Abstract

Methylacetoin (3-hydroxy-3-methylbutan-2-one) and 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol are currently obtained exclusively via chemical synthesis. Here, we report, to the best of our knowledge, the first alternative route, using engineered Escherichia coli. The biological synthesis of methylacetoin was first accomplished by reversing its biodegradation, which involved modifying the enzyme complex involved, switching the reaction substrate and coupling the process to an exothermic reaction. 2-Methyl-2,3-butanediol was then obtained by reducing methylacetoin by exploiting the substrate promiscuity of acetoin reductase. A complete biosynthetic pathway from renewable glucose and acetone was then established and optimized via in vivo enzyme screening and host metabolic engineering, which led to titers of 3.4 and 3.2 g l−1 for methylacetoin and 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol, respectively. This work presents a biodegradation-inspired approach to creating new biosynthetic pathways for small molecules with no available natural biosynthetic pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

For a sustainable future, researchers are attempting to increase the number of small molecules that can be produced from renewable biomass, for use as chemical building blocks or liquid fuels1. C5-branched compounds, which have unique carbon structures, are interesting targets because of their varied potential applications. For example, methylacetoin and 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol can be used to produce solvents, polymers2 and pharmaceutical products3,4. Via standard chemical dehydration, methylacetoin can be converted into methyl isopropenyl ketone, which is used to produce optical plastics, photodegradable plastics and fire-resistant rubbers. Using established technology, 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol can be dehydrated over a pyrophosphate catalyst to form a mixture of isoprene and methyl isopropyl ketone (MIPK)5. Isoprene is a monomer used in synthetic rubbers. MIPK is a better gasoline additive than methyl tert-butyl ether and can also be used as a food additive, solvent, tantalum and niobium extractant and reagent in indoline synthesis6. However, the current chemical production of these compounds suffers from limited feedstocks, the use of toxic catalysts and high costs, which limits their widespread use7,8.

Bioconversions using engineered microorganisms occur under mild conditions, have high selectivity and have low potential costs and are thus highly valued as an alternative source of chemicals and fuels. The first challenge we faced in establishing a microbial production route to methylacetoin and 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol was the lack of natural biosynthetic pathways to these compounds. Methylacetoin was detected in the secretions of Rhyssa persuasoria, Xyloterus domesticus and X. lineatus; however, the metabolic origin has not been studied9,10. 2-Methyl-2,3-butanediol was found in blood and urine samples from animals that had inhaled or ingested tert-amyl methyl ether, a common gasoline additive, likely from a monooxygenase reaction11. However, this biochemical reaction cannot be used for the microbial production of methyl-2,3-butanediol because tert-amyl methyl ether is not biologically available either. Thus, the de novo design and construction of non-natural synthetic pathways is required and to be economically competitive, an ideal biosynthetic pathway should be straightforward with high atom efficiency and a minimal number of steps that preferably involve the condensation of small molecules from the cell's central metabolism.

Here, we established two biosynthetic pathways that produce one molecule of C5 product from one acetone and one-half or one glucose molecule inspired by the idea of reversing the known methylacetoin biodegradation pathway. On the basis of thermodynamic principles and mechanistic insight, we accomplished this reversal by modifying the enzyme complex, switching the reaction substrate and coupling to an exothermic reaction to overcome thermodynamic limitations. After optimization, the strains exhibited promising productivities and yields.

Results

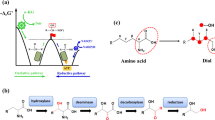

Biosynthesis of methylacetoin by reversing its biodegradation

Methylacetoin is not a natural metabolite of microorganisms. However, as an artificial substance, it can be degraded by some bacteria to serve as a carbon source for their growth12. As reported, one molecule of methylacetoin degrades to one acetone and one acetyl-CoA while generating one NADH molecule from NAD+, catalyzed by a methylacetoin/acetoin dehydrogenase complex (Fig. 1). This biodegradation has an estimated ΔrG′° of −1.7 kcal mol−1 (calculated using GCM software13, which is based on group contribution theory), which favors the forward reaction. However, previous studies have concluded that bioreactions with free energies between +3.5 kcal mol−1 and −3.5 kcal mol−1 are potentially reversible14. Thus, we proposed redirecting the reaction to achieve methylacetoin biosynthesis by elevating the acetyl-CoA and acetone concentrations. To test this hypothesis, we cloned the operon acoABCL (which encodes the methylacetoin/acetoin dehydrogenase complex) from Bacillus subtilis into E. coli and confirmed its functional expression by observing the acetoin and methylacetoin degradation activity in vivo (Supplementary Fig. S1). We expected that methylacetoin could be synthesized by the recombinant E. coli from endogenous acetyl-CoA and NAD+ and exogenous acetone, which was added to reach a 200 mM concentration. However, no methylacetoin was detected from this culture. Increasing the acetone concentration further caused cell death. Increasing the intracellular acetyl-CoA concentration 34-fold via metabolic engineering has been previously reported15 but is unlikely to increase the methylacetoin production to an acceptable level.

