2011 the science year in brief

-

January

-

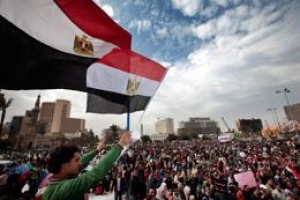

Arab Spring

Arab Spring offers hope for research freedom

Elated scientists joined jubilant revellers throughout Egypt on 11 February, when Hosni Mubarak resigned after 30 years as the nation’s president. He stepped down a few weeks after popular uprisings forced out Tunisian President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali. With dictators ousted, many researchers remain optimistic that the Arab Spring’s new freedoms will lead to progress in science, education and democracy. But by the time Libya’s ruler, Muammar Gaddafi, was killed in October, it was increasingly clear that change would be slow in coming — and would depend heavily on those who take power. One immediate effect of the revolutions was to throw archaeology into turmoil: foreign archaeologists had to leave both Libya and Egypt, and Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities was left paralysed after its controversial but charismatic leader, Zahi Hawass, was forced to leave office in July.

• The Arab Spring offers hope but no quick fix

• Revolution offers chance for Libyan archaeology

• Archaeology meets politics: Spring comes to ancient Egypt

Image: L. Pitarakis/AP

-

Food Prices

World food prices reach record high

"2011's biggest problem will be food," John Beddington, the UK government's chief scientific adviser, told a meeting in London on 28 February. Indeed, world food prices reached a record high at the start of the year, as indexed by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, in Rome. In June, the organization warned that prices were likely to stay “high and volatile”. Unfavourable weather, rising oil prices, political unrest and the nuclear disaster in Japan all helped to unsettle the food market.

• Food prices reach record high

• Climate-smart agriculture is needed

Image source: FAO

-

-

February

-

Genzyme bought

Sanofi pays $20 billion for Genzyme

The pattern has become a familiar one in recent years: a pharmaceutical giant acquires a smaller biotech company as a way of stocking up on new drug candidates. Sanofi’s $20-billion deal for Genzyme, announced on 16 February, was the industry’s biggest acquisition in two years. But some observers fear that Genzyme’s shift to the status of a branch plant will dilute the home-grown innovative culture for which the pioneering biotech company is known, and drain some of the dynamism from the biotech hub it has helped to create in the area around Boston.

• Genzyme deal set to alter biotech landscape

Image: K. Ma/Bloomberg/Getty

-

-

March

-

Mourning Glory

NASA’s Earth-observation Glory mission crashes

In a serious blow to Earth observation and solar science, NASA's Glory mission crashed on 4 March, shortly after lift-off. The protective fairing surrounding the satellite failed to separate from the Taurus XL rocket that carried it, dragging the craft into icy waters near Antarctica. The failure was the second major loss for NASA's Earth-observation programme in as many years. In February 2009, NASA lost its Orbiting Carbon Observatory — intended to track atmospheric carbon dioxide levels — in a strikingly similar incident.

• NASA satellite crashes to Earth

Image: A. Galvan III/AP

-

Japan’s earthquake

Japan’s deadly tsunami

Even Japan, the nation best prepared for a tsunami, was overwhelmed by the monster waves that struck the coast of Sendai on 11 March, following a magnitude-9.0 earthquake. Tens of thousands of people died, and hundreds of thousands were displaced. But it was the meltdown of three tsunami-damaged reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant — the worst nuclear disaster since Chernobyl — that soon gripped the world’s attention. Fortunately, wind carried much of the radioactivity out to sea. It took nine months before the reactors could be declared safely in cold shutdown; and it will take decades and hundreds of billions of dollars to clean up the plant.

-

Stem cells bad

Studies question value of reprogrammed

stem cellsPodcast interview: Stem cells

Nature Podcast: Erika Check Hayden discusses the problems with creating induced pluripotent stem cells

You may need a more recent browser or to install the latest version of the Adobe Flash Plugin.Scientists’ early love affair with induced pluripotent stem cells gave way this year to a more mature assessment of their abilities. In the spring, it seemed that only the cells’ bad points were gaining attention. The reprogrammed cells can trigger immune reactions in mice, and may contain genetic abnormalities, for instance.

