Abstract

Study design:

This is a cross-sectional study.

Objectives:

The objective of this study was to ascertain the essential items mediating adequate dietary intake based on the Japanese Food Guide in common among the transtheoretical model (TTM), self-efficacy (SE) and outcome expectancy (OE).

Setting:

Members of the organization Spinal Injuries Japan.

Methods:

We posted a questionnaire survey to 2731 community-dwelling Japanese adults with spinal cord injury (SCI), and responses from 841 individuals were analyzed. Food intake was assessed as the frequency scores of 10 food items eaten in a daily diet in Japan. The correlations between the frequency scores of food intake and TTM, SE and OE were determined by binominal logistic regression analysis.

Results:

The frequency scores of food intake were significantly associated with ‘To eat vegetable dishes (dishes made mainly from vegetables or potatoes) not less than twice a day’, ‘To eat green/yellow vegetables not less than twice a day’, ‘To eat dairy products not less than once a day’ and ‘To eat fruits not less than once a day’ in TTM. ‘To eat vegetable dishes (dishes made mainly from vegetables or potatoes) not less than twice a day’, ‘To eat dairy products not less than once a day’ and ‘To eat fruits not less than once a day’ were significantly associated with the frequency scores of food intake in SE. In OE, no differences were shown.

Conclusion:

This study finds that vegetable dishes, dairy products and fruits are the key items mediating adequate dietary intake. Dietary guidelines promoting the intake of these dishes for SCI individuals are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Approximately 100 000 Japanese currently live with spinal cord injury (SCI), and SCIs occur at a frequency of 5000 every year.1 Many patients with SCI are discharged to private residence,2, 3 and they live a long life. Although they have to take care of their own health for all that time, it is well known that the physiologic and metabolic changes that accompany SCI result in an increased risk of chronic diseases at rates higher than those for the able bodied.4 Adequate diet must be essential for people with SCI to minimize chronic disease risks. However, dietary guidelines for these individuals are absent.

The Japanese diet has attracted considerable attention because of the long life expectancy in Japan. The diet has a unique pattern that consists of grain dishes (mainly rice), main dishes (such as fish, soybeans, egg and meat), side dishes (such as seaweed, vegetables and potatoes), dairy products and fruits. This Japanese dietary pattern is different from the Western dietary pattern based on wheat and meat, and the Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top5 is based on the Japanese dietary pattern. In this food guide, the categories of grain dishes, fish and meat dishes (main dishes), vegetable dishes (side dishes), fruits and dairy products were adopted. In comparison with the Western dietary pattern, the Japanese dietary pattern is found to be lower in total energy, total fat and omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio,6 and it was associated with a decreased risk of chronic diseses.7, 8 Diets based on the Japanese Food Guide have also produced the benefit of reducing future mortality in Japanese women.9

The purpose of this study was to ascertain the key items or categories based on the Japanese Food Guide mediating adequate dietary intake. Adequate dietary intake has been conceptualized as involving a progression through five phases of change, which are precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action and maintenance based on the transtheoretical model (TTM).10 These behavioral changes are predicted by self-efficacy (SE) and outcome expectancy (OE). SE and OE are major elements of the social contextual theory,11 and SE represents the subjects’ level of confidence in maintaining adequate dietary intake across a number of tempting situations. Therefore, we examined the essential items or categories that are common among TTM, SE and OE.

Materials and methods

Subjects and procedures

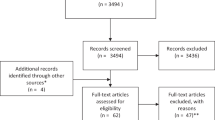

We used a cross-sectional design. The subjects were community-dwelling Japanese adults with chronic SCI, who were registered members of the organization Spinal Injuries Japan (Tokyo, Japan). With permission from the organization director, we posted a study information sheet with a questionnaire to 2731 members in September 2011. The study information sheet explained the aims and purpose of the study, methods, advantages and disadvantages of participating in the study and the management and publication of data, including that the survey was anonymous and to regard a returned questionnaire as a consent form. We received responses from 1000 individuals, but excluded those responses missing crucial data such as sex, age and lesion type. Finally, the responses from 841 individuals were analyzed. The response rate was 30.8%. We did not collect the race of surveyed persons with SCI. However, foreign residents in Japan are only 1.6% of the Japanese population.12 It is considered that the surveyed SCI population is mirroring the Japanese population and that the rate of foreign residents with SCI also is low. In fact, the rate of female individuals with SCI was 15% in this study, almost mirroring the Japanese SCI population (20%).13