Biodegradation-inspired construction of the biosynthetic pathways.

Methylacetoin biodegradation is presented with a dashed line and the constructed biosynthetic pathways are presented using a solid line. The enzymes (gene names in parentheses) for each numbered step are as follows: (1) glycolysis; (2,3) acetolactate synthase and acetolactate decarboxylase (alsS and alsD); (4) acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (acoD); (5) acetoin:2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol oxidoreductase (acoAB); (6) dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase (acoC); (7) dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (acoL); (8) acetoin/methylacetoin reductase (bdhA). Enzymes (5), (6) and (7) form the degradation complex. (6) and (7) need to be deleted to block biodegradation during the biosynthesis. The presence of (4) enhanced the biosynthesis of methylacetoin from acetoin and acetone by improving the reaction thermodynamics.

We then referred back to methylacetoin biodegradation, this time with respect to the detailed enzymatic reaction mechanism. The degradation complex consists of three component enzymes: acetoin:2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol oxidoreductase (AcoAB), dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase (AcoC) and dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (AcoL). This AcoAB component is a thiamine pyrophosphate (ThDP)-dependent enzyme that cleaves the carbon-carbon bond in methylacetoin to release acetone and a ThDP-bound ‘active acetaldehyde’; AcoC oxidizes the acetaldehyde into an acetyl group and transfers it to free CoA to form acetyl-CoA via its lipoamide cofactor; AcoL regenerates the oxidized lipoamide using NAD+ and generates NADH16 (Fig. 1). In conclusion, methylacetoin degrades through a four-step reaction sequence organized by a multienzyme complex. The key step that must be reversed is the carbon-carbon bond cleavage catalyzed by AcoAB, i.e., a ThDP-bound ‘active acetaldehyde’ must condense with an acetone for methylacetoin synthesis. Because providing the ‘active acetaldehyde’ via the reduction of acetyl-CoA through AcoC and AcoL proved difficult, as described above, we reasoned that exchanging the acetyl-CoA with a higher energy substrate may enable the reversion. Our first candidate was pyruvate, the direct precursor in the central metabolism of acetyl-CoA and the end product of glycolysis. Energy calculations predicted that this substrate could greatly improve the thermodynamic aspects of the methylacetoin biosynthesis by providing an estimated ΔrG′° of −15.05 kcal mol−1, which would make the reaction irreversible. As found for other ThDP enzymes such as pyruvate decarboxylase and acetolactate synthase, the decarboxylation of pyruvate can generate an ‘active aldehyde’ that is equivalent to that found in AcoAB. Another necessary modification is to block the ‘active aldehyde’ from transferring to AcoC; otherwise, the degradative reaction will occur rather than condensation (Fig. 1). The remaining question is whether pyruvate is an acceptable substrate for AcoAB (or AcoABCL), as previous studies have obtained inconsistent results16. To test this strategy, we omitted both acoC and acoL to clone acoAB alone in E. coli BL21(DE3). In the in vitro tests, the AcoAB enzyme prepared from this strain catalyzed the generation of methylacetoin from pyruvate and acetone, which was confirmed in GC-MS by comparison to the known compound (Supplementary Fig. S2). The recombinant E. coli was then used to produce methylacetoin via shake-flask experiments. After cultivating in an M9 glucose minimal medium supplied with 200 mM acetone under air-limited conditions for 24 h, 7.1 mg l−1 of methylacetoin accumulated in the culture broth [Fig. 2, strain BL21(DE3)/pJXL32]. No methylacetoin was produced without the addition of acetone. We also examined the recombinant strains for any degradation activity. Unlike those strain expressing AcoABCL, the AcoAB strain did not degrade either methylacetoin or acetoin (Supplementary Fig. S1), which indicates that the ThDP-bound ‘active acetaldehyde’ tends to condense rather than release as free acetaldehyde, as occurred with pyruvate decarboxylase17.

