Abstract

Ni0.9Fe0.1 alloy-supported solid oxide fuel cells with NiTiO3 (NTO) infiltrated into the cell support from 0 to 4 wt.% are prepared and investigated for CH4 steam reforming activity and electrochemical performance. The infiltrated NiTiO3 is reduced to TiO2-supported Ni particles in H2 at 650 °C. The reforming activity of the Ni0.9Fe0.1-support is increased by the presence of the TiO2-supported Ni particles; 3 wt.% is the optimal value of the added NTO, corresponding to the highest reforming activity, resistance to carbon deposition and electrochemical performance of the cell. Fueled wet CH4 at 100 mL min−1, the cell with 3 wt.% of NTO demonstrates a peak power density of 1.20 W cm−2 and a high limiting current density of 2.83 A cm−2 at 650 °C. It performs steadily for 96 h at 0.4 A cm−2 without the presence of deposited carbon in the Ni0.9Fe0.1-support and functional anode. Five polarization processes are identified by deconvoluting and data-fitting the electrochemical impedance spectra of the cells under the testing conditions; and the addition of TiO2-supported Ni particles into the Ni0.9Fe0.1-support reduces the polarization resistance of the processes ascribed to CH4 steam reforming and gas diffusion in the Ni0.9Fe0.1-support and functional anode.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

On-cell methane (CH4) reforming in Ni-based anodes is an attractive option for directly using CH4-based fuels for solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) with high fuel efficiency and simplified system design1,2. CH4 steam reforming is a catalytic process for commercial production of H2 or syngas at a H2:CO molar ratio of 3:1 according to the endothermic reaction of

Excessive addition of H2O will further converts CO to CO2 by the slightly exothermic water gas shift (WGS) reaction3,4,5.

If these reactions are taking place in the anode of an SOFC, H2 is consumed via electrochemical oxidation to generate electrical power6,7, forming by-product of H2O. Such in-situ formed H2O is simultaneously used for CH4 steam reforming, which reduces the amount of externally added H2O to improve the electrical efficiency of the SOFC system.

However, for on-cell CH4 reforming in Ni-based anodes, coking is frequently observed in the anode when steam/carbon (H2O/CH4) ratio is low, since Ni catalyzes CH4 decomposition that produces deposited carbon in the form of filament or particle via either CH4 cracking or the Boudouard reactions as follow

The soot-like carbon particles are distributed on the surface of Ni particles, occupying the active sites for electrochemical reaction and the pores for fuel gas transport8; and the carbon filaments formed by carbon diffusion into/precipitation out the Ni particles9 disintegrate the Ni-cermet anode by lifting out the Ni particles from the anode (dusting).

It has been demonstrated that infiltration of oxides, such as rare-earth doped CeO210,11,12, BaO13 and CaO-MgO14, into the Ni-based anode is an effective way to enhance its coking resistance by suppressing carbon formation and promoting steam-carbon reactions. Although TiO2 has not been investigated in SOFCs, it was used as a support in catalysts for steam reforming of hydrocarbons (methanol15, ethanol16 and glycerol17), CO2 reforming of CH415,18 and CO oxidation19; and high coking resistance was demonstrated in CH420 and ethanol16 reforming. Stimulated by these investigations, TiO2 was evaluated in direct-CH4 SOFCs for the enhancement of CH4 on-cell reforming in the present study.

Compared with electrolyte- and electrode-supported SOFCs, metal-supported SOFCs have some advantages in the aspects of electrical/thermal conductivity and mechanical ductility; consequently, the temperature distribution in and tolerance to thermal cycle of the cell are improved21,22. In our previous study, Ni-Fe alloy-supported SOFCs were investigated with the purpose of using wet (3 vol.% H2O) CH4 as the fuel, and high performance (0.6 V at 0.4 A cm−2 and 650 °C for 50 h7) was achieved. However, the Ni0.9Fe0.1-support used was not fully resistant to carbon deposition, and carbon lumps were formed in its large pores. In order to develop metal-supported direct-hydrocarbon SOFCs, Ni0.9Fe0.1-supported SOFCs were prepared with NiTiO3 infiltrated into the Ni0.9Fe0.1-support. It was expected that NiTiO3 would be reduced into TiO2-supported Ni particles in H2 to enhance CH4 reforming activity and resistance to carbon deposition of the Ni0.9Fe0.1-supported cells.

Results

Materials and cell characterization

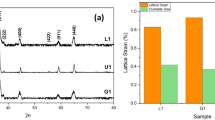

Figure 1a–c show the XRD patterns of the as-synthesized and reduced NTO and co-fired powder mixture of NiO, Fe2O3 and NTO. The as-synthesized NTO demonstrated a perovskite structure of NiTiO3 (JCPDF# 76-0334), and the reduced product was a mixture of TiO2 (JCPDF# 21-1276) and Ni (JCPDF# 04-0850). Figure 1d shows EDS mappings of Ni, Ti and O for the mixture. It indicates that the bright granules in surface are identified by EDS as metallic Ni, and the dark areas rich in Ti and O. Based on this result, it is expected that the infiltrated NTO particles on the surface of the scaffold of the cell support be reduced into TiO2-supported Ni (0) particles. It was confirmed in our previous study7 that the sintered NiO-Fe2O3 cell support is consisted of two phases of NiO and NiFe2O4, and its reduced form is Ni0.9Fe0.1 alloy. With NTO powder added, the co-fired NiO-Fe2O3-NTO mixture contained NiO, NiFe2O4 and NTO (Fig. 1a), which indicates that NTO was chemically compatible with NiO and NiFe2O4 at temperatures up to 1000 °C and would remain as an independent phase in the scaffold of the sintered NiO-NiFe2O4 cell support.

Shown in Fig. 2 is the SEM microstructure of the fractured cross-section of the reduced cell with Ni0.9Fe0.1-support. As observed previously7, the sintered NiO-NiFe2O4 cell support was reduced into a porous scaffold (58%) with a bimodal pore distribution. The average size of the large pores was around 10 μm, which is beneficial for fuel gas transport in the support to the functional anode; and the small pores within the stem of the scaffold give a high specific surface area that is beneficial for CH4 reforming reaction. The Ni-GDC functional anode was approximately 1αm thick and intimately in contact with the fully dense GDC electrolyte (~10 μm) and the porous cell support (~1 mm). The thickness of the BSCF-LSM cathode was averagely 15 μm. Figure 3 respectively present the microstructure of the sintered and reduced cell supports with various amounts of infiltrated NTO from 1 to 4 wt.% of the weight of the half cell (NiO-Fe2O3 anode-support | NiO-GDC anode | GDC electrolyte).

Reforming activity of infiltrated Ni0.9Fe0.1-supports

CH4 reforming in the Ni0.9Fe0.1-support is a chemical process that in situ produces H2, which is electrochemically oxidized on the functional Ni-GDC anode to generate electrical power with byproduct of steam via the reaction of

Thus the reforming activity of the Ni0.9Fe0.1-support is of critical importance for the performance of the cell with on-cell CH4 reforming. Figure 4 shows the CH4 conversion rate and reforming product distribution at 650 °C in the Ni0.9Fe0.1-supports loaded with different amounts of TiO2-supported Ni particles. The initial values of CH4 conversion rate were approximately 50%, 55%, 58%, 61% and 60% for the Ni0.9Fe0.1-supports loaded with 0%, 1%, 2%, 3% and 4 wt.% of NTO (designated as 0NTO, 1NTO, 2NTO, 3NTO and 4NTO), respectively. This indicates that the addition of TiO2-suported Ni particles in the Ni0.9Fe0.1-support promoted its reforming activity with a limit of 3 wt.% NTO, more than which the conversion rate decreased, possibly due to the over-cover of the reforming active sites on the surface of the Ni0.9Fe0.1 scaffold by TiO2 and increased surface area of the small Ni particles for carbon deposition. The CH4 conversion rate of 0NTO, 1NTO, 2NTO and 4NTO decreased obviously with time after approximately 12 h, only which of 3NTO remained relatively stable during the testing period of 24 h. The main reforming products were H2, CO and CO2 (Fig. 4b–d), and their concentrations varied accordingly with the testing time.

