Abstract

Behavioral isolation in animals can be mediated by inherent mating preferences and assortative traits, such as divergence in the diel timing of mating activity. Although divergence in the diel mating time could, in principle, promote the reproductive isolation of sympatric, conspecific populations, there is currently no unequivocal evidence of this. We conducted different mate-choice experiments to investigate the contribution of differences in diel mating activity to the reproductive isolation of the rice and water-oat populations of Chilo suppressalis. The results show that inter-population difference in diel mating activity contributes to assortative mating in these populations. In the rice population, most mating activity occurred during the first half of the scotophase, whereas in the water-oat population virtually all mating activity was confined to the second half of the scotophase. However, when the photoperiod of individuals from the water-oat population was altered to more closely align their mating activity with that of the rice population, mate choice was random. We conclude that inter-population differences in diel mating time contribute to assortative mating, and thereby the partial reproductive isolation, of these host-associated populations of C. suppressalis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Reproductive isolation in animals often evolves due to geographic barriers, habitat differences, or behavioral isolation, and can ultimately lead to speciation1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Assortative mating is a form of behavioral reproductive isolation that can reduce, or prevent, mating between individuals from different populations8,9,10. Assortative mating is defined as individuals preferentially choosing mates with a similar phenotype to themselves more often than would be expected under a null hypothesis of random mating8. Assortment traits are phenotypic traits such as mating sites11, the timing of mating activity12,13, body size14, body color15 and pheromones16, that influence the likelihood of mating between two individuals17. The mechanisms through which such traits contribute to assortative mating have been extensively documented in many animals9.

The timing of mating often has a diel rhythm, especially in insects12,18,19. Although it has been suggested that differences in diel mating time can potentially induce allochronic reproductive isolation between laboratory-bred strains of the same species12, closely related species20, and host-associated populations21,22, the evidence for this has so far been relatively equivocal. For example, although the rice and corn strains of Spodoptera frugiperda have different diel mating times, this is not the main reason for the reproductive isolation observed between these two strains in the wild23,24. There is still no evidence that divergence in diel mating time is a significant factor in the reproductive isolation of sympatric, conspecific populations.

Chilo suppressalis Walker (Lepidoptera: Crambidae), is an ideal species in which to investigate whether divergence in diel mating time contributes to reproductive isolation between host populations22,25. C. suppressalis is an economically significant pest of gramineous plants, especially rice and water-oats, in the East Asian region22,26,27. In this region rice and water-oats are usually cultivated in neighbouring fields, or planted in rotation in the same fields28,29 and are the only host plants on which C. suppressalis can complete its entire life-cycle without changing host30. Larvae, pupae, and adults, of C. suppressalis fed on rice plants, or collected from rice fields, are smaller than those fed on water-oat plants or collected from water-oat fields25,26,28,31,32. The seasonal peaks of emergence the rice population also differ from those of the water-oat population26,28,29. Furthermore, diel mating activity begins earlier in the rice population than in the water-oat population22,33,34,35. These differences suggest that the rice and water-oat populations of C. suppressalis are sympatric host-races25,29,31,35. Indeed, it has been suggested that differences in seasonal emergence and diel mating activity could be important factors contributing to the development and maintenance of reproductive isolation in these two host-associated populations of C. suppressalis22,25,35. However, because these populations have considerable overlap in the seasonal timing of adult emergence29,35, a slight overlap in the diel timing of mating activity22,34,35, and adults can migrate from rice to water oat fields, and vice versa35, there is potential for hybridization. Indeed, viable hybrid offspring have been produced under laboratory conditions22 and may exist in the wild34. Therefore, both the degree of assortative mating between these two host populations, and the importance of inter-population differences in diel mating time to this, remain unclear.

In this study, different mate choice experiments were designed with two different objectives. These were: (1) to confirm the degree of host-independent, behavioral, partial premating reproductive isolation (mating patterns) between the two host populations suggested by previous studies22,25,35, (2) to determine to what extent divergence in diel mating time contributes to the observed assortative mating of each population. To investigate the mating patterns of the two populations we conducted three kinds of mate choice tests; no choice, single choice (both female and male choice), and multiple choice, throughout the entire scotophase. To determine the contribution of inter-population differences in diel mating time to the mating patterns observed during the above experiments, we manipulated the photoperiod of individuals from the water-oat population to more closely align their peak period of mating activity with that of the rice population, and conducted mate choice experiments during the part of the scotophase in which there was the most overlap in mating activity between the two populations. To further clarify the contribution of inter-population differences in diel mating time to mating patterns, we confined some mate choice tests to the part of the scotophase that included the peak period of mating activity of the water-oat population, which was after the peak of mating activity of the rice population. The results show that these host-populations of C. suppressalis display a considerable degree of assortative mating and that inter-population differences in the diel timing of mating activity contributes to the premating isolation of these populations. This suggests that divergence in diel mating time can both maintain and reinforce the reproductive isolation of animal populations.

