Key Points

-

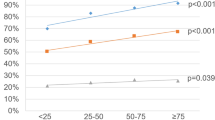

The incidence of prostate cancer in young men (aged ≤55 years) has increased sharply over the past two decades, making early-onset prostate cancer an important emerging issue for public health

-

Increased screening in young men could account for some, but not all, of the increase in incidence of early-onset prostate cancer

-

Advanced-stage and high-grade early-onset prostate cancer might be a distinct clinicopathological subtype with more rapid progression to disease-specific death than late-onset prostate cancer of similar stage and grade

-

Men with early-onset prostate cancer tend to have a greater genetic risk than their older peers, making this group an ideal resource for investigating genetic susceptibility to prostate cancer

Abstract

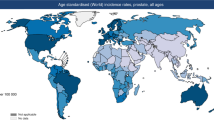

Prostate cancer is considered a disease of older men (aged >65 years), but today over 10% of new diagnoses in the USA occur in young men aged ≤55 years. Early-onset prostate cancer, that is prostate cancer diagnosed at age ≤55 years, differs from prostate cancer diagnosed at an older age in several ways. Firstly, among men with high-grade and advanced-stage prostate cancer, those diagnosed at a young age have a higher cause-specific mortality than men diagnosed at an older age, except those over age 80 years. This finding suggests that important biological differences exist between early-onset prostate cancer and late-onset disease. Secondly, early-onset prostate cancer has a strong genetic component, which indicates that young men with prostate cancer could benefit from evaluation of genetic risk. Furthermore, although the majority of men with early-onset prostate cancer are diagnosed with low-risk disease, the extended life expectancy of these patients exposes them to long-term effects of treatment-related morbidities and to long-term risk of disease progression leading to death from prostate cancer. For these reasons, patients with early-onset prostate cancer pose unique challenges, as well as opportunities, for both research and clinical communities. Current data suggest that early-onset prostate cancer is a distinct phenotype—from both an aetiological and clinical perspective—that deserves further attention.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Howlader, N. et al. (eds) SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2009 (Vintage 2009 Populations), National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD [online], (2012).

Siegel, R., Naishadham, D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J. Clin. 62, 10–29 (2012).

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat Database: Incidence–SEER 17 Regs Research Data + Hurricane Impacted Louisiana Cases 2010.

Droz, J. P. et al. Management of prostate cancer in older men: recommendations of a working group of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology. BJU Int. 106, 462–469 (2010).

Alibhai, S. M. et al. Is there age bias in the treatment of localized prostate carcinoma? Cancer 100, 72–81 (2004).

Potosky, A. L. et al. Five-year outcomes after prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer: the prostate cancer outcomes study. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 96, 1358–1367 (2004).

Gronberg, H., Damber, J. E., Jonsson, H. & Lenner, P. Patient age as a prognostic factor in prostate cancer. J. Urol. 152, 892–895 (1994).

Harrison, G. S. The prognosis of prostatic cancer in the younger man. Br. J. Urol. 55, 315–320 (1983).

Benson, M. C., Kaplan, S. A. & Olsson, C. A. Prostate cancer in men less than 45 years old: influence of stage, grade and therapy. J. Urol. 137, 888–890 (1987).

Byar, D. P. & Mostofi, F. K. Cancer of the prostate in men less than 50 years old: an analysis of 51 cases. J. Urol. 102, 726–733 (1969).

Huben, R. et al. Carcinoma of prostate in men less than fifty years old. Data from American College of Surgeons' National Survey. Urology 20, 585–588 (1982).

Silber, I. & McGavran, M. H. Adenocarcinoma of the prostate in men less than 56 years old: a study of 65 cases. J. Urol. 105, 283–285 (1971).

Smedley, H. M. et al. Age and survival in prostatic carcinoma. Br. J. Urol. 55, 529–533 (1983).

Riopel, M. A. et al. Radical prostatectomy in men less than 50 years old. Urol. Oncol. 1, 80–83 (1995).

Carter, H. B., Epstein, J. I. & Partin, A. W. Influence of age and prostate-specific antigen on the chance of curable prostate cancer among men with nonpalpable disease. Urology 53, 126–130 (1999).

Ruska, K. M., Partin, A. W., Epstein, J. I. & Kahane, H. Adenocarcinoma of the prostate in men younger than 40 years of age: diagnosis and treatment with emphasis on radical prostatectomy findings. Urology 53, 1179–1183 (1999).

Smith, C. V. et al. Prostate cancer in men age 50 years or younger: a review of the Department of Defense Center for Prostate Disease Research multicenter prostate cancer database. J. Urol. 164, 1964–1967 (2000).