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was based on a framework of the modified PRECEDE–PROCEED model.14, 15 The original questionnaire included eight items on quality of life, health status, food intake, dietary and health behavior, TTM, preparation factor (knowledge, attitude, skill, SE and OE), dietary environment and attributes. In this study, we analyzed the association between food intake, TTM and preparation factor: SE and OE. Before using this questionnaire, it was evaluated whether the questions and answers were adequate for the assessment of one’s dietary life by two registered dietitians, the director of the organization Spinal Injuries Japan, a former staff member of the Tokyo metropolitan facility for the handicapped persons and an administration officer of the association for the handicapped persons. Furthermore, it was checked for suitability and clarity by the former staff member of the Tokyo metropolitan facility for the handicapped persons, the administration officer of the association for the handicapped persons and two community-dwelling SCI individuals who were registered members of a sports club.

Food intake

Food intake was assessed as the frequency of intake in 1 day or 1 week of 10 food items. The 10 food items were rice, meat, fish, egg, soybeans/soybean products, dairy products, green/yellow vegetables, other vegetables, potatoes and fruits. These foods are eaten in a daily diet in Japan and are major components of the Japanese diet, which consists of grain dishes, fish and meat dishes, vegetable dishes, dairy products and fruits. The frequency of intake in 1 day was assessed for rice, green/yellow vegetables and other vegetables, and that in 1 week was for other food items. Response choices comprised a four-item Likert scale scored in decreasing order of frequency (score 0−3). The frequency score of food intake was calculated as the sum of each score for the 10 food items (total scores ranged from 0 to 30). These frequency scorings were previously confirmed to relate to the nutritional intakes calculated from the dietary records of middle-aged and elderly persons.16

TTM, SE and OE

In the TTM, SE and OE, participants were asked about seven items: ‘To have a meal consisting of grain dishes, fish and meat dishes, and vegetable dishes not less than twice a day', ‘To eat rice (rice or dishes using a rice) not less than twice a day’, ‘To eat fish dishes at an equal or higher frequency than meat dishes’, ‘To eat vegetable dishes (dishes made mainly from vegetables or potatoes) not less than twice a day’, ‘To eat green/yellow vegetables not less than once a day’, ‘To eat dairy products not less than once a day’ and ‘To eat fruits not less than once a day’. These questions were based on the Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top, which consists of five categories.5 Although vegetables and fruits are often combined into a single category in Western countries, in Japan fruits are often consumed as an after-meal dessert or as a snack rather than as part of the meal. Therefore, fruits were categorized separately from vegetable dishes. Participants were asked to answer the following items in the TTM: ‘I continue to eat for more than 6 months’, ‘I continue to eat for less than 6 months’, ‘I eat sometimes or consider to eat within the next 30 days’, ‘Although I do not eat, I consider to start eating within the next 6 months’ or ‘I do not eat and I do not consider to start eating within the next 6 months’; in OE ‘I think it to be very important’, ‘I think it to be quite important’, ‘I think it to be a little important’, ‘I do not think it to be very important’, ‘I think it to be little important’ or ‘I do not think it to be important at all’; and in SE ‘I have a lot of confidence in eating’, ‘I have quite confidence in eating’, ‘I have a little confidence in eating’, ‘I do not have a lot of confidence in eating’, ‘I have little confidence in eating’ or ‘I do not have any confidence in eating’.

Statistical analysis

Nominal scales were expressed as the number of subjects (rate). Interval scales were expressed as the mean (s.d.) or median. The associations between the attributes and the frequency scores of food intake were analyzed by the χ2-test. The correlations between the frequency score of food intake and TTM, SE and OE were determined by binominal logistic regression analysis. The dependent variables were the frequency scores of food intake, and the independent variables were TTM (model 1), SE (model 2) and OE (model 3). On the basis of the median, the frequency scores of food intake were divided into subgroups, which were the superior group (>16) and the subordinate group (⩽16). The former was scored as 1 and the latter was scored as 0. In addition, the positive answers in TTM, SE and OE were scored as 1 and the negative answers were scored as 0 in consideration with the distribution. Variables were applied by compulsive injection to the calculation of univariate and multivariate analyses. These analyses were adjusted by sex, classification of age, time after injury, lesion type, living alone or with other persons, having a job or not, receiving of public nursing care services or not and social participation. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics v.21 (IBM Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Statistical significance was set at P<0.05 for two-tailed tests.

