Abstract

Purpose:

With the increasing interest in apolipoprotein E (APOE) genetic testing to estimate the risk of developing late-onset Alzheimer disease, new educational tools are needed to help people make the best decision for themselves about whether to undergo this test. This study evaluated an online tool to assist in this decision process.

Methods:

A prototype decision aid was studied in a two-part survey that collected data from participants before and after they examined the decision aid. Both surveys had multiple-choice options and opportunities for open-ended responses, yielding quantitative and qualitative information. The responses before and after use of the aid were compared for each participant.

Results:

A total of 1,262 individuals completed both surveys. The overall effectiveness of the decision aid was shown by three measures: 94% found the decision aid very helpful or somewhat helpful; general knowledge was increased; and some people changed their minds about APOE genetic testing, with 35% shifting to a higher likelihood of undergoing the test and 20% to a lower likelihood. Suggestions for improvements were noted and incorporated into the online tool.

Conclusion:

This decision aid can provide useful educational assistance to many individuals as they consider APOE genetic testing as well as facilitate further discussions with their health-care providers.

Genet Med advance online publication 03 November 2016

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although it is widely accepted that genetic testing provides useful information, the literature shows that such testing can also cause emotional distress, adversely affect family members, and raise worries about possible misuse by insurers and employers.1,2 In the past, decisions about such tests were made in consultation with genetic counselors and other genetic professionals. Increasingly, however, genetic tests, especially those for complex disorders such as Alzheimer disease, are being made available in doctors’ offices and on the Web through direct-to-consumer (DTC) testing companies—situations in which there is often inadequate time or opportunity for meaningful discussion or preparation.

The e4 allele of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene has been shown to be a risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer disease.3,4,5,6 Having one e4 allele raises a person’s lifetime risk to 25–40%. Having two copies raises the risk to approximately 55%. However, even for people with two e4 alleles in their genetic signature, it is not certain that the disease will develop; conversely, many people without this allele do develop Alzheimer disease.7

APOE testing is available both as a single genetic test and as part of a package of tests for estimating cardiovascular disease risk. It is also available through DTC companies, bundled together with genetic tests for other health conditions or for genealogy. Prominent medical and genetic professional groups have recommended against APOE testing. They emphasize that (i) the test does not identify those who will definitely develop the disease and (ii), for those found to be at higher risk, there are no current medical interventions that can reduce the symptoms or prevent the disease.8,9,10,11 A recent consensus statement reaffirms this recommendation, with the proviso that if genetic testing is sought nonetheless, it should be accompanied by genetic counseling and psychosocial assessment.12

The NIH’s REVEAL (Risk Evaluation and Education for Alzheimer’s disease) studies examined the effects of disclosure of APOE status to asymptomatic adults with an affected parent.13,14 They concluded that disclosure of APOE status caused only temporary and minor distress to those found to have e4 genes and lowered symptoms of depression and anxiety in those found to have no e4 gene. However, potential participants received substantial genetic counseling prior to entering these studies and were excluded if they showed signs of depression or anxiety. In more usual situations in which genetic testing is performed with little or no counseling, there have been reports of adverse effects in those receiving news of being at higher risk for Alzheimer disease.15,16

More than 5 million people in the United States have been diagnosed with late-onset Alzheimer disease. Millions more are likely to be affected in the near future as the number of people aged 65 and older increases.17 There is concern that the increasing demand for APOE genetic testing18 will overwhelm counseling and educational resources.19 In addition, participation in some Alzheimer prevention studies calls for genetic testing to select those at highest risk.

There have been calls for new and validated educational tools that can be used to assist those making decisions about whether to undergo APOE testing and other forms of susceptibility-gene testing. Such tools could also serve as the basis for further decision-making during consultations with doctors.20,21,22 We have developed an online educational tool and decision aid to help individuals considering APOE genetic testing. This tool was first endorsed by two focus groups and a panel of medical and genetic professionals. To be fully useful, however, any educational tool needs to be evaluated by consumers considering genetic testing. We report here on such a study of our Alzheimer disease genetic-test decision aid. We describe the effectiveness of the decision aid and the improvements made in response to suggestions provided by the users.

Materials and Methods

Prototype online decision aid

Development of the decision aid was based on a framework of four general questions that people should consider as they make a decision about whether to pursue genetic testing. These four questions emerged from the analysis of ethnographic interviews carried out in a study of people who were facing a genetic-testing decision for one of several complex disorders, including Alzheimer disease.23 The questions are (1) is there a family history?, (2) will the test give useful information?, (3) is this the right time for testing?, and (4) do the advantages of obtaining the information outweigh the disadvantages?

