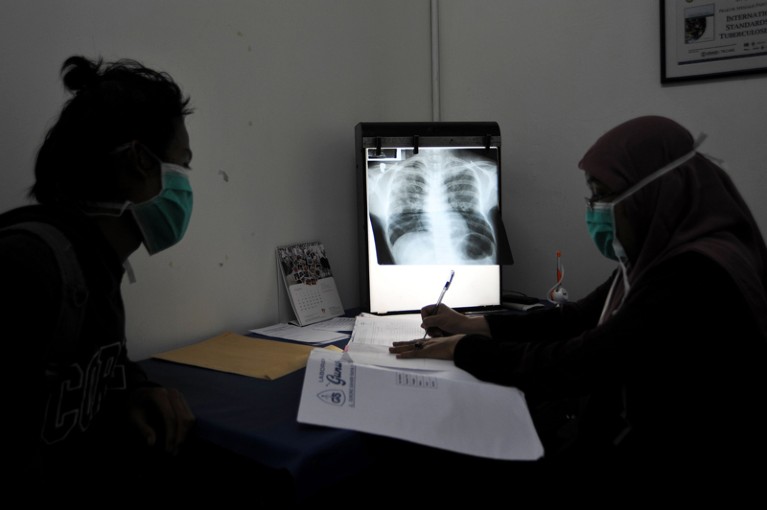

A tuberculosis patient consults with their doctor in Indonesia. Diagnosis and treatment of the disease has been severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.Credit: Jefri Tarigan/Anadolu Agency/Getty

Researchers and clinicians are upset and frustrated that decades of work in diagnosing, treating and researching tuberculosis (TB)have massively stalled. The slowdown means the world is losing ground against a disease that kills 1.5 million people every year.

As the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease held its annual conference online last week, Guy Marks, the union’s president, spoke for many when, comparing efforts against COVID-19, he said: “Many of us who work in the [TB] field feel robbed that equivalent efforts to develop a TB vaccine have never been as well committed or funded.”

Marks added: “The failure to deliver COVID-19 vaccines to low- and middle-income countries and end tuberculosis are two sides of the same coin — a devaluation of human life in poor countries.” He has a point. But it doesn’t need to be this way.

How COVID hurt the fight against other dangerous diseases

Researchers are again urging decision-makers to revive diagnosis, treatment and research programmes for TB and other infectious diseases, such as malaria. And they are saying that much can be learnt from how the creation of COVID-19 vaccines was fast-tracked.

Researchers have been warning that even more people will die from TB and other infectious diseases, such as malaria and HIV, if health systems continue to neglect these infections because of the continuing focus on coronavirus (see Nature 597, 314; 2021). And they are pleading with funders and governments not to drop the ball on TB work.

But their warnings are not being heeded. Not only are more people dying of the disease, but a target to reduce deaths by 90% from 2015 levels by 2030 — part of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals — is now in peril. According to research published this month, this failure will also lead to profound economic and health losses in the trillions of dollars — with the greatest impact in sub-Saharan Africa (S. Silva et al. Lancet Glob. Health 9, E1372–E1379; 2021).

A crucial problem is that fewer medical professionals have been available to diagnose and treat TB. As a result, the number of people diagnosed with the disease fell from 7.1 million in 2019 to 5.8 million in 2020. India, Indonesia and the Philippines are the most affected countries, according to the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) latest TB report, published this month (see go.nature.com/3re4n6j).

Nature Index 2021 Infectious disease

At the same time, funding has also shrunk. Global spending on TB diagnostic, treatment and prevention services dropped from US$5.8 billion to $5.3 billion in 2020. Moreover, this overall spending is less than half of the WHO’s global target of $13 billion annually by 2022. TB research funding is also half of what it needs to be. The WHO set a separate target for this of $2 billion annually for 2018–22. In 2019, funding for TB research totalled only $901 million. By contrast, the US National Institutes of Health alone has set aside $4.9 billion for research on COVID-19. Published research in TB seems to be holding up for now, according to an analysis published this week in Nature Index (see Nature 598, S10–S13; 2021).

Some conference delegates spoke of lowering the targets for diagnosing and treating TB (and for other infectious diseases) to account for these and other ground realities. But that would be inadvisable. Although the COVID-19 pandemic is the highest priority for political leaders, wealthier nations and philanthropic donors, the pandemic has also shown how it is possible to boost both research into an infectious disease and treatment — and to do so at speed, which has led to COVID-19 vaccines in record time.

Lessons from COVID-19 must be applied to the fight against TB and other infectious diseases — from extraordinary resource mobilization to the use of emerging technologies, such as messenger RNA and other platforms to create vaccines. Advances in rapid and reliable diagnostics, advanced computation, sequencing and clinical-trial capacity for new vaccines and treatments can all be harnessed for TB and other infectious diseases.

The TB vaccine in use today is essentially the same as the Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine introduced in July 1921. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown that it’s possible to produce new vaccines in one year, not 100 — provided that there is funding and political will.

Nature Index 2021 Infectious disease

Nature Index 2021 Infectious disease

How COVID hurt the fight against other dangerous diseases

How COVID hurt the fight against other dangerous diseases

How COVID is derailing the fight against HIV, TB and malaria

How COVID is derailing the fight against HIV, TB and malaria

How COVID spurred Africa to plot a vaccines revolution

How COVID spurred Africa to plot a vaccines revolution

How to stop COVID-19 fuelling a resurgence of AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis

How to stop COVID-19 fuelling a resurgence of AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis