Abstract

The Great East Japan Earthquake on 11 March 2011, caused the release of radioactive materials from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant (FDNPP), contaminating eastern Japan, particularly in part of Fukushima Prefecture. In 2012 and 2014, the radiocaesium concentration in brown rice did not exceed regulatory levels in Minamisoma City, Fukushima. However, in 2013, some radiocaesium concentrations in brown rice exceeded regulatory levels. In this work, autoradiograms showed that high radioactivity was present as contaminated spots on the panicles of rice and in brown rice in 2013. We evaluate the contribution of direct contamination to the radiocaesium concentration in brown rice and discuss the origin of radiocaesium contamination in brown rice using the 134Cs/137Cs radioactivity ratio. Here, we show that the main cause of the unexplained radiocaesium contamination of brown rice in Minamisoma City in 2013 is the adherence of radioactive materials to the rice panicles and these radioactive materials are associated with reactor units 2 or 3 of FDNPP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster caused by the Great East Japan Earthquake on 11 March 2011, released a large amount of radionuclides that polluted a wide area of eastern Japan. The contamination is of great concern for Japanese food safety. Immediately after the accident, the major radionuclides found in plants and environmental resources, such as soil and water, were 134Cs (half-life: 2.07 years), 137Cs (half-life: 30.1 years) and 131I (half-life: 8.02 days). By now, all the radioiodine has decayed. Thus, radiocaesium, particularly 137Cs, is of the greatest concern due to its relatively long half-life.

The Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW) has set provisional regulatory levels of 500 Bq kg−1 for radionuclides in food and the updated level of radiocaesium was set at 100 Bq kg−1 for general food, excluding infant food, milk, water and beverages, in April 20121. In Fukushima Prefecture, radiocaesium contamination in agricultural products is closely monitored before the products are shipped. The inspection of radiocaesium contamination in the rice produced in Fukushima Prefecture after the nuclear disaster in 2011 has been summarized by Nihei et al.2 Briefly, in Fukushima Prefecture, all brown rice in all bags for shipment must be inspected using a belt-conveyor-type radiocaesium concentration tester equipped with NaI or other types of scintillation counters2,3. In 2012 and 2013, 0.0007% and 0.0003% of rice bags exhibited values over 100 Bq kg−1, respectively4. However, none of the rice bags in 2014 had levels over 100 Bq kg−1 due to the implementation of effective countermeasures for inhibiting further uptake of radiocaesium by plants, such as the use of potassium fertilizer3.

In 2013 in Fukushima Prefecture, 28 of the approximately 11 million sampled bags of rice were identified as having excessive amounts of radiocaesium. Despite the use of countermeasures, 27 of the 28 bags had been produced in a limited area of Minamisoma City4. In this area, the radiocaesium concentration in brown rice did not exceed 100 Bq kg−1 in 2012 and 20144,5. The attachment of radioactive materials to the leaves and panicles of rice was detected by means of autoradiography, suggesting that the causes of the radiocaesium contamination of brown rice may be direct contamination (adherence to the aerial parts of plants and plant-based absorption) in addition to indirect contamination (absorption from soil and irrigation water)6.

In this report, we evaluate the effect of the direct contamination on the radiocaesium concentration in brown rice in Minamisoma City during 2013 and discuss the origin of the radiocaesium contamination of brown rice by examining the 134Cs/137Cs radioactivity ratio.

Results and Discussion

Rice radiocaesium contamination in 2013

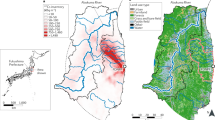

The area located up to 20 km north of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant (FDNPP), including the southern part of Minamisoma City and neighbouring Namie town, was subjected to an evacuation order (1 Oct 2014) and only rice farming for scientific studies in the selected paddy fields was permitted (Fig. 1)4. Thus, the central area of Minamisoma City coincided with the southern limit of the area north of FDNPP available for farming rice for human consumption.

Map showing the radiocaesium contamination in brown rice in Minamisoma City in 2013.

The grey areas represent areas subject to the evacuation order. The × symbols mark places where radioactivity concentrations in brown rice were over 100 Bq kg−1. The map was generated based on the data from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan (MAFF)4. The map was created using Adobe Photoshop Elements 13 and Microsoft PowerPoint 2013 software.

Brown rice with radiocaesium concentrations exceeding 100 Bq kg−1 in 2013 was detected in the southern area and part of the central area of Minamisoma City, located 12–21 km away from the FDNPP (Fig. 1)4. In the central area, where radiocaesium levels exceeding 100 Bq kg−1 were detected in 27 rice bags before shipment, the radiocaesium concentrations were higher in 2013 and lower in 20144,5. Of 1,589 bags, 43% had radiocaesium concentrations exceeding 50 Bq kg−1 in 20134, whereas none of the 1,955 bags had concentrations exceeding 50 Bq kg−1 and only one bag had a concentration exceeding 25 Bq kg−1 in 20144. The transfer factors (TFs) of radiocaesium from paddy field soil to brown rice (TF = radiocaesium concentration in brown rice (Bq kg−1)/radiocaesium concentration in the paddy field soil (Bq kg−1)) in the southern area are shown in Table 1. The TFs in 2013 ranged from 0.06 to 0.58 (Table 1). According to Kato et al.7 the TF values of brown rice ranged from 0.00082 to 0.037 in Fukushima and neighbouring prefectures in 2011 shortly after the FDNPP accident. The TF values in 2014 were within the range of values reported by Kato et al.7, whereas those in 2013 were much higher (Table 1). Therefore, it is not plausible that indirect contamination was the main source of the contamination of brown rice in Minamisoma City in 2013.

