Abstract

Myelination defects in the central nervous system (CNS) are associated with various psychiatric disorders, including drug addiction. As these disorders are often observed in individuals prenatally exposed to cigarette smoking, we tested the hypothesis that such exposure impairs central myelination in adolescence, an important period of brain development and the peak age of onset of psychiatric disorders. Pregnant Sprague Dawley rats were treated with nicotine (3 mg kg−1 per day; gestational nicotine (GN)) or gestational saline via osmotic mini pumps from gestational days 4–18. Both male and female offsprings were killed on postnatal day 35 or 36, and three limbic brain regions, the prefrontal cortex (PFC), caudate putamen and nucleus accumbens, were removed for measurement of gene expression and determination of morphological changes using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) array, western blotting and immunohistochemical staining. GN altered myelin gene expression at both the mRNA and protein levels, with striking sex differences. Aberrant expression of myelin-related transcription and trophic factors was seen in GN animals, which correlated highly with the alterations in the myelin gene expression. These correlations suggest that these factors contribute to GN-induced alterations in myelin gene expression and also indicate abnormal function of oligodendrocytes (OLGs), the myelin-producing cells in the CNS. It is unlikely that these changes are attributable solely to an alteration in the number of OLGs, as the cell number was changed only in the PFC of GN males. Together, our findings suggest that abnormal brain myelination underlies various psychiatric disorders and drug abuse associated with prenatal exposure to cigarette smoke.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Maternal smoking during pregnancy (MSDP) has been associated with a number of neuropsychiatric disorders in the offspring, such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, depression, autism and drug addiction.1 Sexual dimorphism has been observed in MSDP-induced neuropsychiatric disorders. For example, boys exposed to MSDP are more likely to develop conduct disorder than nonexposed individuals, whereas girls showed a greater risk of becoming drug dependent.2 Adolescence is a critical period of brain development and the peak age of onset of psychiatric disorders,3, 4 and our recent studies have shown that gestational nicotine (GN) exposure impairs brain development during adolescence.5, 6

Myelin, a brain structure widely investigated decades ago,7 is attracting new interest because of its apparent involvement in drug addiction and various psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depression.8, 9 More interestingly, some recent studies have identified myelin as an important target of many psychotropic drugs.10, 11 Myelin is a membrane structure produced by oligodendrocytes (OLGs) in the central nervous system (CNS) and consists of many specific proteins and large amounts of glycolipids and cholesterol.7 The OLG–myelin complex has a critical role in the maintenance of brain function. In addition to increasing the conduction velocity of action potentials,12 the OLGs synthesize neurotrophic factors, support neuronal survival and modulate neurotransmission.13, 14, 15

Myelination in the CNS is a complex process involving OLG precursor migration, proliferation and differentiation into OLGs, followed by maturation and formation of a myelin sheath around the axons.7 This process is regulated by a combination of intrinsic programs and extrinsic factors, including transcription factors, neurotransmitters, trophic factors and cell adhesion molecules.16, 17, 18 Moreover, gonadal hormones are involved in this complicated process,19, 20 which may contribute to the known sex differences in OLG development, white matter maturation and pathology of myelin-related diseases.21, 22, 23

Although previous imaging studies showed abnormal white matter in smokers,24, 25 it is not clear whether MSDP affects brain myelination in the offspring. Given that both myelin defects and MSDP are related to the etiology of psychiatric diseases, we hypothesized that GN induces myelin abnormalities in adolescent brains. We evaluated the expression of a set of myelin-related genes in the brain regions critical in motor and motivation control. Given the potential sex differences, we evaluated both males and females. The number of OLGs and the factors regulating OLG development and myelination were examined to reveal potential mechanisms.

Considering the critical roles of the myelin–OLG complex in the brain, it is important to clarify the effect of MSDP on brain myelination, which may suggest an important mechanism underlying psychiatric disorders and drug abuse in adolescents exposed to cigarette smoking prenatally. By considering age and sex, two critical factors in the development of psychiatric disorders, our study provides a thorough evaluation of the myelin gene expression. Given that myelin is a potential target of psychotropic therapies, this information will help in the development of more efficient treatment and prevention strategies for psychiatric disorders and drug addiction.

Materials and methods

Animals and tissue collection

Sprague Dawley rats were maintained in a temperature (21 °C)- and humidity (50%)-controlled room on a 12-h light–dark cycle (lights on 0700–1900 h) with unlimited access to food and water. Pregnant rats (Harlan, San Diego, CA, USA) were treated with nicotine or saline as previously described.26 Each dam was given either nicotine at a concentration of 3 mg kg−1 per day (calculated free base) or saline via an osmotic minipump (Alzet Model 2002, Durect, Cupertino, CA, USA, flow rate 51 μl per day) with a 14-day delivery period starting from gestational day 4. The minipump was implanted subcutaneously on the back of each dam. Blood concentrations resulting from this dose of nicotine are equivalent to those found in humans who smoke about one and a half packs of cigarettes per day.27 After birth, pups were cross-fostered on non-drug-exposed mothers to minimize the effects of abnormal maternal behaviors or milk output attributable to nicotine treatment. As previously reported,28 GN treatment did not influence dam weight gain, litter size or pup weight gain during postnatal development. Pups were weaned on postnatal day (P) 21, and for each gender, nonsibling animals were used in each experiment. Adolescence in rats was defined as the fifth and sixth postnatal weeks.3 Pups aged P35 were decapitated, and tissues were collected from the prefrontal cortex (PFC), caudate putamen (CPu) and nucleus accumbens (NAc). The tissues were excised using a brain punch tissue set (Stoelting, Wood Dale, WI, USA) and rat brain matrices (Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT, USA) according to coordinates from Paxinos and Watson.29 The location of each brain region examined in this study is shown in Figure 1. Tissue punches were stored at −80 °C until use for qRT-PCR assay (N=5 or 6) or western blotting (N=3 or 4). Animals for immunohistology staining were killed at P35–36 by an overdose of pentobarbital administered intraperitoneally, followed by transcardial perfusion with phosphate-buffered 4% paraformaldehyde with 4% sucrose (N=3 or 4). Brains were extracted, kept in fixative at 4 °C overnight and stored in phosphate-buffered saline until sectioning done at the NeuroScience Associates (Knoxville, TN, USA). All experiments were carried out in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of California at Irvine, Irvine, CA, USA, and University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA, and were consistent with the Federal guidelines.