Cell performance

The cells with NTO-infiltrated Ni0.9Fe0.1-supports were evaluated at 650 °C with wet CH4 (3 vol.% H2O) as the fuel; Fig. 5 shows their initial I-V-P curves. The open circuit voltage (OCV) of all the cells was around 0.78 V, due to the partial electronic conduction of GDC electrolyte23. The maximum power densities increased from 0.99 to 1.20 W cm−2 as the NTO loading was increased from 0 to 3 wt.%. Further increasing NTO loading to 4 wt.%, it decreased to 1.17 W cm−2. Figure 6 shows the initial impedance spectra of the cells under a current density of 0.4 A cm−2 (Fig. 6a), from which the ohmic (RO) and polarization (RP) resistances were determined, and the corresponding distributions of relaxation time (DRT, Fig. 6b)24,25. The value of RO of each cell was similar, around 0.063 Ω cm−2, and that of RP varied in an opposite direction to the cell voltage and power density. This tendency of cell performance change with the amount of loaded NTO in the Ni0.9Fe0.1-support is consistent with that of the activity for CH4 steam reforming shown above, which suggests that cell performance improvement is due to the increased reforming activity of the Ni0.9Fe0.1-support and the consequent increase in the amount of H2 available for the anode reaction.

The DRT G(τ) was associated with the impedance Z(w) by the following expression:

Where G(τ) is defined as the DRT of impedance Z, τ is relaxation time, Z′ (∞) is the limitation of the real part of Z as angular frequency w approaches infinity. Consequently, impedance could be represented as series connection of infinite number of parallel polarization resistor G(τ)dτ and a capacitor τ/G(τ)dτ. For a more detailed description of DRT method and application were referred26.

After the initial evaluation, all the cells were further tested at 650 °C and a constant current density of 0.4 A cm−2 for up to 96 h; the results are shown in Fig. 7. The improvement on cell performance durability is in consistence with that on CH4 steam reforming activity. The cells with 0NTO, 1NTO, 2NTO and 4NTO Ni0.9Fe0.1-supports performed 67, 78, 90 and 96 h before the sudden drop of the cell voltage; and the cell with 3NTO Ni0.9Fe0.1-support outperformed the others, degrading linearly at a slow rate of 0.5 mV h−1 during the testing period. Post-test examination confirmed that the sudden voltage drop at the end of the test was caused by cell disintegration due to dusting of the Ni0.9Fe0.1-support. The linear voltage decrease, at nearly the same rate for all the cells, may represent the intrinsic cell degradation that needs further understanding for mechanism, whereas the non-linear voltage decrease is attributed to carbon deposition in the Ni0.9Fe0.1-support and functional anode. Since the deposited carbon remained in the cell, its amount can be quantified from the temperature-programmed oxidation (TPO) profile of the post-test cells, as shown in Fig. 8. The area of CO2 peak, an indication of the amount of CO2 formed from deposited carbon, were 7.89 × 10−8, 6.93 × 10−8, 2.61 × 10−8 and 3.15 × 10−8 for the cells with 1NTO, 2NTO, 3NTO and 4NTO Ni0.9Fe0.1-supports, respectively. These values support the explanation of the durability testing results and indicate that the cell with 3NTO anode-support is the most resistant to carbon deposition among the cells investigated.

