Abstract

Study design:

We analyzed longitudinal data on secondary outcomes from participants in a telerehabilitation study.

Objectives:

To examine the factors affecting return to productive activities and employment and the time to these events following a spinal cord injury (SCI).

Setting:

A large southeastern rehabilitation hospital in the United States.

Methods:

We used hazard regression models to analyze data from newly injured people (n=111) participating in an educational intervention post discharge who were followed for up to 2 years. Outcomes were time to return to productive activities and employment.

Results:

Increasing age and being on Medicaid significantly decreased the likelihood of returning to productive activities (P<0.01), while being white (P<0.05) and having a higher median income (P<0.001) significantly increased this probability. The same factors, bar being on Medicaid, affected the return to employment. Whites returned to productive activities 2.5 times sooner than African Americans and employment twice as fast (P<0.001). Being in the 75th income percentile compared with the 25th shortened time to employment by 209 days.

Conclusion:

Findings here suggest that income and race affect the time to return to productivity and employment, while being on Medicaid also has a role in general post injury productivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spinal cord injuries (SCIs) are life-changing events. One area commonly affected is employment. Reported employment rates post SCI vary greatly worldwide.1 One review of the US literature reported a range of 21–67%.2 This range may in part be attributed to differences in (1) study samples, including size, setting, composition, employment status at time of injury and method of sample selection; (2) the interval over which employment is examined; (3) how dates of employment are determined; (4) the type of data analyzed; (5) analytic methods; and (6) different definitions of employment.

Most US studies focus on paid employment, however measured or defined, rather than the broader rehabilitation goal of productive activity, such as vocational training or informal work.3, 4 Also, certain predictive factors for employment have been examined extensively.5 These include demographic factors, such as race, measures of functional status, time since injury and education.1, 6, 7 Two factors receiving scant attention are income and insurance. Mackenzie et al.8 examined socio-economic correlates of employment, including age, race, education, social support and income at 6 and 12 months post traumatic injury among those employed at the time of injury. Income and social support were the only two significant factors affecting return to employment, with income having the largest role.

In a retrospective study of 154 individuals with SCI, DeVivo et al.9 found that income did not predict employment status, but that unemployed people with SCI had fewer outside sources of support, including private health insurance, workmen's compensation or other types of benefits.

The effect of health insurance coverage on employment is another area in which data are lacking. The role of health insurance is potentially important as it can affect the course of treatment following a SCI. In the United States, the most common treatment pathway is admission to an acute hospital for immediate treatment post injury, then transfer to an inpatient rehabilitation facility after the patient stabilization. For less severe injuries, transfers to home coupled with outpatient programs or home health care may also be options.

In the United States, no single, nationwide system of health insurance or benefit package exists. People purchase health insurance through private insurance plans, either individually or through their employer, or qualify for insurance through one of two government-sponsored plans, Medicare and Medicaid. Administered by the federal government, Medicare is a uniform, national public health insurance program primarily for elderly people. Medicaid is jointly financed by the states and the federal government, but administered by states alone. It covers certain low-income groups. Approximately 14% of the population receives coverage through Medicare, 13% through Medicaid, 68% through the private health insurance market, with the remainder of the population constituting the uninsured.10 Insurance benefits (hereafter insurance benefits refer to health insurance benefits or arrangements), meaning what health care is paid for by the insurer, for how long and under what circumstances, differ by payers. Insurance arrangements may thus affect the length of stay at a facility or the amount of outpatient or in-home care covered post acute discharge. Insurance through contractual arrangements may also affect the pool of providers available to the person seeking care.

Aside from the impact on care pathways, insurance can also affect incentives to return to work or to seek employment. The majority of people in the private health insurance market obtain insurance through their employers. Maintaining current insurance can generate a strong incentive to return to work. Alternatively, Medicaid is income dependent and those eligible must ensure they do not exceed certain income levels to remain eligible; thus Medicaid coverage can act as a disincentive to work.