-

Mercury orbited

MESSENGER probe becomes first craft to orbit Mercury

It's a long road to the Solar System's innermost planet. Because of Mercury's position deep in the Sun's gravity well, NASA's MESSENGER spacecraft needed a six-year flight, passing Earth once, Venus twice and Mercury itself three times, to shed enough energy to orbit the planet. But on 18 March, the craft reached its goal, beginning a long-awaited survey of the Sun-scorched world. It will search for hints of ice within permanently shadowed craters near the planet's poles, and make magnetic-field measurements that could reveal structural details about Mercury's iron core.

• NASA mission set to orbit Mercury

Image: Science/Carnegie Inst./ASU/Johns Hopkins Univ./NASA

-

-

April

-

Stem cells good

Mouse stem cells form retina-in-a-dish

Podcast interview: Retina in a dish

Nature Podcast: Robin Ali discusses how to grow a ‘retina in a dish’ from mouse embryonic stem cell

You may need a more recent browser or to install the latest version of the Adobe Flash Plugin.Yoshiki Sasai’s team at the RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology in Kobe, Japan, led research this year showing that mouse embryonic stem cells could be coaxed into precise three-dimensional assemblies of complex biological tissue. In April, they published work on retinal tissue, and followed that up in November with a working anterior pituitary gland. Such studies could pave the way for treatments when these organs malfunction — such as in eye disease or in hypopituitarism.

-

Funding cuts

Cuts to US science funding presage

budget battles

In April, scientists at US federal agencies avoided the prospect of a government shutdown when congressional leaders agreed an outline budget that only took around 1% from most science agencies. But that fractious debate foreshadowed a much tougher battle over the 2012 budget. In the end, most agencies saw modest increases for 2012, but the prospect looms of across-the-board cuts for science agencies in 2013.

• US budget a taste of battles to come

• US science agencies dodge deep cuts

• Nature Special: US budget crisis

Image: R. T. Nowitz/Corbis

-

-

May

-

Human epoch

Researchers meet to discuss the ‘Anthropocene’

Geologists gathered in May to discuss whether human impact on the planet deserved recognition by declaring a new geological epoch, the Anthropocene. "We are in the process of formalizing it," says Michael Ellis, head of the climate-change programme of the British Geological Survey in Nottingham, UK. He and others hope that adopting the term will shift the thinking of policy-makers. "It should remind them of the global and significant impact that humans have," says Ellis. But not everyone is behind the idea. "Some think it premature, perhaps hubristic, perhaps nonsensical," says Jan Zalasiewicz, a stratigrapher at the University of Leicester, UK.

• Human influence comes of age

Image: S. Cantrell/NAS

-

Hepatitis C cure

FDA approves first of wave of hepatitis C drugs

In May, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first therapies tailored to target the hepatitis C virus (HCV). Victrelis (boceprevir), made by Merck of New Jersey, targets an HCV protein called the NS3 protease, which is crucial for proper processing of the virus’s proteins. Another drug that targets NS3 — Incivek (telaprevir), which is made by Vertex Pharmaceuticals in Cambridge, Massachusetts — was also approved. But these drugs are only the beginning of a revolution in HCV treatment. Researchers are working on drugs that target many aspects of the virus's biology. Used in combination, these might thwart HCV's ability to evolve resistance.

• New drug targets raise hopes for hepatitis C cure

• US regulators approve first targeted hepatitis C drug

Image: Ramon Andrade 3Dciencia/SPL

-

IPCC reform

IPCC announces major reforms

After months of soul-searching, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) agreed on reforms intended to restore confidence in its integrity and its assessments of climate science. Created as a United Nations body in 1988 to analyse the latest knowledge about Earth's changing climate, the IPCC has worked with thousands of scientists, and shared the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007. But its reputation crumbled when its leadership failed to respond effectively to mistakes that had slipped into its most recent assessment report. The InterAcademy Council, a consortium of national science academies, recommended better governance and transparency in the face of more public scrutiny.

