Abstract

Traditionally, spatially-resolved photoluminescence (PL) has been performed using a point-by-point scan mode with both excitation and detection occurring at the same spatial location. But with the availability of high quality detector arrays like CCDs, an imaging mode has become popular for performing spatially-resolved PL. By illuminating the entire area of interest and collecting the data simultaneously from all spatial locations, the measurement efficiency can be greatly improved. However, this new approach has proceeded under the implicit assumption of comparable spatial resolution. We show here that when carrier diffusion is present, the spatial resolution can actually differ substantially between the two modes, with the less efficient scan mode being far superior. We apply both techniques in investigation of defects in a GaAs epilayer – where isolated singlet and doublet dislocations can be identified. A superposition principle is developed for solving the diffusion equation to extract the intrinsic carrier diffusion length, which can be applied to a system with arbitrarily distributed defects. The understanding derived from this work is significant for a broad range of problems in physics and beyond (for instance biology) – whenever the dynamics of generation, diffusion and annihilation of species can be probed with either measurement mode.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The performance of electronic and optoelectronic devices depends strongly on the nature and quantity of defects in the constituent materials. Imperfections in the crystal lattice tend to introduce localized states with energy levels lying within the forbidden gap of a semiconductor. When free carriers are injected by an electrical bias or generated by illumination, these levels augment nonradiative recombination by capturing the carriers and providing them with alternative dissipation pathways. This loss competes with desired outcomes, like radiative recombination to produce light in a light-emitting diode or extraction via electronic drift to produce current in a solar cell. More generally, defects lead to two important consequences for optoelectronic device operation: (1) they enhance the recombination of electron-hole pairs which decreases the carrier lifetime; and (2) they increase leakage current which can amplify device noise1.

Spatially-resolved optical spectroscopy is widely used for the characterization of individual defects2,3. One apparent limitation to the spatial resolution is optical diffraction4, although resolution beyond the diffraction limit is possible with near-field and other special techniques2,5,6,7,8,9. This work addresses how another effect – carrier diffusion, which exists in virtually all real-world devices – can dramatically impact the spatial resolution under different excitation/detection modes. Carrier diffusion is the mechanism that allows individual microscopic defects to collectively yield a range of important mesoscopic effects. Therefore, on the one hand, understanding the effect of an individual defect is critically important for interpreting mesoscopic behavior; and on the other hand, an individual defect can be used as a sensor for probing mesoscopic phenomena, for instance carrier diffusion and predicting the “intrinsic” diffusion length in the absence of defects10.

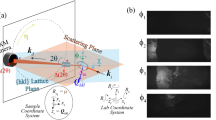

Photoluminescence (PL), cathodoluminescence (CL) and laser-beam or electron-beam induced current (LBIC or EBIC) microscopy are powerful techniques for studying carrier transport and recombination in the vicinity of extended defects like dislocations. Generally speaking, according to differences in the manner of excitation and collection, the commonly known spatially-resolved techniques can be divided into three categories: (1) Uniform illumination/Local detection (U/L mode): the sample is illuminated by a large excitation beam and the emission is detected in a spatially-resolved manner, usually via imaging with a CCD camera or mapping point-by-point. In this case, despite the difference in data collection efficiency, the imaging and mapping methods yield about the same spatial resolution. (2) Local excitation/Local detection (L/L mode): by using a confocal optical technique, when the excitation and collection apertures are aligned, the collected signal originates only from the excitation site. PL mapping can be performed in either U/L or L/L mode. (3) Local excitation/Global collection (L/G mode): for example CL, where the electron beam initially produces a highly localized carrier population, but the carriers are free to diffuse before recombining to yield luminescence. Here, a non-confocal method is usually used for signal collection, to include the contribution from carriers that have diffused away from the excitation site. In a diffusion free system, the spatial resolution is determined by the point-spread function of the focused excitation beam and the spatial resolutions are expected to be more or less the same for all the three modes. However, with diffusion, roughly speaking, the spatial resolution in the U/L and L/G modes is determined by the beam size or diffusion length, whichever is larger. Therefore, for a material with a large diffusion length (i.e. a material of high quality), the spatial resolution is significantly degraded by carrier diffusion. In such a situation, the L/L mode can offer substantially better spatial resolution without changing the beam size or collection optics, based on a simple mathematical consideration that has not been generally appreciated.