Materials and Methods

Insect populations

We collected > 1000 larvae of C. suppressalis from insect-damaged rice stems in a rice field (113°57′E, 30°29′N) and >800 from insect-damaged water-oat stems in a water-oat field (114°16′E, 30°28′N), in Wuhan, China in August 2014. Larvae were kept in an insectarium (temperature, 28 ± 1 °C; relative humidity, 80 ± 5%; photoperiod, light 15 h and dark 9 h). Rice (R) population larvae and water-oat (W) population larvae were reared on rice stems and water-oat fruit pulp, respectively. The time at which newly emerged adults of each population were first observed mating was recorded based on the methods of Samudra et al.22. A newly emerged male (1-day-old) and a newly emerged female (1-day-old) from the same population were randomly paired together and transferred into a clear plastic cup provided with 10% honey solution on a piece of cotton. The onset of mating was checked and recorded every 30 min throughout the scotophase. There was a significant difference in the diel peak mating activity of each population (Supplementary Fig. S1). This difference was considered to be an intrinsic feature of each host-associated population and to be independent of sampling time and locality22,25,34.

The diel peak of mating activity of the two host-populations of C. suppressalis is not affected by larval diet25. Nevertheless, an additional two complete generations of each population were reared on an artificial diet36 in the same insectarium under the conditions described previously between September and November 2014. The diel peaks of mating activity of the third generations of each population were still significantly different (Supplementary Fig. S1). Pupae from each population were sexed and sorted into four separate enclosures (R-males, R-females, W-males and W-females) and provided with 10% honey solution to prevent mating before experiments began. Newly emerged, 1-day-old adults of the third generation were used in mate choice experiments.

Experimental design

The estimated degree of sexual isolation between sister species of Drosophila was significantly higher when experimental designs incorporated choice compared to those in which there was no choice37. Therefore, we used both choice, and no-choice, tests to determine the degree of premating, reproductive isolation (assortative mating) between the R and W populations of C. suppressalis. Tests were conducted by placing pairs, trios, or quartets, in a plastic cup before the beginning of the scotophase and observing their mating activity throughout the scotophase (Fig. 1A).

Schematic diagram of mate choice tests conducted on adults of the rice (R) and water-oat (W) populations of C. suppressalis during (A) the entire scotophase, (B) after the photoperiod of W individuals had been manipulated to align their peak of mating activity with that of R individuals, (C) during the peak period of mating activity of W individuals in the latter part of the scotophase. See Supplementary Table S1 and Materials and Methods for details.

When the results of these tests indicated that mating was nonrandom, we conducted further experiments to determine whether inter-population differences in diel mating time contributed to the observed mating preferences of each population. Previous experiments had shown that virtually all mating activity in the W population was confined to the last 6–7 h of the scotophase. Although the peak of mating activity in the R population occurs in the first half (3–4 h) of the scotophase, some mating activity also occurs in the second half25. Therefore, to test the contribution of differences in diel mating time to intra-population mating patterns, we also conducted additional mate choice tests after synchronizing the mating activity of each population.

We did this in two ways. The first was by altering the photoperiod of some W adults so that their scotophase began 3 h earlier than those reared under the original photoperiod. We did this by rearing part of the third generation W population in another insectarium at the same temperature and humidity as the original insectarium, but, following the method described by Miyatake et al.12 and Schöfl et al.23, under a photoperiod in which the scotophase began 3 h earlier. Although the peak of mating activity in these photoperiod-altered W adults still took place during the last 6–7 h of the scotophase, there was greater overlap between their period of mating activity and that of R population adults than between ordinary W population adults and R population adults. Individuals were placed in the cups after the beginning of the scotophase and their mating activity observed during the final six hours of the scotophase (Fig. 1B).

The second method was, following Schöfl et al.23, to confine single choice tests to the latter part of the scotophase. We did this by placing chooser individuals into cups before the beginning of the scotophase, introducing their prospective mates 5 h into the scotophase and recording the start time of copulation throughout the remainder of the scotophase (Fig. 1C).

Observation of the mating behavior in different choice tests

No choice tests

A virgin female and a virgin male were randomly paired together in a clear plastic cup and provided with 10% honey solution on a piece of cotton (Fig. 1A,B). Four different pair combinations (R♀ × R♂, W♀ × W♂, R♀ × W♂ and W♀ × R♂) were tested. Each pair was checked for copulation every 30 min over the duration of a single, given scotophase. The time at which copulation of each pair combination was first observed was recorded.

Single choice tests

A virgin female, or male, was placed in a clear plastic cup with two virgins of the opposite sex, one from the same, and one from the other, population, and provided with 10% honey solution on a piece of cotton (Fig. 1). Two female-choice experiments, R♀ × R♂ × W♂ and W♀ × R♂ × W♂, and two male-choice experiments, R♂ × W♀ × R♀ and W♂ × W♀ × R♀, were conducted. Males and females could be distinguished by their sexually dimorphic wing patterns. Individuals from each population were marked to distinguish them based on the methods described by Bailey et al.38. We did this by marking the tergum of individual moths with a black dot (Supplementary Fig. S2). To prevent bias, we alternately marked W and R individuals in successive choice tests. Marking did not significantly affect female (R population: χ2 = 0.02, P = 0.88; W population: χ2 = 0.07, P = 0.80) or male (R population: χ2 = 1.72, P = 0.19; W population: χ2 = 0.47, P = 0.49) mate choice. Copulations were scored at 30-min intervals. The population of copulating individuals, and the time at which copulation occurred, were recorded every 30 minutes. When multiple copulations occurred (5 cases in 420 choice trials), only the population and time of copulation of the first pair to copulate were recorded38.