• Major reform for climate body

• Climate panel says prepare for weird weather

Image: S. Das/Panos

-

Nuclear phase-out

Germany announces plans to phase out nuclear power

In the wake of the disaster at Fukushima, Germany's government said on 30 May that it plans to shut down all 17 of its nuclear power stations by 2022. The government wants to double the country's use of renewable resources to generate electricity by 2020 — but even that would not fill the energy gap left by the nuclear shutdown. Switzerland, Italy and Japan also vowed to leave nuclear energy behind, and Europe and the United States imposed ‘stress tests’ on their nuclear plants. But not all countries altered their nuclear plans: France and China notably announced no intention to slow down the construction of new reactors.

• China forges ahead with nuclear energy

-

-

June

-

E. coli panic

E. coli outbreak in northern Europe

Through May and June, a severe strain of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli infected more than 4,300 people across northern Europe — mostly in Germany — and killed more than 50 people. It was not until 26 July that the Robert Koch Institute in Berlin declared the outbreak officially over. In the end, the duration of the outbreak and the time taken to identify its source compared favourably with previous E. coli outbreaks, but it exposed deficiencies in Germany’s disease-reporting system, which the country has vowed to correct.

• Microbe outbreak panics Europe

• Germany learns from E. coli outbreak

Image: Martin Oeggerli/SPL

-

Age of Aquarius

NASA’s Aquarius probe launches to measure ocean salinity

After two failed launches for NASA's Earth observation projects, the space agency scored a success: Aquarius, its satellite to measure the saltiness of the oceans, reached orbit on 10 June and produced its first map in September. The probe picks up weak microwave radiation emitted naturally by the ocean. This radiation varies according to the electrical conductivity of the water, which in turn is tied to its salinity. Because salinity is linked to evaporation and water density, the data could help scientists to confirm theories about the global water cycle and its response to climate change.

• NASA ready to test the waters

Image: NASA/GSFC/JPL-Caltech

-

-

July

-

Harvard scandal

Disgraced psychologist Marc Hauser resigns

Marc Hauser, the prominent evolutionary psychologist whose career has been blotted by misconduct findings, resigned from Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in July. He had been due to return from a year-long leave of absence taken after Harvard revealed in August 2010 that an internal investigation had found him responsible for eight counts of scientific misconduct. Details about exactly what happened remain murky, and the US Office of Research Integrity is still investigating.

• Marc Hauser resigns from Harvard University

Image: R. Friedman/Corbis

-

Receptor revealed

Crystal structure of G-protein-coupled receptor

Nearly every function of the human body, from sight and smell to heart rate and neuronal communication, depends on G-protein-coupled receptors. Lodged in the fatty membranes that surround cells, they detect hormones, odours, chemical neurotransmitters and other signals outside the cell, and then convey their messages to the interior by activating one of several types of G protein. The G protein, in turn, triggers a plethora of other events. The receptors make up one of the largest families of human proteins and are the targets of one-third to one-half of drugs. So it was a fundamental breakthrough when researchers led by Brian Kobilka at Stanford University in Chicago, Illinois, published the crystal structure of the G-protein-coupled receptor locked with its protein partner.

• Cell signalling caught in the act

• Cell signalling: it’s all about the structure

Image: S. G. F. Rasmussen et al. Nature 477, 549–555 (2011)

-

Shuttle's end

The US retires its space-shuttle fleet

After 30 years and 135 missions, from the launch of Columbia in 1981, through the loss of Challenger in 1986 and Columbia in 2003, NASA's Space Transportation System is at an end. The shuttle programme, which delivered the Hubble Space Telescope and serviced the International Space Station, officially concluded on 21 July with the touchdown of Atlantis at Kennedy Space Center, Florida. Eventually, private companies will offer new commercial space-flight options, but without its shuttle programme, NASA may struggle to find a clear sense of mission. Even its flagship space project, the James Webb Space Telescope, is desperately over budget and likely to be delayed for years.