Statement of ethics

This study was approved by the ethical committee of Tokyo Metropolitan University.

Results

The subjects’ mean age was 61.6 (s.d. 11.5) years in men and 57.8 (s.d. 13.1) years in women. Mean time after injury was 27.6 (s.d. 12.8) years in men and 25.9 (s.d. 14.4) years in women. Other subject characteristics are shown in Table 1. About one half of the subjects (51.6%) had thoracic cord injury, and 29.1% had cervical cord injury.

The mean and median frequency scores of food intake were 16.3 (s.d. 5.1) and 16.0, respectively. The frequency scores of food intake between the superior group and the subordinate group were significantly different in sex, classification of age, living alone or with other persons and receiving public nursing care services or not. The mean frequency scores were 16.0 (s.d. 5.2) among men and 17.6 (s.d. 4.8) among women; 15.2 (s.d. 5.5) in subjects up to 49 years old, 15.2 (s.d. 4.9) in subjects aged 50−59 years, 16.1 (s.d. 5.0) in subjects aged 60−69 years and 18.1 (s.d. 4.9) in subjects aged 70 years or older; 14.2 (s.d. 5.5) among subjects living alone and 16.6 (s.d. 5.0) among subjects living with other persons; and 16.9 (s.d. 5.2) among subjects receiving public nursing care services and 15.8 (s.d. 5.2) among subjects not receiving public nursing care services.

The correlations between the frequency score of food intake and TTM, SE and OE were determined by binominal logistic regression analysis (Table 2). In the univariate analysis, the associations of all the variables were significant and all odds ratios were >1. On the other hand, in the multivariate analysis, the frequency scores of food intake were significantly associated with ‘To eat vegetable dishes (dishes made mainly from vegetables or potatoes) not less than twice a day’, ‘To eat green/yellow vegetables not less than twice a day’, ‘To eat dairy products not less than once a day’ and ‘To eat fruits not less than once a day’ in TTM and ‘To eat vegetable dishes (dishes made mainly from vegetables or potatoes) not less than twice a day’, ‘To eat dairy products not less than once a day’ and ‘To eat fruits not less than once a day’ in SE. There were no differences with regard to OE.

Discussion

Our results suggest that vegetable dishes (containing green/yellow vegetables), dairy products and fruits are the key items or categories based on the Japanese Food Guide mediating favorable dietary intake. There are still few reports defining the items or categories mediated with adequate food intake. Therefore, our results can support an attempt to make a dietary guide for individuals with SCI.

Vegetable dishes and fruits are shown to be important items in this study. The focus area for ‘Nutrition and Diet’ in Health Japan 21 (the second term)17 shows that increasing the consumption of these items is important to prevent chronic diseases and to maintain health, and also to control weight in Japan or other countries.18, 19 However, few longitudinal studies have shown these results for individuals with SCI. Only a few surveys of dietary intake have been performed for individuals with SCI. In a study conducted in 75 men and women with SCI in Canada (mean age: 42.4±11.8 years), one-quarter (26.7%) of participants were adherent to the vegetables and fruit, and grain products recommendations of Eating Well with Canada’s Food Guide. One-third (34.7%) were adherent to the milk and alternative recommendations and two-thirds (65.3%) were adherent to the meat and alternative recommendations.20 In a study of 100 adults aged 38−55 years with SCI and 100 age-matched able-bodied adults in USA, participants with SCI consumed fewer servings of dairy products, fruits and vegetables and whole-grain foods compared with able-bodied persons.21 In addition, the SCI and able-bodied participants who met the 2010 Dietary Guideline recommendations were as follows: 22% versus 54% for dairy, 39% versus 70% for fruits and vegetables and 8% versus 69.6% for whole-grain foods, respectively. In a study of 95 community-dwelling men with paraplegia aged 20−59 years in USA, <35% of the participants met the recommendations of the 1995 Dietary Guidelines for fruit servings and vegetable servings, and only 16% were within the guideline for dairy servings.22 In these studies, vegetables, dairy products and fruits intakes were less adherent to recommendations. Although the dietary guidelines are food based in Canada and USA, the Japanese Food Guide is dish based. Consequently, vegetables are the similar components as vegetable dishes (side dishes) in Japan. The key items in this study are consistent with the foods that had shown dietary inadequacy in the previous studies in Canada and USA. This fact supports the validity of our results.

