Abstract

Hypersensitivity pneumonia is a form of diffuse interstitial lung disease resulting from sensitization to an inhaled antigen. Clinical and radiological features are relatively nonspecific, overlapping significantly with other forms of diffuse interstitial lung disease. Establishing the diagnosis in the absence of lung biopsy is challenging and is heavily dependent on being able to identify a specific antigenic exposure. Lung biopsy is especially important in diagnosing hypersensitivity pneumonia in patients for whom no incriminating exposure has been elucidated. Surgical lung biopsies show a classical combination of findings in the majority of patients, which include an airway-centered, variably cellular chronic interstitial pneumonia, a lymphocyte-rich chronic bronchiolitis, and poorly formed non-necrotizing granulomas distributed mainly within the peribronchiolar interstitium. The bronchiolitis may include variable degrees of peribronchiolar fibrosis and hyperplasia of the bronchiolar epithelium (‘peribronchiolar metaplasia’), a characteristic but a nonspecific finding. In some patients, granulomatous inflammation may be lacking, resulting in a histological appearance resembling nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. Late-stage fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonia results in clinical, radiological, and histological findings that closely mimic usual interstitial pneumonia. The presence of established collagen fibrosis, especially when associated with architectural distortion in the form of honeycomb change, is associated with shorter survivals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Hypersensitivity pneumonia (-itis), also called extrinsic allergic alveolitis, is a diffuse interstitial lung disorder that results from sensitization to a variety of inhaled antigens, which are most commonly organic dusts or aerosols. Farmer's lung was the first described and is perhaps the best known example of this condition.1 Avian proteins (eg, bird fancier's or pigeon breeder's lung) are also a well established cause of hypersensitivity pneumonia. A large and growing number of syndromes have been described, and often are named according to the circumstances of exposure (Table 1). Offending agents are most commonly derived from thermophilic bacteria, molds, and various plant or animal proteins, although exposure to certain inorganic chemicals used in manufacturing workers can also result in hypersensitivity pneumonia-like syndromes.2, 3 More recently, non-tuberculous Mycobacteria has emerged as a cause of a hypersensitivity pneumonia-like syndrome in patients exposed to contaminated indoor hot tubs (ie, hot tub lung). Other forms of occupational lung disease resulting from inhalation of organic dusts, such as asthma, organic dust toxic syndrome, and chronic airway disease (eg, byssinosis), are unrelated to the diffuse interstitial disease referred to as hypersensitivity pneumonia.

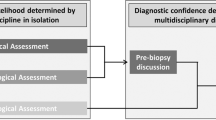

Criteria for diagnosis of chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia generally include an appropriate exposure history, subjective and objective evidence of lung disease temporally linked to antigen exposure, and the presence of serum antibodies directed against the suspected antigen.4, 5 Confirming the diagnosis is often difficult, however, because an incriminating exposure history is frequently elusive, and precipitating serum antibodies are unreliable. Given the absence of a diagnostic ‘gold-standard,’ recognition of characteristic histological findings in lung biopsies often has a pivotal role in diagnosis.6, 7, 8 This review focuses on the role of lung biopsy and the significance of histopathology in identifying and managing patients with hypersensitivity pneumonia.

Clinical features

Hypersensitivity pneumonia is often divided into acute, subacute, and chronic—or more simply, acute and chronic—forms. The terms have been inconsistently applied, reflecting significant overlap between these interrelated categories.5, 9 In general, acute hypersensitivity pneumonia is applied to patients suffering from a first attack, with symptom duration of less than 1 month. Subacute hypersensitivity pneumonia refers to patients with periodic symptoms for less than 1 year, and chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia refers to patients with progressive respiratory complaints for at least 1 year. Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia need not be preceded by acute disease, and only a small number of patients with acute disease develop chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia. More recently, evidence of fibrosis on lung biopsies or computed tomography (CT) scans has been used as a surrogate for identifying patients with chronic disease.10, 11, 12, 13

Acute hypersensitivity pneumonia follows exposure to relatively large doses of the responsible antigen and is the most easily recognized variant. Symptoms occur within 4–6 h of exposure, and include severe dyspnea and cough frequently associated with fever, chills, sweating, nausea, and anorexia.14 Weight loss may occur with frequent or severe attacks.14, 15 Symptoms subside 24–48 h after cessation of exposure and, in most patients, are followed by radiographic resolution over a period of days or weeks.

Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia results from intermittent exposure to the offending antigen and, in some patients, represents the cumulative effect of multiple acute episodes. The natural history of chronic hypersensitivity is sometimes punctuated by intermittent exacerbations temporally linked to antigen exposure. More commonly, patients present with a slowly progressive respiratory syndrome of insidious onset indistinguishable from other diffuse lung diseases, most importantly usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP)/idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).9, 16, 17, 18 Cough, often with associated dyspnea on exertion, is the most common presenting complaint. Fever usually accompanies respiratory symptoms during episodic exacerbations that follow antigen exposure.14, 15 Chest auscultation reveals fine inspiratory crackles in about 70% of patients. Digital clubbing is seen in only about 15% of patients. Laboratory studies show nonspecific abnormalities, including mild leukocytosis occasionally associated with mild peripheral eosinophilia. Serum levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme are normal, a finding that may have value in those patients for whom sarcoidosis is a competing consideration.19, 20 Pulmonary function studies demonstrate restricted lung volumes and a reduced carbon monoxide diffusing capacity. Affected patients may be unaware of the environmental exposure responsible for their respiratory symptoms, further complicating diagnosis. It is in this group of patients that lung biopsy frequently has a very important role in separating hypersensitivity pneumonia from idiopathic interstitial lung diseases.18

Radiological findings in chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia are not specific. High-resolution CT scans show a distinctive combination of ground glass opacities, small centrilobular nodules, and air trapping, characterized by mosaic attenuation in a subset of patients.9, 21 Emphysema is overrepresented in both smoking and non-smoking patients with chronic disease.9, 22 Associated honeycomb change is seen in about half of patients, and may be more common in those with pigeon breeder's lung. In patients with honeycomb change, the findings may be indistinguishable from UIP.11, 23

Recognition and diagnosis of chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia is especially challenging, because of the difficulty in identifying a temporal relationship between symptoms and a specific environmental exposure.9 Historically specific IgG-precipitating serum antibodies have been used as a diagnostic gold standard, but they are neither sensitive nor specific. Precipitins are markers of exposure, but have no role in pathogenesis, meaning that false positives are common. For example, precipitating antibodies are present in about 15% of asymptomatic farmers, and are nearly universal among asymptomatic pigeon breeders.18, 24 False negatives are also common due to variation in the quality of poorly standardized reagents and fluctuation in serum antibody levels over time.9, 24 Nonetheless, precipitating antibodies can be an important diagnostic adjunct in patients with known exposures, who also have episodic symptoms occurring 4–8 h after antigen exposure, inspiratory crackles, and weight loss.5 Inhalational provocation testing is another potentially useful diagnostic tool, but like serum precipitins, is dependent on first identifying a specific antigenic exposure temporally linked to the respiratory syndrome. Challenge studies are further limited by lack of standardized reagents and techniques, and are available only in specialized testing centers.4 Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) typically demonstrates a lymphocytosis with a predominance of CD8+ T cells, but these finding are not specific, and show significant variation depending on some extent on disease stage and the interval between antigen exposure and BAL testing.4

Prognosis for hypersensitivity pneumonia is variable. Antigen avoidance is the cornerstone of therapy and is often curative in patients, for whom a specific antigen source is identified, assuming the absence of established fibrotic lung disease at the time of diagnosis. Rapid recovery of pulmonary function is typical of acute hypersensitivity pneumonia, although rare fatal episodes have been documented.25 Corticosteroids are useful in accelerating the rate of recovery, but do not affect the long-term outcome, independent of eliminating antigenic exposure.26, 27 Lung function improves over a period of months and years, but abnormalities may persist in nearly half of patients.26, 27, 28 Disease-specific mortality rates in chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia range from 10 to nearly 30%. Repeated symptomatic attacks, older age, cigarette smoking, and the presence of established fibrosis and honeycomb change at the time of diagnosis, are associated with a more aggressive course.8, 10, 11, 12, 29, 30, 31, 32

Histopathological features

Lung biopsy is rarely necessary for diagnosis and management of patients with acute hypersensitivity pneumonia, and for that reason, pathological findings in this form of the disease are incompletely understood. Rare reports describe a patchy airspace filling process resembling bronchopneumonia, in which both neutrophils and eosinophils are present with an associated necrotizing small vessel vasculitis.25, 33