• Nature news special: 30 years of the space shuttle

Podcast: The end of the space shuttle

Nature Podcast: After the end of the space shuttle programme, what’s next for NASA?

You may need a more recent browser or to install the latest version of the Adobe Flash Plugin. -

Stem-cell lawsuit

US judge throws out lawsuit on human embryonic stem cells

Podcast interview: Deisher

Nature Podcast: Meredith Wadman discusses stem-cell crusader Theresa Deisher

You may need a more recent browser or to install the latest version of the Adobe Flash Plugin.Was the case a fluke or a forewarning? After a federal judge threw out a lawsuit that sought to halt US government funding of research using human embryonic stem cells, scientists who depend on that support were left wondering whether the battle is truly over, or is merely moving on to a different arena. Scientists laboured under the threat of a funding shutdown for 11 months as the case unfolded, even experiencing an actual research shutdown for 17 days during a temporary injunction in 2010. Some observers say it will take years to recover from the impact of the lawsuit. "Things have changed permanently. It's not just going to go back to the way it was — not immediately," says Meri Firpo, who researches stem-cell therapies at the University of Minnesota Stem Cell Institute in Minneapolis.

-

-

August

-

To

Jupiter!Juno spacecraft launches for Jupiter

NASA's Juno spacecraft launched on 5 August, bound for Jupiter. The US$1.1-billion mission will take five years to reach the Solar System's largest planet, which it will swing round 33 times in a highly elliptical orbit. Juno will probe the Jovian atmosphere for water vapour, and look for signs of a solid core.

• Closing in on Jupiter's past

Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech

-

Solar

woesSolar firm Solyndra goes bankrupt

When high-profile US start-up firm Solyndra said that it would file for bankruptcy and lay off some 1,100 employees, a political firestorm was kicked up around the Department of Energy, which had given the company, based in Fremont, California, a $535-million loan guarantee. But besides the politicking, the bankruptcy underlined the struggles of US solar-energy companies to compete in the face of cheaper products from China. And it wasn’t just US companies: throughout the year, slow demand for solar panels, oversupply of products and materials, and subsidy cuts bit heavily into the industry's profits, so that firms in Germany and China also missed sales targets. For consumers benefiting from cheaper solar power, this was all good news of course, a welcome streamlining and maturing of a young industry weaning itself off subsidies.

• Amid political storm, Chu defends Solyndra decision

Image: R. Nickelsberg/Getty

-

-

September

-

Fountain of youth?

Study queries sirtuins’ link with longevity

Podcast interview: Sirtuins

Nature Podcast: Has research into life extension reached its sell-by date?

You may need a more recent browser or to install the latest version of the Adobe Flash Plugin.A widely touted — but controversial — molecular fountain of youth came under fire yet again in September, with the publication of data challenging the link between proteins called sirtuins and longer lifespan. Some saw the results as freeing the field to focus on other effects of sirtuins, such as regulating metabolism and responding to environmental stress. But Leonard Guarente, a sirtuin researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, who in 2001 published the original work linking sirtuins to longevity in worms, says the longevity link is real and that the new paper is just “a bump in the road”.

-

Faster than light?

OPERA claims to see faster-than-light neutrinos

Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, which is why most physicists are still sceptical about the results of an Italian experiment that suggested fundamental particles known as neutrinos can travel faster than light — the ultimate speed limit. The experiment, OPERA, is a neutrino detector at the Gran Sasso National Laboratory near L'Aquila. It saw a beam of neutrinos travelling 730 kilometres from CERN, Europe's particle-physics laboratory in Geneva, Switzerland, arrive 60 nanoseconds earlier than light would if travelling in a vacuum. Astonished physicists quickly looked for flaws in the analysis, but in November, OPERA released more data supporting its claim. Scientists are likely to remain doubtful until an independent experiment replicates the finding. MINOS at Fermilab in Batavia, Illinois, hopes to weigh in early in 2012.

