Abstract

Numerous studies have indicated a link between the presence of polymorphism in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and cognitive and affective disorders. However, only a few have studied these effects longitudinally along with structural changes in the brain. This study was carried out to investigate whether valine-to-methionine substitution at position 66 (val66met) of pro-BDNF could be linked to alterations in the rate of decline in skilled task performance and structural changes in hippocampal volume. Participants consisted of 144 healthy Caucasian pilots (aged 40–69 years) who completed a minimum of 3 consecutive annual visits. Standardized flight simulator score (SFSS) was measured as a reliable and quantifiable indicator for skilled task performance. In addition, a subset of these individuals was assessed for hippocampal volume alterations using magnetic resonance imaging. We found that val66met substitution in BDNF correlated longitudinally with the rate of decline in SFSS. Structurally, age-dependent hippocampal volume changes were also significantly altered by this substitution. Our study suggests that val66met polymorphism in BDNF can be linked to the rate of decline in skilled task performance. Furthermore, this polymorphism could be used as a predictor of the effects of age on the structure of the hippocampus in healthy individuals. Such results have implications for understanding possible disabilities in older adults performing skilled tasks who are at a higher risk for cognitive and affective disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The neurotrophin family is considered recent in the evolutionary scale and has not been identified in Caenorhabditis elegans.1 It has been estimated that nerve growth factor and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) evolved ∼600 million years ago from a common ancestral gene.2 However, unlike nerve growth factor, BDNF has been remarkably conserved in lower vertebrates and in mammals with ∼90% homology between fish and mammalian BDNF. The extremely high conservation rate in the BDNF gene suggests that alterations in this gene have not been evolutionarily tolerated.2 For this reason, the occurrence of single-nucleotide polymorphism(s) (SNPs) in BDNF may lead to significant structural and functional consequences. BDNF binding and internalization have been shown to have important roles in neuronal survival, differentiation,3 axonal path finding,4 regulation of dendritic trafficking to post-synaptic densities,5 protection against neuronal death in the hippocampus6 and induction and maintenance of late-phase potentiation.7 Furthermore, reduced levels of cortical BDNF have been shown to correlate with the severity of pathology in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease (AD).8 These studies emphasize the fact that any abnormalities in BDNF would exert significant functional implications on the brain.

The most widely studied polymorphism in BDNF is val66met substitution (rs6265), which has consistently been linked to the occurrence of depression in elderly and adolescents,9, 10 depressive symptoms associated with AD11 and stroke.12 Other psychiatric conditions linked to this substitution include anorexia nervosa,13 anxiety-related disorders,14 depressive episodes in bipolar disorder,15 suicidal behavior,16 schizophrenia17 and introversion.18

The G-to-A substitution in the coding exon VIII of the BDNF gene (G196A) leads to substitution of amino-acid valine to methionine at position 66 of the pro-BDNF protein (val66met). The prevalence of this substitution has been found to be the highest in Asia (∼43%) and lowest in Sub-Saharan Africa (∼0.5%). In the United States, the prevalence of met carriers has been reported to be around 18–32%. Interestingly, small Native-American communities in Arizona show higher prevalence of met alleles (40%).19, 20

The val66met substitution occurs in the pro-domain of the BDNF protein and is thus unlikely to affect the intrinsic activity of mature BDNF. However, it seems that val66met substitution alters BDNF processing and thus the outcome of BDNF-TrkB signaling. It has been suggested that val66met substitution can alter the rate of activity-dependent BDNF release by (1) affecting its proper folding and sorting into secretory vesicles and/or (2) reducing its intracellular distribution: Within the Golgi apparatus, BDNF can be sorted into regulated (activity dependent) or constitutive secretory pathways. Sortilin, a member of the vacuolar protein sorting 10 family, is highly enriched in the Golgi apparatus and has an important role in BDNF processing.21 Through binding to the pro-domain region of BDNF, sortilin has an important role in sorting BDNF into the regulated secretory pathway. The occurrence of val66met substitution in this region leads to a significant decrease in BDNF interaction with sortilin21 thereby mis-sorting of BDNF into the constitutive secretory instead of the regulated secretory pathway (Figure 1). In neurons, BDNF is not exclusively synthesized in the somata. It has been shown that fragments of BDNF mRNA are transported from cell body to dendrites for local synthesis.22 BDNF gene expression is achieved by formations of two types of BDNF mRNA, those with short 3′ untranslated region and others with long 3′ untranslated region. The long 3′ untranslated region of the BDNF mRNA is transported to the dendrites, whereas the short 3′ untranslated region remains within the cell body.23 It has been suggested that by reducing interaction with translin, that is, an mRNA-binding protein, G-to-A substitution in the BDNF gene leads to failed translocation of BDNF mRNA to dendrites,24 thus reducing its intracellular distribution.