Discussion

According to previous studies19,27, the effectiveness of TiO2 on improving reforming activity can be attributed to its enhanced capability of H2O adsorption and consequently the coking resistance. It is the H2O adsorbed on the catalyst that increases the reforming activity19; and the prevalent presence of subsurface defects of TiO2 in reduced atmosphere, such as oxygen vacancies and Ti interstitials, enhances H2O adsorption due to surface relaxation and charge localization. On-cell methane reforming, constant adsorption of H2O in anode will shift the equilibrium reaction of Eqs (1) and (2) in a forward direction. Therefore, H2 and CO2 concentration increases whereas CO concentration decrease with increase in the amount of H2O. The increase in H2 concentration and the decrease in CO concentration subsequently prevent possible carbon formation by shifting Boudard reaction (Eq. 3) and decomposition of CH4 (Eq. 4) in a backward direction. In addition, the excess H2 reacts with oxygen ion from electrolyte to product electrical power and steam, which enhances the water-gas shift reaction and retards CH4 decomposition. In additional to the contribution of H2O adsorption on TiO2, the TiO2-supported Ni particles on the surface of Ni0.9Fe0.1 scaffold are also considered to increase the reforming activity, due to its known tendency to form a strong metal-support interaction (SMSI) between TiO2 support and Ni metal and widely used catalyst of CH4 and ethanol steam reforming16,28.

Based on the DRT shown in Fig. 6b and the results reported in a previous investigation25, five polarization processes were identified for individual cells, which are two high-frequency processes ascribed to the gas diffusion and charge transfer/ionic transport within the functional anode (P2A and P3A), one high-frequency process associated with oxygen surface exchange and bulk diffusion within the BSCF-LSM cathode (P2C), one low-frequency process related to mass transport in the Ni0.9Fe0.1-support (P1A) and one low-frequency process attributed to CH4 reforming in the Ni0.9Fe0.1-support (PRef). The contribution of each process to the total polarization resistance was obtained by data fitting the impedance spectra (Fig. 6a) using the complex nonlinear least-squares method and an equivalent circuit (inset in Fig. 6a) consisting of an ohmic resistor RO, two RQ elements for P2A and P3A, a Gerischer element (G) for P2C, a generalized finite length Warburg element (W) for P1A and another RQ element for PR. The change of the polarization resistance for each process, R1A, R2A, R3A, R2C and RRef, with the amount of loaded NTO is demonstrated in Fig. 6c. R3A and R2C remained almost unaffected by NTO infiltration, since the cathode was identical for all the cells, and the electrochemical reaction in the functional Ni-GDC anodes was the same reaction of H2 oxidation25 regardless of the amount of NTO loaded in the Ni0.9Fe0.1-support. The resistance of diffusion of reformate in the Ni0.9Fe0.1-support and Ni-GDC functional anode, R1A and R2A, decreased with increasing NTO amount till 3 wt.% and then increased at 4 wt.%, which reflects the amount change of H2 in the reformate. It is expected that higher concentration of H2 in the reformate lead to lower diffusion resistance in porous cell support and functional anode due to the high diffusivity of H2. RRef is assigned to CH4 steam reforming process; its change with the amount of loaded NTO in the Ni0.9Fe0.1-support is consistent with that of the reforming activity. According to the data-fitting results and discussions, it may be concluded that the cell performance improvement with NTO infiltration in the Ni0.9Fe0.1-support is attributed to the improved CH4 reforming activity and the decreased potential of carbon deposition; consequently the polarization resistances related to CH4 reforming and reformate transport processes are decreased.

NTO infiltration into Ni0.9Fe0.1-supports was investigated with the purpose of enhancing CH4 steam reforming activity, carbon deposition resistance and cell performance. Based on the obtained results and discussion, the following conclusions are drawn.

-

1

The activity of the Ni0.9Fe0.1-support for CH4 steam reforming is enhanced by infiltrated NTO, which is reduced into TiO2-supported Ni (0) particles in H2. The TiO2 improves the resistance to carbon deposition by adsorbing H2O, while the supported small Ni particles promote CH4 decomposition.