Multiple choice tests

A virgin female and male from each population (R♀ × R♂ × W♀ × W♂) (Fig. 1A), were placed in a clear plastic cup, so that each had a choice of two potential mates. Individuals from each population were identified by marking as described above. The population, and sex, of the first pair to mate in each trial was recorded38.

All females and males used in experiments were 1 day old. All experiments were conducted over ten consecutive scotophases. About 180–320 choice trials were conducted in each scotophase depending on the numbers of adults that had emerged. Different choice experiments were randomized across the ten scotophases.

Data analysis

The mating patterns and degree of sexual isolation between the W and R populations in different choice tests were estimated by the pair total index (PTI) and joint isolation index (IPSI)37,39. The PTI estimates whether the mating pattern of each pairing is different from random mating. PTI values significantly different from 1 indicate assortative mating between two populations. Mating patterns between two populations are considered assortative when IPSI values are significantly different from 0. Although the contribution of differences in diel mating time is confounded by mate preference, IPSI was also calculated for male-choice and female-choice tests to compare the degrees of sexual isolation estimated by different choice tests. A similar method of data analysis was used in previous studies37,39. The PTI and IPSI were calculated using the JMATING software package40. The built-in statistical analysis program in this software estimated the significance of PTI and IPSI by resampling 10,000 times and providing average PTI and IPSI values37,41. Following Schöfl et al.23, we used a G–test to test whether the proportions of the four potential mating combinations were significantly different.

Female and males from each population may have contributed differently to the observed mating patterns. Therefore, following Korol et al. and Schöfl et al.23,42, a maximum-likelihood modeling approach was adopted to evaluate the respective contributions of divergence in the diel timing of mating activity and mate preference.

In brief, the model assumes that the probability of mating between a female and a male individual in single choice test is determined by (1) the female’s and male’s motivation to mate during the observation period, (2) the female’s or male’s degree of preference for individuals from same population versus those from another population. Eight parameters  could be independently quantified by the number of intra- and inter-population copulations observed in single choice tests. The parameters

could be independently quantified by the number of intra- and inter-population copulations observed in single choice tests. The parameters  and

and  represent the mating activity of males and females of the R and W populations, respectively, and

represent the mating activity of males and females of the R and W populations, respectively, and  represent the respective mating preference of males and females of these populations. The relative contribution of divergence in diel timing of mating activity and mating preferences can be effectively controlled and partitioned by the model. Some preconditions and assumptions are necessary for the model to be valid23,42 (for more details see Supplementary Methods).

represent the respective mating preference of males and females of these populations. The relative contribution of divergence in diel timing of mating activity and mating preferences can be effectively controlled and partitioned by the model. Some preconditions and assumptions are necessary for the model to be valid23,42 (for more details see Supplementary Methods).

Based on the numbers of each mating combination and unpaired individuals, we estimated a vector with the eight parameters by maximizing a likelihood function (see Supplementary Methods). This was accomplished by numerical optimization executed using the mle2 function in the R package bbmle. To evaluate the relative contributions of divergence in diel mating activity and mating preference, different constraints were used on the parameters (e.g. no difference in mating activity between the sexes of both populations,  ). The likelihoods of models with different constraints could then be compared via likelihood ratio tests (LRTs)23,42 (See Supplementary Methods for details). This approach allowed us to infer the relative contributions of divergence in diel mating activity and mating preferences to the observed mating patterns. All analyses were performed in R-3.2.2 statistical software43.

). The likelihoods of models with different constraints could then be compared via likelihood ratio tests (LRTs)23,42 (See Supplementary Methods for details). This approach allowed us to infer the relative contributions of divergence in diel mating activity and mating preferences to the observed mating patterns. All analyses were performed in R-3.2.2 statistical software43.

Results

Results of mate choice tests conducted over the entire scotophase

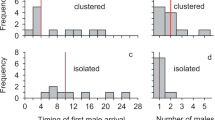

In no choice tests, the timing of the onset of copulation varied depending on whether the potential mate was from the same population or not (Fig. 2A,B). Copulation between R females and R males mostly occurred 3–4 h into the scotophase, but copulation between R females and W males mostly occurred 6–7 h into scotophase (Fig. 2A). Copulation involving W females mostly occurred 6–7 h into the scotophase, irrespective of the type of male present (Fig. 2B). The frequency of mating between homotypic pairs (R♀ × R♂, 76/150, 50.7%, W♀ × W♂, 94/150, 62.7%) was significantly higher than that between heterotypic pairs (R♀ × W♂, 33/150, 22.0%; W♀ × R♂, 45/150, 30.0%) (G-test of independence: G = 66.1, P < 0.001). PTI values were significantly > 1 for homotypic pairs but significantly < 1 for heterotypic pairs (Table 1). The overall IPSI value was 0.38 ± 0.06 (P < 0.001). These results indicate that individuals preferred to mate with those from the same population even when they were not given a choice of mate.

(A) no choice (R♀ × R♂ and R♀ × W♂); (B) no choice (W♀ × R♂ and W♀ × W♂); (C) female choice (R♀ × R♂ and R♀ × W♂); (D) female choice (W♀ × R♂ and W♀ × W♂); (E) male choice (R♀ × R♂ and R♀ × W♂); (F) male choice (W♀ × R♂ and W♀ × W♂); (G) multiple choice (R♀ × R♂ and R♀ × W♂); (H) multiple choice (W♀ × R♂ and W♀ × W♂). Sample sizes and proportion of different mating combinations shown in parentheses. The first value is the number of mating pairs and the second is the number of potential pairs; the percentage is the proportion of each specified pairing. See Supplementary Table S1 for details of sample sizes.

