Abstract

Study design: A case of thoracic spinal cord compression due to tumoral calcinosis (TC) is reported.

Setting: Galiza, Spain.

Case report: A 59-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with a 2-month history of gradual leg weakness and sensory deficit. The neurological examination revealed paraparesis with T12 sensory level. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an extradural right posterolateral mass at T11–T12 level, resulting in a marked spinal cord compression. He underwent T11–T12 laminectomy and mass excision. Histological examination finally led to the diagnosis of TC.

Conclusion: TC is an uncommon cause of mass lesions of the spine. Since there is no typical spine TC MRI appearance, the final diagnosis is done by histological studies. TC should be considered in differential diagnosis of spinal cord compression and constitutes a treatable cause of paraparesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tumoral calcinosis (TC) is a distinct clinical and histological entity that is characterized by tumor-like periarticular deposits of calcium. It is usually located in the soft tissues around the large joints of the body, especially hips, elbows and shoulders. TC involving the spine is uncommon. The principal manifestation of the disease is the presence of a subcutaneous calcified mass that is usually asymptomatic and only rarely causes discomfort, tenderness, ulceration or pain, the neurological involvement being exceptional.1,2 Little is known about the exact etiology and several hypotheses have been suggested.1,2,3,4

Spinal involvement is rare, and to the best of our knowledge, TC of the thoracic spine has been reported only once before.5 We describe an exceptional case of a patient with paraparesis caused by TC located in the thoracic spine, which was totally resected. No recurrence could be observed in the follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans obtained 2 years later.

Case report

History

A previously healthy 59-year-old Spanish man was admitted to our hospital with a 2-month history of gait disturbance because of gradual leg weakness and sensory deficit.

Physical examination

Neurological examination revealed leg weakness with muscle strength of 2/5 (MRC scale) and sensory level at dermatome T12. Position and vibration sensation were severely impaired. Cremasteric, anal and bulbocavernous reflexes were normal with left low abdominal reflex absent. Babinski sign was present bilaterally. The ASIA Impairment Scale was at C level.

Laboratory and diagnostic imaging studies

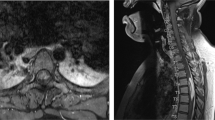

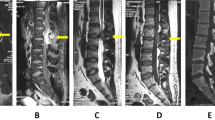

All laboratory tests were normal. Dorsolumbar plain X-ray showed moderate spondylotic changes. MRI scans revealed a extradural right posterolateral rounded mass at the T11–T12 level, resulting in a marked spinal cord compression. This mass was isointense in T1-weighted images, and hyperintense in T2-weighted images. After gadolinium administration some enhancement at the margins of the lesion was observed. Sinovial cyst was considered as the first diagnostic possibility (Figures 1 and 2).

Surgery

Total T11–T12 laminectomy and mass excision were performed.

Histological examination

Study of the surgically removed specimen showed an unencapsulated mass consisting of dense fibrous tissue containing spaces filled with gray, pasty, calcareous material. Microscopically, it was an amorphous or granular calcified material, mostly surrounded by fibrous tissue and focally bordered by mono- and multinuclear macrophages and chronic inflammation (Figure 3), without evidence of neoplasia.

Postoperative course

The postoperative course was uneventful. The patient underwent physical therapy improving muscular strength but mild ataxic spinal gait is still present. The ASIA scale changed to D level. No signs of recurrence were observed at follow-up evaluation 2 years after surgery. No instability findings could be demonstrated in the MRI and X-ray images.

Discussion

The etiology of this entity is still unknown, and no general agreement exists regarding its pathogenesis.1,4,6,7

In a review by Smack et al,3 121 cases of TC were identified. They suggest three pathogenetically distinct subtypes: (1) Primary normophosphatemic TC without metabolic abnormalities, with no evidence of familial patterns. Nearly half of the patients live in tropical regions of the world. (2) Primary hyperphosphatemic TC with strong familial patterns. (3) Secondary TC with concurrent disease capable of causing soft tissue calcification as chronic renal failure, hyperparathyroidism, hypervitaminosis D, scleroderma, pseudoxanthoma elasticum, malignancy and milk-alkali syndrome.

Previously Tezelman et al,2 in the largest series reported up to date, identified 282 cases, of which 66 (23%) had a known abnormality of calcium metabolism, whereas 216 (77%) did not.

Our patient had no family history, biochemical abnormalities or underlying medical condition known to promote soft tissue calcification. For that reason, we have considered this case as idiopatic or primary TC, type 1 of the Smack classification.