The frequency score of food intake was significantly related to TTM and SE; however, there was no significant association with OE. In OE, about 50% of the participants in our study answered ‘I think it to be very important’ and 80−90% answered ‘I think it to be very/quite important’. On the other hand, ‘I have a lot of/quite confidence in eating’ was answered by 40−70% of participants in SE. These results may possibly suggest that the individuals in our study do not have enough confidence to recognize the importance of adequately patterned food intake. Therefore, enhancing their SE is thought to be a key approach in dietary education to encourage desirable food intake.

This study has several limitations. First, it should be noted that we did not obtain data for the levels of injury defined by the America Spinal Injury Association classification A or B (motor complete SCI). It is not clear whether the level of injury would influence the correlations between the frequency score of food intake and TTM, SE and OE, and more research is needed. Second, SCI participants were recruited from members of the organization Spinal injuries Japan. Therefore, our findings may not be representative of the overall chronic SCI population in Japan. Third, the frequency scores of food intake used in this study cannot estimate the quantities of food intake. Even though the food pattern is adequate, an excessive quantity of food intake can cause obesity, dyslipidemia and other conditions. The quantity of categories based on the Japanese food pattern to prevent the chronic diseases and to maintain health for individuals with SCI needs to be confirmed in further studies. Fourth, the response rate in our study was low (30.8%). In the surveys carried out in a single center, the high response (more than 60%) was reported.23, 24 However, response rate was 31.8% in Lavelle's study,25 or 35.8% in FluB's study26 using a similar method to our study. Considering these results, the response rate in our study was not necessarily low. Edwards et al.27 found out several ways to increase response: prenotification, follow-up contact, shorter questionnaires and so on. Further study to which these ways will be applied may achieve higher response rate.

In conclusion, this study finds that vegetable dishes, dairy products and fruits are the key items or categories based on the Japanese Food Guide leading to adequate dietary intake for community-dwelling Japanese people with SCI. Dietary guidelines promoting the intake of these dishes for individuals with SCI should be produced immediately to support health maintenance.

Data Archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Katoh S, Enishi T, Sato N, Sairyo K . High incidence of acute traumatic spinal cord injury in a rural population in Japan in 2011 and 2012: an epidemiological study. Spinal Cord 2014; 52: 264–267.

Tsurumi K, Isaji T, Ohnaka K . Multifaceted analysis of factors affecting home discharge of patients with cervical spinal cord injury. Jpn J Rehabil Med 2012; 49: 726–733 (in Japanese) https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jjrmc/49/10/49_726/_pdf (cited 21 October 2014).

Annual Report for the spinal cord injury model systems, 2013−Public resources for National spinal cord injury statistical center. Available from https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/ (cited 15 October 2014).

Garshick E, Kelley A, Cohen SA, Garrison A, Tun CG, Gagnon D et al. A prospective assessment of mortality in chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2005; 43: 408–416.

Yoshiike N, Hayashi F, Takemi Y, Mizoguchi K, Seino F . A new food guide in Japan: the Japanese food guide Spinning Top. Nutr Rev 2007; 65: 149–154.

Tokudome S, Nagaya T, Okuyama H, Tokudome Y, Imaeda N, Kitagawa I et al. Japanese versus Mediterranean Diets and Cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2000; 1: 61–66.

Shimazu T, Kuriyama S, Hozawa A, Ohmori K, Sato Y, Nakaya N et al. Dietary patterns and cardiovascular disease mortality in Japan: a prospective cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 2007; 36: 600–609.

Fulgoni Ш, Fulgoni S, Upton J, Moon M . Diet quality and markers for human health in rice eaters versus non-rice eaters. Nutrition Today 2010; 45: 262–272.