The dynamics of carriers in a semiconductor is typically governed by a diffusion equation that contains generation, diffusion and annihilation (recombination) terms1. Similar differential equations are used for many other systems, such as thermal diffusion11 and molecular diffusion in biology12. To describe the local concentration inhomogeneity centered on an isolated defect (r = 0), one normally defines a so-called contrast function

where I0 is the signal from the homogeneous area (in our case the defect-free area) and I(r) is the signal at position r. In the literature, most of the contrast function calculations are performed for CL or EBIC with unique defect geometries, which often results in rather complicated functional forms for C(r)13,14,15,16. However, the basic component of C(r) is always exp(-r/Ld) with Ld being the effective diffusion length, i.e. the carrier depletion near the defect is assumed to decrease exponentially with distance from the defect. This functional form has been used and indeed nearly taken for granted, in all three of the above mentioned excitation/detection modes10,17,18.

In this report, for the first time, we compare the spatial resolution of the U/L and L/L modes directly, by performing PL mapping on an isolated single defect and on a defect pair in each mode. Our results provide unambiguous experimental proof of the superior spatial resolution achievable with the L/L mode relative to the U/L mode, as supported by our mathematical considerations.

Results

A. One-dimensional (1-D) problem

We first consider the L/L mode by starting with a 1-D model. In steady state, the excess carrier density in the semiconductor is governed by the following 1-D continuity equation:

where n(x) represents the carrier density, D is the carrier diffusivity, τ the carrier lifetime or 1/τ the recombination rate, G the generation rate with the assumption that the excitation profile is a delta function and the diffusion length is defined as  . Assuming that the excitation is at x = 0 and an isolated defect at x0 > 0 has an infinite recombination rate, we have these boundary conditions: n(x0) = 0 and n(±∞) = 0, with x0 being the separation between the defect and excitation/detection site. The solution of Eq. (2) satisfying these boundary conditions is:

. Assuming that the excitation is at x = 0 and an isolated defect at x0 > 0 has an infinite recombination rate, we have these boundary conditions: n(x0) = 0 and n(±∞) = 0, with x0 being the separation between the defect and excitation/detection site. The solution of Eq. (2) satisfying these boundary conditions is:

Note that letting x0 → ∞ leads to the solution for the defect-free case, i.e. n0exp(-|x|/Ld) with n0 = Gτ/(2Ld). The contrast function can be calculated using the definition C(x0) = [n0-n(0,x0)]/n0, which describes the relative reduction of the carrier density at the excitation and detection site x = 0. Explicitly,

Surprisingly, the slope of - lnC(x0) vs. x0 is 2/Ld, a factor of 2 larger than one might initially suspect, which means that the extracted diffusion length would be a factor of 2 smaller than the actual value if assuming C(x0) ∝ exp(-x0/Ld).

Although the above 1-D problem has been solved analytically as described above, we introduce an alternative method using a superposition principle to solve the same problem because it will be very useful for the more challenging 2-D case. We note that when the recombination rate at the defect site is much larger than at a general site, the defect can be simulated as an additional negative generation at x0 with a generation rate of GD = - G exp(-x0/Ld). The superposition of the two excitations, G at x = 0 and GD at x = x0, yields the exact same solution as Eq. (3).

For the U/L mode, the steady-state solution is simply n = gτ in the absence of defects, where g is the generation rate per unit length. Adding a defect is equivalent to introducing a negative generation – Gδ(x), with G = 2gLd at the defect site x = 0. The combined solution is then gτ[1-exp(-|x|/Ld)], which yields n(0) = 0 and C(x) = exp(-x/Ld), the well-known form. Clearly, the contrast functions are different for the two excitation/detection modes. The results imply that the effects of a defect should be much more localized in the L/L mode, providing substantially better spatial resolution for resolving nearby defects.