The material was presented following standards recommended for decision aids.24 The average reading level for the prototype is eighth to ninth grade.25

Question 4 calls for each person to consider personal values, family realities, and social-level concerns. For example, while at the personal level APOE testing can help with planning for the future, it can also bring on psychological distress. At the family level, testing can alert others to their risk but it can also create tension and rifts within the family. At the social level, there is the possibility of participation in a research study but also the possible loss of genetic privacy and misuse of the test results by employers and insurance companies. To help clarify these values-laden issues, a series of short dramatized vignettes was developed in which actors show the advantages and disadvantages of APOE testing using extended quotes taken from the ethnographic interviews. The original vignettes were reviewed by a focus group (n = 9) that found them very helpful in allowing value components to be recognized.26 One of the major suggestions for improvement was to have individual actors present values and issues arising at the personal level but to have pairs of actors discuss the pros and cons of issues arising at the family and social levels. The videos were revised to incorporate those suggestions.

A concluding section provides a summary indicating where concerns, if any, were expressed about genetic testing. All summaries, even for those who had answered “yes” to each question, recommended consultation with a medical or genetic professional. Here, general concerns raised by the questions, as well as concerns specific to each individual, could be further addressed. The tool gave no summary recommendation for or against genetic testing.

Validation study

The prototype online decision aid for APOE genetic testing was evaluated in a two-part before-and-after repeated-measures survey conducted by the Virginia Tech Center for Survey Research and approved by the Virginia Tech Institutional Review Board (14–381). Prospective participants were directed to either an online site or a dedicated telephone number where they received a description of the study along with consent information. Those who chose to participate were given the URL for the online study site. Consent to participate was signified by completion of the surveys. In survey 1, data were collected from participants prior to their examination of the decision aid. In survey 2, data were collected from these same participants 1 week after they had examined the decision aid. Both surveys had multiple-choice, including Likert-scale, questions, as well as opportunities for open-ended responses, yielding quantitative and qualitative information. Each participant was provided a unique survey link that showed respondent e-mail addresses (which were each assigned a random tracking number) to be used in the follow-up for participants for survey 2 data collection. This permitted the before-and-after (repeated measure) responses of each participant to be compared, thereby eliminating variation among subjects by allowing each participant to serve as his or her own control. E-mail addresses were kept separate and were never linked to the data set. All e-mail addresses were deleted from the system and destroyed when the data-collection portion of the study closed. There was no financial or other compensation for participants (samples of both surveys can be found in the Supplementary Methods and Procedures online).

Participants

A multipronged effort was undertaken to call the study to the attention of potential participants. Information was sent to regional support groups, adult day-services centers, community organizations, state agencies, and medical centers. The study was listed with online registries that inform people about Alzheimer disease research protocols. These included the Alzheimer’s Association TrialMatch website, the Alzheimer’s Prevention Registry of the Banner Health Institute (Phoenix, AZ), and the ADEAR Center (NIH) clinical trial database. Given the nature of these recruitment efforts, it is likely that many of the participants were already well informed either from direct personal experience or from their own efforts to seek information on the Internet.

Data analysis

All analytics were performed using JMP software.27 P values28 for statistical significance were calculated as follows for nominal and ordinal multiple-choice questions: for differences among multiple choices for individual questions, Pearson’s chi-squared goodness-of-fit test for homogeneity of frequencies was used;28 for relations among pairs of questions, Pearson’s chi-squared contingency table analysis was used;28 for after-minus-before comparisons of Likert-scale responses, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used;29 for comparisons among series of Likert-scale questions, Friedman’s test was used.30

One “placebo/control” question was included in surveys 1 and 2 to check for Hawthorne-type effects, i.e., that knowledge of being in a study may possibly alter participants’ behavior or assessments.31 This question dealt with “financial consequences” associated with genetic testing. Because this topic was not addressed in the tool, no change between surveys 1 and 2 would be expected.

Qualitative data from open-ended questions were obtained by examining all the written responses to specific survey questions. All such responses were coded to identify major themes and categories within each theme. Responses within each category were prioritized by the number of comments received.

Results

Demographics

Approximately 2,850 inquiries were received. Of these, 1,747 participants completed survey 1 of the study, and 1,262 participants completed the study by viewing the decision aid prototype and responding to survey 2. Of those who completed both surveys, 86% were female and 14% were male. Ages ranged from 22 to 87 years old, with a mean age of 54.5 and a median age of 56 years. More than 90% of the participants self-identified as white.