-

2

3 wt.% of the weight of the half cell (anode-support | functional anode | electrolyte) is the optimal value for the amount of NTO infiltrated into the Ni0.9Fe0.1-support. Increased CH4 reforming activity lead to the improvement of cell performance, durability and resistance to carbon deposition.

-

3

The overall cell polarization resistance is contributed by five polarization processes associated with CH4 reforming (Pref), mass transport in anode-support (P1A), gas diffusion in functional anode (P2A), charge transfer within functional anode (P3A), and oxygen surface exchange and bulk diffusion within cathode (P2C). The addition of NTO into the Ni0.9Fe0.1-support reduces the polarization resistance of Pref, P1A and P2A.

Methods

Cell fabrication

Ni0.9Fe0.1-supported cells were fabricated by tape casting-screen printing-sintering process. NiO (Haite Advanced Materials) and Fe2O3 (Sinopharm) powders were mixed at a Ni:Fe molar ratio of 9:1 and ball-milled for 24 h in xylene/ethanol solvent with fish oil (Richard E. Mistler, Inc.) as the dispersant, corn starch as the pore former, poly vinyl butyral (Solutia Inc.) as the binder and butyl benzyl phthalate and poly alkylene glycol (Solutia Inc.) as the plasticizer. The prepared slurry was cast into a tape with a dry thickness of ~1.2 mm, which was then die-cut into discs (25 mm in diameter) as the cell support, on which NiO (Inco)-GDC (10 mol.% Gd-doped CeO2, NIMTE, CAS) functional anode and GDC electrolyte were screen printed in sequence, followed by sintering at 1450 °C in air for 5 h. La0.8Sr0.2MnO3-coated Ba0.5Sr0.5Co0.8Fe0.2O3 (LSM-BSCF) cathode29 was then screen-printed on the sintered GDC electrolyte and sintered in air at 1050 °C for 2 h.

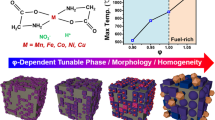

To introduce TiO2-supported Ni particles onto the stem of NiO-Fe2O3 scaffold (~40% porosity30), an aqueous solution containing Ti and Ni ions at the stoichiometric concentration of NiTiO3 (NTO) was prepared as follow. Tetrabutyl titanate (C16H36O4Ti, Sinopharm) was dissolved in a dilute nitric acid aqueous solution under stirring, and then stoichiometric amount of Ni nitrate (Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, Sinopharm) was added prior to the addition of citric acid (CA) and ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) as the chelants. The molar ratio of metal ions:CA:EDTA in the solution was 1:1:1.5. Ammonia solution was used to adjust the pH value of the solution to approximately 7. Such prepared solution was infiltrated into the pores of the sintered NiO-Fe2O3 scaffold and calcined in air at 1000 °C for 2 h to form crystallized NTO nano particles. This infiltration process was repeated to achieve the desired amounts of loaded NTO in the scaffold. The crystal structure of NTO and its chemical reactivity with NiO and Fe2O3 were determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD, X’Pert) using a NiO-Fe2O3-NTO powder mixture co-fired in air at 1000 °C for 2 h. The NTO powder was obtained by calcining the dried solution in air at 1000 °C for 2 h, and its reduced form (650 °C in H2 for 2 h) was characterized by XRD for phase identification and examined by using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, FEI sirion 200).

Steam reforming activity evaluation

To evaluate the catalytic activity of the infiltrated Ni0.9Fe0.1-support for CH4 steam reforming, the NiO-Fe2O3 support sintered at 1450 °C in air for 5 h was sealed in a ceramic housing using a CeramabondTM sealant (Aremco Product, Inc.) and reduced at 650 °C in H2 for 2 h. Then a mixture of 10% CH4, 10% H2O and 80% He was fed into the porous support at a constant rate of 100 ml min−1. The steam content in the mixture was controlled by flowing dry CH4 and He gases through a saturator containing distilled water at 50 °C according to the following equation31.