qRT-PCR array

After reviewing the myelin components and factors regulating OLG development and myelin formation,7, 18, 30 we examined genes encoding 11 major myelin proteins, 4 lipid-related enzymes, 9 myelin-related transcription factors and 8 trophic factor-related proteins using qRT-PCR. The primers were designed using Primer Express (v. 3.0) software (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and spanned introns to avoid amplifying genomic DNA. The amplicon sequences were subjected to a BLAST search to ensure the specificity of the primers for the target gene and were synthesized by Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). All the primers were tested for their specificity by checking the cycle number and the dissociation curve before inclusion in the qRT-PCR array. The primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S1. RNA was isolated from each brain region using TRIZol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and was amplified as described previously for adequate cDNA probe labeling.5 The qRT-PCR was conducted as described previously.31, 32 Briefly, the RT product was amplified in a volume of 10 μl containing 5 μl of 2 × Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and a combination of sense and antisense primers (3 μl; final concentration 250 nM) in a 384-well plate using the 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). Expressions of all genes were normalized to the expression of actin and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, and then analyzed using a comparative Ct method.33 As data normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase yielded results very similar to those normalized by actin, only the results normalized by actin are provided in this report.

Western blotting assay

Tissue punches were homogenized in ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer (50 mM Tris Cl, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate and 0.1% SDS) with protease inhibitor (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The protein concentrations of the lysates were determined using the Bio-Rad assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Five micrograms of protein from each sample was loaded in 15% resolving gels with 5% stacking gels and was separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The separated proteins were transferred electrophoretically to nitrocellulose membranes (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) for 1 h at 100 V at room temperature. The membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature with 1% bovine serum albumin dissolved in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 2000 buffer and incubated overnight with mouse anti-myelin basic protein (MBP), a.a. 129–138 monoclonal antibody (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA; 1:500) at 4 °C. Membranes were washed three times for 10 min each in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 2000 buffer and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with secondary antibodies (1:5000; anti-mouse IgG, horseradish peroxidase labeled (PerkinElmer)). The hybridized membranes were washed with Tris-buffered saline with Tween 2000 buffer three times for 10 min each, and the immunoreactivity of the proteins was detected using Western Lightning Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus (PerkinElmer) and exposure to X-ray film. Tubulin protein was used as an internal control for discrepancies in the loading of proteins in each lane. A mouse monoclonal antibody to α-tubulin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), was used as the primary antibody (1:2000) and an anti-mouse IgG as the secondary antibody in western blotting for tubulin.

Immunohistochemistry

Brains received at the NeuroScience Associates were treated with 20% glycerol and 2% dimethylsulfoxide, and were embedded in a gelatin matrix using MultiBrain Technology (NeuroScience Associates). The MultiBrain blocks of embedded brains were frozen and sectioned in the coronal plane at 30 μm on an AO 860 sliding microtome (IMEB, North Andover, MA, USA). Sections were collected into Antigen Preserve solution (50% ethylene glycol, 49% phosphate-buffered saline pH 7.0, 1% polyvinyl pyrrolidone). After blocking by hydrogen peroxide and nonimmune serum, the sections were immunostained with a primary antibody overnight at room temperature. SMI-99 (Covance, Princeton, NJ, USA, SMI-99p, 1:5000 dilution), an antibody against MBP, was used to identify myelinated fibers. Olig2 (1:500 dilution) immunohistology was used to identify OLG cell bodies. Following washing, sections were incubated in a biotinylated secondary antibody for 2 h at room temperature. After additional washes, sections were incubated in an avidin–biotin–horseradish peroxidase complex for 1 h at room temperature (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). The sections were developed with diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride and hydrogen peroxide, and were mounted on gelatinized glass slides. After being dehydrated in a standard alcohol series, the slides were coverslipped with Permount.

Image capture and analysis

The sections analyzed in the imaging-related experiment were comparable to those quantified in qRT-PCR (Figure 1). Images of CPu were captured on a Nikon 90i microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) using an objective with × 10 magnification and NIS Elements BR 2.30 software (Nikon) at the highest resolution (4116 × 3072). Images of the PFC were captured using an objective with a × 20 magnification.

