings are continued, at minimum, the implications of positive washings in the staging of patients with endometrial cancer require a re-evaluation. In the current FIGO staging system,9 positive washings indicate stage IIIA disease, which categorizes such patients into the same group as others with ovarian or fallopian tube spread, and uterine serosal involvement. The heterogeneous nature of such a grouping was evident in a recent study in which stage IIIA patients were specifically investigated with respect to outcome.53 The authors concluded that for low-risk histologic subtypes (ie endometrioid carcinoma, which represents 80% of all endometrial carcinoma), adnexal and serosal involvement were both associated with a poor outcome, while positive peritoneal washing was not.53 Another study, in which stage IIIA patients were classified into two groups based on uterine serosa/adnexal involvement or positive peritoneal washings alone, showed similar findings: overall survival at 5 years was 27% for the first group and 80% for the second.72 Boronow,2 a pioneer in gynecologic oncology, has also objected to this grouping, writing that serosal involvement should be viewed as an extreme of myometrial invasion, ‘quite a different entity from adnexal spread’. He also proposed that washing cytology results be applied to more stages of endometrial cancer, as they are with ovarian malignancies.1 We certainly agree that there needs to be greater discussion on whether positive washings alone should upstage these patients, and a reassessment of the placement of these patients in the FIGO staging system seems warranted.

In conclusion, we demonstrated in this study that positive cytology without other evidence of extra-uterine disease leads to upstaging of a minority of endometrial carcinoma patients (4.5%), but does not appear to affect their overall outcome. Although this is a small single-site study, it raises questions about the value of this procedure in patients with endometrial cancer as well as the stage IIIA placement of patients with positive results in the FIGO staging system. We encourage further consideration and study of these concepts.

References

Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al. Purposes and principles of staging. In: Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, Fritz AG, Balch CM, Haller DG, Morrow M, (eds). AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook, 6th edn. Springer-Verlag: New York, 2002;3–14.

Boronow RC . Surgical staging of endometrial cancer: evolution, evaluation and responsible challenge-a personal perspective. Gynecol Oncol 1997;66:179–189.

Benedet JL, Pecorelli S . Why cancer staging? Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2003;83(Suppl 1):3.

Kosary CL . FIGO stage, histology, histological grade, age and race as prognostic factors in determining survival for cancers of the female gynecological system: an analysis of 1973–1987 SEER cases of cancer of the endometrium, cervix, ovary, vulva, and vagina. Semin Surg Oncol 1994;10:31–46.

Prat J . Prognostic parameters of endometrial carcinoma. Hum Pathol 2004;35:649–662.

Abeler VM, Kjorstad KE . Endometrial carcinoma in Norway. A study of a total population. Cancer 1991;67:3093–4003.

Wolfson A, Sightler S, Markoe A, et al. The prognostic significance of surgical staging for carcinoma of the endometrium. Gynecol Oncol 1992;45:142–146.

Gal D, Recio FO, Zamurovic D . The new International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics surgical staging and survival rates in endometrial carcinoma. Cancer 1992;69:200–202.

Creasman WT, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P, et al. Carcinoma of the corpus uteri. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2003;83(Suppl 1):79–118.

Chen S . Extrauterine spread in endometrial carcinoma clinically confined to the uterus. Gynecol Oncol 1985;21:23–31.

Gusberg S . The problem of staging endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol 1966;28:305–308.

Fanning J, Alvarez P, Tsukada Y, et al. Prognostic significance of the extent of cervical involvement by endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 1991;40:46–47.

Soothill PW, Alcock CJ, MacKenzie IZ . Discrepancy between curettage and hysterectomy histology in patients with stage I uterine malignancy. Br J Obstet Gynecol 1989;96:478–481.

Tornos C, Silva EG, el-Nagger A, et al. Aggressive stage 1 grade 1 endometrial carcinoma. Cancer 1992;70:790–798.

Cowles T, Javier F, Masterson B, et al. Comparison of clinical and surgical staging in patients with endometrial carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol 1985;66:413–416.

Creasman WT, Morrow CP, Bundy BN, et al. Surgical pathologic spread patterns of endometrial cancer: a gynecologic oncology group study. Cancer 1987;60:2035–2041.

Creasman WT, Eddy GL . Recent advances in endometrial cancer. Semin Surg Oncol 1990;6:339–342.

Creasman WT . New gynecologic cancer staging. Obstet Gynecol 1990;75:287–288.

Keettel WC, Elkins HG . Experience with radioactive colloidal gold in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1956;71:553–568.

Creasman WT, Rutledge F . The prognostic value of peritoneal cytology in gynecologic malignant disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1971;110:773–781.

Morrow CP, Bundy BN, Kurman RJ, et al. Relationship between surgical–pathological risk factors and outcome in clinical stage I and II carcinoma of the endometrium: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 1991;40:55–65.

