Key Points

-

Highlights the importance of the combination of alcohol and tobacco usage as risk factors for oral cancer.

-

Dental access centres attract significant numbers of patients who would benefit from health advice about oral cancer, but a more sophisticated approach to informing patients is required.

-

Encourages commissioning bodies to become involved in providing oral cancer information in dental access centres.

Abstract

Objective In the United Kingdom in 2006, 5,325 persons were diagnosed with oral cancer; and in 2007 it caused around 1,850 deaths. The purpose of this study was to assess the patient awareness, in a dental access centre, of a poster and leaflet campaign providing information about smoking and excess alcohol consumption as risk factors in the development of oral cancer, and to explore dental patients' beliefs and perceptions about these risk factors.

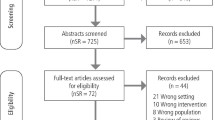

Methods Posters and leaflets providing information about risk factors for oral cancer were displayed in the patient waiting areas of a dental access centre. Data were collected prospectively in relation to the smoking and drinking habits of patients attending the centre. This information was used to categorise patients into one of four groups ranging from low to high consumption. During triage, patients were asked if they had read any of the information about oral cancer that was on display, and patients in the high risk groups were asked to participate in a semi-structured interview that would explore their knowledge about risk factors and their views on the delivery of healthcare messages in relation to oral cancer.

Results Data on risk status and exposure to the poster and leaflet campaign were collected for 1,161 patients attending during the study period. More than 50% of these patients were smokers, with 36% in the high or very high tobacco and alcohol use groups. Approximately 40% of patients within each consumption group had read any of the information available. Nine patients agreed to be interviewed and overall knowledge about risk factors for oral cancer, even after reading the information was poor.

Conclusion Dental access centres attract a significant number of patients with lifestyle habits that make them vulnerable to oral cancer, and as such are well placed to deliver oral health messages to this high risk group. However, the delivery of information through a simple poster and leaflet campaign is likely to have limited impact.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The incidence of oral cancer is increasing.1 Surgical techniques and non-surgical management of oral cancer have become more advanced in recent years,2 but it continues to be associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality.2,3 Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) accounts for 95% of oral cancers.2 The disease is largely preventable by avoiding known risk factors.2,4,5 The main risk factors are smoking and high levels of alcohol consumption, particularly with the two acting synergistically,6 although it is recognised that other risk factors are emerging,7 implicated, for example, in the development of oral cancer in some younger patients.8,9 The incidence of oral cancer increases with age.1,10 In the UK the majority of cases (86%) occur in people aged 50 or over,11 though the incidence in younger adults is increasing.1 OSCC is seen predominantly in males, although the male:female differential is decreasing.1

Both population screening and primary prevention using health education have been advocated as methods of disease control.12 While the evidence for the effectiveness of oral cancer screening programmes is equivocal,13,14 it has been suggested that opportunistic screening in dental practice is a realistic alternative to population screening.15 Numerous authors also support a primary preventive approach of promoting smoking cessation and reduction of alcohol consumption.10,16,17

There is a general lack of knowledge about oral cancer among the UK population18,19 and even among some medical and dental professionals.2 While it would appear that tobacco usage is widely recognised by patients as a risk factor for OSCC, the effect of alcohol is not.4,19 A previous study identified that significant numbers of patients attending the dental access centre in Nottingham (Integrated Dental Unit, IDU, Nottingham) have lifestyle habits that make them vulnerable to oral cancer, and that dental access centres might be well-placed to play a role in the prevention of the disease.20 The purpose of this paper is to determine the extent of patient awareness of a combined poster and leaflet campaign providing opportunistic information about the risks of smoking and excess alcohol consumption to patients whose lifestyle habits place them at risk of developing oral cancer.

Methods

Before data collection, the study went through usual NHS ethical and organisational approvals processes. Data were collected during two time periods in line with the poster campaign being run at the Integrated Dental Unit (5 November 2007-21 December 2007, and 19 May 2008-11 July 2008). Mouth cancer information leaflets provided by Cancer Research UK were displayed in the patient waiting areas of the IDU together with a number of A4 posters with bullet-point facts about oral cancer. The posters were produced by the Oral Health Promotion team at Nottinghamshire County Teaching PCT. Before their consultation with the dentist, all patients aged 18 years and over attending within these time periods were asked by the triage nurse if they had read the information provided as part of the information campaign. As in the earlier study,20 information routinely provided by all patients regarding their alcohol and tobacco consumption was used to place them into one of four groups. This was not an attempt to classify the true relative risks, but was used to identify target groups that might benefit from brief public health interventions.