Schematic representation of possible mechanism by which val66met substitution in BDNF leads to failed activity-dependent release of BDNF or reduced intracellular transport. Val66met substitution changes the dynamics of interaction between BDNF and two important proteins: (1) Sortilin, is involved in intracellular sorting and pro-neurotrophin signaling. Val66met substitution leads to reduction of BDNF interaction with this protein, which results in mis-sorting into the constitutive secretory pathway instead of activity-dependent release. (2) Translin is a highly conserved protein involved in mRNA transport. An exon found in all BDNF mRNA splice variants contains a specific translin-binding region, which is essential for appropriate BDNF mRNA dendritic targeting. It has been shown that Val66met substitution diminishes BDNF mRNA interaction with translin, which leads to reduced translocation of BDNF mRNA to dendrites.

Owing to the critical role of BDNF in synaptic plasticity particularly in the hippocampus and the significant consequences of val66met substitution on BDNF processing and intracellular distribution, we asked whether this polymorphism can alter the rate of decline in skilled task performance along with changes in the hippocampal volume in the absence of any neurological or cognitive disorders.

Multiple studies have suggested that abnormalities in production, transport and signaling of BDNF have a significant role in affective disorders.25 Volumetric brain alterations particularly in the hippocampus have also been linked to BDNF polymorphism.26 Using a meta-analysis of 399 healthy individuals, Hajek et al.26 reported a significant reduction in bi-lateral hippocampal volume in met carriers. Furthermore, Cathomas et al.27 studied the relationship between multiple SNPs on the BDNF gene and verbal episodic memory. From 55 SNPs studied, only val66met polymorphism correlated, showing poorer performance in met carriers.28 However, no study has investigated the correlation between skilled task performance in healthy individuals and BDNF polymorphisms. Such information could help us in understanding the complex physiology of cognitive and affective alterations associated with normal aging in older individuals attempting to perform skilled tasks such as driving, aviation or operating machinery.

This study was carried out to investigate whether val66met substitution in BDNF can (1) predict the rate of decline in performance of skilled tasks, (2) lead to structural alterations in the hippocampus and (3) alter the pattern of relationship between aging and hippocampal volume. To address these questions, we investigated the rate of decline in the skilled task of piloting an aircraft as determined by a standardized flight simulator score (SFSS). Standard flight simulation is a reliable and highly quantifiable method for measuring executive functions that are dependent on several aspects of cognition, in particular memory and attention, shown by a significant correlation between SFSS and cognition measured by CogScreen-AE.29, 30

Materials and methods

Participants

Participants included 144 Caucasian pilots who completed a minimum of 3 annual visits (Table 1) as part of the ongoing longitudinal Stanford/VA Aviation Study, approved by the Institutional Review Board of Stanford University. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. Enrollment criteria included age older than 40 years, current Federal Aviation Administration medical certificate and currently flying. The participants were either recreational pilots, certified flight instructors or civilian air-transport pilots. Upon enrollment, participants were assigned to one of three levels of expertise based on their Federal Aviation Administration proficiency rating: (1) least expertise: VFR (qualified to fly under visual flight rules only); (2) moderate expertise: IFR (also qualified to fly under instrument flight rules); and (3) most expertise: CFII or ATP (certified flight instructor for IFR students or rated for flying air-transport planes). Each rating requires progressively more advanced training and more hours of training.31 Participants were healthy as determined by their regular physical and mental examinations performed by trained physicians. The absence of cognitive impairment was confirmed by CogScreen-AE, that is, a computerized battery for screening and monitoring cognitive abilities relevant to flying.32

Flight simulation

Standard flight simulation enabled us to investigate the ability to navigate an aircraft in a quantifiable and reproducible manner.33 We used a Frasca 141 flight simulator (Urbana, IL, USA), which simulates flying a small single-engine aircraft. Each individual went through six practice sessions and a 3-week break before the first baseline visit. The baseline visit and each visit thereafter consisted of morning and afternoon flights, 75-min in duration each, during which pilots had to face flight scenarios with emergency situations such as engine malfunctions and/or incoming air traffic. For each subsequent flight, several components were randomly varied and multiple versions of the flight scenario were presented to reduce learning of specific maneuvers and air traffic control messages. The scoring system produced 23 variables that measured a combination of the reaction time (in seconds) and deviations from ideal positions (altitude in feet, heading in degrees and airspeed in knots).33 Standardized Z-scores were computed to match different measurements. In addition, an overall flight performance summary score, that is, SFSS was computed. The scores collected represent the accuracy of executing the air traffic control commands, traffic avoidance, time to detect engine emergencies and executing a visual approach to landing. The primary measure of the outcome was the average rate of change per year in overall SFSS as determined by the slope of SFSS. Each flight simulation was followed by 40–60 min battery of cognitive tests including CogScreen AE.32 These tests were repeated annually.

Genotyping

Blood and saliva samples were collected during the first visit. We used an Illumina Bead Array platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) for high-throughput multiplexed SNP genotyping using Human 610 Quad gene chip. The system uses a high-density BeadArray technology in combination with an allele-specific extension, adapter ligation and amplification assay protocol.34 For quality control, Ilumina's BeadStudio Software (version 3.1) was used to validate the genotypes. Golden Helix SNP and Variation Suite (SVS Version 7.2.2, Bozeman, MT, USA) software was used for the analysis. As ApoE polymorphism markers were not present on HumanHap 650Y chip, a sample of the DNA was separately used for ApoE alleles determination,35 which led to successful genotyping in 98.6% of participants.