In female-choice experiments (Fig. 2C,D), R females mated with R males (R♀ × R♂, 37/100, 37.0%) more frequently than with W males (R♀ × W♂, 11/100, 11.0%) (Supplementary Table S1). R females generally mated with R males in the first half of the scotophase, but generally mated with W males during the second half scotophase (Fig. 2C,D). W females also preferred to mate with W males (W♀ × W♂, 39/100, 39.0%), but did not reject R males (W♀ × R♂, 24/100, 24.0%) (Supplementary Table S1). The PTI value for R♀ × W♂ copulation was significantly < 1 (Table 2) whereas the PTI value for W♀ × W♂ copulation was significantly > 1 (Table 2) and overall IPSI was 0.40 ± 0.09 (P < 0.001). This indicates that, when given a choice, females preferred to mate with a male from the same population.

In male-choice experiments (Fig. 2E,F), R males mated more often with R females (R♀ × R♂, 34/100, 34.0%) than with W females (W♀ × R♂, 17/100, 17.0%) (Supplementary Table S1), but W males mated almost as often with R females as with W females (W♀ × W♂, 32/100, 32.0%; R♀ × W♂, 27/100, 27.0%) (Supplementary Table S1). R males generally mated with R females (Fig. 2E) during the first half of the scotophase whereas copulation between all other potential combinations of mating pairs (W♂ × R♀, R♂ × W♀, W♂ × W♀) generally occurred later in the scotophase (Fig. 2E,F). The PTI value for W♂ × R♀ and W♂ × W♀ mating were neither significantly < 1 nor > 1 and the overall IPSI value was 0.21 ± 0.09 (P = 0.02). These results indicate that, when given a choice of mate, males displayed a relatively weak preference for females from the same population.

In multiple choice experiments (Fig. 2G,H), copulation between homotypic pairs (R♀ × R♂, 38/150, 25.3% and W♀ × W♂, 48/150, 32%) was more common than between heterotypic pairs (R♀ × W♂ 13/150, 8.7% and W♀ × R♂ 20/150, 13.3%) (Supplementary Table S1). The peak of copulation between R females and R males occurred 3–4 h into the scotophase (Fig. 2G), whereas copulation between all other potential combinations of mating pairs (R♀ × W♂, W♀ × R♂, W♀ × W♂) took place 6–7 h into scotophase (Fig. 2G,H). PTI values for R♀ × W♂ and W♀ × R♂ mating pairs were significantly < 1, whereas the PTI value for W♀ × W♂ pairs was significantly > 1 (Table 2). The overall IPSI value was 0.45 ± 0.08 (P < 0.001). These results indicate that assortative mating occurred when multiple males or females from each population were present in the same enclosure.

The onset of mating between R females and R males always occurred in the first half the scotophase, whereas almost all copulation involving W males or females took place in the second half of the scotophase (Fig. 2). These results suggest that these inter-population differences in diel mating time play an important role in assortative mating by R and W individuals.

Results of mate choice tests conducted after synchronizing the mating activity of individuals from each population

To determine the degree to which the inter-population differences in diel mating activity contribute to the observed mating patterns of the two populations, mate choice experiments were repeated after the photoperiod of W individuals had manipulated to more closely synchronize their mating activity with those from the R population.

Under these conditions PTI values for all potential pairings in no choice experiments were not significantly different from 1 (Table 2) and the overall IPSI was 0.03 ± 0.07 (P = 0.636), indicating no significant departure from the null hypothesis of random mating. IPSI values obtained from single female and male choice experiments were 0.11 ± 0.11 (P = 0.311) and IPSI = 0.07 ± 0.10, P = 0.486), respectively, which are also consistent with random mate choice. Mating was also random in multiple choice experiments (IPSI = 0.07 ± 0.10, P = 0.499). These results suggest that inter-population differences in diel mating time are a major factor contributing to the assortative mating of the R and W populations of C. suppressalis.

The relative contribution of individual mate preferences and inter-population differences in diel mating activity to assortative mating in each population

In order to estimate the relative contributions of the inter-population differences in diel mating activity and individual mating preferences to assortative mating in each population, we obtained different mating parameters from a maximum-likelihood model of single mate choice during different parts of the scotophase, and after synchronizing the mating activity of adults from both populations (Table 3).

When individuals were able to exercise mate choice throughout the scotophase, the mating activity between male and female individuals from the same population was not significantly different (Table 3: rice population, MA1 vs. MA0, χ2 = 0.00, P = 0.99; water-oat population MA2 vs. MA1, χ2 = 0.30, P = 0.59). The mating activity between individuals from the different populations was, however, significantly different (Table 3: MA3 vs. MA2, χ2 = 5.57, P = 0.02). Although females and males of the W population mated at random in single mate choice experiments (Table 3: male, MA4 vs. MA2, χ2 = 0.00, P = 0.98; female, MA5 vs. MA4, χ2 = 1.55, P = 0.21), males and females of the R population had a significant preference for mates from the same population (Table 3: male, MA6 vs. MA5, χ2 = 8.97, P = 0.003; female, MA7 vs. MA5, χ2 = 19.76, P < 0.001).