Compositional analysis of the effluent gas from the reactor was conducted with an on-line Pfeiffer Vacuum Mass Spectrometer. The steam reforming was performed at temperatures between 500 and 700 °C, and the CH4 conversion rate (X (%)) was estimated using the following equation.

Cell testing and characterization

The cell performance was evaluated at 650 °C with wet (3 mol.% H2O) CH4 as the fuel and ambient air as the oxidant at a flow rate of 100 ml min−1. Using a power supply of Solartron 1480A in 4-probe mode, the current density (i)–voltage (V)-power density (P) polarization curves were obtained at a scanning rate of 5 mVs−1 from 0 to 1 V, and electrochemical impedance spectra (EIS) were acquired within a frequency range from 100 KHz to 0.01 Hz and an AC signal amplitude of 10 mV. The microstructure of the cell was examined by using a SEM. The resistance to carbon deposition of (the amount of deposited carbon in) the Ni0.9Fe0.1-supported cell was characterized by temperature-programmed-oxidation (TPO) method at a flow rate of 20 ml min−1 of pure oxygen.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Li, K. et al. Enhanced methane steam reforming activity and electrochemical performance of Ni0.9Fe0.1-supported solid oxide fuel cells with infiltrated Ni-TiO2 particles. Sci. Rep. 6, 35981; doi: 10.1038/srep35981 (2016).

References

Chen, Y. et al. Direct-methane solid oxide fuel cells with hierarchically porous Ni-based anode deposited with nanocatalyst layer. Nano Energy. 10, 1–9 (2014).

Kan, H. & Lee, H. Enhanced stability of Ni–Fe/GDC solid oxide fuel cell anodes for dry methane fuel. Catalysis Communications, 12, 36–39 (2010).

Angeli, S. D., Monteleone, G., Giaconia, A. & Lemonidou, A. A. State-of-the-art catalysts for CH4 steam reforming at low temperature. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 39, 1979–1997 (2014).

Angeli, S. D., Pilitsis, F. G. & Lemonidou, A. A. Methane steam reforming at low temperature: Effect of light alkanes’ presence on coke formation. Catalysis Today, 242, 119–128 (2015).

Rakass, S., Oudghiri, H. H., Rowntree, P. & Abatzoglou, N. Steam reforming of methane over unsupported nickel catalysts. Journal of Power Sources, 158, 485–496 (2006).

Andersson, M., Paradis, H., Yuan, J. L. & Sunden, B. Review of catalyst materials and catalytic steam reforming reactions in SOFC anodes. International Journal of Energy Research. 35, 1340–1350 (2011).

Li, K. et al. Methane on-cell reforming in nickel–iron alloy supported solid oxide fuel cells. Journal of Power Sources, 284, 446–451 (2015).

Lu, M., Lv, P., Yuan, Z. & Li, H. The study of bimetallic Ni–Co/cordierite catalyst for cracking of tar from biomass pyrolysis. Renewable Energy. 60, 522–528 (2013).

Yang, R. T. & Chen, J. P. Mechanism of carbon filament growth on metal catalysts Journal of Catalysis. 115, 52–64 (1989).

Chen, Y. et al. Sm0.2(Ce1−xTix)0.8O1.9 modified Ni–yttria-stabilized zirconia anode for direct methane fuel cell Journal of Power Sources. 196, 4987–4991 (2011).

Wang, W., Jiang, S. P., TokA, I. Y. & Luo, L. GDC-impregnated Ni anodes for direct utilization of methane in solid oxide fuel cells. Journal of Power Sources. 159, 68–72 (2006).

Ding, D., Liu, Z., Li, L. & Xia, C. An octane-fueled low temperature solid oxide fuel cell with Ru-free anodes. Electrochemistry Communications. 10, 1295–1298 (2008).

La Rosa, D. et al. Mitigation of carbon deposits formation in intermediate temperature solid oxide fuel cells fed with dry methane by anode doping with barium. Journal of Power Sources. 193, 160–164 (2009).