Imaging

Around one-third of participants (43 individuals) underwent structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) neuroimaging. From these, 65% (28 individuals) returned 1–2 times for follow-up imaging. The average time lag between the baseline simulator visit and the first MRI scan was 3.85 years (s.d.=3.0 years).

The MRI data were acquired at the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System on a 1.5-T (General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI, USA) MRI scanner. The following structural MRI sequences were performed on all participants using a standard head coil: (1) a spin-echo, sagittal localizer two-dimensional sequence of 5-mm thick slices; (2) a proton density and T2-weighted spin-echo MRI, repetition time/echo time1/echo time2=5000/30/80 ms, 51 oblique axial 3 mm slices covering the entire brain and angulated parallel to the long axis of the hippocampal formation (1.00 × 1.00 mm2 in plane resolution); and (3) three-dimensional spoiled gradient recalled acquisition in the steady state (GRASS) MRI of the entire brain, repetition time/echo time=9/2 ms, perpendicular to the long axis of the hippocampus.

The volume of the hippocampus was determined using high-dimensional brain warping software (Surgical Navigation Technologies, Louisville, CO, USA). The Surgical Navigation Technologies method has been validated and compared with manual tracing of the hippocampus before (left: r=0.92; right: r=0.91; n=60).36 This method, originally developed by Christensen et al.,37 has been used in numerous studies on AD,38, 39 aging36, 40, 41 and schizophrenia.42 The Surgical Navigation Technologies semi-automated technique involves manual placement of global and hippocampal landmarks, followed by automated atlas mapping. In this study, global landmarks were placed at external boundaries of the brain image (by manually adjusting the angle and dimension of a three-dimensional proportional box to fully enclose the brain). Next, 22 local landmarks were placed at the boundaries of the hippocampus: 1 at the head, 1 at the tail and 4 per image (that is, at the superior, inferior, medial and lateral boundaries) on 5 equally spaced images perpendicular to the long axis of the ipsilateral hippocampus. The automated hippocampal mapping algorithm applied a coarse transformation followed by a fine and fluid transformation to match the individual image to a template brain. The final output included numerical volumes of the right and left hippocampi. In this study, we report total hippocampal volumes, normalized to each subject's total intracranial volume.

Statistical analyses

The primary outcome for skilled task performance was SFSS.31 The average rate of change in SFSS was computed by calculating the slope of linear regression between SFSS and the number of three consecutive annual visits yielding a fitted slope. The analysis of variance and Student's t-tests were used to test the difference among met positive (met/val and met/met) and met negative (val/val) groups. A P-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics

A total of 144 individuals underwent 3 consecutive annual flight simulations. Of these, 55 (38.2%) were met carriers (met/val or met/met) and 89 (61.8%) were non-met carriers (val/val). The prevalence of met carriers was close to demographics reported in healthy individuals.43 As shown in Table 1, met carriers and non-met carriers were demographically similar. No significant differences were found in age and education levels between the two groups (Table 1). Both groups had average of 17 years of education. ApoE genotyping showed that 52% of the participants were ApoE33, 25% ApoE34, 16.6% ApoE23, 2.77% ApoE44, 1.38% ApoE22 and 0.69% were ApoE24. We found no significant effects of ApoE4 alleles on the rate of decline of SFSS (t=−0.673; P=0.5020, d.f.=140) and hippocampal volume (t=1.534, P=0.1286, d.f.=84).

Standard flight simulator score

Only the data derived from the first three consecutive annual visits were used for this part of study. The effect of polymorphisms in BDNF was investigated by quantifying the rate of decline in SFSS during three consecutive annual visits using a linear regression. The average rate of decline in SFSS over the next 2 years was significantly higher in met carriers than in non-met carriers (met carriers=−0.109±0.134 (n=55), non-met carriers=−0.036±0.165 (n=89), F=7.696, P=0.0060) (Figure 2).

The slope of the SFSS in individuals with and without val66met substitution. As shown, we found a significant (ANOVA, F=7.696, P=0.0060) reduction in the slope of flight simulator score in met carriers (mean±s.d., slope=−0.110±0.135, n=55) compared with non-met carriers (slope=−0.036±0.165, n=89) during the first 2 years of follow-up.

Effects of flight experience

No significant differences were found in mean log hours of flight between met and non-met carriers (met carriers=1913.7±2454 h; non-met carriers=2717.2±2845 h, t-value=1.733, P=0.0852, d.f.=142). To further test the possible effects of experience on the results, we compared a subgroup of individuals with very similar log hours (met carriers=559.9±184.81 h, non-met carriers=589.77±197.77 h). Our investigation showed a significant difference (P=0.0043, t-value=2.974, d.f.=56) in the average rate of decline in SFSS for met carriers compared with non-met carriers, indicating that the difference in the slope of the SFSS was not significantly influenced by flight experience.

Hippocampal volume

The total volume of the entire hippocampus (right plus left) normalized to the total intracranial volume was quantified in one-third of individuals during the course of the study.