These groups were as follows:

-

1

Low tobacco and alcohol use group: non-smokers who either do not drink alcohol or drink less than 20 units per week

-

2

Moderate tobacco and alcohol use group: smokers who do not drink alcohol and who smoke up to 20 cigarettes per day

-

3

High tobacco and alcohol use group: smokers who consume up to 20 cigarettes per day and drink up to 20 units of alcohol per week

-

4

Very high consumption group: smokers using in excess of 20 cigarettes per day, and/or drinking in excess of 20 units of alcohol per week

Patients in the high and very high consumption groups were asked if they would participate in an interview with a researcher to explore their knowledge and beliefs about risk factors shown to be linked with oral cancer. Patients interested in participating in the interview were provided with an information pack that included a description of the study, a consent form and contact details for the research team. Participants were also offered a £15.00 gift voucher in recognition of taking part in the study. All patients who agreed to take a study information pack were also given a mouth cancer leaflet to read.

As it was anticipated that uptake to the interview phase of the study would be low, a true purposive approach to sampling could not be taken and instead all patients who returned their contact details to the researcher were interviewed. Initially face-to-face interviews were conducted but as initial uptake was very poor, the study team amended the protocol and offered participants the option to be interviewed over the telephone. Of the nine interviews that were completed, two were done face-to-face and seven were conducted over the telephone. All interviews were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim. Thematic analysis was undertaken by the researcher and the analysis and interpretations were verified by a second researcher with experience of qualitative research methods.

Results

Awareness of the poster and leaflet campaign

During the study period, 1294 patients attending the IDU meeting the eligibility criteria were asked about their alcohol and tobacco consumption and their awareness of the poster and leaflet campaign. Of these, complete data relating to consumption and whether or not they had read the information were collected for 1161 (89.7%). The median age of participants was 32 years and just over half (57.2%) were men. Table 1 gives consumption by age and gender. Overall 624 (53.7%) were smokers categorised as being in the moderate, high or very high consumption groups. Of these 424 (36.5%) were in the high or very high consumption groups. Men were significantly more likely than women to be categorised as being in high or very high consumption groups (Chi-square = 12.95, df = 1, p <0.001, OR 1.59, 95% CI 1.22-2.06), with 41.1% (n = 273) of men being in these higher risk groups compared to 30.5% (n = 138) of women.

Overall 46.1% (n = 535) of participants reported that they had read at least some of the information on display (see Table 2). The number reporting having read any of the information in each consumption group did not differ significantly, with 48.6% (261 of 537) of those in the low consumption group reporting having read at least some information, compared with 44.1% (160 of 363) of those in the high consumption group (Chi-square = 2.73, df = 3, p = 0.44). Most of those who had read any information had read the poster only, with approximately 40% of participants across the consumption groups having read the poster but not the leaflets available. Few had read the leaflets provided (47 of 1033, 4.5%) and very few had read both the poster and the leaflet (25 of 1038, 2.4%).The participants were asked if there was a reason they had not read the information. Of the 338 that did give a reason, as shown in Table 3, most stated that they had not seen any of the information provided (199 of 338, 58.9%) and a further 10.7% (36 of 338) said they were in too much pain to read it.

Findings from the semi-structured interviews

To explore patients' knowledge and perceptions of oral cancer and to determine how much of the information provided about the disease was retained, nine semi-structured interviews were completed with patients identified as being in the high or very high consumption groups. Five of the participants were male and four were female. Two of the female participants were considerably younger (22 years) than the other participants whose ages ranged from 36 to 58 years of age. All of the participants described themselves as white British.

Knowledge and perceptions of the disease

All of the participants asked to consider taking part in the interview phase of the study had received an information leaflet outlining the causes, signs and symptoms of oral cancer. Although all but one of the participants stated that they had read it, overall knowledge about the disease was limited. When asked a general question relating to what they knew about the disease, most reported that they knew nothing at all:

'No. I mean how does it get there in the first place as well? You know, is it because you're not cleaning your teeth or is it stuff you're eating? I mean you know if you eat crisps or summat, sometimes you get a slit, you know, does it work that way? I don't know. And there again what's the treatment for it if you have got it?' Participant 2. Male aged 52 years.