Oba S, Nagata C, Nakamura K, Fujii K, Kawachi T, Takatsuka N et al. Diet based on the Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top and subsequent mortality among men and women in a general Japanese population. J Am Diet Assoc 2009; 109: 1540–1547.

Prochaska JO, Johnson S, Lee P . The transtheoretical model of behavior change. In: Shumaker SA, Schron EB, Ockene JK, McBee WL (eds). The Handbook of Health Behavior Change, 2nd edn. Springer: NY, USA, pp 59–84 1998.

Bandura A . Social Foundations of Thought and Action: a Social Cognitive Theory. Prentice-Hall: Engle-wood Cliffs, NJ, USA. 1986.

The ministry of justice Immigration control of Japanese and foreign nationals. Available from http://www.moj.go.jp/ENGLISH/IB/ib-01.html (cited 16 February 2015).

Shingu H, Ohama M, Itaka T, Katoh S, Akatsu T . A nationwide epidemiological survey of spinal cord injuries in Japan from January 1990 to December 1992. Paraplegia 1995; 33: 183–188.

Green LW, Kreuter MW . Health Program Planning: an Educational and Ecological Approach4th edn. Mc Graw Hill: Boston, MA, USA, pp 7–17 2005.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare A Basic Direction for Comprehensive Implementation of National Health Promotion. 2012 Available from http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-10900000-Kenkoukyoku/0000047330.pdf (cited 16 February 2015).

Mizoguchi K, Takemi Y, Adachi M . Relationship between a positive perception toward work and the dietary habits of young male workers. Jpn J Nutr Diet 2004; 62: 269–283 (in Japanese) https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/eiyogakuzashi1941/62/5/62_5_269/_pdf (cited 21 October 2014).

A basic direction for comprehensive implementation of national health promotion from http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-10900000-Kenkoukyoku/0000047330.pdf (cited 21 October 2014).

Norman GJ, Kolodziejczyk JK, Adams MA, Patrick K, Marshall SJ . Fruit and vegetable intake and eating behaviors mediate the effect of a randomized text-message based weight loss program. Prev Med 2013; 56: 3–7.

Nagura J, Iso H, Watanabe Y, Maruyama K, Date C, Toyoshima H et al. Fruit, vegetable and bean intake and mortality from cardiovascular disease among Japanese men and women: the JACC Study. Br J Nutr 2009; 102: 285–292.

Knight KH, Buchholz AC, Martin Ginis KA, Goy RE, SHAPE-SCI Research Group. Leisure-time physical activity and diet quality are not associated in people with chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2011; 49: 381–385.

Lieberman J, Goff D Jr, Hammond F, Schreiner P, James Norton H, Dulin M et al. Dietary intake and adherence to the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans among individuals with chronic spinal cord inture: a pilot study. J Spinal Cord Med 2014; 37: 751–757.

Tomey KM, Chen DM, Wang X, Braunschweig CL . Dietary intake and nutritional status of urban community-dwelling men with paraplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005; 86: 664–671.

Wong S, Graham A, Green D, Hirani SP, Grimble G, Forbes A . Meal provision in a UK National Spinal Injury Centre: a qualitative audit of service users and stakeholders. Spinal Cord 2012; 50: 772–777.

Wong S, Graham A, Green D, Hirani SP, Forbes A . Nutritional supplement usage in patients admitted to a spinal cord injury center. J Spinal Cord Med 2013; 36: 645–651.

Lavelle K, Todd C, Campbell M . Do postage stamps versus pre-paid envelopes increase responses to patient mail surveys? A randomised controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res 2008; 8: 113.

Flüß E, Bond CM, Jones GT, Macfarlane GJ . The effect of an internet option and single-sided printing format to increase the response rate to a population-based study: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014; 14: 104.

Edwards PJ, Roberts I, Clarke MJ, Diguiseppi C, Wentz R, Kwan I et al. Metho ds to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; 8: MR000008.

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the SCI individuals who participated in this study. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 23500962.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tsunoda, N., Inayama, T., Hata, K. et al. Vegetable dishes, dairy products and fruits are key items mediating adequate dietary intake for Japanese adults with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 53, 786–790 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.78

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.78