• Particles break light-speed limit

• Faster-than-light neutrinos face time trial

• Neutrino experiment replicates faster-than-light finding

Image: CERN

-

Vaccines for Africa

Vaccine campaign to combat diarrhoea rolls out across Africa

Every year, more than one million children under the age of five die as a result of diarrhoea. It is the second-biggest killer in this age group, after pneumonia, and 40% of diarrhoea deaths are caused by rotavirus. But that horrific toll could soon fall, thanks to the first major roll-out of rotavirus vaccines in Africa, where half of rotavirus deaths occur. The programme was unveiled in September by the GAVI Alliance — formerly the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation — based in Geneva, Switzerland. The group hopes to immunize 50 million children against rotavirus in 40 of the world's poorest countries by 2015.

• Vaccine campaign to target deadly childhood diarrhoea

Image: GAVI/O. Asselin

-

Aboriginal genome

The aboriginal genome is published

For a field that relies on fossils that have lain undisturbed for tens of thousands of years, ancient human genomics is moving at breakneck speed. This year has seen a swathe of discoveries from last year’s publication of the genomes of Neanderthals and of an extinct human population from Siberia. And in September, a 90-year-old tuft of hair yielded the first complete genome of an Aboriginal Australian, a young man who lived in southwest Australia. He, and perhaps all Aboriginal Australians, the genome indicates, descend from the first humans to venture far beyond Africa more than 60,000 years ago, thousands of years before the ancestors of most modern Asians trekked east in a second migration out of Africa. "Aboriginal Australians are descendents of the first human explorers. These are the guys who expanded to unknown territory into an unknown world, eventually reaching Australia," says Eske Willerslev, a palaeogeneticist at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, who led the study.

• Ancient DNA reveals secrets of human history

• First Aboriginal genome sequenced

• Aboriginal genome analysis comes to grips with ethics

Image: M. Kolbe/Getty

-

Farewell Tevatron

Tevatron particle collider shuts down

After more than 25 years of colliding particles, the massive Tevatron accelerator at Fermilab in Batavia, Illinois, was switched off for good on 30 September. The collider helped to confirm the standard model of particle physics — it was where the top quark was found in 1995 — and it spent its final years restricting the possible mass range of the Higgs boson. Scientists are still analysing those data, while Fermilab is shifting to smaller-scale experiments.

• Fermilab faces life after the Tevatron

Image: R. Hahn/Fermilab

-

-

October

-

Patent

banEurope bans patents on human embryonic stem cells

European stem-cell researchers were dismayed after the European Court of Justice ruled that procedures using stem cells derived from human embryos cannot be patented. "This is the worst possible outcome and it's a disaster for Europe," said Oliver Brüstle of the University of Bonn, Germany, after learning that the court had felled his 1999 patent for a method of transforming human embryonic stem (ES) cells into neurons. “What hurt most personally was the accusation that scientists who work on human ES-cell lines are somehow immoral.” But some lawyers, funders and other researchers argued that there are other ways for companies and scientists who hope to commercialize ES cells to protect their inventions in Europe, and that a lack of patents could even speed up, rather than suffocate, innovation.

• European court bans patents based on embryonic stem cells

• European ban on stem-cell patents has a silver lining

• Stem cells: The cell division

Image: D. Scharf/Science Faction/Corbis

-

Malaria vaccine

GSK's vaccine for malaria gets mixed results in phase III trials

"World's first malaria vaccine works in major trial"; "Malaria vaccine almost here". To judge from media headlines, in October scientists made a big breakthrough in the long campaign to create a malaria vaccine, proving its effectiveness with interim results from a huge phase III clinical trial in Africa. But the RTS,S/AS01 vaccine, funded by pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline and the global PATH Malaria Vaccine Initiative, showed low efficacy against severe forms of malaria, disappointing some experts. Several leading researchers were critical of the unusual decision to publish partial trial data, and argued that the results raise questions about whether the vaccine can actually win approval.