The images were opened in Photoshop CS5, converted to grayscale and were inverted. This produced an image with a dark background and light myelin, and a positive number for optical density. Eight measurements of optical density in the PFC were taken from one section for each brain. Specifically, one column of four measurements was on the lateral end of the prelimbic cortex, and one column of four measurements as from the midline of the prelimbic cortex. Myelin staining was virtually absent in proximity to the central sulcus. The average of the eight measurements was calculated, and the values were compared. For the CPu, 10 measurements were taken from random locations between the fiber bundles in the dorsal part of CPu in each brain, and the average was calculated. The integrated optical density of the fiber bundles and the average bundle size in the same locations were further analyzed using Image J (rsb.info.nih.gov/ij). Two levels of the CPu 180 μm apart in the rostral–caudal axis were analyzed, and the averages from the two levels for each brain were calculated and compared.

For the Olig2 staining, cell numbers were counted using Image J with background subtracting at 100 pixels and particle size as 20–50 pixel units. For each brain, cell numbers at two levels 180 μm apart in the rostral–caudal axis were quantified, and the average was calculated for further comparison.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed by mixed-design analysis of variance with between-subject factors (age, sex, brain region and drug) and a within-subject factor (gene). Significant main effects and interactions were further analyzed by appropriate analysis of variance and post-hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Significant alteration in mRNA expression was defined as a fold change >20% with a P-value <0.05.

Results

mRNA expression of major myelin genes and protein expression of Mbp in the PFC

GN significantly altered myelin gene expression in the PFC in a sex-dependent way. In males (Figure 2a), GN increased the expression of Mbp, myelin-associated oligodendrocytic basic protein (Mobp), proteolipid protein 1 (Plp1), myelin-associated glycoprotein (Mag), gap junction membrane channel protein epsilon 1 (Gje1), gap junction protein alpha 12, 47 kDa (Gjc2) and claudin 11 (Cldn11; P<0.05 for each gene). In contrast, all genes except Gjc2 were significantly downregulated in GN females (Figure 2b; P<0.01 for Mbp, Cnp, Mag, Mog, Mal and Cldn11; P<0.05 for Mobp, Plp1, Gje1, Gjb1). The GN treatment had no effects on glial fibrillary acidic protein (Gfap), chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 (Cspg4) or ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba1), the markers for astrocytes, synantocytes and microglia, respectively, in either males or females (Figures 2c and d).

Fold change in mRNA expression of major myelin genes and protein expression of myelin basic protein (MBP) in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of adolescent animals treated with gestational nicotine (GN; black bars) or saline (GS; white bars). Eleven major myelin genes (a, b) with glial fibrillary acidic protein (Gfap), chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 (Cspg4) and ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba1), the markers for astrocytes, synantocytes and microglia, respectively (c, d) were examined by quantitative real-time PCR in both males (a, c) and females (b, d) (N=5 or 6). The three-way mixed-design analysis of variance with two between-subject factors (that is, sex and drug) and one within-subject factor (that is, gene) showed a significant sex effect (F1, 17=7.893; P=0.012) and interaction of sex and drug (F1, 17=7.901; P=0.012). Expression of MBP protein was evaluated by western blotting. (e) Representative images for MBP and tubulin. (f) Fold change of MBP in GN animals compared with GS animals after normalization to tubulin (N=3 or 4). Data are expressed as means±s.e.m. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 significantly different from GS. Mobp, myelin-associated oligodendrocytic basic protein; Plp1, proteolipid protein 1; Cnp, 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′ phosphodiesterase; Mag, myelin-associated glycoprotein; Mog, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein; Mal, T-cell differentiation protein; Gje1, gap junction membrane channel protein epsilon 1; Gjc2, gap junction protein, alpha 12, 47kDa; Gjb1, gap junction protein, beta 1; Cldn11, claudin 11.

MBP is the second most abundant CNS myelin protein and is critical in maintenance of the myelin sheaths.34 Deficits in MBP expression lead to an overall downregulation of other myelin protein expression.35 Therefore, we selectively examined MBP protein expression. Consistent with the modifications seen at the mRNA level, we found that Mbp was upregulated in GN males but downregulated in GN females (Figures 2e and f).

mRNA expression of myelin lipid-related enzymes in the PFC

Given that the myelin structure is characterized by large amounts of lipids, we evaluated the mRNA expression of three enzymes involved in lipid synthesis, namely, UDP glycosyltransferase 8 (Ugt8), aspartoacylase (Aspa) and farnesyl diphosphate farnesyl transferase 1 (Fdft1). We also evaluated the expression of galactosylceramidase (Galc), which catalyzes the hydrolytic cleavage of galactose from galactocerebroside (Figure 3). GN exposure significantly altered gene expression in a sex-dependent way. Both Ugt8 (P<0.05) and Aspa (P<0.01) were significantly upregulated by GN in the PFC of males (Figure 3a).

Fold change in mRNA expression of myelin lipid-related enzymes in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of adolescent animals treated with gestational nicotine (GN; black bars) or saline (GS; white bars). Four genes, UDP glycosyltransferase 8 (Ugt8), aspartoacylase (Aspa), farnesyl diphosphate farnesyl transferase 1 (Fdft1) and galactosylceramidase (Galc), were evaluated using quantitative real-time PCR in both males (a) and females (b). The three-way mixed-design analysis of variance with two between-subject factors (that is, sex and drug) and one within-subject factor (that is, gene) showed a significant sex effect (F1, 17=11.458, P=0.004) and an interaction of sex and drug (F1, 17=15.901; P=0.001). Data are expressed as means±s.e.m. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 significantly different from GS (N=5 or 6).

mRNA expression of myelin genes in the striatum

We further evaluated mRNA expression of myelin genes in the striatum, including the CPu and NAc. The GN treatment significantly modified the myelin gene expression in the striatum in a sex-dependent manner (Table 1). In the CPu, all examined genes except Gje1, Gjb1 and Fdft1 were significantly upregulated in GN males (P<0.01 for Cldn11, Mal and Gjc2; P<0.05 for Mbp, Mobp, Plp1, Cnp, Mag, Mog, Ugt8, Aspa and Galc). None of these genes was significantly modified in GN females. In the NAc, Mbp, Mobp, Plp1, Cnp, Mog, Gjb1 and Ugt8 were upregulated in GN males (P<0.05 for each gene), whereas only Mbp and Plp1 were upregulated in GN females (P<0.05 for each gene). In contrast, neither Cspg4 nor Iba1 was affected by GN in any brain region, whereas Gfap was upregulated only in the CPu of GN males (P<0.01).