Cross-sectional analysis

The total volume of the hippocampus was compared between met and non-met carriers. We found no significant effects of val66met substitution on the average hippocampal size for all visits (met-carriers=5.042±0.552 cm3, n=19, non-met carriers=5.026±0.487 cm3 n=24, F=0.047, P=0.8290). We also investigated the link between hippocampal volume and SFSS and found no significant correlation between the two parameters (r=−0.101, P=0.346), which was not affected by BDNF polymorphism (met carriers, r=−0.058, P=0.7290, non-met carriers r=−0.117, P=0.4140).

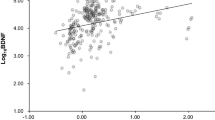

It has been shown that there is a negative correlation between hippocampal volume and age in healthy individuals.44 The question was raised whether val66met substitution can alter the pattern of relationship between hippocampal volume and age. Although we found no significant correlation between the age at MRI and the volume of hippocampus in non-met carriers (r=−0.178, P=0.2639), a significant negative correlation was detected between the two among met carriers (r=−0.447, P=0.0150). Furthermore, the slope of the age-related decline in hippocampal volume in met carriers (slope=−0.038) was two folds higher than that in non-met carriers (slope=−0.016) (Figure 3). Our results also showed that atrophy of the hippocampus became significant after the age of 65 years. Unlike non-met carriers who showed no difference in hippocampal volume before and after the age of 65 years, we found a significant shrinkage in hippocampal volume among met carriers after the age of 65 years (Figure 4).

The total volume of the hippocampus (both left and right) in individuals with and without val66met substitution. No significant differences were found in the size of the hippocampus, before and after 65 years in non-met carriers (before 65=100.0±9.63 and after 65=100.556±10.265: F=0.031, P-value=0.8610). However, there was a significant reduction in the size of the hippocampus in met carriers after the age of 65 years (before 65=104.654±9.938 and after 65=90.918±6.522, F=17.53, P-value=0.0001). As the result, we found a significant difference in the size of the hippocampus after the age of 65 years between met carriers and non-met carriers (F=7.207, P-value=0.014). The number of individuals in their sixth, seventh and eighth decades of life were 15, 15 and 6 among met carriers and 19, 26 and 5 among non-met carriers, respectively.

The relationship between the total volume of the hippocampus and the age and the effects of val66met substitution. Using a polynomial fitting curve, we found a (r=−0.447, P=0.0150) correlation between age and the volume of the hippocampus in met carriers. No such correlation was found in non-met carriers (r=−0.178, P=0.2639). Furthermore, the slope of the regression in met carriers (slope=−0.038) was twice the value of the slope of regression in non-met carriers (slope=−0.016).

Longitudinal analysis

Around 65% (n=28) of participants who underwent MRI, returned an average of 4.36±2.78 years later for follow-up imaging. The slope of hippocampal volume alterations for each individual was computed. The average slope of hippocampal volume alterations was quantified longitudinally among met carriers (n=12) and non-met carriers (n=16), even though the follow-up interval was not consistent. We found no significant effects of val66met substitution on the rate of decline in hippocampal volume (r=−0.089, P=0.6500, met carriers=−0.105±0.124 and non-met carriers=−0.084±0.118).

Discussion

In this study, we found that val66met substitution in BDNF could predict the rate of decline in skilled task performance in middle-aged and older healthy individuals. Furthermore, the rate of decline in hippocampal volume could be significantly affected by this substitution. These results are consistent with a significant reduction in hippocampal volume after the age of 65 years in met carriers as compared with non-met carriers, reported here.

Our finding of a two-fold increase in the rate of decline in SFSS among met carriers during the first 2 years of follow-up is consistent with the poorer performance and functioning of met carriers described by Egan et al..45 The negative effect of val66met substitution on the hippocampus and synaptic activity has been supported by decreased levels of N-acetyl-aspartate, an intracellular marker for neuronal and synaptic structural integrity.46 Furthermore, it has been shown that met carrier individuals show lower hippocampal activity than do non-met carriers during encoding and retrieval activities.47 This is supported by a number of studies reporting 11–15% reduction in the volume of hippocampus in healthy individuals with val66met substitution.48, 49, 50, 51, 52 The effect of age on hippocampal volume in met carriers has also been described in association with changes in the amygdala.53 Our results are also in concordance with studies that showed no effects of val66met substitution on hippocampal volume in younger adults.47 Interestingly, val66met substitution leads to lower scores in episodic memory in schizophrenic patients when compared with their healthy relatives.54 Finally, as already noted, BDNF abnormalities have been associated with affective abnormalities, which in turn might affect motivation and performance on cognitive tests and skilled tasks.

We did not find a significant correlation between SFSS and hippocampal volume in our healthy participants. This could be due to two reasons: (1) executive functioning is not solely dependent on the hippocampus. Multiple other brain structures and circuits have vital roles in this function and (2) measurements of hippocampal volume and SFSS, for each individual, were determined at different intervals, which would make it difficult to detect a significant correlation.