A retrospective, cross-sectional study11 examined the relationship between the current type of insurance: catastrophic (that is, no-fault automobile insurance or worker's disability compensation), Medicaid, and/or private, and functional and psychosocial outcomes for those injured for at least 2 years. People with private health insurance were more likely to be engaged in work and school activities than those with Medicaid or catastrophic coverage. Medicaid sponsored subjects were younger, more often single, non-white, rehabilitated in an urban setting, and unemployed prior to injury.

Purpose

We examined the factors affecting return to productive activities and employment post injury and the time to these events. We focused on two economic factors that to date have received little attention: income level and health insurance status at the time of injury. Additional contributions of this paper are as follows. The sample was gathered from a single facility, which minimizes variation in initial treatment pathways. We followed the sample at monthly intervals from the onset of injury, so the time of events since onset was recorded with relative precision. Problems of attrition, recall bias and observation bias that have been noted in the literature are avoided.7, 12 We examined return to productive activities as a wider rehabilitation goal and focused on return to employment among those employed at injury only, as becoming employed is likely to be a different process than returning to work. We used hazard regression models,13 to account for the varying durations of observation of participants that overcome the limited predictive value of cross-sectional studies.

Materials and methods

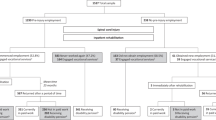

We analyzed data on secondary outcomes from a cohort of newly injured people (n=111) who participated in a telerehabilitation intervention. Details of the study intervention have been described in detail elsewhere.14 Briefly, post discharge, participants were interviewed monthly by trained research staff regarding the development of secondary conditions and certain events, such as returning to work. Enrollment was ‘rolling’, so participants were recruited from the rehabilitation hospital as they were discharged.

We collected demographic data, Functional Independence Measure scores, level of injury and insurance status at the time of discharge. We collected time to participation in productive activities and employment as secondary outcomes during follow-up interviews using the Quality of Well-being Scale.15 Productive activities were defined as attending school, vocational training, working as a homemaker or volunteering.

Actual income data were not obtainable as part of the medical record at the time of discharge and are sensitive data to collect. Special surveys are often used to collect income data.16 We imputed income by using the median income value for the city closest to each participant's zip code, based on census data.17

Analyses

We used hazard regression models to identify the factors affecting return to productive activities and employment. Hazard models are specifically designed for longitudinal data where participants are observed for different lengths of time.13 A Weibull function was chosen for flexibility in the hazard function and was used to model median times to events for the full sample and by race and income.

Participation time ranged from 9 weeks to 2 years. Eighty-two participants were followed for 2 years, while 90 were followed for 1 year. Overall, participants who left the study (n=26) did not differ significantly from those who remained in the study. Reasons for dropping participants included loss of contact with the participant (14%), requests to leave the study (6%) and death (4%).

We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Results

Table 1 provides demographic information on the study population. The mean age of the sample was 35 (s.d.=11.8) years and over three quarters were white and male. The mean discharge Functional Independence Measure was 86, indicating a moderate functional level for the group. Sixteen percent of the sample had cervical complete (American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale A) injuries. Nearly 70% of participants were privately insured, while 80% were employed at the time of injury.

Table 2 provides the regression results for factors affecting return to productive activities. Being older and being on Medicaid significantly decreased the likelihood of reporting a return, while higher income and being white significantly increased the likelihood. Being in the intervention groups, either video or telephone trended negatively (P=0.083) in terms of returning to pre-injury activities, possibly because being in the intervention influenced participants’ self-assessment of their abilities.

Results for returning to work for those employed prior to injury are provided in Table 3. Older age, being white and having a higher income again were the significant factors affecting return to work; all directional effects were consistent with findings in Table 2. In this instance, being on Medicaid (P=0.10) and having a quadriplegic injury (P=0.08) were nonsignificant trends (P>0.05). Being female was not a significant factor in any of the equations.

The median number of days for returning to productive activities and employment are shown in Table 4 by income and race. Participants reported returning more quickly to productive activities at 1.5 years, compared with employment at 1.8 years. Fifty percent of African Americans reported returning to productive activities at 3.5 years, compared with whites at 1.3 years. Those in the 75th income percentile returned to work about 1.4 times faster (209 days) than those in the 25th percentile.