Wolfson AH, Sightler SE, Markoe AM, et al. The prognostic significance of surgical staging for carcinoma of the endometrium. Gynecol Oncol 1992;45:142–146.

Kadar N, Homesley HD, Malfetano JH . Positive peritoneal cytology is an adverse factor in endometrial carcinoma only if there is other evidence of extrauterine disease. Gynecol Oncol 1992;47:145–149.

Grigsby PW, Perez CA, Kuten A, et al. Clinical stage I endometrial cancer: prognostic factors for local control and distant metastasis and implication of the new FIGO surgical staging system. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1992;22:905–911.

Kennedy AW, Webster KD, Nunez C, et al. Pelvic washings for cytologic analysis in endometrial adenocarcinoma. J Reprod Med 1993;38:637–642.

Szpak CA, Creasman WT, Vollmer RT, et al. Prognostic value of cytologic examination of peritoneal washings in patients with endometrial carcinoma. Acta Cytol 1981;25:640–646.

Soper JT, Creasman WT, Clarke-Pearson DL, et al. Intraperitoneal chromic phosphate P32 suspension therapy of malignant peritoneal cytology in endometrial carcinoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1985;153:191–196.

Kennedy AW, Peterson GL, Becker SN, et al. Experience with pelvic washings with stage I and II endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 1987;28:50–60.

Mazurka JL, Krepart GV, Lotocki RJ . Prognostic significance of positive peritoneal cytology in endometrial carcinoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1988;158:303–306.

Imachi M, Tsukamoto N, Matsuyama T, et al. Peritoneal cytology in patients with endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 1988;30:76–86.

Konski A, Poulter C, Keys H, et al. Absence of prognostic significance, peritoneal dissemination and treatment advantage in endometrial cancer patients with positive peritoneal cytology. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1988;14:49–55.

Creasman WT, Disaia PJ, Blessing J, et al. Prognostic significance of peritoneal cytology in patients with endometrial cancer and preliminary data concerning therapy with intraperitoneal radiopharmaceuticals. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1981;141:921–929.

Yazigi R, Piver MS, Blumenson L . Malignant peritoneal cytology as prognostic indicator in stage I endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol 1983;62:359–362.

Ide P . Prognostic value of peritoneal fluid cytology in patients with endometrial cancer stage I. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1984;18:343–349.

Boronow RC, Morrow CP, Creasman WT, et al. Surgical staging in endometrial cancer: clinicalpathologic findings of a prospective study. Obstet Gynecol 1984;63:825–832.

Heath R, Rosenman J, Varia M, et al. Peritoneal fluid cytology in endometrial cancer: its significance and the role of chromic phosphate (32P) therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1988;15:815–822.

Harouny VR, Sutton GP, Clark SA, et al. The importance of peritoneal cytology in endometrial carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol 1988;72:394–398.

Brewington KC, Hughes RR, Coleman S . Peritoneal cytology as a prognostic indicator in endometrial carcinoma. J Reprod Med 1989;34:824–826.

McLellan R, Dillon MB, Currie JL, et al. Peritoneal cytology in endometrial cancer: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1989;44:711–719.

Hirai Y, Fujimoto I, Yamauchi K, et al. Peritoneal fluid cytology and prognosis in patients with endometrial carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol 1989;73:335–338.

Lurain JR, Rumsey NK, Schink JC, et al. Prognostic significance of positive peritoneal cytology in clinical stage I adenocarcinoma of the endometrium. Obstet Gynecol 1989;74:175–179.

Turner DA, Gershenson DM, Atkinson N, et al. The prognostic significance of peritoneal cytology for stage I endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol 1989;74:775–780.

Grimshaw RN, Tupper WC, Fraser RC, et al. Prognostic value of peritoneal cytology in endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 1990;36:97–100.

Zuna RE, Behrens A . Peritoneal washing cytology in gynecologic cancers: long-term follow-up of 355 patients. J Natl Cancer Inst 1996;88:980–987.

Mathew S, Erozan YS . Significance of peritoneal washings in gynecologic oncology. The experience with 901 intraoperative washings at an academic center. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1997;121:604–606.

Gu M, Barakat RR, Thaler HT, et al. Peritoneal washings in endometrial carcinoma. A study of 298 patients with histopathologic correlation. Acta Cytol 2000;44:783–789.

Ebina Y, Hareyama H, Sakuragh N, et al. Peritoneal cytology and its prognostic value in endometrial carcinoma. Int Surg 1997;82:244–248.

Vecek N, Marinovic T, Ivic J, et al. Prognostic impact of peritoneal cytology in patients with endometrial carcinoma. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 1993;14:380–385.

Obermair A, Geramou M, Tripcony L, et al. Peritoneal cytology: impact on disease-free survival in clinical stage I endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the uterus. Cancer Lett 2001;164:105–110.

Descamps P, Calais G, Moire C, et al. Predictors of distant recurrence in clinical stage I or II endometrial carcinoma treated by combination surgical and radiation therapy. Gynecol Oncol 1997;64:54–58.