Although the direct consequences of val66met substitution on BDNF levels remain to be clarified, there are a number of studies that suggest molecular mechanisms by which it could lead to a more severe decline in executive function and reduced hippocampal volume. Postmortem examination of the parietal cortex of AD patients has shown >70% decrease in BDNF mRNA55 and 40% decrease in pro-BDNF levels.56

The role of met alleles on cognition in AD has been controversial. It has been reported that the frequency of A alleles (met) in a Japanese AD population was lower than that of controls by 5%.57 In the Mainland Chinese Han population, although a similar frequency of A alleles was found among AD and controls, they reported a higher frequency of A alleles in ApoE4 female carriers with AD.58 However, multiple studies have failed to find higher frequency of A alleles in AD.59, 60, 61, 62 These controversial results might be explained by additional polymorphism(s) that may have a role in the occurrence of AD. One example is the C270T polymorphism in the non-coding area of the BDNF gene, which has been linked to a higher risk of AD in a Japanese population.63 In addition, the presence of several polymorphisms might have synergic effects on the occurrence of cognitive dysfunction. As mentioned above, Bian et al.58 found a higher frequency of val66met substitution in AD patients only in female ApoE4 carriers subgroup.

Our finding of the relationship between decline in skilled task function and val66met polymorphism may have important implications for intervention. BDNF has a major role in activity-dependent plasticity in the hippocampus.64, 65 Indeed, BDNF null mice show pronounced synaptic fatigue in CA1 synapses during high-frequency stimulation, reduced number of docked vesicles and decline in synaptic markers in this area.66 Accordingly, BDNF gene delivery has been shown to reverse neuronal atrophy and cognitive deficits in aged primates and rodent models of AD.67 Furthermore, BDNF knockout mice show decreased serotonergic axonal terminals, reduced levels of 5-HT and its metabolite (5-HIAA) in the hippocampus68 and increased depression-like behaviors.69 As val66met polymorphism leads to decreased levels of activity-dependent BDNF release,45 strategies to therapeutically increase BDNF levels including gene therapy and/or the use of small molecules binding to NTRK2 receptors70 might have successful outcome in treating depression and its associated cognitive deficits than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) that would target one particular system. There is already evidence that different anti-depressive therapies including antidepressants,71 electroconvulsive therapy72 and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation73 have all shown to increase BDNF levels in animal models of depression. Thus, there is the possibility that further research in therapeutics might lead to better treatments for cognitive and affective disorders.

There are a number of limitations to this study. First, for quantification of skilled task performance and decline in SFSS, we followed the participants for three consecutive annual visits. There is no doubt that much longer follow-ups and bigger samples size are required to better define the trend and confirm the link with val66met polymorphism. Second, only about a third of individuals enrolled in this study had neuroimaging for hippocampal volume alterations. Similar to the first point, larger sample size and measurement in multiple consecutive annual visits are required to confirm our findings. Having a larger group would help us to better determine the role of other factors such as gender, ethnicity, presence of other polymorphisms and expertise on the effects of val66met substitution on both cognition and brain structural changes that may impact SFSS.

Testing executive function in this study was performed using a flight simulator. Although the result of this study might have some implication for performance in pilots, it may also reflect age-dependent alterations in executive functions in the general public performing any skilled tasks that involve working with complex machinery. Thus, we anticipate the need of a larger longitudinal study using additional means of simulations.

In conclusion, we found that the val66met substitution was able to predict the rate of regression in SFSS and may be considered as a tool to evaluate the longitudinal decline in cognitive functioning of healthy individuals. Furthermore, it seems to modify the nature of the relationship between age and hippocampal volume. Careful genetic and neurochemical studies of BDNF may eventually lead to therapeutic interventions of benefit to older adults with cognitive and affective disorders.

References

Chao MV . Trophic factors: an evolutionary cul-de-sac or door into higher neuronal function? J Neurosci Res 2000; 59: 353–355.

Gotz R, Raulf F, Schartl M . Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is more highly conserved in structure and function than nerve growth factor during vertebrate evolution. J Neurochem 1992; 59: 432–442.

Reichardt LF . Neurotrophin-regulated signalling pathways. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2006; 361: 1545–1564.

Zhang X, Poo MM . Localized synaptic potentiation by BDNF requires local protein synthesis in the developing axon. Neuron 2002; 36: 675–688.

Nakata H, Nakamura S . Brain-derived neurotrophic factor regulates AMPA receptor trafficking to post-synaptic densities via IP3R and TRPC calcium signaling. FEBS Lett 2007; 581: 2047–2054.

Pringle AK, Sundstrom LE, Wilde GJ, Williams LR, Iannotti F . Brain-derived neurotrophic factor, but not neurotrophin-3, prevents ischaemia-induced neuronal cell death in organotypic rat hippocampal slice cultures. Neurosci Lett 1996; 211: 203–206.

Korte M, Carroll P, Wolf E, Brem G, Thoenen H, Bonhoeffer T . Hippocampal long-term potentiation is impaired in mice lacking brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995; 92: 8856–8860.

Peng S, Garzon DJ, Marchese M, Klein W, Ginsberg SD, Francis BM et al. Decreased brain-derived neurotrophic factor depends on amyloid aggregation state in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci 2009; 29: 9321–9329.