Biosynthesis of methylacetoin and 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol.

(a) Plasmids carrying the pathway genes. (b) Methylacetoin and 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol production via pathway 1 or 2 hosted by BL21(DE3) or YYC202(DE3)ΔldhA. The BL21(DE3) strains and YYC202(DE3)ΔldhA strains were cultured in an M9 medium and enhanced M9 medium, respectively, under shake-flask and air-limited conditions (see Method for details). After gene expression was induced, 200 mM acetone was added. The product concentrations were determined after cultivating for 24 h by GC or GC-MS. The error bars represent the standard error associated with triplicate experiments.

To increase the productivity, we screened AcoAB enzymes from three acetoin-degrading bacteria arbitrarily selected from a pool of 22, namely, B. subtilis, Pelobacter carbinolicus (codon optimized) and Pseudomonas pudita18. The highest productivities were achieved using AcoAB from B. subtilis and were 3.1- and 1.1-fold those of the P. carbinolicus and P. pudita isozymes, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S3). We further screened other ThDP-dependent enzymes, including YerE from Yersinia pseudotuberculosis (codon optimized)19, PDC from Zymomonas mobilis and its Glu473Gln mutation17, PdhAB from B. subtilis and PdhAB from Sus scrofa (optimized for codon with the transit peptides removed). No detectable methylacetoin was produced using recombinant E. coli strains expressing these enzymes. Similarly, no or only faint activities were detected for these enzyme samples in vitro (Supplementary Fig. S4). Therefore, AcoAB from B. subtilis was used in the following studies. This biosynthetic route based on the condensation of pyruvate and acetone catalyzed by AcoAB was denoted as pathway 1. Its overall stoichiometry is as follows: 1/2 Glucose + 1 Acetone → 1 Methylacetoin + 1 CO2 + 1 ATP + 1 NADH.

Pathway 1 successfully produced methylacetoin in the recombinant E. coli culture. However, the achieved methylacetoin titer was much lower than the acetone and pyruvate concentrations, which implies that the reaction is kinetically limited because it is highly thermodynamically favorable, as discussed above. This observation is not surprising because pyruvate is not the native substrate for AcoABCL and thus has a low substrate-enzyme affinity. To address this issue, we started using acetoin instead of pyruvate as the ‘active acetaldehyde’ donor for methylacetoin synthesis and an acetaldehyde would be concomitantly generated instead of a CO2 (Fig. 1). Acetoin was reported to be degraded by AcoABCL with an activity 81% that of methylacetoin16; therefore, it should be a good substrate for AcoAB. The feasibility of synthesizing methylacetoin from acetone and acetoin was demonstrated in vitro (Fig. 3). However, the reaction equilibrium strongly favored the reactants. A free energy of 5.37 ± 0.20 kcal mol−1 was determined, which is close to the predicted ΔrG′° of 3.51 kcal mol−1. During the shake-flask experiments, E. coli BL21(DE3) expressing AcoAB produced 0.72 mM methylacetoin from 5 mM acetoin and 200 mM acetone in an M9 medium (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Improving the methylacetoin biosynthesis from acetoin by coupling the conversion to acetaldehyde dehydrogenation.

Acetoin and acetone were incubated with the AcoAB enzyme sample (left) or with the AcoAB and AcoD enzymes with the NAD+ cofactor (right). The reaction mixture was composed of 400 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0), 2 mM MgSO4, 100 mM KCl, 0.2 mM ThDP, 1 mM thioglycol, 2.5 mM NAD+, 50 mM acetone and 1 mM acetoin. The reactions were initiated by adding the enzymes (time = 0) and were conducted at 30°C for 12 h to reach equilibrium. The reaction mixtures were analyzed by GC. I.S., internal standard (1-butanol).

To overcome this thermodynamic limitation and drive the equilibrium to completion, we coupled the reaction to an acetaldehyde dehydrogenation, which has an estimated ΔrG′° of −8.91 kcal mol−1, to obtain a negative overall ΔrG′°. Acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (AcoD) from Alcaligenes eutrophus was chosen because it had the greatest reported preference for NADH over NADPH20. In vitro, the combination of AcoD with AcoAB quantitatively converted acetoin into methylacetoin, with no detectable acetoin remaining (Fig. 3). Similarly, the coexpression of AcoD and AcoAB in E. coli promoted methylacetoin formation from exogenous acetoin. Acetaldehyde dehydrogenase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ALD3) was also tested but did not work as well (Supplementary Fig. S5).