When prompted, most thought that smoking would put them at increased risk, largely because smoking was generally related to cancer risk:

'Generally I'm going to be a lot more prone to it because I've been a lifelong smoker. I'm aware of the fact that that is why I get a lot of gum inflammation problems, which is why I use mouth wash and stuff like that. Apart from that I don't know whether it's sort of fatal or in modern times curable.' Participant 4. Male aged 48 years.

The respondents had retained very little information about other key issues. They knew little about prevalence for example and when age of onset was reported it was described as being 'older'. Information on the signs and symptoms to look out for was also not generally well retained. Although overall knowledge of the disease was low, most of the participants did state that they examined their mouths for anything unusual. Few however felt that they knew the signs and symptoms they should be looking for that might indicate oral cancer. Ulcers or 'white specks' were mentioned as something that might be a cause for concern:

'I've just been looking for white specks.' Participant 8. Male aged 44 years.

'...signs of it are that you keep getting ulcers or them other things, I forget what you call them now, they're like big boils?' Participant 3. Male aged 58 years.

Risk factors and risk-taking behaviour

All of the respondents were smokers and two were also heavy drinkers. Although most thought that their smoking put them at risk of oral cancer and cancer generally, less than half of the respondents knew that alcohol consumption had any association with risk of oral cancer. Of the respondents that were heavy drinkers, one did not know that alcohol was an associated risk factor and the other assumed it was but hadn't picked this information up from the leaflet provided. Three respondents did state that they had picked up this information from the leaflet provided at the IDU and overall the respondents were surprised that alcohol consumption was associated with risk of the disease:

'Well the thing, the main thing I associate with drinking, the thing most guys associate with drinking is kidney failure....with regards to smoking people know that it causes lung cancer but with regards to mouth and throat cancer, no, people are very under-informed about that.' Participant 4. Male aged 48 years.

'I know I'm at higher risk from it (oral cancer) because I smoke. I wasn't aware of being at higher risk from drinking until I read it on one of the leaflets when I was at the place (the IDU). I don't really know much about what, you know how it's different to other types of cancer.' Participant 5. Female aged 22 years.

Although all of the respondents knew or at least suspected that their smoking status put them at increased risk, only one participant reported that this knowledge would actually impact on their behaviour, with one other stating it would add to her determination to quit smoking. Several talked about seeing friends and family members suffering from or dying from cancer but this hadn't impacted upon their smoking status. This may reflect a fatalistic approach to risk:

'I personally think it's all a case of luck of the draw, I've known people who have had cancer that have been really healthy. You know, I've known people who have had heart attacks that have been healthy since they were children.' Participant 6. Female aged 48 years.

Profile of the disease

The participants were asked if they had discussed oral cancer with a health professional. None of the respondents had discussed the disease with a dentist and only one had ever discussed it with their GP. The respondent who had discussed it with her GP had done so after her friend had been diagnosed with an oral tumour. The GP had given this participant some information about the signs and symptoms of the disease but she was not able to recall them at the time of the interview.

The respondents thought that the dentist would look for symptoms of the disease as part of a routine examination, though most of the respondents did not have a regular dentist either due to limited availability or because of the cost associated with treatment:

'I'm not prejudiced or anything but it seems like I'm a white British male, I've paid all my taxes, I've never been on the dole... you know paid all my national insurance... and everything and you know and yet when I'm really in pain with me dental stuff, if I can't afford it, I can't get it done...' Participant 8. Male aged 44 years.

The respondents felt that oral cancer didn't have the same profile as other cancers, that most people know very little about oral cancer and that the key messages about risk factors were not adequately relayed to the general public:

'Well I think it should be broadcast on television and newspapers because a lot of people don't know anything about it. I never knew you could get cancer in the mouth until I went into the walk-in centre. I knew you could get in the throat but not the actual mouth.' Participant 3. Male aged 58 years.

'...friends that I have that are particularly smokers, like we all know about some of the dangers but I don't think there's a particularly in-depth knowledge about mouth cancer specifically. I think the TV advertising things they [do] always put the emphasis on like smoking and lung cancer.' Participant 5. Female aged 22 years.