Hwang JP, Tsai SJ, Hong CJ, Yang CH, Lirng JF, Yang YM . The Val66Met polymorphism of the brain-derived neurotrophic-factor gene is associated with geriatric depression. Neurobiol Aging 2006; 27: 1834–1837.

Goodyer IM, Croudace T, Dudbridge F, Ban M, Herbert J . Polymorphisms in BDNF (Val66Met) and 5-HTTLPR, morning cortisol and subsequent depression in at-risk adolescents. Br J Psychiatry 2010; 197: 365–371.

Borroni B, Archetti S, Costanzi C, Grassi M, Ferrari M, Radeghieri A et al. Role of BDNF Val66Met functional polymorphism in Alzheimer's disease-related depression. Neurobiol Aging 2009; 30: 1406–1412.

Kim JM, Stewart R, Kim SW, Yang SJ, Shin IS, Kim YH et al. BDNF genotype potentially modifying the association between incident stroke and depression. Neurobiol Aging 2008; 29: 789–792.

Ribases M, Gratacos M, Armengol L, de Cid R, Badia A, Jimenez L et al. Met66 in the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) precursor is associated with anorexia nervosa restrictive type. Mol Psychiatry 2003; 8: 745–751.

Chen ZY, Jing D, Bath KG, Ieraci A, Khan T, Siao CJ et al. Genetic variant BDNF (Val66Met) polymorphism alters anxiety-related behavior. Science 2006; 314: 140–143.

Hosang GM, Uher R, Keers R, Cohen-Woods S, Craig I, Korszun A et al. Stressful life events and the brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 2010; 125: 345–349.

Sarchiapone M, Carli V, Roy A, Iacoviello L, Cuomo C, Latella MC et al. Association of polymorphism (Val66Met) of brain-derived neurotrophic factor with suicide attempts in depressed patients. Neuropsychobiology 2008; 57: 139–145.

Gratacos M, Gonzalez JR, Mercader JM, de Cid R, Urretavizcaya M, Estivill X . Brain-derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met and psychiatric disorders: meta-analysis of case-control studies confirm association to substance-related disorders, eating disorders, and schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2007; 61: 911–922.

Terracciano A, Martin B, Ansari D, Tanaka T, Ferrucci L, Maudsley S et al. Plasma BDNF concentration, Val66Met genetic variant and depression-related personality traits. Genes Brain Behav 2010; 9: 512–518.

Shimizu E, Hashimoto K, Iyo M . Ethnic difference of the BDNF 196G/A (val66met) polymorphism frequencies: the possibility to explain ethnic mental traits. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2004; 126B: 122–123.

Petryshen TL, Sabeti PC, Aldinger KA, Fry B, Fan JB, Schaffner SF et al. Population genetic study of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene. Mol Psychiatry 2010; 15: 810–815.

Chen ZY, Ieraci A, Teng H, Dall H, Meng CX, Herrera DG et al. Sortilin controls intracellular sorting of brain-derived neurotrophic factor to the regulated secretory pathway. J Neurosci 2005; 25: 6156–6166.

Horch HW . Local effects of BDNF on dendritic growth. Rev Neurosci 2004; 15: 117–129.

An JJ, Gharami K, Liao GY, Woo NH, Lau AG, Vanevski F et al. Distinct role of long 3′ UTR BDNF mRNA in spine morphology and synaptic plasticity in hippocampal neurons. Cell 2008; 134: 175–187.

Chiaruttini C, Vicario A, Li Z, Baj G, Braiuca P, Wu Y et al. Dendritic trafficking of BDNF mRNA is mediated by translin and blocked by the G196A (Val66Met) mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106: 16481–16486.

Hashimoto K . Brain-derived neurotrophic factor as a biomarker for mood disorders: an historical overview and future directions. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2010; 64: 341–357.

Hajek T, Kopecek M, Höschl C . Reduced hippocampal volumes in healthy carriers of brain-derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met polymorphism: meta-analysis. World J Biol Psychiatry 2011; advance online publication 4 July 2011 (e-pub ahead of print).

Cathomas F, Vogler C, Euler-Sigmund JC, de Quervain DJ, Papassotiropoulos A . Fine-mapping of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene supports an association of the Val66Met polymorphism with episodic memory. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2010; 13: 975–980.

Chen L, Lawlor DA, Lewis SJ, Yuan W, Abdollahi MR, Timpson NJ et al. Genetic association study of BDNF in depression: finding from two cohort studies and a meta-analysis. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2008; 147B: 814–821.

Yesavage JA, Taylor JL, Mumenthaler MS, Noda A, O’Hara R . Relationship of age and simulated flight performance. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999; 47: 819–823.

Taylor JL, O’Hara R, Mumenthaler MS, Yesavage JA . Relationship of CogScreen-AE to flight simulator performance and pilot age. Aviat Space Environ Med 2000; 71: 373–380.

Taylor JL, Kennedy Q, Noda A, Yesavage JA . Pilot age and expertise predict flight simulator performance: a 3-year longitudinal study. Neurology 2007; 68: 648–654.

Kay GG . CogScreen Aeromedical Edition Professional Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc: Odessa, FL, 1995.