Of the 1,262 participants, 81% had someone in the family who had been diagnosed with Alzheimer disease and 52% had been a care provider for someone with Alzheimer disease. Among those with an Alzheimer disease diagnosis within the family, 60% had been care providers; among those without a family history, only 17% had been care providers. Almost all participants (97%) indicated that they had health insurance.

As might be expected for an online study, nearly all participants (97%) indicated that they were comfortable using computer-based materials. There were no statistically significant differences when participants older than age 60, who might be thought of as less at ease with such materials, were compared with younger age groups. The time it took to review the decision aid averaged 20 minutes, with 80% of the participants completing their review within 10–35 minutes.

Overall effectiveness of the decision aid

A number of measures were used to assess the overall effectiveness of the decision aid for APOE genetic testing. The first measure was a direct query about the helpfulness of the aid. In response, 34% of the participants rated it as being very helpful and 60% rated it somewhat helpful, for an overall positive rating of 94%. Only 6% indicated that it was not very helpful or not at all helpful. In a related query, 93% of respondents reported that they would recommend this educational tool to others considering APOE testing.

Written comments in response to optional open-ended questions expanded on these choices. Of those who wrote about why they found the decision aid “very helpful” (374 responses), the major comments indicated that they found it balanced as well as clear and user-friendly. They also indicated that they appreciated having the decision broken down into useful components. Of those who found the decision aid to be “somewhat helpful” (619 responses), the balance and the value of the new information provided was also cited. For some of them, however, there was a desire for a definitive recommendation regarding genetic testing, which the tool does not provide. Of the group who found the tool “not very helpful” or “not at all helpful” (68 responses), the major reason given was that they felt themselves well informed prior to examining the tool.

The “placebo/control” question to estimate Hawthorne-type effects yielded only a very small, clinically unimportant change (0.08 Likert units on a 4.0-point Likert scale) at the margin of statistical significance. Thus, any such effect was too small to appreciably impact the results.

Another measure of effectiveness is whether there is an increase in general knowledge. Respondents were asked to what extent they are now familiar with the factors that influence risk for developing Alzheimer disease. Of the 1,221 volunteers who answered before and after viewing the decision aid, 47% reported no change in familiarity, 49% reported an increase in familiarity, and only 4% reported a decrease in familiarity. The average increase in familiarity was 0.55 Likert-scale units (P < 0.0001).

With regard to the meaning of APOE genetic-test results, the before-and-after comparison showed a dramatic educational effect for one subset of respondents. This subset (203; 17%) consisted of respondents who initially indicated that they did not know what to expect (122; 10%) or who mistakenly believed that the results of APOE testing would definitely reveal, with certainty, whether they would develop Alzheimer disease (81, 7%). After examining the decision aid, most of these same individuals (148; 73%) came to understand that the results of genetic testing would reveal only whether their risk is higher than average but would not provide certainty. The rest (83%) of the 1,221 respondents already knew that the test results would not provide certainty. This encouraging figure is not surprising given that recruitment efforts largely reached people who were already actively seeking information about genetic testing.

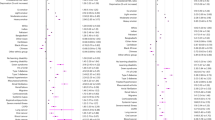

Another measure of effectiveness is whether the decision aid enables people to more knowledgably reconsider previously held views that may have been based on partial or incorrect information. Drawing again on the before-and-after tracking feature, the data in Figure 1 show that more than half the participants changed their perceived likelihood of pursuing testing during the next year, with 35% shifting to greater likelihood and 20% shifting to a lower likelihood. Figure 1 shows a coherent and sensible “triangular” pattern in the change in perceived likelihood after using the tool. That is, in either direction, positive or negative, smaller changes are more prevalent than larger changes.

Difference (after viewing the decision aid minus before viewing it, in Likert-scale units) in “How likely are you to get genetic testing for Alzheimer’s disease in the next year?” For this question, the Likert-scale units were −2 = “Not at all likely,” −1 = “Somewhat unlikely,” 0 = “Haven’t really formed an opinion yet,” +1 = “Somewhat likely,” and +2 = “Very likely.” Thus, a difference of +4 Likert units is an increase in perceived likelihood from −2 = “Not at all likely” before viewing the decision aid to +2 = “Very likely” after viewing it. A difference of +3 means an increase from −2 to +1 or from −1 to +2. A negative difference (i.e., a change of −1,−2, −3, or −4) indicates a decrease in likelihood. Shown are the results for the 95% of respondents who did not previously undergo APOE testing (n = 1,174).