York, A. P. E., Xiao, T., Green, M. L. H. & Claridge, J. B. Methane Oxyforming for synthesis gas production. Catalysis Reviews. 49, 511–560 (2007).

Yan, Q. G. et al. Activation of methane to syngas over a Ni/TiO2 catalyst. Applied Catalysis a-General. 239, 43–58 (2003).

Rossetti, I. et al. TiO2-supported catalysts for the steam reforming of ethanol Applied Catalysis a-General. 477, 42–53 (2014).

Adhikari, S., Fernando, S. D. & Haryanto, A. Hydrogen production from glycerin by steam reforming over nickel catalysts. Renewable Energy. 33, 1097–1100 (2008).

Shinde, V. M. & Madras, G. Catalytic performance of highly dispersed Ni/TiO2 for dry and steam reforming of methane. Rsc Advances. 4, 4817–4826 (2014).

Daté, M. & Haruta, M. Moisture effect on CO oxidation over Au/TiO2 catalyst. Journal of Catalysts. 201, 221–224 (2001).

Bradford, M. C. J. & Vannice, M. A. CO2 reforming of CH4 over supported Pt catalysts. Journal of Catalysts. 173, 157–171 (1998).

Tucker, M. C. Progress in metal-supported solid oxide fuel cells: A review. Journal of Power Sources. 195, 4570–4582 (2010).

Matus, Y., Dejonghe, L., Jacobson, C. & Visco, S. Metal-supported solid oxide fuel cell membranes for rapid thermal cycling. Solid State Ionics. 176, 443–449 (2005).

Park, H. C. & Virkar, A. V. Bimetallic (Ni–Fe) anode-supported solid oxide fuel cells with gadolinia-doped ceria electrolyte. Journal of Power Sources. 186, 133–137 (2009).

Leonide, A., Sonn, V., Weber, A. & Ivers-Tiffée, E. Evaluation and modeling of the cell resistance in anode-supported solid oxide fuel cells. Journal of the Electrochemical Society. 155, B36 (2008).

Kromp, A., Geisler, H., Weber, A. & Ivers-Tiffee, E. Electrochemical impedance modeling of gas transport and reforming kinetics in reformate fueled solid oxide fuel cell anodes. Electrochimica Acta. 106, 418–424 (2013).

Zhang, Y. X., Chen, Y., Yan, M. F. & Chen, F. L. Reconstruction of relaxation time distribution from linear electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Journal of Power Sources. 283, 464–477 (2015).

Aschauer, U. et al. Influence of subsurface defects on the surface reactivity of TiO2: water on anatase (101). J. Phys. Chem. C. 114, 1278–1284 (2010).

Rui, Z., Feng, D., Chen, H. & Ji, H. Anodic TiO2 nanotube array supported nickel–noble metal bimetallic catalysts for activation of CH4 and CO2 to syngas. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 39 16252–16261 (2014).

Meng, L. et al. High performance La0.8Sr0.2MnO3-coated Ba0.5Sr0.5Co0.8Fe0.2O3 cathode prepared by a novel solid-solution method for intermediate temperature solid oxide fuel cells. Chinese Journal of Catalysis. 35, 38–42 (2014).

Li, K. et al. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 39, 19747–19752 (2014).

Hua, B. et al. Oxidation behavior and electrical property of a Ni-based alloy in SOFC anode environment. Journal of the Electrochemical Society. 156, B1261 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by Natural Science Foundation of China (51472099 and 51672095). The SEM and XRD characterizations were assisted by the Analytical and Testing Center of Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.L., L.J. and X.W. conducted the experiments and prepared the manuscript; J.P. and J.L. provided suggestions to the experiments; B.C. initiated the study, discussed the results and revised the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Li, K., Jia, L., Wang, X. et al. Enhanced methane steam reforming activity and electrochemical performance of Ni0.9Fe0.1-supported solid oxide fuel cells with infiltrated Ni-TiO2 particles. Sci Rep 6, 35981 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep35981

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep35981

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.