Discussion

Many of the findings here, under stronger methods, mirror those of previous studies. The data indicate that being older at the time of injury significantly decreases the likelihood of return to employment and productive activities, while being white significantly increases this probability. Unlike most other studies, gender played no role in either affecting the time to return to work or to productive activities. One explanation for the effect of gender is that it acts as a proxy for financial resources and the type of work.1 Analytic methods and taking income into account may explain its lack of effect here.

The effect of health insurance at the time of injury is noteworthy. Being uninsured did not affect either the likelihood of returning to employment or productive activities. However, being insured by Medicaid at the time of injury significantly reduced the likelihood related to general productive activities, such as training or seeking employment. This result was similar to that of Tate et al.11 who found that SCI survivors with private pay insurance were more likely to engage in work and school activities than those with Medicaid coverage. Other work reports that fears of losing insurance benefits generally act as a disincentive to return to work, although they do not distinguish between insurance types.1 In this study, among those employed at the time of injury, the effect of Medicaid was a negative, but nonsignificant trend (P<0.10).

Understanding the role of health insurance in employment paths post injury is important in aiding in the design of effective assistance programs. For example, for those covered by Medicaid, programs must address the issue of maintaining this insurance as their incomes rise, particularly as their health needs have likely increased post injury, or assisting them in transferring to a new insurance policy. In the United States, very few programs, such as the ‘Ticket to Work Initiative’, have been designed to help people with disabilities secure employment, while maintaining all or some of their Medicaid benefits.18

Future research must address clear questions to move the discussion forward and longitudinal studies are critical. For example, benefits at the time of injury may differ from those for which an SCI survivor becomes eligible post injury. The effect of benefits on work may be different for those returning to employment versus not employed at the time of injury. Benefits may also be important if they act as a disincentive to seeking education and training, as the results here suggest. Decisions about education and training in the short run affect the likelihood of future employment.

Being white and having a higher income played a significant role in both models with the same effect: both were related to a higher likelihood of return to work or productive activities. The effect of race has been well documented,5 but this is the first study to show that race acts as a barrier even when income and insurance status at the time of injury are taken into account. The effect remains among the subset of those employed at the time of injury. These findings point to the importance of examining what structural barriers may exist for African Americans who are seeking work post injury, such as transportation, employment discrimination or access to care. Understanding how race relates to these structural barriers, within a larger sample, could help to extend the current findings.

Income, at the time of injury, can impact the ability to return to work and productive activities in multiple ways. Those who are wealthier may be able to purchase equipment, secure transportation or hire assistants that would enable them to go to school or return to work. They also are more likely to have funds to pursue school or vocational training. Income may also be acting as a signal for other factors.

Low income may proxy job type and at the time of injury indicates a lower paying job and one that is more likely to require skilled labor. A person with an SCI may no longer be able to perform the work required to return to such employment.7 Low income is also likely to reflect the effect of educational attainment up to the onset of injury. Education is known to be a primary predictor of employment and relatedly income.19 Education and income are highly correlated, including for people with SCI.20 Education has been found to be an important predictive factor in relation to SCI employment, but these analyses do not include income. When income and education are included simultaneously, education can become insignificant.8

This study has a number of limitations. It was based on a small sample from a single rehabilitation hospital. Age and gender mix were similar to that of the national population, while nationally a larger proportion of racial and ethnic minority groups comprise those with SCI.21 Also, the state of the labor market at the time may have affected the overall availability of jobs. Income was imputed by zip code and city of residence and was not collected for each study participant, although this method has been validated in previous work.17 The sample size was relatively small, so we may have been limited in terms of power to identify significant relationships.

Conclusions

Disentangling the effects of income, insurance, education, all of which can change over time, is critical to address and understand in relation to their interaction with race. The analysis here focuses on key issues: longitudinal data, and insurance and income at the time of injury. The literature is ripe for investment in more refined data to facilitate further analyses of these factors in a larger population.

Data Archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Anderson D, Dumont S, Azzaria L, Le Bourdais M, Noreau L . Determinants of return to work among spinal cord injury patients: a literature review. J Vocat Rehabil 2007; 27: 57–68.