Health messages

The respondents gave a range of suggestions related to how key messages should best be relayed. Providing information in non-health settings as well as health settings such as the GP and dental surgery was thought to be important. These included pubs, clubs, job centres and day centres. In health settings such as GP and dental surgeries, the sheer volume of health messages provided was thought to reduce their impact. One participant also felt that the books and magazines provided in these settings were a distraction and that this also reduced the impact of health messages:

'Get rid of the magazines and have things there people can read about what's more important.' Participant 2. Male aged 52 years.

Another participant talked about being 'bombarded' with health messages and felt that too much information left people feeling immune to the message being relayed:

'I don't want to be bombarded because it's not, ...just mouth cancer, you tend to get numb to things like you got, at the moment they got the big thing about obesity and smoking and then...you just get immune to it.' Participant 6. Female aged 48 years.

Television and media campaigns generally were considered to be an effective way of relaying key information, and campaigns for other cancers such as prostate, breast and lung were mentioned as examples of high-profile campaigns:

'Everyone takes notice of telly, that's where I noticed the prostate thing, you know, people are lazy, and they won't go and look for information, so they wait till it's sort of rammed down their throat and then they'll take more notice of it... you know, to be honest, what you could do with is someone famous getting it [oral cancer], couldn't you?' Participant 8. Male aged 44 years.

'...maybe like some adverts on TV or something like that, because when it's like breast cancer or anything like that they do like a week, don't they, where it's breast cancer awareness week...or they do things in shops like T-shirts for breast cancer. So maybe if people was more aware about mouth cancer, because I don't think many people are really that aware on how you get it or what it is.' Participant 9. Female aged 22 years.

Some of the participants talked about having the key information relayed to them by a health professional as part of a consultation, either because written information was not accessible to those with low levels of literacy or because it would have more impact than having the information provided alone. Issues such as cost and accessibility to those who work during office hours were also raised:

'...if you come in and discuss it [oral cancer] and also get a free dental check at the same time, which would make people, you know, [make] a bit more of an effort to get in. Especially people who pay, that's a good thing.' Participant 6. Female aged 48 years.

Discussion

Analysis of the data provided by patients attending the Integrated Dental Unit (IDU) showed that over 50% were smokers. This compares with a national average of 21%21 although smoking rates across the county of Nottinghamshire are generally higher.22 Approximately 36% of patients reported smoking up to or more than 20 cigarettes a day, and drinking up to or more than 20 units of alcohol a week. It is also likely that these self-reported figures represent an underestimate of actual alcohol and tobacco consumption.23,24

Although a significant proportion of patients attending the access centre have risk factors for oral cancer, few oral cancers will present clinically, as patients are predominantly under the age of 45 years.20 The value of oral screening and provision of information about self-examination for these individuals may therefore be limited, unless the trend of increasing prevalence of oral cancer in younger patients continues. Of more importance is advice about risk factors, as it is likely that some of these young patients with adverse lifestyle habits will develop oral cancer in later life.20

In this study, approximately 40% of patients in the target groups read the information available. Disappointingly, it would seem that even after reading the information available, patients' knowledge of risk factors remains poor, and this suggests that the impact of presenting information in this format in the dental access centre will be limited. Other studies have demonstrated that patient information leaflets are effective in increasing patient knowledge and awareness of risks related to oral cancer.12,25,26,27 These studies have involved patients attending medical and dental practices for routine care, have tested patient knowledge immediately after reading the information leaflet, and were not specifically targeted at high-risk individuals. In addition, patients were handed the information leaflet by the researcher. In this study the poster directed patients to the leaflets for additional information, but were taken up by only a few patients.

The role of the dental profession in the early recognition of oral cancer via opportunistic oral mucosal screening is well established28 and may be cost-effective in general practice.29 Patients are positive about dentists providing smoking cessation advice,30 however, there are professional hurdles. Members of the dental team may be willing to implement smoking cessation strategies in dental practice, but lack of patient education material is perceived as a barrier,31 and it has been suggested that some dental teams fail to engage patients in smoking cessation advice.32,33 Similarly, although patients are supportive of dentists' providing advice regarding alcohol use,34 giving such advice is perceived by dentists to be difficult.35 More significantly, oral cancer is associated with low socio-economic status.36,37

Those most at risk of developing oral cancer are least likely to visit a general dental practitioner on a regular basis,38,39 and it could be argued that for this high-risk group, exposure to professional dental examination and advice is more likely to occur in a dental access centre setting.