Although Figure 1 shows the overall pattern of change, Figure 2 goes deeper by showing the specific pattern of change for each level of initial likelihood of testing. The triangular pattern seen in Figure 1 occurs for each level of initial perceived likelihood. Finally, Figure 2 shows that for those not in the two extreme positions (“very likely” or “not at all likely”), change occurs in both directions.

The use of vignettes for presenting value components involved in a genetic-testing decision

One of the challenges in making a genetic-testing decision is evaluating the advantages and disadvantages that result from undergoing such testing. This examination calls for each person to draw on his or her own personal values and experiences as well as on family realities and social-level concerns.

As an aid in promoting clarification of individual values, the prototype relied on short, dramatized vignette modules. These vignettes provided human faces and voices of people explaining their reasons for and against undergoing genetic testing for predisposition to Alzheimer disease. Survey questions were designed to evaluate this values-clarification component. Survey respondents were also able to add personal comments. Many took the opportunity to comment specifically on the vignette modules.

More than half of the respondents (57%) indicated that the vignettes were either a major influence (23%) or somewhat of an influence (34%) as they pondered a decision. Others, approximately 44%, felt that they were only a minor influence (26%) or had no influence at all (18%). The respondents’ written comments helped to clarify these differing assessments. Analysis of these qualitative data revealed that for some, the vignette component was a very important means of helping them identify and align their values before making a decision. Here is a brief sampling of such comments:

I appreciated especially the different ideas being presented by the actors in such a realistic way that I could feel which point of view most resonated with me—well done!

I loved the different opinions and thoughts in the videos regarding the decision to undergo genetic testing. There was a variety of people in different age groups and races and I loved their opinions and concerns. They mimic my own.

It allowed me to think of things that I would not have thought of with regards to getting tested, such as, is this a good time in my life to know this information, how would it affect me to know, how would it affect my family, etc. It brought up points I didn’t think about.

It gave the pros and cons of aspects that test results would affect...insurance, family, planning concerns—it stimulated detailed thought in each area, thoughts which might not occur to people, i.e., how would other siblings and children be affected psyhologically [sic] by results.

Among the participants who did not find the videos helpful, there was a clearly stated preference for text-based presentations.

I didn’t care for the video segments. They felt contrived and gave me information that I would rather have read.

It spurred me to consider other factors that I hadn’t thought of around genetic testing, but the videos weren’t an ideal way to present information to me. I found the actors distracting and would prefer to have the option to read case studies or narrative.

I also didn’t like the use of videos—I did not watch them. I would prefer to be able to scan textual information without having to take the time to watch a video.

I know something of the impact might be lost, but I would suggest including an option to read text instead of watching videos. This would help people with slow internet connections and those who only have access to public computers and aren’t comfortable having sound play.

In sum, for many participants, the vignettes were seen as extremely helpful in identifying the values that come into play with genetic testing. The vignettes assisted them with their own values-clarification efforts. Others, however, with a different learning style or who were using the tool in public settings where sound was a problem, indicated a strong preference for receiving this information in text-form only.

Modes for future genetic testing

Only a few respondents (126) indicated having had any experience with genetic testing prior to their use of the decision aid. Of these, 52% had undergone testing in a medical setting and 33% had testing performed on their own by a DTC company. Of the 890 respondents who answered regarding their choice of testing mode after examining the prototype, the preference for having APOE testing under the auspices of the medical community was 72% and the preference for having testing via a DTC company was 20%. Of those who had already undergone DTC genetic testing, half indicated that they would continue to use the DTC mode.

Suggestions for improvements

Participants were asked for suggestions for improving the decision aid. More than 700 comments of all kinds were received. Approximately one-quarter of the comments stated that there were no revisions to recommend. The rest made suggestions that fell into three major categories, as shown in Table 1 .

Discussion

Overall, these analyses support the view that the online decision aid was an effective educational tool. It enabled people to learn about APOE genetic testing and it was useful to them as they considered (or, in some cases, reconsidered) their genetic-testing decisions. Given the limited number of genetic counselors in the United States and the limitations of time in any doctor’s office visit, there is a need for alternative mechanisms for presenting genetic information in an easily accessible and balanced manner. Online tools, such as this one, can help meet this need.