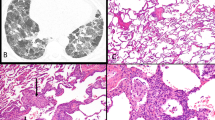

Lung biopsy often has a critical role in separating chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia from other forms of diffuse interstitial lung disease, especially in patients for whom no specific antigenic exposure is identified.6 Histological diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonia is predicated on recognition of a classical triad: 1) bronchiolocentric cellular chronic interstitial pneumonia, 2) chronic bronchiolitis, and 3) non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation affecting the peribronchiolar interstitium. Chronic interstitial pneumonia is the lesion most frequently described in surgical lung biopsies from patients with chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia.6, 7, 8, 10, 12, 14, 15 At low magnification, alveolar septa are expanded by an infiltrate of mononuclear inflammatory cells accentuated around bronchioles (Figure 1). The inflammatory infiltrate is composed mainly of lymphocytes with fewer plasma cells and histiocytes, and only occasional eosinophils and neutrophils (Figure 2). Epithelioid histiocytes predominate only focally, usually around the airways, and impart a subtle and vaguely granulomatous appearance to the inflammatory infiltrate. Well-formed granulomas are rare, except in patients with hot tub lung. Isolated multinucleated giant cells occur frequently in hypersensitivity pneumonia, and in some cases, may represent a striking feature (Figure 3). Giant cells often contain various nonspecific cytoplasmic inclusions such as Schaumann bodies, asteroid bodies, cholesterol clefts, and birefringent calcium salts.

Low-magnification photomicrograph (hematoxylin and eosin; × 40) of surgical lung biopsy from patient with hypersensitivity pneumonia resulting from bird exposure. Alveolar septa and peribronchiolar interstitium is expanded by a cellular infiltrate that is accentuated around the lumens of respiratory bronchioles (RB).

High-magnification photomicrograph (hematoxylin and eosin; × 400) of surgical lung biopsy from same hypersensitivity pneumonia patient illustrated in Figure 1, showing a lymphocyte-rich interstitial infiltrate. A single cluster of loosely organized epithelioid histiocytes (arrow) is present, resulting in a vaguely granulomatous appearance.

High-magnification photomicrographs (hematoxylin and eosin; × 400) of surgical lung biopsies from two different patients with hypersensitivity pneumonia, illustrating isolated multinucleated giant cells in peribronchiolar interstitium. One (a) shows cytoplasmic ‘cholestereol clefts,’ whereas the other shows calcified Schaumann bodies (b), both nonspecific findings that have no significance in terms of predicting likely antigenic exposure.

Chronic bronchiolitis is universal in hypersensitivity pneumonia, occasionally occurring in isolation without a concomitant interstitial pneumonia (Figure 4). The bronchiolitis is characterized by a variably dense infiltrate of mononuclear cells that expands the peribronchiolar interstitium with or without fibrosis. In it's most recognizable form, the bronchiolitis in hypersensitivity pneumonia is cellular, comprising predominantly lymphocytes, and includes the granulomatous features previously described. Associated lymphoid hyperplasia is common and takes the form of peribronchiolar lymphoid aggregates, often with associated secondary germinal centers (Figure 5).34 Organizing pneumonia, also referred to as bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia, accompanies the bronchiolitis in about half of the patients (Figure 6). In some biopsies, clusters of foamy alveolar macrophages fill the peribronchiolar air spaces, a form of microscopic obstructive pneumonia that is helpful in corroborating the presence of bronchiolitis and small airways dysfunction (Figure 7).

Low-magnification photomicrograph (hematoxylin and eosin; × 40) of surgical lung biopsy from patient with hypersensitivity pneumonia resulting from exposure to a pet bird. The biopsy shows only chronic bronchiolitis in which there is an exquisitely patchy, airway-centered interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes, with associated multinucleated giants cells. Many of the giant cells contain calcified Schaumann bodies (inset; × 200), a common but nonspecific finding that serves as a helpful diagnostic clue.

Hot tub lung is characterized by a granulomatous bronchiolitis that is histologically distinct from other forms of hypersensitivity pneumonia. Typically, the changes are limited to the airways and comprise not only the cellular peribronchiolar lymphocytic infiltrate seen in other types of hypersensitivity pneumonia, but also well-formed granulomas that reside within the airway lumens, rather than the peribronchiolar interstitium (Figure 8).35, 36, 37, 38 The well-formed granulomas are typically non-necrotizing, but may show small foci of central necrosis, more closely resembling granulomatous infection. Special stains will demonstrate acid-fast bacilli within the granulomas in about one fourth of biopsies; cultures of tissue or pulmonary secretions are usually positive for Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare.37