When single choice tests were conducted after the photoperiod of W adults had been altered to synchronize their mating activity with that of R adults, the mating activity between individuals from the different populations was still significantly different (Table 3: MB3 vs. MB2, χ2 = 5.21, P = 0.02). However, females and males no longer had significant mating preferences (Table 3: MB4 vs. MB2, χ2 = 2.10, P = 0.14; MB5 vs. MB4, χ2 = 1.68, P = 0.19; MB6 vs. MB5 χ2 = 0.02, P = 0.90; MB7 vs. MB6, χ2 = 0.05, P = 0.86).

When mate choice was confined to the latter part of the scotophase, the mating activity within each population was not significantly different (Table 3: R population, MC1 vs. MC0, χ2 = 0.00, P = 0.99; W population MC2 vs. MC1, χ2 = 0.29, P = 0.59), but the mating activity between individuals from different populations was still significantly different (Table 3: MC3 vs. MC2, χ2 = 8.82, P = 0.003). R females and males now chose mates randomly (Table 3: male, MC4 vs. MC2, χ2 = 0.16, P = 0.90; female, MC5 vs. MC4, χ2 = 2.61, P = 0.11) but W males still significantly preferred females from the same population (Table 3: MC6 vs. MC5, χ2 = 6.10, P = 0.01). W females also preferred males from the same population, but this preference was not statistically significant (Table 3: MC7 vs. MC5, χ2 = 3.34, P = 0.06).

In summary, the diel timing of mating activity significantly differed between individuals from the R and W populations irrespective of which part of the scotophase choice experiments were conducted (Table 3). Individuals from R populations displayed significant mating preferences when mate choice experiments were conducted throughout the entire scotophase, but did not when experiments were confined to the latter part of the scotophase (Table 3). However, individuals from W populations displayed obvious mating preferences when experiments were confined to the latter part of the scotophase, but did not when experiments were conducted throughout the entire scotophase (Table 3). Individuals from both populations did not display significant mating preferences when the photoperiod of W adults had been altered to more closely synchronize their mating activity with that of R adults (Table 3).

Discussion

Assortative mating is an important mechanism that establishes and maintains reproductive isolation between animal populations4,8. Assortative mating has two main components; mate choice and assortment traits8. Assortment traits are phenotypes which are expressed in both males and females that enhance the preference of individuals for mates with similar traits8. The importance of assortment traits, including mating site preferences, timing of seasonal emergence, and body size, in assortative mating has been well documented11. However, it remains unclear whether inter-population differences in diel mating time can produce a degree of assortative mating to contribute to the reproductive isolation of animal populations. The results of this study show that R and W populations of C. suppressalis display a significant degree of assortative mating, and that this is mainly due to inter-population differences in diel mating time.

The mating behavior of many insects has a diel rhythm which is controlled by an endogenous circadian clock18. In general, diel rhythms of mating activity are species-specific, and could play a key role in maintaining the reproductive isolation of closely related species18,19. For example, it has been suggested that allochronic variation in mating activity is a key factor in the reproductive isolation of sympatric strains of the fall armyworm S. frugiperda21,44. However, to date, the evidence for this has been equivocal. Indeed, behavioral experiments indicate that female mate preferences contribute more to the reproductive isolation of strains of this species than allochronic variation in mating activity23.

It has also been suggested that differences in diel mating activity could be an important factor maintaining the reproductive isolation of the R and W populations of C. suppressalis22,25,35. In the present study, IPSI values ranged from 0.21 to 0.45, indicative of partial reproductive isolation, when individuals from each population were allowed to exercise mate choice throughout the entire scotophase. However, after the photoperiod of individuals from the W population was altered to more closely synchronize their mating activity with those of the R population, the estimated degree of reproductive isolation fell to almost zero. These results indicate that, in contrast to results obtained by Schöfl et al. on S. frugiperda23, inter-population differences in diel mating time make an important contribution to the reproductive isolation of these host-associated populations of C. suppressalis.

The results of this study show that different mate choice tests (e.g. female vs male choice) give different IPSI values and similar variation has been reported in previous studies23,37,39. This is consistent with the hypothesis that the degree of reproductive isolation varies under different mating systems, and therefore, experimental designs37,45. Therefore, determining the degree of reproductive isolation between host-populations of C. suppressalis requires clarification of the mating system of this species. In moths in general, the mating process has two successive stages. In the first, female moths release sex pheromones that are used by males to locate them46. The initial mate choice is therefore made by males. Although it has been reported that the quantity of sex pheromones produced by females of the R and W populations differ47, field studies show that female sex pheromones of either population are equally effective at luring males of either population into traps35. For this reason we did not include a long-range, male-choice experiment in this study. In the second stage of the mating process, one, or more, males encounter a female, or females, which then choose a male to mate with48,49. During this stage, sex pheromones emitted by males may influence female choice and female sex pheromones may also continue to influence male choice. Thus, both males and females can potentially exercise mate choice during this, close proximity, stage of the mating process. In our study, the strength of male and female mate choice is likely to differ, which could explain the different IPSI values obtained from our male choice (0.21), and female choice (0.40), experiments. The difference in these values is an estimation of the contribution of female, or male, mate choice to the partial reproductive isolation of these two populations. To explore the relative strengths of female and male choice in the second stage of the mating process, more detailed information on the courtship behavior of males and females is required, especially on the timing of pheromone emission23,37. Nonetheless, our results demonstrate that inter-population differences in the diel mating time of the R and W populations of C. suppressalis make a significant contribution to the partial reproductive isolation of these populations.