Personal, family, and societal values factor into genetic-testing decisions. This study has shown that a novel feature of this decision aid—the use of short, dramatized vignette modules—can be an effective additional means of sorting through and clarifying values issues for a sizeable group of participants. However, based on the feedback received, it is evidently important to also use text-based educational methods so that the values aspect of the genetic-testing decision can be appreciated by users more attuned to text only. A text option also makes it possible to use the decision aid in settings where sound is unwelcome, such as libraries or doctors’ offices.

By reaching out for the advice of consumers, educational materials can be revised to improve their usefulness. Table 1 shows the changes made in an effort to benefit from the recommendations that were received. The average reading level (eighth to ninth grade) did not change. A printout option was also added to the tool’s summary page. It provides a document that can be shared with health-care providers.

Professional organizations have issued consensus statements criticizing the use of DTC genetic testing and calling for the involvement of genetic professionals.32,33 Although overall interest in using DTC testing was reduced after using the decision aid, it still remains the preferred choice of a significant subset (20%) of the survey participants, especially those who had undergone DTC testing previously. Given that 40% of those who originally indicated that they were “likely” to undergo genetic testing changed toward reduced interest after using the decision aid, as did 25% of those who originally were “somewhat likely” to seek testing, this online tool could be of use to individuals who prefer to bypass the medical community when they consider testing.

Some limitations of this study should be noted. First, in general, the participants recruited were computer-literate individuals who were motivated to explore Alzheimer disease online. Less knowledgeable or motivated members of the general population may need different formats or methods of engagement. Second, the participants were mostly female and Caucasian. Although not representative of the general population, this group is consistent with the demographic profile of those who enroll in the research registries and who participate in the support groups reached during the recruitment process. They also match the profile, as determined in the REVEAL studies,19 of those most likely to seek APOE testing. It is also worth noting that the prevalence of Alzheimer disease is significantly higher for women than for men.4 Another limitation is that, although no substantial differences were found due to sex or heritage group, because of the dearth of males and nonwhite participants, this study might not have been able to detect such differences. Finally, any decision aid, no matter how well validated, needs to be updated periodically in order to incorporate new research findings and advances in modes of treatment and prevention, as well as new recommendations put forth by professional groups.

This tool is now freely available on a dedicated website.34 Validated educational tools can play an important role in helping this new age of genomic medicine yield the greatest amount of benefit with the least harm.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Quaid KA, Morris M. Reluctance to undergo predictive testing: the case of Huntington disease. Am J Med Genet 1993;45:41–45.

Zallen DT. Does it Run in the Family? A Consumer’s Guide to DNA Testing for Genetic Disorders. Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, 2008.

Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, et al. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science 1993;261:921–923.

Breitner JC, Wyse BW, Anthony JC, et al. APOE-epsilon4 count predicts age when prevalence of AD increases, then declines: the Cache County Study. Neurology 1999;53:321–331.

Christensen KD, Roberts JS, Royal CD, et al. Incorporating ethnicity into genetic risk assessment for Alzheimer disease: the REVEAL study experience. Genet Med 2008;10:207–214.

Seshadri S, Wolf PA. Lifetime risk of stroke and dementia: current concepts, and estimates from the Framingham Study. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:1106–1114.

Bird TD. Alzheimer disease overview. 23 October 1998 (updated 24 September 2015). In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al.(eds). GeneReviews. University of Washington: Seattle, WA, 1993–2016. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1161/.Accessed 22 August, 2016.

ACMG (American College of Medical Genetics, American Society of Human Genetics Working Group on ApoE and Alzheimer Disease). Statement on the use of Apolipoprotein E testing for Alzheimer disease. JAMA 1995;274:1627–1629.

ADI (Medical and Scientific Advisory Committee and Alzheimer’s Disease International). Consensus statement on genetic testing for Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1995;9:182–87.

NIA (National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association Working Group). Apolipoprotein E genotyping in Alzheimer disease. Lancet 1996;347:1091–1095.

Choosing Wisely. ACMG Provides Recommendations on Genetic Testing Through the Choosing Wisely® Campaign. 10 July 2015 . http://www.choosingwisely.org/acmg-provides-recommendations-on-genetic-testing-through-the-choosing-wisely-campaign/. Accessed 22 August 2016.

Goldman JS, Hahn SE, Catania JW, et al.; American College of Medical Genetics and the National Society of Genetic Counselors. Genetic counseling and testing for Alzheimer disease: joint practice guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and the National Society of Genetic Counselors. Genet Med 2011;13:597–605.