MBP immunohistology

The MBP staining showed fine fibers in the PFC (Figures 4a–d). The GN males had denser myelinated fibers, whereas GN females had fewer myelinated fibers, compared with the gestational saline (GS) the rats. These findings were confirmed by quantification of the optical density, which showed a significant interaction of sex and drug (F1, 8=5.753; P<0.05) and a significant increase in GN males compared with GS males (P<0.05; Figure 4e). The MBP staining in the CPu showed large fiber bundles with fine fibers in between (Figures 4f–i). The optical densities of the fine fibers were not changed in either males (GN: 66±0.7; GS: 67.0±1.9) or females (GN: 65.1±0.9; GS: 63.9±0.3). However, the integrated optical density of the fiber bundles was significantly higher in GN males (P<0.05) than in control males (Figure 4J). Given the similar optical density, the integrated optical density reflects an increase in the average bundle size in GN males (GN: 12 575.5±274.1; GS: 10 798.1±297.0, P<0.05).

Immunohistology staining for myelin basic protein (MBP) in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and caudate putamen (CPu) of adolescent animals. Representative images were captured from the PFC (a–d) and CPu (f–i) from both male and female rats exposed to gestational nicotine (GN) or saline (GS). Optical density in the PFC (e) and integrated optical density (optic density × average bundle size) in the CPu (j) were quantified and compared in GN (black bars) and GS (white bars) animals. The two-way analysis of variance showed a significant interaction of sex and drug (F1, 8=5.753; P<0.05). Data are expressed as means±s.e.m. (N=3 or 4). *P<0.05 significantly different from GS.

mRNA expression of transcription factors

Given that the expression of myelin genes was altered at the mRNA level, we assayed the mRNA expression of nine transcription factors that regulate the myelin gene expression (Figure 5). As CPu and NAc showed a similar pattern of modification, we examined only the expression of transcription factors in the PFC and CPu. The GN treatment significantly modified the expression of these genes in a brain region- and sex-dependent manner. In the PFC, GN increased the expression of OLG transcription factor-1 (Olig1; P<0.01), Olig2 (P<0.001), Olig3 (P<0.01) and SRY box 10 (Sox10; P<0.05) in males (Figure 5a), whereas GN decreased the expression of Olig3 (P<0.05), Sox10 (P<0.05) and NK6 homeobox 2 (Nkx6-2; P<0.01) in females (Figure 5b). In the CPu, GN increased the expression of Olig1, Olig2, SRY box 8 (Sox8), SRY box 9 (Sox9), Sox10, NK2 transcription factor-related locus 2 (Nkx2-2) and Nkx6-2 in males (Figure 5c), whereas GN increased the expression only of Sox9 in females (P<0.05 for each gene; Figure 5d).

Fold change in mRNA expression of transcription factors in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) (a, b) and caudate putamen (CPu) (c, d) of adolescent rats exposed to gestational nicotine (GN; black bars) or saline (GS; white bars). The four-way mixed-design analysis of variance with three between-subject factors (that is, sex, brain region and drug) and one within-subject factor (that is, gene) showed significant effects of drug (F1, 36=42.834; P<0.001) and sex (F1, 36=37.246; P<0.001), and an interaction of brain region with drug and sex (F1, 36=10.719; P=0.002). Data are expressed as means±s.e.m. (N=4 or 5). *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001 significantly different from GS. Olig1, Olig2 and Olig3: oligodendrocyte transcription factor-1, 2 and 3; Sox8, Sox9 and Sox10: SRY box 8, 9 and 10; Nkx2-2, NK2 transcription factor related, locus 2; Nkx6-2, NK6 homeobox 2; Myt1, myelin transcription factor-1.

mRNA expression of trophic factors

Considering that trophic factors have an important role in OLG development and myelin formation, we assayed the mRNA expression of eight trophic factors in the PFC and CPu (Table 2). The GN treatment significantly modified the expression of these factors. In the PFC, GN increased the expression of insulin-like growth factor-1 (Igf1; P<0.001), ciliary neurotrophic factor (Cntf; P<0.05) and transferrin (Tf; P<0.05) in males, but decreased the expression of Tf and v-erb-b2 erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 3 (Erbb3) in females (P<0.05). In the CPu (Table 2), GN increased the expression of Erbb3, beta-site APP-cleaving enzyme 1 (Bace1), neurotrophin 3 (Ntf3) and Tf in males (P<0.05 for each gene), whereas GN increased the expression of Erbb3 in females (P<0.01).