B. 2-D problem without defect

A 2-D model is appropriate for a relatively thin layer that has nearly uniform carrier density along the perpendicular direction. The excitation site is selected at the origin r = 0. The diffusion equation in cylindrical coordinates is given as

where  is the 2-D delta function. The solution of Eq. (5) is a modified Bessel function K0(ξ) with ξ = r/Ld. If we apply the boundary conditions n(∞) = 0 and

is the 2-D delta function. The solution of Eq. (5) is a modified Bessel function K0(ξ) with ξ = r/Ld. If we apply the boundary conditions n(∞) = 0 and  with r0 → 0, the solution will be

with r0 → 0, the solution will be

Though K0(ξ) diverges at ξ = 0, ξK0(ξ) is integrable near ξ = 0. We can replace K0(0) with the average of K0(ξ) over a small circle of radius ε:19

which is equivalent to the effect of having a finite experimental probe. For example, in the PL measurement ε could be related to the diffraction limit spot size.

C. Superposition principle in 2-D with defect

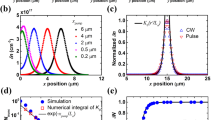

Now we use the superposition principle to derive the carrier distribution in the vicinity of a defect. First the L/L mode is considered with the configuration shown schematically in Fig. 1.

Suppose that, in an infinitely large plane without defects, the carrier density generated by a laser beam at r = 0 is n0. At a distance r0 away, the density will reduce to ηn0, where η is a decay function that depends on the distance r0but is independent of the density at r = 0, varying in the range of 0 ≤ η ≤ 1. If a defect with an infinite recombination rate is placed at r0, a negative generation source yielding a density –ηn0 is needed to ensure that the density at the defect site remains zero. Now using the superposition principle, the net carrier density at r = 0 is the superposition of the contributions from the incident light at r = 0 and the negative generation source at r0, which totals n0-η2n0.

According to the definition of the contrast function, we have

Thus we can conclude that the contrast function C in the 2-D case is also the square of the decay function η. Applying the analytic solution from Part (B), the decay function η is equal to  , and

, and

We note that although  is finite, its magnitude depends on the specific value of ε used in Eq. (7). In principle, an appropriate value of ε can be selected based on the excitation beam size to give a meaningful value of

is finite, its magnitude depends on the specific value of ε used in Eq. (7). In principle, an appropriate value of ε can be selected based on the excitation beam size to give a meaningful value of  . In practice, this is rather inconvenient and also not necessary. Because the technique is most useful when the excitation beam size is significantly smaller than the diffusion length, skipping the r = 0 point will not have any major impact on the accuracy of the derived diffusion length and

. In practice, this is rather inconvenient and also not necessary. Because the technique is most useful when the excitation beam size is significantly smaller than the diffusion length, skipping the r = 0 point will not have any major impact on the accuracy of the derived diffusion length and  in Eq. (8) can be treated as a pre-factor in the fitting.

in Eq. (8) can be treated as a pre-factor in the fitting.

For the U/L mode, the steady-state solution is similar to that in the 1-D case. We assume n = gτ in the absence of defects. Near the defect at r0 = 0, the effect of the defect can be described by a negative generation as -GD/(2πD)K0(r/Ld), where -GD represents the effective generation rate of the defect. As in the 1-D case, a defect is assumed to have an infinite recombination rate at the defect site and zero lateral extension, so we have

Then the carrier density is  20 and the contrast function is

20 and the contrast function is

Again in fitting the experimental data, the r = 0 point can be skipped and  can be treated as a pre-factor.

can be treated as a pre-factor.

We note that these results are similar to what we obtained in the 1-D case, where the contrast function is η = exp(-x0/Ld) for the U/L mode and η2 = exp(–2x0/Ld) for the L/L mode. Therefore, in an ideal situation, if two defects separated by δx0 are resolvable by a detection system operated in the U/L mode, then they can be resolved equally well when the separation is reduced to δx0/2 by the same detection system operated in the L/L mode.