• Malaria vaccine one step closer to approval

• Malaria vaccine results face scrutinyIm

Image: D. Poland/PATH Malaria Vaccine Initiative

-

Warming is real

Independent study affirms global warming

An independent analysis of the land-surface-temperature record concluded — if anyone was in doubt — that global warming is happening. The Berkeley Earth Surface Temperature (BEST) study, led by Richard Muller, a physicist at the University of California, Berkeley, mostly agreed with results from three teams that had previously studied data from land-temperature stations, although it used different statistical methods for the analysis. The BEST analysis was released on 20 October, but no part of it has yet been peer reviewed; the team is preparing to submit four papers to the Journal of Geophysical Research.

• Different method, same result: global warming is real

• Editorial: Scientific climate

Image: D. Tuffs/Getty

-

7 billion people

World’s population reaches 7 billion

According to a calculation based on surveys, censuses, probabilistic analyses, human sleuthing, expert opinion, heated academic debates and not a little guesswork, 31 October 2011 was the most likely day that the number of living humans would top 7 billion. On one level, that figure is incredible for the sheer momentum it represents: a full doubling of the planet's population since 1967, with current growth adding 200,000 people each day, and a nation larger than the size of France each year. But although the 6-billion mark was reached about 13 years ago, according to revised figures, it will take nearly 14 years to hit 8 billion. The comparison shows that population growth is decelerating; it is likely to level off at about 10 billion before the end of the century. Between now and then, the fastest growth will be in Africa, where fertility levels remain higher than anywhere else in the world. Population levels among industrialized countries, by contrast, will remain relatively constant.

Image: NASA

-

Dutch

fraudDiederik Stapel’s fraud revealed

When colleagues called the work of Dutch psychologist Diederik Stapel too good to be true, they meant it as a compliment. But an investigative report released on 31 October gave literal meaning to the phrase, detailing years of data manipulation and blatant fabrication by the prominent Tilburg University researcher. "We have some 30 papers in peer-reviewed journals where we are actually sure that they are fake, and there are more to come," says Pim Levelt, chair of the committee that investigated Stapel's work at the university. Stapel's eye-catching studies on aspects of social behaviour such as power and stereotyping garnered wide press coverage, but in September he was suspended over suspicions of research fraud. After the fraud was outlined, Stapel voluntarily surrendered his PhD, and retracted a 2011 study that suggested disorderly environments encourage discrimination — the first in what is likely to be dozens of retractions. A full report by investigating committees will not be finished until mid-2012.

• Report finds massive fraud at Dutch universities

• Dutch psychology fraudster issues first retraction

Image: Persbureau van Eijndhoven

-

-

November

-

Chinese kiss

China’s first space docking

Podcast interview: Asian space race

Nature Podcast: Clay Moltz discusses the Asian space race

You may need a more recent browser or to install the latest version of the Adobe Flash Plugin.China has notched up a string of high-profile space successes in recent years, but the best so far came in November with the docking in space of two unmanned orbiters, Shenzhou-8 and Tiangong-1. The delicate procedure was broadcast live on state television, in what media referred to as a ‘heavenly kiss’. It was a milestone in the country’s effort to build a manned space station, the Tiangong (‘Heavenly Palace’), by 2020. Two more missions, perhaps carrying astronauts, will follow in 2012. If the next stages of testing go to plan, China will launch further modules to be assembled into its heavenly palace.

-

Carbon taxes

Australia passes carbon tax

Australia emits more carbon per capita than any other country in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development — and arguments about whether to put a price on those emissions have been long and bitter. But by November, legislation to tax carbon dioxide emissions had passed its final barrier, the Senate. The tax of Aus$23 (US$23) per tonne for the country's top 500 emitters, starts from 1 July 2012 and will increase by 2.5% above inflation a year until an emissions-trading scheme replaces it in 2015.

• Australian climate scientists face death threats

• Australian politicians vote for carbon price

Image: Takver via Flickr under Creative Commons

-

Cell trials end

Geron pulls out of trial on human embryonic stem cells

It took Geron years and an infamous 21,000-page application to the US Food and Drug Administration to get permission to conduct a landmark clinical trial of a treatment for spinal cord injuries using human embryonic stem cells. But in November, the company based in Menlo Park, California, announced it was killing off its stem-cell programme so that it could focus on cancer therapies. “This is very unfortunate for the field,” says Robert Lanza, chief scientific officer of Advanced Cell Technology in Santa Monica, California, the only other embryonic stem-cell company with regulatory approval to conduct clinical trials in the United States. “It is a big deal. It certainly puts a lot of pressure on us to deliver now.”