This study has limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. Firstly, of the 1,294 patients who were eligible to participate in the study, data on consumption were available for 1,161 (89.7%). Data were not collected for all participants for a variety of reasons, for example, in a small number of cases the triage nurses felt the patient was too distressed to answer the questions relating to consumption and whether or not they had taken notice of the information campaign. In the majority of cases, however, data were excluded because the data sheets were not fully or accurately completed. An analysis of this missing data showed that cases not included were not different in terms of age or sex, with the median ages of excluded and included cases being very similar (33 years and 32 years) and a similar proportion of excluded cases being female (45% of excluded cases compared to 39% of included cases). This suggests that incomplete data were not more likely in men or women or younger or older participants, and so this might have only a minimal impact on the overall interpretation.

Some data were also missing for why participants had not read any of the information available. Again in a small number of cases the triage nurses felt it was inappropriate to ask the patients any further questions due to their pain, but in the majority of cases the data sheets were not fully completed. This is likely to reflect a degree of operator fatigue as the triage nurses were asked to complete the forms over a relatively long period. However, those who weren't asked why they had not read the information were very similar to both those who had given an answer and participants overall in terms of sex, age and consumption (median age of 32 and 38% female, low consumption 41% moderate 20% high or very high 39%) which suggests that the amount of missing data was similar across participants and not more likely in any particular group.

Of those patients giving a reason for not reading the information, the majority (almost 60%) had not seen or did not notice the posters or leaflets. This might improve with changes in the visual impact of the material. Similarly, the availability of information in a multilingual format, tailored to local community needs, may encourage uptake of information. Just over 10% did not read the information because of pain, and this will always be a difficulty in providing the information in this format to patients that have very immediate dental problems.

In common with many research projects40 it proved difficult to recruit patients to the qualitative element of this study, and as such the findings are based on interviews with nine patients. However, although a relatively small number, it does provide some evidence that the provision of information through a simple poster and leaflet format is likely to have limited impact. It is known that patients in this high-risk cohort can be extremely difficult to influence,41,42 and so health promotion in this group might pose significant challenges. As reported by Boyce et al., 'Influencing people's consumption of tobacco and alcohol requires a deeper understanding of why people behave as they do. It is about changing deep-rooted social habits that can become addictive, rather than just helping people make better choices as individuals'.43 Social marketing approaches, which involve developing an in-depth knowledge and understanding of the behaviour and beliefs of the target group, have been shown to be effective in promoting health behaviour change.44,45 Such approaches might then also be useful in developing health promotion campaigns around oral cancer.

Recent studies have shown that patient awareness of oral cancer can be influenced by a mass media approach46 and that oral cancer screening targeting high risk groups can be effective, particularly in recruiting patients to smoking cessation.47 Given the relatively poor survival rates for patients, cessation of tobacco use and moderation of alcohol use remain key elements in the fight against oral cancer.48 Government policy emphasises individual responsibility in adopting healthy behaviours and lifestyles and expects primary care trusts to commission support that will encourage people to change their behaviour to adopt more healthy lifestyles.49,50,51,52,53,54

This research confirms that dental access centres attract concentrated numbers of patients whose lifestyle habits place them at risk of developing oral cancer, and who can be readily identified as part of routine triaging processes. Dental access centres should therefore play a significant role in primary prevention, but the way in which patient information is provided requires further investigation. PCTs should invest in the development and provision of effective measures within dental access centres to provide opportunistic information about the risks of smoking and excess alcohol consumption to targeted cohorts of patients.

References

Scully C, Felix D H . Oral Medicine – update for the dental practitioner. Oral cancer. Br Dent J 2006; 200: 13–17.

Carter L M, Ogden G R . Oral cancer awareness of undergraduate medical and dental students. BMC Med Educ 2007; 7: 44.

Rosin M P, Poh C F, Elwood J M et al. New hope for an oral cancer solution: together we can make a difference. J Can Dent Assoc 2008; 74: 261–266.

West R, Alkhatib M N, McNeill A, Bedi R . Awareness of mouth cancer in Great Britain. Br Dent J 2006; 200: 167–169.

Petersen P E. Oral cancer prevention and control – the approach of the World Health Organisation. Oral Oncol 2008; 45: 454–460.

Johnson N. Tobacco use and oral cancer: a global perspective. J Dent Educ 2001; 65: 328–339.