Traditional estimators of sexual isolation often confound inter-population differences in mating activity with individual mate choice23,41,50. For example, in the fall armyworm, there is a difference in the mating activity of the corn and rice strains of this species during the latter part of the scotophase, but not over the entire scotophase23. However, female preference to homotypic males in this species is due more to female mate choice than this difference in diel mating activity23. Although we didn’t observe courtship behavior in detail, which may have allowed us to separate the effects of inter-population differences in mating activity from mate choice23,37, the relative effect of these factors on mate choice can be effectively separated with a modeling approach23,42. We found differences in the mating activity of the R and W populations of C. suppressalis irrespective of which part of the scotophase was monitored. Moreover, the overall mating activity of the W population was higher than that of the R population during a specific part of the scotophase, which may explain the higher mating frequency of homotypic pairs of this population in no choice tests. We observed assortative mating in the R population when single choice tests were conducted throughout the entire scotophase, and assortative mating in the W population when tests were confined to the later part of the scotophase. However, there was no evidence of assortative mating by either population when mate choice tests were confined to the part of the later part of scotophase when the mating activity of both populations overlapped. These results suggest that the apparent preference to mate with individuals from the same population is actually due to inter-population differences in diel mating time. In other words, males or females will mate with any sexually active individual they encounter in the later portion the scotophase. This indicates an asymmetry of reproductive isolation between the two populations. Similar asymmetry in patterns of premating isolation has been reported in many insects15,23,42,51,52 and in fish53. In the R population, mating activity occurred throughout the entire scotophase but was more frequent in the first half of the scotophase, whereas in the W population almost all mating activity was confined to the second half of the scotophase. Copulation between heterotypic pairs was therefore almost always confined the second half of the scotophase, simply because individuals of the W population were rarely sexually active in the first half. Further research is required to investigate why the diel timing of mating activity is more variable in the rice population than in the water-oat population. In addition, because presence of leaves of water-oat plants promote mating by individuals from both populations22, it would be interesting to clarify whether the lower mating activity of the rice population is a fitness cost incurred by long-term adaption to rice.

In conclusion, our results suggest that inter-population differences in diel mating time make a significant contribution to the reproductive isolation of the R and W populations of C suppressalis. It should be noted, however, that viable hybrids are readily produced under laboratory conditions22 and evidence of asymmetric mating between the two populations was found in the present study. This suggests that the observed difference in diel mating time is unlikely to be the sole factor maintaining the partial reproductive isolation of these two populations in the wild. Indeed, the establishment and maintenance of the reproductive isolation of populations often requires the simultaneous, or successive, action of both pre- and post-mating isolation mechanisms54,55,56,57, for example, in some animals, body size can affect mating patterns9. Although high variation in body size within both populations has been reported in C. suppressalis28,31,58, there are also a significant inter-population differences in body size25,26,28,31,32. Therefore, to comprehensively evaluate the contribution of inter-population differences in diel mating time to the reproductive isolation of the R and W populations of C. suppressalis will require the investigation of other potential barriers to gene flow between these populations, such as size-assortative mating, seasonal allochronic isolation and habitat isolation. In addition, it would be interesting to investigate the ecological factors responsible for the divergence in diel mating times in these two populations. We speculate that diel mating time may be related to the timing of the release of host plant volatiles59. These are known to have a stimulatory effect on pheromone production and promote mating in insects60, but more work is needed to clarify their effect on C. suppressalis.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Quan, W.-L. et al. Difference in diel mating time contributes to assortative mating between host plant-associated populations of Chilo suppressalis. Sci. Rep. 7, 45265; doi: 10.1038/srep45265 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Dobzhansky, T. Genetics and the origin of species (Columbia University Press, 1937).

Mayr, E. Animal species and evolution (Belknap Press, 1963).

Diehl, S. & Bush, G. An evolutionary and applied perspective of insect biotypes. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 29, 471–504 (1984).

Dres, M. & Mallet, J. Host races in plant-feeding insects and their importance in sympatric speciation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 357, 471–492 (2002).

Coyne, J. A. & Orr, H. A. Speciation (Sinauer Associates Sunderland, 2004).

Dieckmann, U. Adaptive speciation (Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Berlocher, S. H. & Feder, J. L. Sympatric speciation in phytophagous insects: Moving beyond controversy? Annu. Rev. Entomol. 47, 773–815 (2002).

Bolnick, D. I. & Fitzpatrick, B. M. Sympatric speciation: models and empirical evidence. Annu. Rev. Eco. Evol. S. 38, 459–487 (2007).

Jiang, Y., Bolnick, D. I. & Kirkpatrick, M. Assortative mating in animals. Am. Nat. 181, E125–E138 (2013).

Mullen, S. P. & Shaw, K. L. Insect speciation rules: Unifying concepts in speciation research. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 59, 339–361 (2014).

Ohshima, I. Host-associated pre-mating reproductive isolation between host races of Acrocercops transecta: mating site preferences and effect of host presence on mating. Ecol. Entomol. 35, 253–257 (2010).

Miyatake, T. et al. The period gene and allochronic reproductive isolation in Bactrocera cucurbitae . P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci 269, 2467–2472 (2002).