Determination of number of OLGs

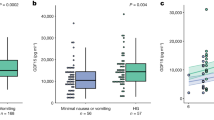

To examine whether the alteration in myelin gene expression is secondary to a change in the number of OLGs, we determined the number of OLGs in both the PFC and CPu. The number of OLGs was increased in the PFC of GN male rats (see Figures 6a; P<0.05 for all of them) but not in the females (Figures 6c–e). In contrast, the number of OLGs in the CPu was not changed in either males (GS: 7580±137; GN: 7953±134 per mm2) or females (GS: 7628±170; GN: 8208±321 per mm2).

Immunohistology staining for oligodendrocyte transcription factor 2 (Olig2) in adolescent prefrontal cortex (PFC). Representative images (a–d) were captured from PFC of male and female rats exposed to gestational nicotine (GN) or saline (GS). The cell numbers were quantified (e) and compared in GN (black bars) and GS (white bars) animals. Data are expressed as means±s.e.m. (N=3 or 4). *P<0.05 significantly different from GS.

Discussion

Brain myelin has recently received increased attention, as it provides a common mechanism for various psychiatric disorders and addictions, and a potential target for psychotropic treatments. Although many studies have shown the effects of GN on the CNS,36, 37 it is not clear whether GN alters central myelination. We found that GN altered the expression of a number of genes involved in myelination in adolescent brains, with sex and brain region differences, indicating that GN disturbs OLG development and myelin formation. The abnormal expression of myelin-related transcription and trophic factors correlated with that of myelin genes, suggesting that these factors are involved in GN-induced alteration in myelin gene expression and may also reflect the abnormal functions of OLGs. These changes are not attributable solely to a change in OLG proliferation or turnover, as the number of OLG was changed only in the PFC of GN males. Given that defects in central myelination have been observed in various psychiatric disorders and drug abuse,38 MSDP might increase the risks of these diseases in the offspring by disturbing OLG development and myelination in the CNS.

GN altered the myelin gene expression in adolescents with brain region and sex differences

The GN treatment modified mRNA expression of a number of genes encoding major myelin proteins. Among these genes, MBP is critical in maintaining myelin structure, and deficits in MBP expression lead to an overall downregulation of other myelin protein expression.7, 35 Therefore, we confirmed that MBP protein expression was changed in the PFC by GN treatment, and MBP immunohistology investigation suggested abnormal myelin formation in both the PFC and the CPu of GN animals. Knockout of some myelin genes, such as Plp, Mag or Cnp, leads to axonal swelling followed by neuronal degeneration.14 Therefore, modifications of these genes may influence neuronal survival. We have previously shown that GN changes apoptosis pathways in the limbic system of female adolescents,6 which may be attributable to the myelin abnormalities. In addition, deficits in connexin expression (Gje1, Gjc2 and Gjb1) suggest abnormal interactions between OLGs and astrocytes.39 In addition to the genes encoding major myelin proteins, the expression of enzymes involved in lipid synthesis and metabolism were changed by GN, which further suggests abnormalities in myelin structure and function. Recent study of human tissues suggests that prenatal exposure to nicotine leads to abnormal glial development.40 We showed that the markers of other glial cells expressed normally in most brain regions of GN rats, which suggests that GN has a stronger effect on OLGs than on other glial cells.

The alteration of myelin gene expression at the mRNA, protein and morphologic levels suggests that GN changes central myelination in adolescents. Brain maturation during adolescence is characterized by increased myelination, especially in the PFC.41 Consistent with the brain-region differences in development, we found that GN increased the expression of myelin genes in GN males, with more affected genes and higher fold changes in the PFC than in other brain regions. Interestingly, GN had the opposite effect on myelin gene expression in the PFC of females. This observation suggests that GN enhances the active myelination process in adolescent male animals but decreases it in females. Although myelin gene expression appeared normal in the CPu of females, this effect is likely to be temporary, as we observed a general decrease in the expression of these genes in the CPu of adult females prenatally exposed to nicotine (data not shown). We also observed abnormal myelin gene expression in the NAc in both adolescent males and females, which showed a pattern similar to that in the CPu. However, the two major myelin proteins, MBP and PLP, were modified in the NAc but not in the CPu of adolescent females, suggesting that myelination in the ventral striatum of females is more vulnerable to GN. Given that dysfunctions of these brain regions are involved in many psychiatric disorders,42, 43 myelin abnormalities in these regions may shed light on the link between MSDP and neurobehavioral problems in the offspring. A decrease in myelin gene expression in the cortex and striatum has been observed in drug abusers and patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder.38 The downregulation of myelin genes in GN females implies that girls whose mothers smoked during pregnancy are susceptible to these disorders. In fact, girls exposed to maternal smoking prenatally have a greater risk of becoming drug dependent than nonexposed individuals.2 Although the consequences of upregulation of myelin gene expression in males are not clear, there are studies showing overexpression of myelin genes, such as Plp and Cnp, leading to striking aberrant myelin sheath.44, 45, 46, 47 It also has been suggested that hypermyelination leads to cognitive problems.48 We observed abnormal myelin gene expression in juveniles and adults (data not shown); however, the pattern of modification is significantly different from that in adolescents. This observation correlates with the fact that adolescence is a period of vulnerability to many psychiatric disorders and drug abuse,4, 49, 50, 51 which further indicates that myelin deficits are related to MSDP-induced psychiatric disorders.