Khan, M. A., Han, M., Partin, A. W., Epstein, J. I. & Walsh, P. C. Long-term cancer control of radical prostatectomy in men younger than 50 years of age: update 2003. Urology 62, 86–91 (2003).

Magheli, A. et al. Impact of patient age on biochemical recurrence rates following radical prostatectomy. J. Urol. 178, 1933–1937 (2007).

Twiss, C., Slova, D. & Lepor, H. Outcomes for men younger than 50 years undergoing radical prostatectomy. Urology 66, 141–146 (2005).

Burri, R. J. et al. Young men have equivalent biochemical outcomes compared with older men after treatment with brachytherapy for prostate cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 77, 1315–1321 (2010).

Merrick, G. S. et al. Brachytherapy in men aged < or = 54 years with clinically localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 98, 324–328 (2006).

Shapiro, E. Y. et al. Long-term outcomes in younger men following permanent prostate brachytherapy. J. Urol. 181, 1665–1671 (2009).

Nguyen, T. D. et al. The curative role of radiotherapy in adenocarcinoma of the prostate in patients under 55 years of age: a rare cancer network retrospective study. Radiother. Oncol. 77, 286–289 (2005).

Rossi, C. J. Jr et al. Influence of patient age on biochemical freedom from disease in patients undergoing conformal proton radiotherapy of organ-confined prostate cancer. Urology 64, 729–732 (2004).

Johnstone, P. A. et al. Effect of age on biochemical disease-free outcome in patients with T1-T3 prostate cancer treated with definitive radiotherapy in an equal-access health care system: a radiation oncology report of the Department of Defense Center for Prostate Disease Research. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 55, 964–969 (2003).

Wilson, J. M., Kemp, I. W. & Stein, G. J. Cancer of the prostate. Do younger men have a poorer survival rate? Br. J. Urol. 56, 391–396 (1984).

Tjaden, H. B., Culp, D. A. & Flocks, R. H. Clinical adenocarcinoma of the prostate in patients under 50 years of age. J. Urol. 93, 618–621 (1965).

Bratt, O., Kristoffersson, U., Olsson, H. & Lundgren, R. Clinical course of early onset prostate cancer with special reference to family history as a prognostic factor. Eur. Urol. 34, 19–24 (1998).

Johnson, D. E., Lanieri, J. P. & Ayala, A. G. Prostatic adenocarcinoma occurring in men under 50 years of age. J. Surg. Oncol. 4, 207–216 (1972).

Merrill, R. M. & Bird, J. S. Effect of young age on prostate cancer survival: a population-based assessment (United States). Cancer Causes Control 13, 435–443 (2002).

Lin, D. W., Porter, M. & Montgomery, B. Treatment and survival outcomes in young men diagnosed with prostate cancer: a Population-based Cohort Study. Cancer 115, 2863–2871 (2009).

CISNET. Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network [online].

Tsodikov, A., Szabo, A. & Wegelin, J. A population model of prostate cancer incidence. Stat. Med. 25, 2846–2866 (2006).

Chefo, S. & Tsodikov, A. Stage-specific cancer incidence: an artificially mixed multinomial logit model. Stat. Med. 28, 2054–2076 (2009).

Zelen, M. & Feinleib, M. On the theory of screening for chronic diseases. Biometrika 56, 601–614 (1969).

Brawley, O. W. Prostate cancer epidemiology in the United States. World J. Urol. 30, 195–200 (2012).

Zeegers, M. P., Jellema, A. & Ostrer, H. Empiric risk of prostate carcinoma for relatives of patients with prostate carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Cancer 97, 1894–1903 (2003).

Brandt, A., Bermejo, J. L., Sundquist, J. & Hemminki, K. Age-specific risk of incident prostate cancer and risk of death from prostate cancer defined by the number of affected family members. Eur. Urol. 58, 275–280 (2010).

Chen, Y. C., Page, J. H., Chen, R. & Giovannucci, E. Family history of prostate and breast cancer and the risk of prostate cancer in the PSA era. Prostate 68, 1582–1591 (2008).

Kicinski, M., Vangronsveld, J. & Nawrot, T. S. An epidemiological reappraisal of the familial aggregation of prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 6, e27130 (2011).

Carter, B. S., Beaty, T. H., Steinberg, G. D., Childs, B. & Walsh, P. C. Mendelian inheritance of familial prostate cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 89, 3367–3371 (1992).

Lynch, H. T. et al. Early age of onset in familial breast cancer. Genetic and cancer control implications. Arch. Surg. 111, 126–131 (1976).