Warnakulasuriya S. Causes of oral cancer – an appraisal of controversies. Br Dent J 2009; 207: 471–475.

Llewellyn C D, Johnson N W, Warnakulasuriya K A . Risk factors for oral cancer in newly diagnosed patients aged 45 years and younger: a case-control study in Southern England. J Oral Pathol Med 2004; 33: 525–532.

Llewellyn C D, Linklater K, Bell J, Johnson N W, Warnakulasuriya S . An analysis of risk factors for oral cancer in young people: a case-control study. Oral Oncol 2004; 40: 304–313.

Reichart P A. Identification of risk groups for oral precancer and cancer and preventive measures. Clin Oral Investig 2001; 5: 207–213.

Cancer Research UK. Oral cancer – UK incidence statistics. http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/types/oral/incidence/

Humphris G M, Duncalf M, Holt D, Field E A . The experimental evaluation of an oral cancer information leaflet. Oral Oncol 1999; 35: 575–582.

Downer M C, Moles D R, Palmer S, Speight P M . A systematic review of measures of effectiveness in screening for oral cancer and precancer. Oral Oncol 2006; 42: 551–560.

Kujan O, Glenny A M, Oliver R J, Thakker N, Sloan P . Screening programmes for the early detection and prevention of oral cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 3: CD004150.

Lim K, Moles D R, Downer M C, Speight P M . Opportunistic screening for oral cancer and precancer in general dental practice: results of a demonstration study. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 497–502.

McCann M F, McPherson L M, Gigson J . The role of the general dental practitioner in detection and prevention of oral cancer: a review of the literature. Dent Update 2000; 27: 404–408.

Ogden G R. Oral cancer prevention and detection in primary healthcare. Br Dent J 2003; 195: 263.

Warnakulasuriya K A, Harris C K, Scarrott D M et al. An alarming lack of public awareness towards oral cancer. Br Dent J 1999; 187: 319–322.

Lennon M A. Oral cancer – a survey of the general public. Br Dent J 1999; 187: 316.

Williams M, Scott S . Is there scope for providing oral cancer health advice in dental access centres? Br Dent J 2008: 205: E16.

Office for National Statistics. General Household Survey 2007. Available at http://www.statistics.gov.uk/downloads/theme_compendia/GHS07/GeneralHouseholdSurvey2007.zip.

Nottinghamshire Tobacco Control Strategy 2008-2012. A framework for action on tobacco control across Nottingham. Christine Harvey, James Thomas. January 2008. www.nottinghamshire.gov.uk/tobaccostrategydoc

West R, Zatonski W, Przewozniak K, Jarvis M J . Can we trust national smoking prevalence figures? Discrepancies between biochemically assessed and self-reported smoking rates in three countries. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2007; 16: 820–822.

Stockwell T, Donath S, Cooper-Stanbury M, Chikritzhs T, Catalano P, Mateo C . Under-reporting of alcohol consumption in household surveys: a comparison of quantity-frequency, graduated-frequency and recent recall. Addiction 2004; 99: 1024–1033.

Humphris G M, Ireland R S, Field E A . Immediate knowledge from an oral cancer information leaflet in patients attending a primary health care facility: a randomised controlled trial. Oral Oncol 2001; 37: 99–102.

Humphris G M, Field E A . An oral cancer information leaflet for smokers in primary care: results from two randomised controlled trials. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2004; 32: 143–149.

Humphris G M, Freeman R, Clarke H M . Risk perception of oral cancer in smokers attending primary care: a randomised controlled trial. Oral Oncol 2004; 40: 916–924.

Binnie W H, Cawson R A, Hill G B, Soaper A E . Studies on medical population subjects No 23. Oral cancer in England and Wales. A national study of morbidity, curability and related factors. London: HM Stationery Office, 1972.

Speight P M, Palmer S, Moles D R et al. The cost-effectiveness of screening for oral cancer in primary care. Health Technol Assess 2006; 10: 1–144.

Terrades M, Coulter W A, Clarke H, Mullally B H, Stevenson M . Patients' knowledge and views about the effects of smoking on their mouths and the involvement of their dentists in smoking cessation activities. Br Dent J 2009: 207: E22.

Johnson N W, Lowe J C, Warnakulasuriya K A . Tobacco cessation activities of UK dentists in primary care: Signs of improvement. Br Dent J 2006; 200: 85–89.