E. coli is not a natural acetoin producer; thus, introducing a biosynthetic pathway to acetoin in E. coli is required to complete the pathway from glucose to methylacetoin. This pathway consists of acetolactate synthase (AlsS) and acetolactate decarboxylase (AlsD), which convert two pyruvate molecules into one acetoin and release two CO2 molecules. Previously, we cloned the alsSD operon from B. subtilis into E. coli and achieved an acetoin titer of over 7.8 g l−1 with greater than 80.2% yield (mole acetoin/mole glucose) in the M9 medium21. By coexpressing alsSD, acoAB and acoD [strain BL21(DE3)/pJXL32,pJXL62B], we produced methylacetoin at a titer of 1.7 g l−1, which is 240-fold that of pathway 1 using the same host and medium [Fig. 2]. In this strain, pyruvate and acetoin can both condense with acetone to produce methylacetoin via AcoAB. However, based on the improved productivity, most of the methylacetoin production can be attributed to acetoin. The new pathway based on the condensation of acetoin and acetone was denoted as pathway 2. Its overall stoichiometry is as follows: 1 Glucose + 1 Acetone → 1 Methylacetoin + 1 Acetate + 2 CO2 + 2 ATP + 3 NADH.

Biosynthesis of 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol

Next, we sought to reduce methylacetoin into another important chemical, 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol. The non-enzymatic hydrogenation of ketones into alcohols involves high H2 pressure and elevated temperatures; therefore, we sought to implement this conversion biologically using a reductase. As such a reductase had not yet been reported, we chose acetoin reductase (also known as 2,3-butanediol dehydrogenase, encoded by bdhA) from B. subtilis as the first candidate based on the similarities between methylacetoin and acetoin22. This selection was also supported by a preliminary experiment indicating that 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol was generated via the addition of methylacetoin to B. subtilis cultures. This preliminary experiment also indicated that E. coli did not reduce methylacetoin into 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol at a detectable rate despite previous studies finding that it possessed a broad-range of alcohol dehydrogenases and could reduce many heterologous substrates, such as 4-hydroxybutyraldehyde23 and isobutyraldehyde24. BdhA enzyme samples were prepared by overexpressing bdhA in an E. coli host BL21(DE3). The in vitro activity was determined from the consumption of NADH, as measured by the change in absorbance at 340 nm. The generation of 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol was confirmed via GC-MS by comparing to the authentic compound (Supplementary Fig. S6). BdhA was found to reduce methylacetoin at a rate of 55% of its natural activity (acetoin reduction) (Supplementary Fig. S7). By introducing BdhA into our methylacetoin producing strains, we produced 8.6 mg l−1 and 1.5 g l−1 of 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol via pathways 1 and 2, respectively [Fig. 2, strains BL21(DE3)/pJXL37 and BL21(DE3)/pJXL37,pJXL62B]. For the pathway 2 strain culture, 9.6 mg l−1 of 2,3-butanediol was also detected as a byproduct, which is likely a reduction product of the intermediate, acetoin, by BdhA (Supplementary Fig. S8).