Cause of rice radiocaesium contamination

Figure 2 shows autoradiograms of the panicles, brown rice and husks of the highly contaminated rice samples collected in 2013. Black dots on the autoradiograms indicate the presence of radioactive materials. High-intensity spots were visible on the panicles (Fig. 2a). Brown rice also showed high radioactivity at positions corresponding to the high-intensity spots on the panicles (Fig. 2c). In all 40 brown rice samples with high levels of radiocaesium contamination in the southern area and part of the central area in 2013, high radioactivity was observed as numerous spots on the autoradiogram. In contrast to the samples in 2013, no radioactive spots were observed on the brown rice samples in 2014.

Autoradiography of rice in 2013.

(a) Superimposition of autoradiogram and photograph of panicles. The dotted red circles are the potassium chloride markers. (b) Photographs of the rachis branches surrounded by red dotted rectangles A and B in Fig. 2a. (c) Superposition of autoradiogram and photograph of brown rice and husks. The sample numbers of the unhulled rice are shown and correspond to those in Fig. 2b.

To evaluate the effect of the direct contamination on the radiocaesium concentration in brown rice in Minamisoma City in 2013, the grains of the brown rice samples with high radiocaesium concentrations in the southern area were divided into highly contaminated grains and less contaminated grains after 2 weeks of exposure on an imaging plate. Brown rice grains at positions corresponding to visible spots on the autoradiogram were isolated as highly contaminated grains. The radiocaesium concentrations in the highly contaminated grains were 17- to 48-fold (average of 29-fold) higher than those in the less contaminated grains (Table 1). If the radiocaesium in the highly contaminated grains originated from soil, irrigation water, or foliar contamination, the distribution of radiocaesium concentrations on the panicles and the brown rice should be even higher (Fig. 2a,c and Table 1). The radiocaesium contamination can be attributed to the contamination of the flowers because the radioactive materials that adhere to the rice flowers are directly incorporated into rice grains, which may cause a substantial increase in the radiocaesium concentration of rice grains8.

Although the highly contaminated grains contributed to 2–8% of the total weight, the percentage contribution of the highly contaminated grains to the total radiocaesium activity was estimated to be more than 41% and the removal of highly contaminated grains caused a large decrease in the radiocaesium concentration in the brown rice samples (Table 1). These results show that the adherence of radioactive materials to the rice panicles was the main cause of the radiocaesium contamination.

Origin of radiocaesium on the panicles

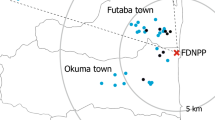

If the radioactive materials that adhered to the rice in 2013 originated from the areas where the radiocaesium concentration levels exceeded 100 Bq kg−1, the radiocaesium contamination in brown rice should also have been present in 2014 and in subsequent years. However, highly contaminated grains were not found in 2014. Therefore, the radioactive materials are not likely to have originated from these areas. Figure 3a shows the spatial distribution of the radiocaesium concentrations in brown rice in 2013 reported by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan (MAFF)4. According to this report, the radiocaesium concentrations in brown rice were highest in the southern area of Minamisoma City and they generally decreased towards the northern area, suggesting that the source of radiocaesium contamination in 2013 was the southern area of Minamisoma City.

Spatial distribution of 134 + 137Cs concentrations in brown rice in 2013 and 134Cs/137Cs radioactivity ratio of paddy field soil.

Grey areas represent areas subject to the evacuation order. (a) 134+137Cs concentrations (Bq kg-1) of brown rice in 2013 and (b) 134Cs/137Cs radioactivity ratios of paddy field soil. Figure 3a was generated based on the data from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan (MAFF)3. The map was created using Adobe Photoshop Elements 13 and Microsoft PowerPoint 2013 software.

In the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster on March 2011, hydrogen explosions occurred in reactor units 1, 2 and 3, releasing radioactive materials into the environment. Komori et al.9 reported that the 134Cs/137Cs radioactivity ratios of reactor units 1, 2 and 3 were 0.91 (0.89–0.93), 1.00 (0.96–1.05) and 1.01 (0.97–1.04), respectively. Therefore, these values could be used to identify the origin of the radiocaesium contamination. Figure 3b shows the spatial distribution of the 134Cs/137Cs radioactivity ratio of paddy field soil collected over a wide area of Minamisoma City. The 134Cs/137Cs radioactive ratio was time-corrected for each radioactive half-life to the value of the FDNPP accident on March 11, 2011, as described by Komori et al.9 The values of the 134Cs/137Cs radioactivity ratio of the paddy field soil ranged from 0.89 to 0.97 and gradually increased from the southern area to the northern area (Fig. 3b). These results indicate that the direct deposition of the radioactive aerosol released from the reactor unit of FDNPP on March 2011 varied across Minamisoma City. Our results showed that the paddy field soils in the southernmost part of the city were strongly affected by radioactive materials released from reactor unit 1.