Image: Redux/Eyevine

-

Mars missions

Russia’s Mars mission fails, but US Mars rover launches

It was the largest planetary mission in the history of space exploration, bearing Russia’s hopes of recapturing Soviet-era glory in Solar System exploration. But instead of rocketing off on a mission to return soil from the Martian moon Phobos, Phobos-Grunt is stuck in Earth orbit. Barring a miraculous restarting of its engines, it will make a fiery fall to Earth, probably by early January 2012 — and the Russian planetary programme could plunge along with it.

In contrast, NASA's Mars Science Laboratory, also known as Curiosity, is currently on its way to Gale crater on Mars. The 900-kilogram rover launched on 26 November, will spend the next nine months travelling to Mars and is scheduled to land in August 2012.

• Russia gets the red planet blues

• Curiosity on its way to Mars

Image: RIA Novosti

-

-

December

-

Twin

earth?Kepler mission discovers Earth-like planets

Podcast interview: exoplanets

Nature Podcast: Sara Seager discusses Kepler’s discovery of two Earth-like planets

You may need a more recent browser or to install the latest version of the Adobe Flash Plugin.In early December, NASA’s planet-hunting space telescope Kepler announced its first potentially habitable planet around a star like our Sun. Kepler-22b is not an Earth twin: at 2.4 times Earth's radius, it could be more like a gassy Neptune than a rocky planet. But it sits in a comfortably warm orbit from its host star, at temperatures similar to those experienced by Earth — although 184 parsecs (600 light years) away from us. Five days before Christmas, Kepler reached another major mission milestone: spotting a planet as small as Earth, along with another, Venus-sized, planet. Scientists were delighted with this feat of detection, but both planets orbit far too close to their parent star to be habitable.

• Kepler scores potentially habitable planet

-

Durban talks

Disappointing deal at Durban climate conference

After negotiations that ran into the early morning, politicians at the climate talks in Durban, South Africa, did manage to get global agreement over a new legally binding treaty to reduce carbon emissions — even persuading previously recalcitrant countries such as China and the United States to take part. That was the good news. The bad news is that the treaty will not be negotiated until 2015, and it would only come into force from 2020 — meaning that the ‘Durban Platform’ has effectively deferred action for a decade. The only extant global emissions treaty to set out legally binding emissions targets — the 1997 Kyoto Protocol — was set to run out in 2012, but will be extended by at least five years. The United States still refuses to ratify it, however, and developing nations are exempt; and Canada, unable to meet its Kyoto commitments, announced on 12 December that it would formally withdraw from the protocol.

• Durban maps path to climate treaty

• Nature special: Climate showdown in Durban

Image: A. Flak/Reuters

-

Higgs cornered

Large Hadron Collider sees hint of Higgs boson

Podcast interview: Higgs

Nature Podcast: Geoff Brumfiel discusses what CERN has announced about the Higgs boson

You may need a more recent browser or to install the latest version of the Adobe Flash Plugin.What a cliff-hanger. After gathering evidence from around 420 trillion proton–proton collisions in the Large Hadron Collider at CERN, Europe’s particle-physics lab near Geneva, physicists announced in December that they still couldn’t confidently state whether or not the Higgs boson exists — although they did identify its most likely hiding place, at a mass of around 125 gigaelectronvolts. Conclusion: more data needed. “Next year’s data should answer it without question,” says Bill Murray of the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory near Oxford, UK, who is leading the search for the Higgs by CERN’s ATLAS detector.

• Detectors home in on Higgs boson

• Nature’s Large Hadron Collider special

-

- Journal name:

- Nature

- DOI:

- doi:10.1038/nature.2011.9686

- Art: Kelly Buckheit Krause; Coding: Andrew Walker

Comments for this thread are now closed.