Metabolic engineering of the host strain

With the functional pathways to methylacetoin and 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol validated, we next aimed to improve their production levels by metabolic engineering of the host strain to channel carbon flux into the end products. First, we investigated whether any native pathways existed in the host background that might compete with these heterogeneous pathways by dissipating a flux of the intermediates. Acetone, acetoin and methylacetoin were added to the E. coli culture at concentrations close to those required by the biosynthesis. No substantial change in their concentrations was observed after 12 h (Supplementary Fig. S9). We then focused on the upstream reactants, increasing the flux toward pyruvate by modifying the native metabolism. Fortunately, because pyruvate is a common precursor for many fermentation products, a series of E. coli strains with enhanced pyruvate biosynthesis have been developed. YYC202ΔldhA is one such strain, with the pathways converting pyruvate into ethanol, acetate, lactate and TCA blocked (resulting in acetate auxotrophy) and with the highest reported pyruvate production (yields of 0.87 g/g of glucose, titer of 110 g l−1)25. Its derivative, YYC202(DE3)ΔldhA, was constructed for harboring T7 expression plasmids and was successfully applied in an acetoin biosynthesis study26. In this study, using YYC202(DE3)ΔldhA as the host to express the biosynthetic pathways improved the production (Fig. 2) in an M9 medium supplemented with 1 g l−1 ammonium acetate, 0.1 g l−1 tryptone, 10 mg l−1 vitamin B1 and 200 mM acetone. Here, the ammonium acetate and tryptone were added to rescue the acetate auxotrophy of the host. Using this metabolic engineered host, pathway 1 produced 9.2 mg l−1 of methylacetoin [Fig. 2, strain YYC202(DE3)ΔldhA/pJXL32] or 8.3 mg l−1 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol when BdhA was included [Fig. 2, strain YYC202(DE3)ΔldhA/pJXL37]. Significantly higher titers were again achieved through pathway 2, which produced 3.4 g l−1 methylacetoin with a yield of 1 g methylacetoin per 2.63 g of glucose and 0.67 g of acetone consumed [Fig. 2, strain YYC202(DE3)ΔldhA/pJXL32,pJXL62B] or 3.2 g l−1 of 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol with a yield of 1 g of 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol per 2.81 g of glucose and 0.75 g of acetone consumed when BdhA was included [Fig. 2, strain YYC202(DE3)ΔldhA/pJXL32,pJXL62B]. The byproduct, 2,3-butanediol, was detected at 21.6 mg l−1 for the YYC202(DE3)ΔldhA/pJXL32,pJXL62B strain (Supplementary Fig. S8).

Discussion

In this study, we report the first microbial routes for the production of methylacetoin and 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol. No natural biosynthetic pathway has been identified for these compounds, which presents a major challenge to this endeavor. However, as with many artificial substances, methylacetoin can be microbiologically degraded, which provides a metabolic relationship between methylacetoin and common cellular metabolites. Based on the functional reversal of methylacetoin biodegradation, we constructed two artificial biosynthetic pathways to methylacetoin formation. The equilibrium, which originally favored degradation, was redirected toward biosynthesis by using alternative substrates with higher free energy, modifying the enzyme complex to block the degradation branch and coupling the synthesis to an exothermic reaction. These pathways were then extended to 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol using a methylacetoin reductase. Notably, similar to the classic ethanol-acetate fermentation, producing 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol via pathway 1 produces one net ATP and is redox balanced, whereas pathway 2 produces two ATP and two NADH (per product). Thus, it is theoretically possible to make these reactions the primary energy-producing pathways and couple them to the growth and maintenance of the host. In that case, a high yield and low process cost can be obtained27. In this study, enzyme screening and metabolic engineering were used to improve the productivity, which resulted in the strains producing methylacetoin at concentrations of 3.4 g l−1 or 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol at 3.2 g l−1. However, the yields were still much lower than the theoretical maxima calculated from the stoichiometry and no contribution of the pathway expression to the cell growth has been observed. Another problem is that pathway 1 has a higher atom efficiency than pathway 2 without the byproducts acetate and 2,3-butanediol but is limited by the low activity of AcoAB toward pyruvate. Future studies require the enzyme engineering of AcoAB to increase its activity and finely tune the enzyme expression levels to reach the potential of these two biosynthetic pathways.

In this study, we used glucose and acetone as the starting feedstocks. Acetone can be produced from acetone-butanol fermentation in large amounts. The expected commercialization of bio-butanol in the near future means that an increased amount of acetone will be available as a renewable byproduct28. Acetone biosynthesis has also been reconstructed using E. coli in high yield from glucose29. Incorporating this acetone pathway into the methylacetoin biosynthesis eliminates the need of exogenous acetone.

To our knowledge, this study presents the first intuitive biosynthetic pathway inspired by the biodegradation of the product compounds; however, some other examples have also demonstrated the reversible nature of biodegradation and thus support the general applicability of our strategy. Recently, a non-natural product, 1,4-butanediol, was biosynthesized via a computationally designed pathway23 that nearly mirrors its biodegradation pathway30. In another study, the engineered reversal of the β-oxidation cycle was used to synthesize fatty acids and derivatives that surpassed natural fatty-acid biosynthesis pathway in product titer and yield31. In addition, many strategies have been proposed to change the direction of reaction equilibria and can be applied to biodegradation reversal, such as switching cofactors [FAD to NAD(P)H or ferredoxin], the physical sequestration of products, enzyme-substrate compartmentalization31,32 and changing the NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ ratio23. The synthetic potential of biological catalysts is masked when the product are not required by living organisms. The biodegradation of artificial substances by natural or laboratory-evolved microbes unmasked this potential in a roundabout manner. As a large number of commodity chemicals can be biodegraded, the exploration of their biodegradation for use in our biodegradation-reversal strategy will help realize the bioproduction of more such useful chemicals.