Lidal IB, Huynh TK, Biering-Sorensen F . Return to work following spinal cord injury: a review. Disabil Rehabil 2007; 29: 1341–1375.

Krause JS, Kewman D, DeVivo MJ, Maynard F, Coker J, Roach MJ et al. Employment after spinal cord injury: an analysis of cases from the model spinal cord injury systems. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 1492–1500.

Rintala DH, Hart KA, Preibe MM, Ballinger DA . Racial and ethnic differences in community reintegration in a community-based sample of adults with spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 1998; 4: 1–17.

Ottomanelli L, Lind L . Review of critical factors related to employment after spinal cord injury: implications for research and vocational services. J Spinal Cord Med 2009; 32: 503–531.

Meade MA, Lewis A, Jackson MN, Hess DW . Race, employment, and spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 1782–1792.

Krause JS, Terza JV, Saunders LL, Dismuke CE . Delayed entry into employment after spinal cord injury: factors related to time to first job. Spinal Cord 2010; 48: 487–491.

MacKenzie EJ, Morris Jr JA, Jurkovich GJ, Yasui Y, Cushing BM, Burgess AR et al. Return to work following injury: the role of economic, social, and job-related factors. Am J Public Health 1998; 88: 1630–1637.

DeVivo MJ, Rutt RD, Stover SL, Fine PR . Employment after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1987; 68: 494–498.

Santerre RE, Neun SP . Health Economics: Theories, Insights and Industry Studies, 5th edn South-Western Cengage Learning: Mason, OH, 2008.

Tate DG, Stiers W, Daugherty J, Forchheimer M, Cohen E, Hansen N . The effects of insurance benefits coverage on functional and psychosocial outcomes after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1994; 75: 407–414.

Cifu DX, Keyser-Marcus L, Lopez E, Wehman P, Kreutzer JS, Englander J et al. Acute predictors of successful return to work 1 year after traumatic brain injury: a multicenter analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997; 78: 125–131.

Martinussen T, Scheike TH . Dynamic Regression Models for Survival Data. Springer: New York, NY, 2006.

Phillips VL, Vesmarovich S, Hauber R, Wiggers E, Egner A . Telehealth: Reaching out to newly injured spinal cord patients. Public Health Rep 2001; 116 (Suppl 1): 94–102.

Kaplan RM, Anderson JP, Ganiats TG . The quality of well-being scale: rationale for a single quality of life index. In: Walker SR, Rosser RM (eds). Quality of Life Assessment. Kluwer Academic Publishers: Hingham, MA, 1993 pp 65–94.

Krause JS, Terza JV, Dismuke C . Earnings among people with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008; 89: 1474–1481.

Krieger N . Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: validation and application of a census-based methodology. Am J Public Health 1992; 82: 703–710.

Atwell S, Hudson LM . Social security legislation creates ticket to work and work incentives improvement act. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2004; 9: 26–32.

Cable G . Income, race, and preventable hospitalizations: a small area analysis in New Jersey. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2002; 13: 66–80.

Ramakrishnan K, Loh SY, Omar Z . Earnings among people with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2011; 49: 986–989.

The National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. Annual Report for the Model Spinal Cord Injury Care Systems. 2010; https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/public_content/pdf/2010%20NSCISC%20Annual%20Statistical%20Report%20-%20Complete%20Public%20Version.pdf. Accessed on 5 October 2011.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. We thank the research staff at the Crawford Research Center at Shepherd Center for their assistance with this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Phillips, V., Hunsaker, A. & Florence, C. Return to work and productive activities following a spinal cord injury: the role of income and insurance. Spinal Cord 50, 623–626 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2012.22

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2012.22

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Return to work after traumatic spinal fractures and spinal cord injuries: a retrospective cohort study

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Socioeconomic consequences of traumatic and non-traumatic spinal cord injuries: a Danish nationwide register-based study

Spinal Cord (2022)

-

Predicting prolonged sick leave among trauma survivors

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Hospital- and community-based interventions enhancing (re)employment for people with spinal cord injury: a systematic review

Spinal Cord (2016)

-

Race–ethnicity and poverty after spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2014)