Potential mechanisms

The mechanisms underlying the effect of gestational nicotine treatment on adolescents are complicated. As these animals were exposed to nicotine only during prenatal development, the effect on myelin gene expression in adolescents is likely due to a direct effect of nicotine on fetal development, which leads to subsequently disruption of the brain development during adolescence. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are expressed on OLG precursors but not in differentiated OLG.52 Although very limited studies examined the functions of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on OLG precursors, our pilot study has suggested that nicotine can induce OLG precursor proliferation (data not shown). On the other hand, nicotine has indirect effects on OLG development, such as by altering neurotransmission and trophic factor expression. We showed that the number of OLGs was increased in the PFC of GN males, which may contribute to the increased myelin gene expression detected. Given that Cspg4, the marker of the OLG precursor, was not changed in the PFC, the alteration in the number of OLGs could be secondary to a decrease in cell turnover or an increase in cell proliferation at an earlier age. In contrast to the male PFC, the cell number was not changed in the PFC of females or in the CPu of males in which the gene expression was altered. These findings suggest that GN changes myelin production, but not cell proliferation or turnover, in these groups. In general, abnormal myelin gene expression is attributable to more than a change in cell numbers.

The sex and brain region differences may be related to gonadal hormones. Gonadal hormones stimulate OLG development and myelination.19, 53 They also contribute to the brain region-dependent sexual dimorphism in white matter development during adolescence.54 Puberty is characterized by a dramatic change in gonadal hormone levels and starts around P35 in rats, at which time our adolescent animals were examined. It has been suggested that GN delays the onset of puberty in female animals,55 whereas early onset of puberty in males has been linked to MSDP.56 Therefore, gonadal hormones may contribute to the opposite sex differences observed in the PFC with GN treatment. Future studies on gonadal hormone concentrations in this animal model will help to answer this question.

In addition to the involvement of gonadal hormones, both OLG development and myelin formation are regulated by intrinsic programs, such as transcriptional regulation, and also by extrinsic factors, including trophic factors.57

Transcription factors

All the transcription factors examined positively modulate myelin gene expression.30 The changes in the expression of these transcriptional factors are in the same direction as those of myelin gene expression. The correlations between the modifications of myelin gene expression and transcription factors support the view that transcription factors function as networks to regulate myelin gene expression.30

Trophic factors

The neuregulin system and growth factors have important roles in OLG development and myelination.17 We showed that GN modified the expression of Erbb3, one of the neuregulin receptors, BACE1, an aspartyl protease involved in the proteolysis of neuregulin, and Cntf, Ntf3 and Igf1, which may further contribute to GN-induced myelin abnormalities. As no gene was predominantly responsible for the myelin abnormalities in all the groups, growth factors may regulate myelination in a brain region- and sex-dependent manner. Moreover, Tf, an iron transporter critical in OLG maturation and myelination,58 was modified by GN in a way similar to that of myelin genes. Given the existence of both extracellular and intracellular forms,59 Tf may serve as both an intrinsic and an extrinsic regulation factor in GN-induced myelin abnormality.

Although there is no direct evidence to support the view that GN alters myelin gene expression by changing transcription factors and trophic factors, the correlations strongly suggest that these genes are involved in GN-induced myelin deficits. On the other hand, OLGs also synthesize these trophic factors,13 and most of the transcriptional factors examined are highly expressed in OLGs. Therefore, the alteration in expression of these genes suggests abnormal function of OLGs.

Conclusions

Our data clearly show that GN altered central myelin gene expression in adolescents, with sex and brain-region differences. Although the exact regulatory mechanisms remain to be characterized, our findings showed that the change in myelin-related transcription and trophic factors is correlated with that in myelin genes. The abnormal expression of transcription and trophic factors also suggests functional defects in the OLG–myelin complex. Our results therefore offer a mechanism underlying psychiatric disorders and drug abuse associated with MSDP. Considering the critical roles of myelin in the brain, the abnormal myelin gene expression further suggests some unknown neurological problems related to MSDP. Finally, the striking sex differences imply a need for different psychotropic therapies for male and female subjects.

References

Knopik VS . Maternal smoking during pregnancy and child outcomes: real or spurious effect? Dev Neuropsychol 2009; 34: 1–36.

Weissman MM, Warner V, Wickramaratne PJ, Kandel DB . Maternal smoking during pregnancy and psychopathology in offspring followed to adulthood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999; 38: 892–899.

Spear LP . The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2000; 24: 417–463.

Paus T, Keshavan M, Giedd JN . Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat Rev Neurosci 2008; 9: 947–957.

Cao J, Dwyer JB, Mangold JE, Wang J, Wei J, Leslie FM et al. Modulation of cell adhesion systems by prenatal nicotine exposure in limbic brain regions of adolescent female rats. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2011; 14: 157–174.

Wei J, Wang J, Dwyer JB, Mangold J, Cao J, Leslie FM et al. Gestational nicotine treatment modulates cell death/survival-related pathways in the brains of adolescent female rats. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2011; 14: 91–106.

Baumann N, Pham-Dinh D . Biology of oligodendrocyte and myelin in the mammalian central nervous system. Physiol Rev 2001; 81: 871–927.

Bora E, Yucel M, Fornito A, Pantelis C, Harrison BJ, Cocchi L et al. White matter microstructure in opiate addiction. Addict Biol 2012; 17: 141–148.

Fields RD . White matter in learning, cognition and psychiatric disorders. Trends Neurosci 2008; 31: 361–370.

Bartzokis G . Neuroglialpharmacology: white matter pathophysiologies and psychiatric treatments. Front Biosci 2012; 17: 2695–2733.