Methods

Strains and plasmids

E. coli DH5α was used for the plasmid construction. E. coli BL21(DE3) was used for the enzyme sample preparation and product biosynthesis. The E. coli YYC202(DE3)ΔldhA with enhanced pyruvate biosynthesis was generously provided by Prof. Kristala L. J. Prather (Department of Chemical Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology) and used in this study for biosynthesis.

Plasmid isolation, genomic DNA isolation and PCR product purification were conducted using an E.Z.N.A.™ Plasmid Mini Kit, Bacterial DNA Kit and Cycle-Pure kit (OMEGA, Doraville, CA), respectively. The gene chemical syntheses, PCR primer syntheses and DNA sequencing were conducted by the Shanghai Generay Biotech Co. The genes and operons used in this study were chemically synthesized or amplified from the appropriate genomic DNA templates using Pyrobest™ DNA polymerase. Codon optimization was performed using an online tool, OPTIMIZER (http://genomes.urv.es/OPTIMIZER/), based on E. coli codon usage. Expression vectors from pET and pACY systems (Novagen, Madison, WI) were used to harbor the genes or operons in their multicloning sites (Details are provided in Supplementary Methods ). The following antibiotics were used to maintain the plasmids when necessary: kanamycin (Kan, 50 μg ml−1) and chloramphenicol (Cm, 30 μg ml−1).

Preparation of crude enzyme and in vitro enzyme assays

Colonies of strains were picked to LB liquid medium (10 g l−1 Oxoid tryptone, 5 g l−1 Oxoid yeast extract and 10 g l−1 NaCl) containing the appropriate antibiotics and grown overnight at 37°C. The enzymes were expressed by inoculating 0.5 ml of the overnight cultures in 50 ml of fresh LB and incubating at 37°C to an OD600 between 0.6 and 0.9 before inducing with 0.5 mM IPTG for 2 h at 30°C. The cells were collected by centrifuging at 5,000 G and 4°C. The harvested cells were washed twice and resuspended in PBS (containing 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 8.1 mM Na2HPO4 and 1.76 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4). The resuspended cells were then lysed via ultrasonication while cooling in an ice bath. After centrifuging at 20,000 G, the cell-free supernatant was used as the crude enzyme. The total protein concentrations were measured through Bradford assays. Strains containing empty plasmids were used as the control.

Enzyme assays of the methylacetoin synthesis and degradation were performed at 30°C in 50 mM potassium phosphate at a pH of 7.0 with 2 mM MgCl2 and 0.2 mM ThDP. The substrates were added at the indicated concentrations. A reaction mixture composed of 400 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0), 2 mM MgSO4, 100 mM KCl, 0.2 mM ThDP, 1 mM thioglycol, 2.5 mM NAD+, 50 mM acetone and 1 mM acetoin was used to couple methylacetoin synthesis with acetaldehyde dehydrogenation. For methylacetoin (and acetoin) reduction, the reaction mixture was composed of 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0), 0.2 mM NADH and 20 mM methylacetoin or acetoin. The NADH oxidation was monitored at 340 nm and 30°C using a Cary 50 bio UV-visible spectrophotometer.

Analysis of methylacetoin and 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol by gas chromatography and gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy

Pure methylacetoin and 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol were purchased from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA) and Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), respectively. For the methylacetoin analysis, 0.8 ml aqueous samples (culture supernatants or enzyme reactions) were mixed with 50 μl of 100 mM butanol in ethyl acetate (internal standard) and 0.8 ml of ethyl acetate. The mixture was shaken vigorously for 3 min. After centrifuging, the upper organic layer was filtered (0.22 μm) and subjected to GC or GC-MS analysis. For the 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol analysis, 1 ml of the filtered samples were dried in an Eppendorf concentrator for approximately 3 h at 30°C. The residents were resolved in 1 ml of ethyl acetate and centrifuged for 5 min before filtering (0.22 μm) and subjecting to GC or GC-MS analysis.