Eubanks, M. D., Blair, C. P. & Abrahamson, W. G. One host shift leads to another? Evidence of host-race formation in a predaceous gall-boring beetle. Evolution 57, 168–172 (2003).

Arnqvist, G., Rowe, L., Krupa, J. J. & Sih, A. Assortative mating by size: A meta-analysis of mating patterns in water striders. Evol. Ecol. 10, 265–284 (1996).

Boughman, J. W., Rundle, H. D. & Schluter, D. Parallel evolution of sexual isolation in sticklebacks. Evolution 59, 361–373 (2005).

Pélozuelo, L., Meusnier, S., Audiot, P., Bourguet, D. & Ponsard, S. Assortative mating between European corn borer pheromone races: beyond assortative meeting. PLoS ONE 2, e555, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000555 (2007).

Dieckmann, U. & Doebeli, M. On the origin of species by sympatric speciation. Nature 400, 354–357 (1999).

Sakai, T. & Ishida, N. Circadian rhythms of female mating activity governed by clock genes in Drosophila . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 9221–9225 (2001).

Groot, A. T. Circadian rhythms of sexual activities in moths: a review. Fron. Ecol. Evol. 2, 43, doi: 10.3389/fevo.2014.00043 (2014).

An, X. et al. The period gene in two species of tephritid fruit fly differentiated by mating behaviour. Insect Mol. Biol. 11, 419–430 (2002).

Pashley, D. P., Hammond, A. M. & Hardy, T. N. Reproductive isolating mechanisms in fall armyworm host strains (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 85, 400–405 (1992).

Samudra, I. M., Emura, K., Hoshizaki, S., Ishikawa, Y. & Tatsuki, S. Temporal differences in mating behavior between rice- and water-oats-populations of the striped stem borer, Chilo suppressalis (Walker) (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool. 37, 257–262 (2002).

Schöfl, G., Dill, A., Heckel, D. G. & Groot, A. T. Allochronic separation versus mate choice: nonrandom patterns of mating between fall armyworm host strains. Am. Nat. 177, 470–485 (2011).

Saldamando-Benjumea, C. I., Estrada-Piedrahíta, K., Velásquez-Vélez, M. I. & Bailey, R. I. Assortative mating and lack of temporality between corn and rice strains of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae) from Central Colombia. J. Insect Behav. 27, 555–566 (2014).

Quan, W.-L. et al. Do differences in life-history traits and the timing of peak mating activity between host-associated populations of Chilo suppressalis have a genetic basis? Ecol. Evol. 6, 4478–4487 (2016).

Maki, Y. & Yamashita, M. Ecological difference of rice stem borer, Chilo suppressalis Walker in the various host plants. Bull. Hyogo. Pref. Agric. Exp. Stn. 3, 47–50 (1956).

Hou, M. L., Lin, W. & Han, Y. Q. Seasonal changes in supercooling points and glycerol content in overwintering larvae of the Asiatic rice borer from rice and water-oat plants. Environ. Entomol. 38, 1182–1188 (2009).

Tsuchida, K. & Ichihashi, H. Estimation of monitoring range of sex pheromone trap for the rice stem borer moth, Chilo suppressalis (Walker) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) by male head width variation in relation to two host plants, rice and water oats. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 30, 407–414 (1995).

Matsukura, K., Hoshizaki, S., Ishikawa, Y. & Tatsuki, S. Differences in timing of the emergence of the overwintering generation between rice and water-oats populations of the striped stem borer moth, Chilo suppressalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool. 44, 485–489 (2009).

Jiang, W. H. et al. Study on host plants for reproduction of Chilo suppressalis . J. Asia Pac. Entomol. 18, 591–595 (2015).

Matsukura, K., Hoshizaki, S., Ishikawa, Y. & Tatsuki, S. Morphometric differences between rice and water-oats population of the striped stem borer moth, Chilo suppressalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool. 41, 529–535 (2006).

Ding, N. et al. A comparison of the larval overwintering biology of the striped stem borer, Chilo suppressalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae), in rice and water-oat fields. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 48, 147–153 (2013).

Konno, Y. & Tanaka, F. Mating time of the rice-feeding and water-oat-feeding strains of the rice stem borer, Chilo suppressalis (Walker) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Jpn. J. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 40, 245–247 (1996).

Ishiguro, N., Yoshida, K. & Tsuchida, K. Genetic differences between rice and water-oat feeders in the rice stem borer, Chilo suppressalis (Walker) (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Appl. Entomol. Zool. 41, 585–593 (2006).

Ueno, H., Furukawa, S. & Tsuchida, K. Difference in the time of mating activity between host-associated populations of the rice stem borer, Chilo suppressalis (Walker). Entomol. Sci. 9, 255–259 (2006).

Han, L., Li, S., Liu, P., Peng, Y. & Hou, M. New artificial diet for continuous rearing of Chilo suppressalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 105 (2012).

Coyne, J. A., Elwyn, S. & Rolán-Alvarez, E. Impact of experimental design on Drosophila sexual isolation studies: direct effect and comparison to field hybridization data. Evolution 59, 2588–2601 (2005).

Bailey, R., Thomas, C. & Butlin, R. Premating barriers to gene exchange and their implications for the structure of a mosaic hybrid zone between Chorthippus brunneus and C. jacobsi (Orthoptera: Acrididae). J. Evol. Biol. 17, 108–119 (2004).