Lynch, H. T. & de la Chapelle, A. Genetic susceptibility to non-polyposis colorectal cancer. J. Med. Genet. 36, 801–818 (1999).

Vasen, H. F. et al. The epidemiology of endometrial cancer in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 14, 1675–1678 (1994).

Lange, E. M. et al. Early onset prostate cancer has a significant genetic component. Prostate 72, 147–156 (2012).

Lindstrom, S. et al. Common genetic variants in prostate cancer risk prediction—results from the NCI Breast and Prostate Cancer Cohort Consortium (BPC3). Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 21, 437–444 (2012).

Dennis, L. K. & Dawson, D. V. Meta-analysis of measures of sexual activity and prostate cancer. Epidemiology 13, 72–79 (2002).

Rohrmann, S. et al. Meat and dairy consumption and subsequent risk of prostate cancer in a US cohort study. Cancer Causes Control 18, 41–50 (2007).

Lynch, B. M. Sedentary behavior and cancer: a systematic review of the literature and proposed biological mechanisms. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 19, 2691–2709 (2010).

Ostrander, E. A. & Johannesson, B. Prostate cancer susceptibility loci: finding the genes. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 617, 179–190 (2008).

Manolio, T. A. et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature 461, 747–753 (2009).

Zeggini, E. et al. An evaluation of HapMap sample size and tagging SNP performance in large-scale empirical and simulated data sets. Nat. Genet. 37, 1320–1322 (2005).

Cirulli, E. T. & Goldstein, D. B. Uncovering the roles of rare variants in common disease through whole-genome sequencing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 415–425 (2010).

Nelson, M. R. et al. An abundance of rare functional variants in 202 drug target genes sequenced in 14,002 people. Science 337, 100–104 (2012).

Tennessen, J. A. et al. Evolution and functional impact of rare coding variation from deep sequencing of human exomes. Science 337, 64–69 (2012).

Keinan, A. & Clark, A. G. Recent explosive human population growth has resulted in an excess of rare genetic variants. Science 336, 740–743 (2012).

Ewing, C. M. et al. Germline mutations in HOXB13 and prostate-cancer risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 141–149 (2012).

Sreenath, T., Orosz, A., Fujita, K. & Bieberich, C. J. Androgen-independent expression of hoxb-13 in the mouse prostate. Prostate 41, 203–207 (1999).

Kim, Y. R. et al. HOXB13 promotes androgen independent growth of LNCaP prostate cancer cells by the activation of E2F signaling. Mol. Cancer 9, 124 (2010).

Laitinen, V. H. et al. HOXB13 G84E mutation in Finland: population-based analysis of prostate, breast, and colorectal cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 22, 452–460 (2013).

Chen, Z. et al. The G84E mutation of HOXB13 is associated with increased risk for prostate cancer: results from the REDUCE trial. Carcinogenesis 34, 1260–1264 (2013).

Kluzniak, W. et al. The G84E mutation in the HOXB13 gene is associated with an increased risk of prostate cancer in Poland. Prostate 73, 542–548 (2013).

Stott-Miller, M. et al. HOXB13 mutations in a population-based, case-control study of prostate cancer. Prostate 73, 634–641 (2013).

Witte, J. S. et al. HOXB13 mutation and prostate cancer: studies of siblings and aggressive disease. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 22, 675–680 (2013).

Xu, J. et al. HOXB13 is a susceptibility gene for prostate cancer: results from the International Consortium for Prostate Cancer Genetics (ICPCG). Hum. Genet. 132, 5–14 (2013).

Gudmundsson, J. et al. A study based on whole-genome sequencing yields a rare variant at 8q24 associated with prostate cancer. Nat. Genet. 44, 1326–1329 (2012).

Breyer, J. P., Avritt, T. G., McReynolds, K. M., Dupont, W. D. & Smith, J. R. Confirmation of the HOXB13 G84E germline mutation in familial prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 21, 1348–1353 (2012).

Zheng, S. L. et al. Cumulative association of five genetic variants with prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 910–919 (2008).

Salinas, C. A. et al. Clinical utility of five genetic variants for predicting prostate cancer risk and mortality. Prostate 69, 363–372 (2009).

Helfand, B. T. et al. Genetic prostate cancer risk assessment: common variants in 9 genomic regions are associated with cumulative risk. J. Urol. 184, 501–505 (2010).

Zheng, S. L. et al. Genetic variants and family history predict prostate cancer similar to prostate-specific antigen. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 1105–1111 (2009).

Xu, J. et al. Estimation of absolute risk for prostate cancer using genetic markers and family history. Prostate 69, 1565–1572 (2009).