The GC analyses were performed using an SP-6890 gas chromatography system equipped with a CP-Wax58 column (25 m length, 0.25 mm ID and 0.2 μm film thickness from Varian). The experimental chromatographic conditions were an injector temperature of 200°C, flame ionization detector set to 270°C and N2 carrier gas at 0.05 Mpa and the oven temperature program was as follows: held for 1 min held at 50°C followed by a linear temperature increase of 3°C min−1 to 90°C and then 40°C min−1 to 200°C, which was held for 5 min.

The GC-MS analysis was performed using an Agilent 5975C GC-MS System equipped with a DB-5 ms column (50 m length, 0.25 mm ID and 0.25 μm film thickness from Agilent, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The experimental chromatographic conditions were as follows. The injector was set to 250°C, helium was used as the carrier gas and flowed at 1 ml min−1 and the oven temperature was programmed as follows: held for 1 min at 40°C, followed by a linear temperature increase of 5°C min−1 to 80°C and then 25°C min−1 to 300°C, which was held for 5 min. The MS scan used a source temperature of 230°C, an interface temperature of 300°C, an E energy of 70 eV and a mass scan range from 2 to 150 amu.

Microbial synthesis of methylacetoin and 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol

E. coli BL21(DE3) strain precultures were diluted 100-fold in an M9 minimal salt medium (per liter: 17 g Na2HPO4.12H2O, 3 g KH2PO4, 1 g NH4Cl, 0.5 g NaCl and 0.5 g MgSO4·7H2O) supplemented with 20 g l−1 of D-glucose and the appropriate antibiotics. For the acetate auxotrophic YYC202(DE3)ΔldhA strains, 1 g l−1 of ammonium acetate, 0.1 g l−1 of tryptone and 10 mg l−1 of vitamin B1 were also supplemented. The strains were incubated at 37°C to an OD600 between 0.6 and 0.9. Then, enzyme expression was induced by adding 0.5 mM IPTG and at 30°C. At the time of induction, 200 mM of acetone was added and the flasks were sealed to subject the cultures inside to air-limited conditions. A shaking rate of 180 rpm was maintained throughout. Methylacetoin and 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol production were determined by GC as described above.

Change history

05 December 2013

A correction has been published and is appended to both the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has been fixed in the paper.

References

Lee, J. W. et al. Systems metabolic engineering of microorganisms for natural and non-natural chemicals. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8, 536–546 (2012).

He, M., Leslie, T. M. & Sinicropi, J. A. α-Hydroxy ketone precursors leading to a novel class of electro-optic acceptors. Chem. Mater. 14, 2393–2400 (2002).

Itaya, T., Iida, T., Gomyo, Y., Natsutani, I. & Ohba, M. Efficient synthesis and hydrolysis of cyclic oxalate esters of glycols. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 50, 346–353 (2002).

Villemin, D. & Liao, L. One-pot three steps synthesis of cerpegin. Tetrahedron Lett. 37, 8733–8734 (1996).

Weisang, J. E., Szabo, G. & Maurin, J. Method for the dehydration of diols. United States patent (1976).

Olah, G. A. et al. Acid-catalyzed isomerization of pivalaldehyde to methyl isopropyl ketone via a reactive protosolvated carboxonium ion intermediate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 11556–11561 (2001).

Pugach, J. & Salek, J. S. Preparation of methyl isopropenyl ketone. (1991).

Mironov, G. S. & Farberov, M. I. Commercial methods of synthesis of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes and ketones. Russ Chem Rev 33, 311 (1964).

Davies, N. W. & Madden, J. L. Mandibular gland secretions of two parasitoid wasps (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae). J. Chem. Ecol. 11, 1115–1127 (1985).

Francke, W. & Heemann, V. Lockversuche bei Xyloterus domesticus L. und X. lineatus Oliv. (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) mit 3-Hydroxy-3-methylbutan-2-one. Zeitschrift für Angewandte Entomologie 75, 67–72 (1974).

Dekant, W., Bernauer, U., Rosner, E. & Amberg, A. Biotransformation of MTBE, ETBE and TAME after inhalation or ingestion in rats and humans. Research report (Health Effects Institute), 29 (2001).

Oppermann, B. Utilization of methylacetoin by the strict anaerobe Pelobacter carbinolicus and consequences for the catabolism of acetoin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 55, 47–52 (1988).

Jankowski, M. D., Henry, C. S., Broadbelt, L. J. & Hatzimanikatis, V. Group contribution method for thermodynamic analysis of complex metabolic networks. Biophys. J. 95, 1487–1499 (2008).