Lung biopsies from patients with well-established clinical diagnoses of hypersensitivity pneumonia occasionally show histological features that overlap with nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), with or without fibrosis. Katzenstein and Fiorelli's39 original description of NSIP included one patient in whom exposure to a pet parrot was cited as the etiology of his lung disease. It is unstated whether this patient might have been one of the five in whom loosely formed granulomas were present, but granulomatous features may be absent in as many as 30% of surgical lung biopsies from patients with hypersensitivity pneumonia. It is in the absence of peribronchiolar granulomatous inflammation that the features of hypersensitivity pneumonia may be indistinguishable from otherwise idiopathic NSIP.7, 10, 12, 40, 41 Patients with hypersensitivity pneumonia in whom surgical lung biopsies show NSIP have a chronic interstitial pneumonia in which there is relatively uniform alveolar septal expansion by chronic inflammation with or without fibrosis. NSIP with fibrosis is distinguished from UIP by the absence of either a ‘patchwork’ distribution of fibrosis, or architectural distortion in the form of scarring or honeycomb change.42

Histopathological clues to hypersensitivity pneumonia as a potential etiology in patients with a lung biopsy diagnosis of NSIP include bronchiolocentric accentuation of the inflammation, and a pattern of peribronchiolar fibrosis and bronchiolar epithelial hyperplasia termed peribronchiolar metaplasia.7, 10, 43 Peribronchiolar metaplasia is seen in as many as half of the surgical lung biopsies from patients with hypersensitivity pneumonia (Figure 9), and is a universal finding at autopsy.7, 43, 44 Peribronchiolar metaplasia has also been reported as an isolated histopathological manifestation of hypersensitivity pneumonia.10 Peribronchiolar metaplasia is not specific, however, in that it occurs in other settings; therefore, the presence of peribronchiolar metaplasia alone is insufficient to establish a diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonia with certainty in the absence of other supportive evidence.

Intermediate-magnification photomicrograph (hematoxylin and eosin; × 100) demonstrating peribronchiolar metaplasia in a patient with hypersensitivity pneumonia. Peribronchiolar interstitium is expanded by a combination of chronic inflammation and fibrosis with associated hyperplasia of columnar bronchiolar epithelial cells.

Advanced stage chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia is associated with fibrosis and architectural distortion that mimics the radiological and histological features of UIP.7, 10, 12, 41, 44 Histological findings may include patchy fibrosis, peripheral subpleural honeycomb change, and fibroblast foci, a combination of findings typical of UIP (Figure 10). In a comparison of autopsy findings in patients with UIP/IPF and hypersensitivity pneumonia, honeycomb change affected the lower lobes in all of them, and the upper lobes in over 80% of patients in both the groups. The main difference was that honeycomb change had a predominantly upper lobe distribution only in patients with hypersensitivity pneumonia, although this occurred in less than half.44 The key to separating late-stage hypersensitivity pneumonia from UIP in surgical lung biopsies is recognition of the cellular, granulomatous bronchiolitis typical of hypersensitivity pneumonia away from the areas of fibrosis (Figure 11). Peribronchiolar metaplasia occurs more frequently and is more widely distributed in hypersensitivity pneumonia compared with UIP/IPF, but is common in both and therefore cannot be used by itself as a discriminating histological feature.43, 44

Higher-magnification photomicrograph (hematoxylin and eosin; × 200) from central area of field illustrated in Figure 10, showing peribronchiolar lymphocytic infiltrate (‘bronchiolitis’) with a single multinucleated giant cell largely obscured by cytoplasmic calcifications. The presence of a lymphocytic bronchiolitis with granulomatous features typical of hypersensitivity pneumonia is the key in separating usual interstitial pneumonia/idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (UIP/IPF) from late, fibrotic-stage hypersensitivity pneumonia.

Prognostic significance of histopathological features

Several studies have demonstrated a relationship between histology and survival, although all are retrospective observational case-based studies, and therefore subject to bias. 7, 8, 10, 31, 41 In a review of 72 patients referred to the National Jewish Medical and Research Center, who underwent surgical lung biopsy, fibrosis was defined as either honeycomb change or alveolar septal expansion by mature collagen involving at least 5% of the sampled tissue. Using this definition, 46 (63.9%) patients had fibrotic disease. Median survival in patients with fibrotic disease was 7.1 years compared with greater than 20.9 years in the 26 patients who lacked fibrosis. Indeed, dyspnea score and biopsy fibrosis were the only statistically significant predictors of mortality in this large study. Perez-Padillia et al31 previously showed that a biopsy diagnosis of UIP in patients suspected of having chronic pigeon breeders’ lung had a survival that was indistinguishable from patients with UIP/IPF, and significantly worse compared with patients with histological findings more typical of chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia. Smaller studies for which statistical analysis is less compelling have consistently shown that fibrotic disease resembling UIP in patients thought to have chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia is associated with shorter survivals compared with patients with the classical histological features previously described.7, 10, 12, 41 The unfavorable prognostic impact of fibrosis extends to patients for whom the histological findings more closely mimic fibrotic NSIP or peribronchiolar metaplasia, although the numbers are considerably smaller (Figure 12).10, 12