D. Experimental comparison of the two excitation/detection modes

We have shown previously, using PL mapping with either the L/L or U/L mode10,21, that the effect of one isolated extended defect (e.g., a dislocation) manifests as a circular dark region with emission intensity that increases with distance from the defect, asymptotically approaching that of the defect free region. Here we first illustrate how the impact range of the same isolated defect may appear very different under the two modes, as shown in Fig. 2a–2c for the three excitation densities under the L/L mode and Fig. 2d for one example of the U/L mode. Figure 3a–3b depict the circularly averaged radial contrast functions computed using Eq. (1) for all of the data taken under the two different modes. Although within the L/L mode the size of the dark region varies visibly with the excitation density as a result of the competition between point defects (un-resolvable in this type of measurement) and the extended defect10, the impact range of the defect under the U/L mode is clearly much larger than what is observed in the L/L mode. If one simply modeled the data using the common contrast function C(r) ~ exp(-r/L), one would deduce an effective diffusion length from the L/L data that is approximately half the actual diffusion length obtained from the U/L data. However, when the contrast functions defined in Eq. (8) and Eq. (9) are used for the L/L and U/L modes respectively, the diffusion lengths are generally found to be consistent across all measurements, accurately reflecting the intrinsic material property of the same region. The fitting results for the diffusion length are shown in Fig. 3c. The variation within each mode is due to a range of other subtle effects, which have been discussed elsewhere10,21. The results suggest that the carrier diffusion length can vary approximately from 6 to 20 μm in this particular region of the sample with varying excitation density. These values are typical for high quality GaAs epilayers22. More importantly, the faster decay of the contrast function under the L/L mode suggests that substantially better spatial resolution can be achieved in the L/L mode when compared with the U/L mode.

Circularly averaged radial contrast functions deduced from the PL mapping data, shown as symbols in (a) for the L/L mode and (b) for the U/L mode. Solid lines are theoretical fits using Eq. (8) and Eq. (9), respectively, for the L/L and U/L modes. (c) Fitting results of diffusion lengths for the L/L mode and U/L mode on a single defect. The points represent the best fits, the error bars give the variation ranges that are able to offer reasonably good fits.

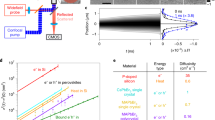

Next we demonstrate that the L/L mode can indeed yield much better spatial resolution when attempting to resolve nearby defects. For this purpose, we use a pair of dislocations separated by a distance (~ 15 μm) that is slightly larger than or about one half of the diffusion length, depending on the excitation condition. Selected PL mapping results for the doublet are shown in Fig. 4 for the two modes, with the corresponding contrast functions given in Fig. 5. The doublet is clearly resolved in the L/L mode, as shown in the PL maps Fig. 4a–4c and contrast functions Fig. 5a. The resolution is particularly good at low excitation intensity where the diminished carrier density leads to a reduction in the diffusion length10. For comparison, the doublet is barely resolved in the U/L mode PL map shown in Fig. 4d. This shortcoming is also evident in the contrast functions for the U/L mode data shown in Fig. 5b. Except for the loss of circular symmetry, the results for the doublet are qualitatively similar to those of the singlet. For instance, the influence range of the defect varies with excitation density in a similar fashion for the L/L mode. The contrast functions shown in Fig. 5a–5b are slightly asymmetric, which might be due to a real material difference, but since the asymmetry is more apparent for the weaker signal, it may also be attributed to noise. We have performed the same fitting analysis that was used for the singlet on each side of the doublet, yielding averaged diffusion lengths shown in Fig. 5c. The trends are qualitatively the same as those shown in Fig. 3c, except that the deduced diffusion lengths are somewhat larger overall. This variation is understandable because the recombination dynamics can depend sensitively on the density of microscopic defects that may vary across a large wafer10. Quantitatively, the ratio γ = C(rd)/C(0) can be used to measure the improvement in resolution, where C(rd) and C(0) are respectively the contrast function values at the defect sites (averaged) and the center of the line connecting them. For data taken in the two different modes but having comparable diffusion lengths Ld ≈ 12–13 μm (e.g., Fig. 4c and Fig. 4d), we get γL/L ≈ 1.64–3.05 and γU/L ≈ 1.08. Altogether, the results unambiguously confirm the prediction that the L/L mode can offer vastly superior spatial resolution when the mechanism of diffusion is important.