Yesavage JA, Mumenthaler MS, Taylor JL, Friedman L, O’Hara R, Sheikh J et al. Donepezil and flight simulator performance: effects on retention of complex skills. Neurology 2002; 59: 123–125.

Shen R, Fan JB, Campbell D, Chang W, Chen J, Doucet D et al. High-throughput SNP genotyping on universal bead arrays. Mutat Res 2005; 573: 70–82.

Yesavage JA, Friedman L, Kraemer H, Tinklenberg JR, Salehi A, Noda A et al. Sleep/wake disruption in Alzheimer's disease: APOE status and longitudinal course. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2004; 17: 20–24.

Hsu YY, Schuff N, Du AT, Mark K, Zhu X, Hardin D et al. Comparison of automated and manual MRI volumetry of hippocampus in normal aging and dementia. J Magn Reson Imaging 2002; 16: 305–310.

Christensen GE, Joshi SC, Miller MI . Volumetric transformation of brain anatomy. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 1997; 16: 864–877.

Chupin M, Gerardin E, Cuingnet R, Boutet C, Lemieux L, Lehericy S et al. Fully automatic hippocampus segmentation and classification in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment applied on data from ADNI. Hippocampus 2009; 19: 579–587.

Schuff N, Woerner N, Boreta L, Kornfield T, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ et al. MRI of hippocampal volume loss in early Alzheimer's disease in relation to ApoE genotype and biomarkers. Brain 2009; 132 (Pt 4): 1067–1077.

Du AT, Schuff N, Chao LL, Kornak J, Jagust WJ, Kramer JH et al. Age effects on atrophy rates of entorhinal cortex and hippocampus. Neurobiol Aging 2006; 27: 733–740.

Adamson MM, Landy KM, Duong S, Fox-Bosetti S, Ashford JW, Murphy GM et al. Apolipoprotein E epsilon4 influences on episodic recall and brain structures in aging pilots. Neurobiol Aging 2010; 31: 1059–1063.

Csernansky JG, Joshi S, Wang L, Haller JW, Gado M, Miller JP et al. Hippocampal morphometry in schizophrenia by high dimensional brain mapping. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998; 95: 11406–11411.

Karnik MS, Wang L, Barch DM, Morris JC, Csernansky JG . BDNF polymorphism rs6265 and hippocampal structure and memory performance in healthy control subjects. Psychiatry Res 2010; 178: 425–429.

Bigler ED, Blatter DD, Anderson CV, Johnson SC, Gale SD, Hopkins RO et al. Hippocampal volume in normal aging and traumatic brain injury. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1997; 18: 11–23.

Egan MF, Kojima M, Callicott JH, Goldberg TE, Kolachana BS, Bertolino A et al. The BDNF val66met polymorphism affects activity-dependent secretion of BDNF and human memory and hippocampal function. Cell 2003; 112: 257–269.

Moffett JR, Ross B, Arun P, Madhavarao CN, Namboodiri AM . N-Acetylaspartate in the CNS: from neurodiagnostics to neurobiology. Prog Neurobiol 2007; 81: 89–131.

Stern AJ, Savostyanova AA, Goldman A, Barnett AS, van der Veen JW, Callicott JH et al. Impact of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met polymorphism on levels of hippocampal N-acetyl-aspartate assessed by magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging at 3 Tesla. Biol Psychiatry 2008; 64: 856–862.

Pezawas L, Verchinski BA, Mattay VS, Callicott JH, Kolachana BS, Straub RE et al. The brain-derived neurotrophic factor val66met polymorphism and variation in human cortical morphology. J Neurosci 2004; 24: 10099–10102.

Szeszko PR, Lipsky R, Mentschel C, Robinson D, Gunduz-Bruce H, Sevy S et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor val66met polymorphism and volume of the hippocampal formation. Mol Psychiatry 2005; 10: 631–636.

Bueller JA, Aftab M, Sen S, Gomez-Hassan D, Burmeister M, Zubieta JK . BDNF Val66Met allele is associated with reduced hippocampal volume in healthy subjects. Biol Psychiatry 2006; 59: 812–815.

Nemoto K, Ohnishi T, Mori T, Moriguchi Y, Hashimoto R, Asada T et al. The Val66Met polymorphism of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene affects age-related brain morphology. Neurosci Lett 2006; 397: 25–29.

Frodl T, Schule C, Schmitt G, Born C, Baghai T, Zill P et al. Association of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met polymorphism with reduced hippocampal volumes in major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007; 64: 410–416.

Sublette ME, Baca-Garcia E, Parsey RV, Oquendo MA, Rodrigues SM, Galfalvy H et al. Effect of BDNF val66met polymorphism on age-related amygdala volume changes in healthy subjects. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2008; 32: 1652–1655.

Dempster E, Toulopoulou T, McDonald C, Bramon E, Walshe M, Filbey F et al. Association between BDNF val66 met genotype and episodic memory. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2005; 134B: 73–75.

Holsinger RM, Schnarr J, Henry P, Castelo VT, Fahnestock M . Quantitation of BDNF mRNA in human parietal cortex by competitive reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction: decreased levels in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 2000; 76: 347–354.