Xue, H.-J., Li, W.-Z. & Yang, X.-K. Assortative mating between two sympatric closely-related specialists: inferred from molecular phylogenetic analysis and behavioral data. Sci. rep. 4, doi: 10.1038/srep05436 (2014).

Carvajal-Rodriguez, A. & Rolan-Alvarez, E. JMATING: a software for the analysis of sexual selection and sexual isolation effects from mating frequency data. BMC Evol. Biol. 6, 1–5 (2006).

Rolán-Alvarez, E. & Caballero, A. Estimating sexual selection and sexual isolation effects from mating frequencies. Evolution 54, 30–36 (2000).

Korol, A. et al. Nonrandom mating in Drosophila melanogaster laboratory populations derived from closely adjacent ecologically contrasting slopes at “Evolution Canyon”. P. Natl. acad. sci. USA 97, 12637–12642 (2000).

R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, http://www.r-project.org/ (2015).

Schöfl, G., Heckel, D. G. & Groot, A. T. Time-shifted reproductive behaviours among fall armyworm (Noctuidae: Spodoptera frugiperda) host strains: evidence for differing modes of inheritance. J. Evol. Biol. 22, 1447–1459 (2009).

Dougherty, L. R. & Shuker, D. M. The effect of experimental design on the measurement of mate choice: a meta-analysis. Behav. Ecol. 26, 311–319 (2015).

Rutowski, R. L. Mate choice and Lepidopteran mating behavior. Fla. Entomol. 65, 72–82 (1982).

Kiritani, K. & Tatsuki, S. The rice stem borer, Chilo suppressalis: A history of applied entomology in Japan (University of Tokyo Press, 2009).

Phelan, P. L. & Baker, T. C. Evolution of male pheromones in moths: reproductive isolation through sexual selection? Science 235, 205–207 (1987).

Birch, M., Poppy, G. & Baker, T. Scents and eversible scent structures of male moths. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 35, 25–54 (1990).

Gilbert, D. & Starmer, W. Statistics of sexual isolation. Evolution 39, 1380–1383 (1985).

Falk, J. J., Parent, C. E., Agashe, D. & Bolnick, D. I. Drift and selection entwined: asymmetric reproductive isolation in an experimental niche shift. Evol. Ecol. Res. 14, 403–423 (2012).

Evans, G. M. V., Nowlan, T. & Shuker, D. M. Patterns of reproductive isolation within and between two Lygaeus species characterized by sexual conflicts over mating. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 116, 890–901 (2015).

Hurt, C. R., Farzin, M. & Hedrick, P. W. Premating, not postmating, barriers drive genetic dynamics in experimental hybrid populations of the endangered Sonoran topminnow. Genetics 171, 655–662 (2005).

Sobel, J. M. & Chen, G. F. Unification of methods for estimating the strength of reproductive isolation. Evolution 68, 1511–1522 (2014).

Groot, A. T., Marr, M., Heckel, D. G. & Schöfl, G. The roles and interactions of reproductive isolation mechanisms in fall armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) host strains. Ecol. Entomol. 35, 105–118 (2010).

Lowry, D. B., Modliszewski, J. L., Wright, K. M., Wu, C. A. & Willis, J. H. The strength and genetic basis of reproductive isolating barriers in flowering plants. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci 363, 3009–3021 (2008).

Dopman, E. B., Robbins, P. S. & Seaman, A. Components of reproductive isolation between North American pheromone strains of the European corn borer. Evolution 64, 881–902 (2010).

Xu, S. et al. Relationships between body weight of overwintering larvae and supercooling capacity; diapause intensity and post-diapause reproductive potential in Chilo suppressalis Walker. J. Insect Physiol. 57, 653–659 (2011).

Sufang, Z., Jianing, W., Zhen, Z. & Le, K. Rhythms of volatiles release from healthy and insect-damaged Phaseolus vulgaris. Plant Signal. Behav. 8, e25759, doi: 10.4161/psb.25759 (2013).

Reddy, G. V. P. & Guerrero, A. Interactions of insect pheromones and plant semiochemicals. Trends Plant Sci. 9, 253–261 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dan Sun, Yi Li, Shuang Guo and Han-Yu Zhou for their generous help in collecting, and rearing, insects. This study was funded by grants from the Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 2016CFA068), the Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education (Grant number 20130146110027), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant number 2014PY036).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.L.Q., R.Q.Z., W.H.M., C.L.L. and X.P.W. designed the experiments. W.L.Q. R.Q.Z. and R.C. conducted the experiments. W.L.Q., W.L. and X.P.W. analyzed the data. W.L.Q., W.L. and X.P.W. wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Quan, WL., Liu, W., Zhou, RQ. et al. Difference in diel mating time contributes to assortative mating between host plant-associated populations of Chilo suppressalis. Sci Rep 7, 45265 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45265

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45265

This article is cited by

-

Age-related mating rates among ecologically distinct lineages of bedbugs, Cimex lectularius

Frontiers in Zoology (2023)

-

Comparative transcriptomics of the pheromone glands provides new insights into the differentiation of sex pheromone between two host populations of Chilo suppressalis

Scientific Reports (2020)

-

Divergence in larval diapause induction between the rice and water-oat populations of the striped stem borer, Chilo suppressalis (Walker) (Lepidoptera: Crambidae)

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.