Bar graph illustrating the association between mortality and lung biopsy findings in patients with hypersensitivity pneumonia collected from multiple published studies.7, 10, 12, 41 Abbreviations: HSP, classical hypersensitivity pneumonia; BOOP, organizing pneumonia; C-NSIP, cellular nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; F-NSIP, fibrotic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia; PBM, peribronchiolar metaplasia.

Summary

Lung biopsy can have a key role in recognizing patients with chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia and hinges on recognition of a characteristic combination of interstitial pneumonia, bronchiolitis, and granulomatous inflammation. Late-stage disease is associated with fibrosis that may mimic other forms of fibrotic lung disease, including most importantly UIP. The available evidence suggests that fibrosis portends a worse prognosis, although this has not been prospectively validated.

References

Campbell J . Acute symptoms following work with hay. Br Med J 1932;2:1143–1144.

Baur X . Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (extrinsic allergic alveolitis) induced by isocyanates. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1995;95:1004–1010.

Nakashima K, Takeshita T, Morimoto K . Occupational hypersensitivity pneumonitis due to isocyanates: mechanisms of action and case reports in Japan. Ind Health 2001;39:269–279.

Fink JN, Ortega HG, Reynolds HY, et al. Needs and opportunities for research in hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:792–798.

Lacasse Y, Selman M, Costabel U, et al. Clinical diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;168:952–958.

Coleman A, Colby TV . Histologic diagnosis of extrinsic allergic alveolitis. Am J Surg Pathol 1988;12:514–518.

Trahan S, Hanak V, Ryu JH, et al. Role of surgical lung biopsy in separating chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia from usual interstitial pneumonia/idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: analysis of 31 biopsies from 15 patients. Chest 2008;134:126–132.

Vourlekis JS, Schwarz MI, Cherniack RM, et al. The effect of pulmonary fibrosis on survival in patients with hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am J Med 2004;116:662–668.

Glazer CS, Rose CS, Lynch DA . Clinical and radiologic manifestations of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. J Thorac Imaging 2002;17:261–272.

Churg A, Sin DD, Everett D, et al. Pathologic patterns and survival in chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:1765–1770.

Hanak V, Golbin JM, Hartman TE, et al. High-resolution CT findings of parenchymal fibrosis correlate with prognosis in hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Chest 2008;134:133–138.

Ohtani Y, Saiki S, Kitaichi M, et al. Chronic bird fancier's lung: histopathological and clinical correlation. An application of the 2002 ATS/ERS consensus classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Thorax 2005;60:665–671.

Sahin H, Brown KK, Curran-Everett D, et al. Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis: CT features comparison with pathologic evidence of fibrosis and survival. Radiology 2007;244:591–598.

Dickie H, Rankin J . Farmer's Lung. An acute granulomatous interstitial pneumonitis occurring in agricultural workers. JAMA 1958;167:1069–1076.

Emanuel D, Wenzel F, Bowerman C, et al. Farmer's Lung. Clinical, pathologic and immunologic study of twenty-four patients. Am J Med 1964;37:392–401.

Yoshizawa Y, Ohtani Y, Hayakawa H, et al. Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis in Japan: a nationwide epidemiologic survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999;103:315–320.

Hanak V, Golbin JM, Ryu JH . Causes and presenting features in 85 consecutive patients with hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Mayo Clin Proc 2007;82:812–816.

Morell F, Roger A, Reyes L, et al. Bird fancier's lung: a series of 86 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2008;87:110–130.

McCormick JR, Thrall RS, Ward PA, et al. Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme levels in patients with pigeon-breeder's disease. Chest 1981;80:431–433.

Tewksbury DA, Marx Jr JJ, Roberts RC, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme in farmer's lung. Chest 1981;79:102–104.

Silva CI, Churg A, Muller NL . Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: spectrum of high-resolution CT and pathologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007;188:334–344.

Erkinjuntti-Pekkanen R, Rytkonen H, Kokkarinen JI, et al. Long-term risk of emphysema in patients with farmer's lung and matched control farmers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;158:662–665.