Eschenroeder AC, Vestal-Laborde AA, Sanchez ES, Robinson SE, Sato-Bigbee C . Oligodendrocyte responses to buprenorphine uncover novel and opposing roles of mu-opioid- and nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptors in cell development: implications for drug addiction treatment during pregnancy. Glia 2012; 60: 125–136.

Hursh JB . Conduction velocity and diameter of nerve fiber. Am Physiol Soc 1939; 127: 131–139.

Du Y, Dreyfus CF . Oligodendrocytes as providers of growth factors. J Neurosci Res 2002; 68: 647–654.

Nave KA, Trapp BD . Axon-glial signaling and the glial support of axon function. Annu Rev Neurosci 2008; 31: 535–561.

Roy K, Murtie JC, El-Khodor BF, Edgar N, Sardi SP, Hooks BM et al. Loss of erbB signaling in oligodendrocytes alters myelin and dopaminergic function, a potential mechanism for neuropsychiatric disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104: 8131–8136.

Belachew S, Rogister B, Rigo JM, Malgrange B, Moonen G . Neurotransmitter-mediated regulation of CNS myelination: a review. Acta Neurol Belg 1999; 99: 21–31.

Laursen LS, Ffrench-Constant C . Adhesion molecules in the regulation of CNS myelination. Neuron Glia Biol 2007; 3: 367–375.

Melli G, Hoke A . Canadian Association of Neurosciences review: regulation of myelination by trophic factors and neuron-glial signaling. Can J Neurol Sci 2007; 34: 288–295.

Kafitz KW, Herth G, Bartsch U, Guttinger HR, Schachner M . Application of testosterone accelerates oligodendrocyte maturation in brains of zebra finches. Neuroreport 1992; 3: 315–318.

Schumacher M, Guennoun R, Stein DG, De Nicola AF . Progesterone: therapeutic opportunities for neuroprotection and myelin repair. Pharmacol Ther 2007; 116: 77–106.

Cerghet M, Skoff RP, Bessert D, Zhang Z, Mullins C, Ghandour MS . Proliferation and death of oligodendrocytes and myelin proteins are differentially regulated in male and female rodents. J Neurosci 2006; 26: 1439–1447.

Perrin JS, Herve PY, Leonard G, Perron M, Pike GB, Pitiot A et al. Growth of white matter in the adolescent brain: role of testosterone and androgen receptor. J Neurosci 2008; 28: 9519–9524.

Czlonkowska A, Ciesielska A, Gromadzka G, Kurkowska-Jastrzebska I . Estrogen and cytokines production - the possible cause of gender differences in neurological diseases. Curr Pharm Des 2005; 11: 1017–1030.

Lin F, Wu G, Zhu L, Lei H . Heavy smokers show abnormal microstructural integrity in the anterior corpus callosum: A diffusion tensor imaging study with tract-based spatial statistics. Drug Alcohol Depend 2012; 129: 82–87.

Kim JK, Choi JW, Lim S, Kwon O, Seo JK, Ryu SH et al. Phospholipase C-eta1 is activated by intracellular Ca(2+) mobilization and enhances GPCRs/PLC/Ca(2+) signaling. Cell Signal 2011; 23: 1022–1029.

Park MK, Loughlin SE, Leslie FM . Gestational nicotine-induced changes in adolescent neuronal activity. Brain Res 2006; 1094: 119–126.

Matta SG, Elberger AJ . Combined exposure to nicotine and ethanol throughout full gestation results in enhanced acquisition of nicotine self-administration in young adult rat offspring. Psychopharmacology 2007; 193: 199–213.

Franke RM, Belluzzi JD, Leslie FM . Gestational exposure to nicotine and monoamine oxidase inhibitors influences cocaine-induced locomotion in adolescent rats. Psychopharmacology 2007; 195: 117–124.

Paxinos G, Watson C 2005 The Rat Brain in Stereotxic Coordinates. Academic Press Inc.: San Diego.

Wegner M . A matter of identity: transcriptional control in oligodendrocytes. J Mol Neurosci 2008; 35: 3–12.

Gutala R, Wang J, Kadapakkam S, Hwang Y, Ticku M, Li MD . Microarray analysis of ethanol-treated cortical neurons reveals disruption of genes related to the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and protein synthesis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2004; 28: 1779–1788.

Li MD, Kane JK, Wang J, Ma JZ . Time-dependent changes in transcriptional profiles within five rat brain regions in response to nicotine treatment. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 2004; 132: 168–180.

Winer J, Jung CK, Shackel I, Williams PM . Development and validation of real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction for monitoring gene expression in cardiac myocytes in vitro. Anal Biochem 1999; 270: 41–49.

Readhead C, Takasashi N, Shine HD, Saavedra R, Sidman R, Hood L . Role of myelin basic protein in the formation of central nervous system myelin. Ann NY Acad Sci 1990; 605: 280–285.

Carre JL, Goetz BD, O'Connor LT, Bremer Q, Duncan ID . Mutations in the rat myelin basic protein gene are associated with specific alterations in other myelin gene expression. Neurosci Lett 2002; 330: 17–20.

Dwyer JB, McQuown SC, Leslie FM . The dynamic effects of nicotine on the developing brain. Pharmacol Ther 2009; 122: 125–139.

Pauly JR, Slotkin TA . Maternal tobacco smoking, nicotine replacement and neurobehavioural development. Acta Paediatr 2008; 97: 1331–1337.

Sokolov BP . Oligodendroglial abnormalities in schizophrenia, mood disorders and substance abuse. Comorbidity, shared traits, or molecular phenocopies? Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2007; 10: 547–555.