Milosevic MF, Dembo AJ, Thomas GM . The clinical significance of malignant peritoneal cytology in stage I endometrial carcinoma. Int. J Gynecol Cancer 1992;2:225–235.

Kashimura M, Sughihara K, Toki N, et al. The significance of peritoneal cytology in uterine cervix and endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 1997;67:285–290.

Preyer O, Obermair A, Formann E, et al. The impact of positive peritoneal washings and serosal and adnexal involvement on survival in patients with stage IIIA uterine cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2002;86:269–273.

Hernandez E, Rosenshein N, Dillon MB, et al. Peritoneal cytology in stage I endometrial cancer. J Natl Med Assoc 1985;77:799–803.

Burrell MO, Franklin III EW, Powell JL . Endometrial cancer: evaluation of spread and follow-up one hundred eighty-nine patients with Stage I or Stage II disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1982;144:181–185.

Takeshima N, Nishida H, Tabata T, et al. Positive peritoneal cytology in endometrial cancer: enhancement of other prognostic indicators. Gynecol Oncol 2001;82:470–473.

Santala M, Talvensaari-Mattila A, Kauppila A . Peritoneal cytology and preoperative serum CA 125 level are important prognostic indicators of overall survival in advanced endometrial cancer. Anticancer Res 2003;23:3097–3103.

Benedet JL, Hacker NF, Ngan HYS . Cancer of the corpus uteri In: Benedet JL, Hacker NF, Ngan HYS (eds). Staging Classifications and Clinical Practice Guidelines of Gynaecologic Cancers, 2nd edn. http://www.figo.com, Accessed 06/12/04.

Hirai Y, Takeshima N, Kato T, et al. Malignant potential of positive peritoneal cytology in endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol 2001;97:725–728.

Sutton GP . Peritoneal cytology in endometrial carcinoma. Cancer Treat Res 1989;49:41–52.

Tarin D . Cancer metastasis. In: Peckham M, Pinedo H, Veronesi U (eds). Oxford Textbook of Oncology. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1995, pp 118–132.

Fidler IJ . Molecular biology of cancer: invasion and metastasis. In: DeVita Jr VT, Hellmann S, Rosenberg SA (eds). Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology, 5th edn. Lippincott-Raven Publishers: Philadelphia, 1997, pp 135–152.

Abati A, Liotta LA . Looking forward in diagnostic pathology. The molecular superhighway. Cancer 1996;78:1–3.

Melichar B, Freedman RS . Immunology of the peritoneal cavity: relevance for host–tumor relation. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2002;12:3–17.

Chen LM, Berek JS . Staging and treatment of endometrial cancer. http://www.uptodateonline.com, Accessed 06/11/04.

Lurain JR, Rice BL, Rademaker AW, et al. Prognostic factors associated with recurrence in clinical stage I adenocarcinoma of the endometrium. Obstet Gynecol 1991;78:63–69.

Zaino RJ, Kurman RJ, Diana KL, et al. Pathologic models to predict outcome for women with endometrial cancer. The importance of the distinction between surgical stage and clinical stage—a gynecologic oncology group study. Cancer 1996;77:1115–1121.

Lurain JR . The significance of positive peritoneal cytology in endometrial cancer [editorial]. Gynecol Oncol 1992;46:143–144.

Silva EG, Jenkins R . Serous carcinoma in endometrial polyps. Mod Pathol 1990;3:120–128.

Lee KR, Belinson JL . Recurrence in noninvasive endometrial carcinoma. Relationship to uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1991;15:965–973.

Wheeler DT, Bell KA, Kurman RJ, et al. Minimal uterine serous carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2000;24:797–806.

Chen MD, Karlan BY, Muderspach LI, et al. Is positive peritoneal cytology sufficient for stage IIIA endometrial cancer? In: Abstracts of Current Clinical and Basic Investigation of the 40th Annual Clinical Meeting April 27–30, 1992. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Abstracts, Washington DC, 1992, p 13.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

A preliminary version of this study was presented at Pathology Today®, the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Pathologists (ASCP), San Antonio, TX, October 7–10, 2004.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fadare, O., Mariappan, M., Hileeto, D. et al. Upstaging based solely on positive peritoneal washing does not affect outcome in endometrial cancer. Mod Pathol 18, 673–680 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800342

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800342

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Prognostic significance of peritoneal cytology in low-risk endometrial cancer: comparison of laparoscopic surgery and laparotomy

International Journal of Clinical Oncology (2021)

-

Is Peritoneal Cytology an Independent Prognostic Factor in Early-Stage Endometrial Cancer?

Indian Journal of Gynecologic Oncology (2021)

-

Iatrogenic transtubal spill of endometrial cancer: risk or myth

Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2011)

-

Hysteroscopy and endometrial cancer. Diagnosis and influence on prognosis

Gynecological Surgery (2010)