Contrast functions computed from the PL mapping data of the doublet along the line of symmetry passing through the two defects (a) for the L/L mode and (b) for the U/L mode. The solid lines are guides to the eye. (c) Diffusion lengths derived from fits to the L/L mode and U/L mode contrast profiles for the defect pair.

Discussion

We have demonstrated both theoretically and experimentally that two generation/detection modes – (local generation)/(local detection) and (uniform generation)/(local detection) – can yield very different spatial resolution when species diffusion is present. The first mode, which is referred to as L/L mode, is shown to have far superior spatial resolution compared to the second (U/L) mode. The improvement in spatial resolution, approximately a factor of 2, can be attributed to a steeper contrast function, approximately exp(-2x/Ld) vs. exp(-x/Ld), when the nominal diffusion length is Ld. The theoretical prediction has been proved unambiguously with PL mapping data and analysis on single and doublet defects in GaAs. We conclude that, even though the U/L mode has superior collection efficiency, it comes at the expense of reduced spatial resolution when species diffusion is significant. In light of the fact that both modes are widely used for studying spatial inhomogeneity and diffusion in a wide variety of natural systems (e.g., electrons in a semiconductor, thermal transport in a construction material, or molecular diffusion in a biological cell), the principle derived in this work should garner broad interest and impact scientific disciplines well beyond the field of semiconductors.

Methods

We used a quasi-two dimensional system – namely, a double heterostructure of GaInP/GaAs/GaInP, in which the photo-generated carriers are confined within the thin GaAs layer between GaInP barriers such that the GaAs interfaces are passivated to eliminate interface recombination10. The sample was grown by metal-organic vapor phase epitaxy (MOVPE) on a semi-insulating GaAs substrate and has a very low as-grown threading dislocation density on the order of 103 cm−2. All experiments were conducted at room temperature on a Horiba LabRAM HR800 confocal Raman microscope. For the L/L mode, a 633 nm laser was used with a 100x microscope lens (NA = 0.9) that can produce an excitation spot size with a diameter of about 860 nm. The PL signal was focused to the confocal aperture, dispersed by a spectrometer and detected by a CCD array. For the U/L mode, we used an 808 nm laser coupled through the white-light illumination port of the microscope with a Kohler optics system that can generate uniform illumination under the same microscope lens. The PL signal was collected in two ways: (1) mapping as in the L/L mode or (2) imaging using the microscope camera. The two collection methods yielded more or less the same results, although the signal-to-noise ratio of the latter method, in line with the commonly adopted more efficient way of taking data3,21, was not as good. A better camera would presumably alleviate this deficiency. We used the same data collection method for comparing the L/L and U/L modes to ensure that the only difference between the experiments was the excitation beam shape (i.e., δ-function-like vs. uniform).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Chen, F. et al. Spatial resolution versus data acquisition efficiency in mapping an inhomogeneous system with species diffusion. Sci. Rep. 5, 10542; doi: 10.1038/srep10542 (2015).

References

Sze, S. M. & Ng, K. K. Physics of Semiconductor Devices. John Wiley & Sons, (2006).

Bao, W. et al. Mapping local charge recombination heterogeneity by multidimensional nanospectroscopic imaging. Science 338, 1317–1321 (2012).

Alberi, K. et al. Measuring long-range carrier diffusion across multiple grains in polycrystalline semiconductors by photoluminescence imaging. Nat. Commu. 4, 2699 1-7 (2013).

Abbe, E. Beiträge zur Theorie des Mikroskops und der mikroskopischen Wahrnehmung. Archiv für Mikroskopische Anatomie 9, 413–468 (1873).

Fang, N., Lee, H., Sun, C. & Zhang, X. Sub–diffraction-limited optical imaging with a silver superlens. Science 308, 534–537 (2005).