Menichella DM, Goodenough DA, Sirkowski E, Scherer SS, Paul DL . Connexins are critical for normal myelination in the CNS. J Neurosci 2003; 23: 5963–5973.

Chang L, Cloak CC, Jiang CS, Hoo A, Hernandez AB, Ernst TM . Lower glial metabolite levels in brains of young children with prenatal nicotine exposure. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2012; 7: 243–252.

Matsuoka T, Sumiyoshi T, Tsunoda M, Takasaki I, Tabuchi Y, Uehara T et al. Change in the expression of myelination/oligodendrocyte-related genes during puberty in the rat brain. J Neural Transm 2010; 117: 1265–1268.

Drevets WC, Price JL, Furey ML . Brain structural and functional abnormalities in mood disorders: implications for neurocircuitry models of depression. Brain Struct Funct 2008; 213: 93–118.

Feltenstein MW, See RE . The neurocircuitry of addiction: an overview. Br J Pharmacol 2008; 154: 261–274.

Karim SA, Barrie JA, McCulloch MC, Montague P, Edgar JM, Kirkham D et al. PLP overexpression perturbs myelin protein composition and myelination in a mouse model of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. Glia 2007; 55: 341–351.

Anderson TJ, Klugmann M, Thomson CE, Schneider A, Readhead C, Nave KA et al. Distinct phenotypes associated with increasing dosage of the PLP gene: implications for CMT1A due to PMP22 gene duplication. Ann NY Acad Sci 1999; 883: 234–246.

Gravel M, Peterson J, Yong VW, Kottis V, Trapp B, Braun PE . Overexpression of 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phosphodiesterase in transgenic mice alters oligodendrocyte development and produces aberrant myelination. Mol Cell Neurosci 1996; 7: 453–466.

Yin X, Peterson J, Gravel M, Braun PE, Trapp BD . CNP overexpression induces aberrant oligodendrocyte membranes and inhibits MBP accumulation and myelin compaction. J Neurosci Res 1997; 50: 238–247.

Quaranta L, Sabatelli M, Madia F, Ricci E, Lippi G, Conte A et al. Expanding the nosology of hypermyeliating neuropathies: description of two new entities. J Peripheral Nervous Syst 2002; 7: 82–83.

Biederman J, Mick E, Faraone SV . Age-dependent decline of symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: impact of remission definition and symptom type. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157: 816–818.

Peterson BS . Considerations of natural history and pathophysiology in the psychopharmacology of Tourette's syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry 1996; 57 (Suppl 9): 24–34.

Wolraich ML, Wibbelsman CJ, Brown TE, Evans SW, Gotlieb EM, Knight JR et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adolescents: a review of the diagnosis, treatment, and clinical implications. Pediatrics 2005; 115: 1734–1746.

Rogers SW, Gregori NZ, Carlson N, Gahring LC, Noble M . Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor expression by O2A/oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. Glia 2001; 33: 306–313.

Stocker S, Guttinger HR, Herth G . Exogenous testosterone differentially affects myelination and neurone soma sizes in the brain of canaries. Neuroreport 1994; 5: 1449–1452.

Wang Y, Adamson C, Yuan W, Altaye M, Rajagopal A, Byars AW et al. Sex differences in white matter development during adolescence: a DTI study. Brain Res 2012; 1478: 1–15.

Meyer DC, Carr LA . The effects of perinatal exposure to nicotine on plasma LH levels in prepubertal rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol 1987; 9: 95–98.

Fried PA, James DS, Watkinson B . Growth and pubertal milestones during adolescence in offspring prenatally exposed to cigarettes and marihuana. Neurotoxicol Teratol 2001; 23: 431–436.

Colello RJ, Pott U . Signals that initiate myelination in the developing mammalian nervous system. Mol Neurobiol 1997; 15: 83–100.

Todorich B, Pasquini JM, Garcia CI, Paez PM, Connor JR . Oligodendrocytes and myelination: the role of iron. Glia 2009; 57: 467–478.

de Arriba Zerpa GA, Saleh MC, Fernandez PM, Guillou F, Espinosa de los Monteros A, de Vellis J et al. Alternative splicing prevents transferrin secretion during differentiation of a human oligodendrocyte cell line. J Neurosci Res 2000; 61: 388–395.

Acknowledgements

This project was in part supported by NIH grants DA-013783 and DA-026356 to MDL. We thank Dr. David L Bronson for his excellent editing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest on this work.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Translational Psychiatry website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, J., Wang, J., Dwyer, J. et al. Gestational nicotine exposure modifies myelin gene expression in the brains of adolescent rats with sex differences. Transl Psychiatry 3, e247 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2013.21

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2013.21

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Sex-specific nicotine sensitization and imprinting of self-administration in rats inform GWAS findings on human addiction phenotypes

Neuropsychopharmacology (2021)

-

LINGO-1 siRNA nanoparticles promote central remyelination in ethidium bromide-induced demyelination in rats

Journal of Physiology and Biochemistry (2019)

-

Prenatal Nicotine Exposure Impairs the Proliferation of Neuronal Progenitors, Leading to Fewer Glutamatergic Neurons in the Medial Prefrontal Cortex

Neuropsychopharmacology (2016)

-

Extended access nicotine self-administration with periodic deprivation increases immature neurons in the hippocampus

Psychopharmacology (2015)

-

Environmental tobacco smoke in the early postnatal period induces impairment in brain myelination

Archives of Toxicology (2015)