Sun, J. et al. Chromosome 8q24 risk variants in hereditary and non-hereditary prostate cancer patients. Prostate 68, 489–497 (2008).

Nam, R. K. et al. Utility of incorporating genetic variants for the early detection of prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 1787–1793 (2009).

Beuten, J. et al. Single and multigenic analysis of the association between variants in 12 steroid hormone metabolism genes and risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 18, 1869–1880 (2009).

Sun, J. et al. Cumulative effect of five genetic variants on prostate cancer risk in multiple study populations. Prostate 68, 1257–1262 (2008).

Penney, K. L. et al. Evaluation of 8q24 and 17q Risk Loci and Prostate Cancer Mortality. Clin. Cancer Res. 15, 3223–3230 (2009).

Sun, J. et al. Inherited genetic markers discovered to date are able to identify a significant number of men at considerably elevated risk for prostate cancer. Prostate 71, 421–430 (2011).

Helfand, B. T., Kan, D., Modi, P. & Catalona, W. J. Prostate cancer risk alleles significantly improve disease detection and are associated with aggressive features in patients with a “normal” prostate specific antigen and digital rectal examination. Prostate 71, 394–402 (2011).

Aly, M. et al. Polygenic risk score improves prostate cancer risk prediction: results from the Stockholm-1 cohort study. Eur. Urol. 60, 21–28 (2011).

Wiklund, F. E. et al. Established prostate cancer susceptibility variants are not associated with disease outcome. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 18, 1659–1662 (2009).

Klein, R. J. et al. Evaluation of multiple risk-associated single nucleotide polymorphisms versus prostate-specific antigen at baseline to predict prostate cancer in unscreened men. Eur. Urol. 61, 471–477 (2012).

Schroder, F. & Kattan, M. W. The comparability of models for predicting the risk of a positive prostate biopsy with prostate-specific antigen alone: a systematic review. Eur. Urol. 54, 274–290 (2008).

Montie, J. E. & Smith, J. A. Whitmoreisms: memorable quotes from Willet F. Whitmore Jr, M.D. Urology 63, 207–209 (2004).

Wilt, T. J. et al. Radical prostatectomy versus observation for localized prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 203–213 (2012).

Draisma, G. et al. Lead time and overdiagnosis in prostate-specific antigen screening: importance of methods and context. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 101, 374–383 (2009).

Barry, M. J. & Mulley, A. J. Jr. Why are a high overdiagnosis probability and a long lead time for prostate cancer screening so important? J. Natl Cancer Inst. 101, 362–363 (2009).

Lin, D. W. et al. Genetic variants in the LEPR, CRY1, RNASEL, IL4, and ARVCF genes are prognostic markers of prostate cancer-specific mortality. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 20, 1928–1936 (2011).

Cooperberg, M. R., Broering, J. M. & Carroll, P. R. Time trends and local variation in primary treatment of localized prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 1117–1123 (2010).

Sidana, A. et al. Treatment decision-making for localized prostate cancer: what younger men choose and why. Prostate 72, 58–64 (2012).

Zeliadt, S. B. et al. Why men choose one treatment over another: a review of patient decision making for localized prostate cancer. Cancer 106, 1865–1874 (2006).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics [online], (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors' research work was supported by NIH research grants no R01 CA79596 (K.A.C.), R01 CA136621 to (K.A.C.), SPORE P50 CA69568 (A.T., K.A.C.) and CISNET U01 CA157224 (A.T.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.A.S., A.T. and K.A.C. researched data for the manuscript. C.A.S., M.I.-H. and K.A.C. made substantial contributions to discussion of content and wrote the article. A.T., M.I.-H. and K.A.C. reviewed the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

K.A.C. has received grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA79596, R01 CA136621, SPORE P50 CA69568). A.T. has received a grant from the National Institutes of Health (CISNET U01 CA157224, SPORE P50 CA69568). The other authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Salinas, C., Tsodikov, A., Ishak-Howard, M. et al. Prostate cancer in young men: an important clinical entity. Nat Rev Urol 11, 317–323 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2014.91

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2014.91

This article is cited by

-

Global and regional quality of care index for prostate cancer: an analysis from the Global Burden of Disease study 1990–2019

Archives of Public Health (2023)

-

Global burden of prostate cancer attributable to smoking among males in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019

BMC Cancer (2023)

-

Neighbourhood social deprivation and risk of prostate cancer

British Journal of Cancer (2023)

-

Molecular characteristics of Asian male BRCA-related cancers

Breast Cancer Research and Treatment (2023)

-

Development of a redox-related prognostic signature for predicting biochemical-recurrence-free survival of prostate cancer*

Oncology and Translational Medicine (2023)