Green RC, Roberts JS, Cupples LA, et al.; REVEAL Study Group. Disclosure of APOE genotype for risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 2009;361:245–254.

Roberts JS, Christensen KD, Green RC. Using Alzheimer’s disease as a model for genetic risk disclosure: implications for personal genomics. Clin Genet 2011;80:407–414.

Tyrone J. The journey from genetic testing to generating hope . Currents (University of California San Diego, Shiley-Marcos Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center) summer 2012;1–2.

Messner JA. Informed choice in direct-to-consumer genetic testing for Alzheimer and other diseases: lessons from two cases. New Genet Soc 2011;30:59–72.

He W, Goodkind D, and Kowal P. An aging world: 2015 (US Census Bureau international population reports, P95/16-1). US Government Publishing Office: Washington, DC, 2016.

Re/code Decode hosted by Kara Swisher. Interview with Anne Wojcicki, 3 April 2016. https://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/re-code-decode-hosted-by-kara/id1011668648?mt=2#episodeGuid=gid%3A%2F%2Fart19-episode-locator%2FV0%2FXjMqFQjIEjXmQTYNq_1kLNl8CPNiyo-to7ChjXCLSdA. Accessed 10 May 2016.

Roberts JS, Barber M, Brown TM, et al. Who seeks genetic susceptibility testing for Alzheimer’s disease?: findings from a multisite, randomized clinical trial. Genet Med 2004;6:197–203.

United Health Care. Personalized medicine: trends and prospects for the new science of genetic testing and molecular diagnostics. Working paper 7 (March 2012) p. 8. http://www.unitedhealthgroup.com/~/media/uhg/pdf/2012/unh-working-paper-7.ashx. Accessed 10 May 2016.

Roberts JS, Chen CA, Uhlmann WR, Green RC. Effectiveness of a condensed protocol for disclosing APOE genotype and providing risk education for Alzheimer disease. Genet Med 2012;14:742–748.

Meilleur KG, Littleton-Kearney MT. Interventions to improve patient education regarding multifactorial genetic conditions: a systematic review. Am J Med Genet A 2009;149A:819–830.

Zallen DT. To Test or Not to Test: a Consumer’s Guide to Genetic Screening and Risk. Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, 2008.

Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, et al.; International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ 2006;333:417–422.

Readability Formulas. Free Text Readability Consensus Calculator. http://www.readabilityformulas.com/free-readability-formula-tests.php. Accessed 26 August 2016.

Zallen DT. Vignettes as an aid to deciding about genetic testing. American Society of Human Genetics annual meeting, Boston, MA, 22–26 October 2013.

JMP® Pro, Version 12.2.0. SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, 2015.

Pearson K. On the criterion that a given system of deviations from the probable in the case of a correlated system of variables is such that it can be reasonably supposed to have arisen from random sampling. Philos Mag Ser 1900;50:157–75.

Kruskal WH, Wallis WA. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. J Am Stat Assoc 1952;47:583–621.

Friedman M. The use of ranks to avoid the assumption of normality implicit in the analysis of variance. J Am Stat Assoc 1937;32: 675–701.

Adair JG. The Hawthorne effect: a reconsideration of the methodological artifact. J. Appl Psychol 1984;69: 334–345.

American Society of Human Genetics. ASHG statement on direct-to-consumer genetic testing in the United States. Am J Hum Genet 2007;81:635–636.

American College of Medical Genetics Board of Directors. Direct-to-consumer genetic testing: a revised position statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet Med 2016;18:207–208.

Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute . Gene Test or Not? https://genetestornot.org. Accessed 25 August 2016.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by award 15-5 from the Commonwealth of Virginia’s Alzheimer’s and Related Diseases Research Award Fund, administered by the Virginia Center on Aging, School of Allied Health Professionals, Virginia Commonwealth University. The development of the prototype decision aid was supported by grants from the College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences and the Institute for Society, Culture & Environment at Virginia Tech.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

(ZIP 37 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ekstract, M., Holtzman, G., Kim, K. et al. Evaluation of a Web-based decision aid for people considering the APOE genetic test for Alzheimer risk. Genet Med 19, 676–682 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2016.170

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2016.170

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Assessing an Interactive Online Tool to Support Parents' Genomic Testing Decisions

Journal of Genetic Counseling (2019)

-

Clinical implications of APOE genotyping for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD) risk estimation: a review of the literature

Journal of Neural Transmission (2019)