Until the present date, in only two reports has TC been pointed out as the cause of spinal cord compression. Watanabe et al,8 described a case of paraparesis in a patient with TC in the dura mater of the lumbar spine. More recently, Durant et al,5 reported some cases showing a severe cord compromise, from a series of 21 patients with TC involving spine. Four patients showed lesions in the thoracic spine as observed in our patient. In this report, however, the neurological level exhibited for these patients is not clearly stated, nor is the direct cause–effect relationship between the calcified mass and the spinal cord injury, since, as reported by the authors, previous pathologies (eg compression fracture, history of cancer, severely osteoporotic spines) could not be discarded as the primary cause of the observed spinal cord damage.

In the case presented in this paper, the clinical picture, with a higher degree of involvement of the posterior columns, is fully explained by the calcified extradural mass located in the posterolateral region of the spinal canal.

Unlike previous reports, in our case calcification was not detected in plain X-rays. Calcification was not detected until the MRI scans were made, probably because the mass lesion was small. The MRI revealed a spindle-shaped extradural lesion. This mass was isointense in T1-weighted images and hyperintense in T2-weighted images. MRI scans after gadolinium administration gave some enhancement at the margins of the lesion. These MRI features are similar to those described by Watanabe et al.8 Other authors5,9,10 have reported, however, that TC masses were hypointense in T1-weighted images, and mixed hypointense and isointense in T2-weighted images. Furthermore, Durant et al5 stated as a characteristic feature the fact that gadolinium did not enhance the lesions. Since there is no typical spine TC MRI appearance, the final diagnosis is made by histological studies.

Durant et al5 propose that spinal TC may be common in this location as a result of pre-existing degenerative changes. This statement should be corroborated by further spinal TC reports, with lesions located in the areas more exposed to degenerative changes such as intervertebral spaces and facets. Moreover, due to the rising number of spinal MRI studies practiced every year, we could expect an elevated number of suspicious lesions of TC.

Total surgical excision of the calcium deposits seems to be an adequate treatment in patients with unknown origin of the disease, as is described in the literature2,9,10,11 In our case, no regrowth was seen in neuroimaging at the 2-year follow-up.

In conclusion, TC should be considered in differential diagnosis of spinal cord compression and constitutes a treatable cause of paraparesis.

References

Weiss SW, Goldbum JR . Benign soft tissue tumors of uncertain type. In: Enzinger FM, Weiss SW (eds). Soft Tissue Tumors. 4th edn. Mosby: St Louis, MI 2001, pp 1419–1481.

Tezelman S, Siperstein AE, Duc QY, Clark OH . Tumoral calcinosis. Arch Surg 1993; 128: 737–745.

Smack DP, Norton SA, Fitzpatrick JE . Proposal for a pathogenesis-based classification of tumoral calcinosis. Int J Dermatol 1996; 35: 265–271.

Abraham Z, Rozner I, Rozenbaum M . Tumoral calcinosis: report of a case and brief review of the literature. J Dermatol 1996; 23: 545–550.

Durant DM, Riley LH, Burger PC, McCarthy EF . Tumoral calcinosis of the spine. Spine 2001; 26: 1673–1679.

Prasad VLN et al. Tumoral calcinosis. World J Surg 1989; 13: 803–808.

Garcia S et al. Compression of the sciatic nerve in uremic tumoral calcinosis. Neurologia 1999; 14: 86–89.

Watanabe A, Isoe S, Kaneko M, Nukui H . Tumoral calcinosis of the lumbar meninges: case report. Neurosurgery 2000; 47: 230–232.

Ohashi K et al. Idiopatic tumoral calcinosis involving the cervical spine. Skeletal Radiol 1996; 25: 388–390.

Kokubun S, Ozawa H, Sakuri M, Tanaka Y . Tumoral calcinosis in the upper cervical spine: a case report. Spine 1996; 21: 249–252.

Vaicys C, Schulder M, Singletary LA, Grigorian AA . Tumoral calcinosis of the lumbar spine: case illustration. J Neurosurg (Spine 1) 1999; 91: 137.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Flores, J., Muñoz, J., Gallego, S. et al. Spinal cord compression due to tumoral idiopatic calcinosis. Spinal Cord 41, 413–416 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101419

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101419

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Paraarticular osteochondroma of a cervico-thoracic facet joint presenting as myelopathy

Skeletal Radiology (2011)