Rosseel J P, Jacobs J E, Hiberink S R et al. What determines the provision of smoking cessation advice and counselling by dental teams? Br Dent J 2009; 206: E13.

Csikar J, Williams S A, Beal J . Do smoking cessation activities as part of oral health promotion vary between dental care providers relative to the NHS/private treatment mix offered? A study in West Yorkshire. Prim Dent Care 2009; 16: 45–50.

Miller P M, Ravenel M C, Shaley A E, Thomas S . Alcohol screening in dental patients: the prevalence of hazardous drinking and patients' attitudes about screening and advice. J Am Dent Assoc 2006; 137: 1692–1698.

Dyer T A, Robinson P G . General health promotion in general dental practice – the involvement of the dental team Part 2: A qualitative and quantitative investigation of the views of practice principals in South Yorkshire. Br Dent J 2006; 201: 45–51.

Conway D I, Petticrew M, Marlborough H, Berthiller J, Hashibe M, Macpherson L M . Socioeconomic inequalities and oral cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Int J Cancer 2008; 122: 2811–2819.

Wanakulasuriya S. Significant oral cancer risk associated with low socioeconomic status. Evid Based Dent 2009; 10: 4–5.

Netuveli G, Sheiham A, Watt R G . Does the 'inverse screening law' apply to oral cancer screening and regular dental check ups? J Med Screen 2006; 13: 47–50.

Yusof Z Y, Netuveli G, Ramli A S, Sheiham A . Is opportunistic oral cancer screening by dentists feasible? An analysis of the patterns of dental attendance of a nationally representative sample over 10 years. Oral Health Prev Dent 2006; 4: 165–171.

Easterbrook P J, Matthews D R . Fate of research studies. J R Soc Med 1992; 85: 71–76.

Kerawala C J. Oral cancer, smoking and alcohol: the patients' perspective. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1999; 37: 374–376.

Fabian M C, Irish J C, Brown D H, Liu T C, Gullane P J . Tobacco, alcohol and oral cancer: the patient's perspective. J Otolaryngol 1996; 25: 88–93.

Boyce T, Robertson R, Dixon A. Commissioning and behaviour change: Kicking Bad Habits final report. London: Kings Fund 2008. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/kbh_final_report.html

Lowry R J, Hardy S, Jordan C, Wayman G . Using social marketing to increase recruitment of pregnant smokers to smoking cessation service: a success story. Public Health 2004; 118: 239–243.

Cohen D A, Farleey T A, Bedimo-Etanie J R et al. Implementation of condom social marketing in Louisiana, 1993 to 1996. Am J Public Health 1999; 89: 204–209.

Eadie D, MacKintosh A M, MacAskill S, Brown A . Development and evaluation of an early detection intervention for mouth cancer using a mass media approach. Br J Cancer 2009; 101(S2): S73–S79.

Nunn H, Lalli A, Fortune F, Croucher R . Oral cancer screening in the Bangladeshi community of Tower Hamlets: a social model. Br J Cancer 2009; 101 Suppl 2: S68–S72.

Muwange R, Ramadas K, Sankilla R et al. Role of tobacco smoking, chewing and alcohol drinking in the risk of oral cancer in Trivandrum, India: a nested case-control design using incident cancer cases. Oral Oncol 2008; 44: 446–454.

Department of Health. High quality care for all: NHS next stage review final report. London: Department of Health, 2008.

Department of Health. Securing our future health: Taking a long-term view - the Wanless report. London: Department of Health, 2002

Wanless D. Securing good health for the whole population: final report - February 2004. London: HM Treasury, 2004.

Department of Health. Choosing health: making healthy choices easier. London: Department of Health, 2004.

Department of Health. Our health, our care, our say: a new direction for community services. London: Department of Health, 2006.

Department of Health. Commissioning framework for health and well-being. London: Department of Health, 2007.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Cancer Research UK for providing the patient information leaflets used in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Williams, M., Bethea, J. Patient awareness of oral cancer health advice in a dental access centre: a mixed methods study. Br Dent J 210, E9 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.201

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.201

This article is cited by

-

Raising awareness of oral cancer from a public and health professional perspective

British Dental Journal (2018)

-

Oral cancer screening practices of oral health professionals in Australia

BMC Oral Health (2017)

-

Pilot study to train dentists to communicate about oral cancer: the impact on dentists' self-reported behaviour, confidence and beliefs

British Dental Journal (2016)