Moerner, W. E. & Kador, L. Optical detection and spectroscopy of single molecules in a solid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 62, 2535–2538 (1989).

Moerner, W. E. & Fromm. D. P. Methods of single-molecule fluorescence spectroscopy and microscopy. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 74, 3597–3619 (2003).

Hell, S. W. & Wichmann, J. Breaking the diffraction resolution limit by stimulated emission: stimulated-emission-depletion fluorescence microscopy. Opt. Lett. 19, 780–782 (1994).

Betzig, E. et al. Imaging intracellular fluorescent proteins at nanometer resolution. Science 313, 1642–1645 (2006).

Gfroerer, T. H., Zhang, Yong, Wanlass, M. W. An extended defect as a sensor for free carrier diffusion in a semiconductor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 012114 (2013).

Kulish, V. V., Lage, J. L. Diffusion within a porous medium with randomly distributed heat sinks. Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer 43, 3481–3496 (2000).

Brownstein, K. R. & Tarr, C. E. Importance of classical diffusion in NMR studies of water in biological cells. Phys. Rev. A 19, 2446–2453 (1979).

Donolato, C. Contrast and resolution of SEM charge collection images of dislocations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 34, 80–81 (1979).

Donolato, C. On the theory of SEM charge-collection imaging of localized defects in semiconductors. Optik 52, 19–36 (1978/79).

Pasemann, L. A contribution to the theory of beam induced current characterization of dislocations. J. Appl. Phys. 69, 6387–6393 (1991).

Jakubowicz, A. Theory of cathodoluminescence contrast from localized defects in semiconductors. J. Appl. Phys. 59, 2205–2209 (1986).

Pauc, N., Philips M. R., Aimez, V. & Drouin, D. Carrier recombination near threading dislocations in GaN epilayers by low voltage cathodoluminescence. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 161905 (2006).

Suzuki, T. & Matsumoto, Y. Effects of dislocations on photoluminescent properties in liquid phase epitaxial GaP. Appl. Phys. Lett. 26, 431–432 (1975).

Donolato, C. Modeling the effect of dislocations on the minority carrier diffusion length of a semiconductor. J. Appl. Phys. 84, 2656–2664 (1998).

Rosner, S. J., Carr, E. C., Ludowise, M. J., Girolami, G. & Erikson, H. I. Correlation of cathodoluminescence inhomogeneity with microstructural defects in epitaxial GaN grown by metalorganic chemical-vapor deposition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 70, 420–422 (1997).

Gfroerer, T. H., Crowley, C. M., Read, C. M. & Wanlass, M. W. Excitation-dependent recombination and diffusion near an isolated dislocation in GaAs. J. Appl. Phys. 111, 093712 (2012).

Gilliland, G. D., Wolford, D. J., Kuech, T. F., Bradley, J. A. & Hjalmarson, H. P. Minority-carrier recombination kinetics and transport in “surface-free” GaAs/AlxGa1-xAs double heterostructures. J. Appl. Phys. 73, 8386–8396 (1993).

Acknowledgements

We thank support from ARO/MURI, DARPA/MTO and CRI. FXC acknowledges the support from Wuhan University of Technology for her visit at UNC-Charlotte and the support from the natural science foundation of Hubei Province (No. 2014CFB864). YZ acknowledges support of Bissell Distinguished Professorship. And the authors would like to thank J. J. Carapella for performing the MOVPE growth.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z. contributed to the design of the experiment and foundation of the theoretical model. F.X.C. and A.N.F. carried out the experimental measurements and data analysis. M.W.W. and T.H.G. designed the samples. F.X.C., Y.Z. and T.H.G. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed and commented on the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, F., Zhang, Y., Gfroerer, T. et al. Spatial resolution versus data acquisition efficiency in mapping an inhomogeneous system with species diffusion. Sci Rep 5, 10542 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep10542

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep10542

This article is cited by

-

Overcoming diffusion-related limitations in semiconductor defect imaging with phonon-plasmon-coupled mode Raman scattering

Light: Science & Applications (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.