Silva CI, Muller NL, Lynch DA, et al. Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis: differentiation from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia by using thin-section CT. Radiology 2008;246:288–297.

Cormier Y, Belanger J . The fluctuant nature of precipitating antibodies in dairy farmers. Thorax 1989;44:469–473.

Barrowcliff DF, Arblaster PG . Farmer's lung: a study of an early acute fatal case. Thorax 1968;23:490–500.

Kokkarinen JI, Tukiainen HO, Terho EO . Effect of corticosteroid treatment on the recovery of pulmonary function in farmer's lung. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992;145:3–5.

Monkare S, Haahtela T . Farmer's lung--a 5-year follow-up of eighty-six patients. Clin Allergy 1987;17:143–151.

Erkinjuntti-Pekkanen R, Kokkarinen J, Tukiainen H, et al. Long-term outcome of pulmonary function in farmer's lung: a 14 year follow-up with matched controls. Eur Respir J 1997;10:2046–2050.

Braun SR, doPico GA, Tsiatis A, et al. Farmer's lung disease: long-term clinical and physiologic outcome. Am Rev Respir Dis 1979;119:185–191.

Vourlekis JS, Schwarz MI, Cherniack RM, et al. The effect of pulmonary fibrosis on survival in patients with hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am J Med 2004;116:662–668.

Perez-Padilla R, Salas J, Chapela R, et al. Mortality in Mexican patients with chronic pigeon breeder's lung compared with those with usual interstitial pneumonia. Am Rev Respir Dis 1993;148:49–53.

Ohtsuka Y, Munakata M, Tanimura K, et al. Smoking promotes insidious and chronic farmer's lung disease, and deteriorates the clinical outcome. Intern Med 1995;34:966–971.

Ghose T, Landrigan P, Killeen R, et al. Immunopathological studies in patients with farmer's lung. Clin Allergy 1974;4:119–129.

Perez-Padilla R, Gaxiola M, Salas J, et al. Bronchiolitis in chronic pigeon breeder's disease. Morphologic evidence of a spectrum of small airway lesions in hypersensitivity pneumonitis induced by avian antigens. Chest 1996;110:371–377.

Embil J, Warren P, Yakrus M, et al. Pulmonary illness associated with exposure to Mycobacterium-avium complex in hot tub water. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis or infection? Chest 1997;111:813–816.

Grimes MM, Cole TJ, Fowler III AA . Obstructive granulomatous bronchiolitis due to Mycobacterium avium complex in an immunocompetent man. Respiration 2001;68:411–415.

Hanak V, Kalra S, Aksamit TR, et al. Hot tub lung: presenting features and clinical course of 21 patients. Respir Med 2006;100:610–615.

Khoor A, Leslie KO, Tazelaar HD, et al. Diffuse pulmonary disease caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria in immunocompetent people (hot tub lung). Am J Clin Pathol 2001;115:755–762.

Katzenstein AL, Fiorelli RF . Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia/fibrosis. Histologic features and clinical significance. Am J Surg Pathol 1994;18:136–147.

Vourlekis JS, Schwarz MI, Cool CD, et al. Nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis as the sole histologic expression of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am J Med 2002;112:490–493.

Hayakawa H, Shirai M, Sato A, et al. Clinicopathological features of chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Respirology 2002;7:359–364.

Katzenstein AL, Mukhopadhyay S, Myers JL . Diagnosis of usual interstitial pneumonia and distinction from other fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Hum Pathol 2008;39:1275–1294.

Fukuoka J, Franks TJ, Colby TV, et al. Peribronchiolar metaplasia: a common histologic lesion in diffuse lung disease and a rare cause of interstitial lung disease: clinicopathologic features of 15 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:948–954.

Akashi T, Takemura T, Ando N, et al. Histopathologic analysis of sixteen autopsy cases of chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis and comparison with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis/usual interstitial pneumonia. Am J Clin Pathol 2009;131:405–415.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Myers, J. Hypersensitivity pneumonia: the role of lung biopsy in diagnosis and management. Mod Pathol 25 (Suppl 1), S58–S67 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2011.152

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2011.152

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Clinico- pathologic presentation of hypersensitivity pneumonitis in Egyptian patients: a multidisciplinary study

Multidisciplinary Respiratory Medicine (2017)

-

Biomarkers in interstitial lung disease: moving towards composite indexes and multimarkers?

Current Pulmonology Reports (2015)

-

Management of hypersensivity pneumonitis

Clinical and Translational Allergy (2013)

-

Diagnostic approach to interstitial lung disease

Current Respiratory Care Reports (2012)