Michalski B, Fahnestock M . Pro-brain-derived neurotrophic factor is decreased in parietal cortex in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 2003; 111: 148–154.

Matsushita S, Arai H, Matsui T, Yuzuriha T, Urakami K, Masaki T et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene polymorphisms and Alzheimer's disease. J Neural Transm 2005; 112: 703–711.

Bian JT, Zhang JW, Zhang ZX, Zhao HL . Association analysis of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene 196 A/G polymorphism with Alzheimer's disease (AD) in mainland Chinese. Neurosci Lett 2005; 387: 11–16.

Bagnoli S, Nacmias B, Tedde A, Guarnieri BM, Cellini E, Petruzzi C et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor genetic variants are not susceptibility factors to Alzheimer's disease in Italy. Ann Neurol 2004; 55: 447–448.

Forero DA, Benitez B, Arboleda G, Yunis JJ, Pardo R, Arboleda H . Analysis of functional polymorphisms in three synaptic plasticity-related genes (BDNF, COMT AND UCHL1) in Alzheimer's disease in Colombia. Neurosci Res 2006; 55: 334–341.

He XM, Zhang ZX, Zhang JW, Zhou YT, Tang MN, Wu CB et al. Lack of association between the BDNF gene Val66Met polymorphism and Alzheimer disease in a Chinese Han population. Neuropsychobiology 2007; 55: 151–155.

Combarros O, Infante J, Llorca J, Berciano J . Polymorphism at codon 66 of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene is not associated with sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2004; 18: 55–58.

Kunugi H, Ueki A, Otsuka M, Isse K, Hirasawa H, Kato N et al. A novel polymorphism of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene associated with late-onset Alzheimer's disease. Mol Psychiatry 2001; 6: 83–86.

Arancio O, Chao MV . Neurotrophins, synaptic plasticity and dementia. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2007; 17: 325–330.

Fritsch B, Reis J, Martinowich K, Schambra HM, Ji Y, Cohen LG et al. Direct current stimulation promotes BDNF-dependent synaptic plasticity: potential implications for motor learning. Neuron 2010; 66: 198–204.

Gottschalk WA, Jiang H, Tartaglia N, Feng L, Figurov A, Lu B . Signaling mechanisms mediating BDNF modulation of synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. Learn Mem 1999; 6: 243–256.

Nagahara AH, Merrill DA, Coppola G, Tsukada S, Schroeder BE, Shaked GM et al. Neuroprotective effects of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in rodent and primate models of Alzheimer's disease. Nat Med 2009; 15: 331–337.

Lyons L, Elbeltagy M, Umka J, Markwick R, Startin C, Bennett G et al. Fluoxetine reverses the memory impairment and reduction in proliferation and survival of hippocampal cells caused by methotrexate chemotherapy. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011; 215: 105–115.

Monteggia LM . Elucidating the role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the brain. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164: 1790.

Massa SM, Yang T, Xie Y, Shi J, Bilgen M, Joyce JN et al. Small molecule BDNF mimetics activate TrkB signaling and prevent neuronal degeneration in rodents. J Clin Invest 2010; 120: 1774–1785.

Russo-Neustadt A, Beard RC, Cotman CW . Exercise, antidepressant medications, and enhanced brain derived neurotrophic factor expression. Neuropsychopharmacology 1999; 21: 679–682.

Kim J, Gale K, Kondratyev A . Effects of repeated minimal electroshock seizures on NGF, BDNF and FGF-2 protein in the rat brain during postnatal development. Int J Dev Neurosci 2010; 28: 227–232.

Muller MB, Toschi N, Kresse AE, Post A, Keck ME . Long-term repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation increases the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and cholecystokinin mRNA, but not neuropeptide tyrosine mRNA in specific areas of rat brain. Neuropsychopharmacology 2000; 23: 205–215.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs’ War Related Illness and Injury Study Center (WRIISC), the Sierra-Pacific VA Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment and Medical Research Service, NIA grants R37 AG12713, P30 AG17824, R01AG021632 andP41 RR023953. These sponsors solely provided financial support or facilities to conduct the study. We are very grateful to Mrs Persia Salehi for her professional graphic work (Figure 1) and to Dr Margaret Fahnestock, McMaster University, Canada, for the critical reading of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Sanchez, M., Das, D., Taylor, J. et al. BDNF polymorphism predicts the rate of decline in skilled task performance and hippocampal volume in healthy individuals. Transl Psychiatry 1, e51 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2011.47

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2011.47

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Genotyping of Macaque Population on the Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Gene Polymorphism by Mismatch Amplification Mutation Assay (MAMA)-PCR

Bulletin of Experimental Biology and Medicine (2023)

-

Effect of the interaction between BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and daily physical activity on mean diffusivity

Brain Imaging and Behavior (2020)

-

Genetics and Functional Imaging: Effects of APOE, BDNF, COMT, and KIBRA in Aging

Neuropsychology Review (2015)

-

Genetic polymorphisms and traumatic brain injury: the contribution of individual differences to recovery

Brain Imaging and Behavior (2014)

-

BDNF-based synaptic repair as a disease-modifying strategy for neurodegenerative diseases

Nature Reviews Neuroscience (2013)