Weber, A. L. Chemical constraints governing the origin of metabolism: the thermodynamic landscape of carbon group transformations under mild aqueous conditions. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 32, 333–357 (2002).

Lin, H., Vadali, R. V., Bennett, G. N. & San, K.-Y. Increasing the acetyl-CoA pool in the presence of overexpressed phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase or pyruvate carboxylase enhances succinate production in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Prog. 20, 1599–1604 (2004).

Oppermann, F. B., Schmidt, B. & Steinbuchel, A. Purification and characterization of acetoin:2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol oxidoreductase, dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase and dihydrolipoamide acetyltransferase of the Pelobacter carbinolicus acetoin dehydrogenase enzyme system. J. Bacteriol. 173, 757–767 (1991).

Meyer, D. et al. Conversion of pyruvate decarboxylase into an enantioselective carboligase with biosynthetic potential. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 3609–3616 (2011).

Xiao, Z. & Xu, P. Acetoin Metabolism in Bacteria. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 33, 127–140 (2007).

Lehwald, P., Richter, M., Röhr, C., Liu, H. & Müller, M. Enantioselective intermolecular aldehyde–ketone cross-coupling through an enzymatic carboligation reaction. Angew. Chem. 122, 2439–2442 (2010).

Bennett, B. D. et al. Absolute metabolite concentrations and implied enzyme active site occupancy in Escherichia coli. Nat Chem Biol 5, 593–599 (2009).

Jiang, X. et al. Induction of gene expression in bacteria at optimal growth temperatures. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1–9, dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00253-012-4633-8 (2012).

Nicholson, W. L. The Bacillus subtilis ydjL (bdhA) gene encodes acetoin reductase/2,3-butanediol dehydrogenase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 6832–6838 (2008).

Yim, H. et al. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for direct production of 1,4-butanediol. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 445–452 (2011).

Atsumi, S. et al. Engineering the isobutanol biosynthetic pathway in Escherichia coli by comparison of three aldehyde reductase/alcohol dehydrogenase genes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 85, 651–657 (2010).

Xu, P., Qiu, J., Gao, C. & Ma, C. Biotechnological routes to pyruvate production. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 105, 169–175 (2008).

Nielsen, D. R., Yoon, S.-H., Yuan, C. J. & Prather, K. L. J. Metabolic engineering of acetoin and meso-2, 3-butanediol biosynthesis in E. coli. Biotechnology Journal 5, 274–284 (2010).

Weusthuis, R. A., Lamot, I., van der Oost, J. & Sanders, J. P. M. Microbial production of bulk chemicals: development of anaerobic processes. Trends Biotechnol. 29, 153–158 (2011).

Haveren, J. v., Scott, E. L. & Sanders, J. Bulk chemicals from biomass. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining 2, 41–57 (2008).

Hanai, T., Atsumi, S. & Liao, J. C. Engineered synthetic pathway for isopropanol production in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 7814–7818 (2007).

Struys, E. A. et al. Metabolism of γ-hydroxybutyrate to d-2-hydroxyglutarate in mammals: further evidence for d-2-hydroxyglutarate transhydrogenase. Metabolism 55, 353–358 (2006).

Dellomonaco, C., Clomburg, J. M., Miller, E. N. & Gonzalez, R. Engineered reversal of the β-oxidation cycle for the synthesis of fuels and chemicals. Nature 476, 355–359.

Bond-Watts, B. B., Bellerose, R. J. & Chang, M. C. Y. Enzyme mechanism as a kinetic control element for designing synthetic biofuel pathways. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 222–227 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Qingdao Applied Basic Research Program [12-1-4-9-(5)-jch], the Qingdao Science Technology Research Program (12-4-1-45-nsh), the National 863 Project of China (SS2013AA050703-2) and the Twelfth Five-year Science and Technology Project (2012BAD32B06).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.J., Haibo Zhang., J.Y., Y.Z. and M.X. designed the experiments. X.J., Haibo Zhang., M.X., Y.Z., J.Y., R.Z., T.C. and D.F. performed the experiments. X.J., Haibo Zhang., M.X., W.L., X.X., Y.C., F.J. and Huibin Zou wrote the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

supplementary info

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, X., Zhang, H., Yang, J. et al. Biodegradation-inspired bioproduction of methylacetoin and 2-methyl-2,3-butanediol. Sci Rep 3, 2445 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02445

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02445

This article is cited by

-

Biosynthesis of acetylacetone inspired by its biodegradation

Biotechnology for Biofuels (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.