If the radiocaesium in the brown rice was from the paddy field soil, the values of the 134Cs/137Cs radioactivity ratio of brown rice should be close to those of the paddy field soils because no isotope effect for caesium exists in the natural environment. The 134Cs/137Cs radioactivity ratios of brown rice in the southernmost section of the city in 2014 were close to those of the paddy field soil and similar to the ratio for reactor unit 1 (Table 3). In contrast, in 2013, the average value of the 134Cs/137Cs radioactivity ratio of highly contaminated grains was approximately 1.0, which was significantly higher than that of paddy field soil (0.92) and similar to the ratios for reactor units 2 and 3 (Table 3). These results show that in the southernmost section of Minamisoma City, the radioactive materials that adhered to the panicles in 2013 were not from the paddy field soil but rather were associated with reactor units 2 and 3 of FDNPP. Although it is difficult to estimate the origin of radiocaesium contamination using the 134Cs/137Cs radioactivity ratio, in areas where the radioactive materials associated with reactor units 2 and 3 contaminated the grains and the paddy field soils (Fig. 3b), the 134Cs/137Cs radioactivity ratio of the highly contaminated grains in 2013 was also approximately 1.0.

Based on these results, we conclude that the main cause of the unexplained radiocaesium contamination of brown rice in Minamisoma City in 2013 was the adherence of radioactive materials to the rice panicles and these radioactive materials, which appear to have originated from the southern area of Minamisoma City when the rice was flowering, were associated with reactor units 2 or 3 of FDNPP.

On 19 August 2013, the air dose rates increased at five measuring points 2.8 to 8.3 km north-northwest on the leeward side of FDNPP10 and high activity concentrations in the air were detected at the air filter station in the central area of Minamisoma City in the week of 15 August to 22 August 201311. In the same week, debris removal operations were conducted at reactor unit 3 of FDNPP and radioactive dust under the debris was spread outside of FDNPP12. Although the origin of radiocaesium on the panicles in 2013 is still unclear, it is likely that the debris removal operations led to the unexplained radiocaesium contamination of brown rice.

Methods

We identified radiocaesium contamination in rice by autoradiography and estimated the 134Cs/137Cs radioactivity ratio in brown rice and soil samples by gamma-ray spectrometry.

Autoradiography

The panicle and brown rice samples were collected from areas of Minamisoma City where radiocaesium concentrations exceeding 100 Bq kg−1 were detected in 2013. An imaging plate (BAS-SR2040, Fuji-Film, Japan) and a reading system (Typhoon FLA 7000, GE Healthcare Bio-Science Corp., USA) were used to obtain and analyse the images of panicles and brown rice samples. The panicle samples were fixed onto 42 × 30-cm cardboard pieces with cellophane tape. After covering the samples with polyvinylidene chloride resin film (Saran wrap, AsahiKASEI, Japan), potassium chloride markers were attached to the corners of the film to allow the autoradiogram and the photograph (or the cardboard-mounted samples) to be superimposed. The markers were made by packing potassium chloride (10 or 26 mg) into a frame, which was created by cutting a silicon tube with a 6-mm inside diameter into a 1-mm-thick round slice. The filled frame was sealed inside a laminated pouch. The cardboard-mounted panicle samples were exposed to an imaging plate in the dark for 2 days to evaluate the contamination state and the imaging plates were scanned at a spatial resolution of 25 μm with the reading system. The unhulled rice on the rachis branch was separated into brown rice and husks. The brown rice and husks were fixed onto cardboard with double-sided tape and exposed to an imaging plate for 3 days.

To evaluate the effect of the direct contamination of brown rice by radiocaesium, the brown rice grains in each sample from the southern area of Minamisoma City with high levels of radiocaesium contamination were divided into highly contaminated grains and less contaminated grains. Brown rice (80 g, approximately 4000 grains) was affixed to a piece of cardboard with spray adhesive (3 M Super 77 Multipurpose Spray Adhesive, 3 M Japan Limited, Japan) and then exposed to an imaging plate for 2 weeks to isolate the highly contaminated grains as much as possible. Visible spots with the radioactivity in the samples and the markers on the autoradiogram of brown rice were traced onto the clear plastic sheet and the sheets were superimposed accurately on the cardboard-mounted brown rice samples at marked positions. The spots on the autoradiogram were several times larger than the actual grains due to the sample thickness and because the radiation was emitted in all directions. Therefore, it was difficult to distinguish the highly contaminated grains from neighbouring less contaminated grains. Accordingly, the grains of interest were selected, set at appropriate intervals on another piece of cardboard with double-sided tape and exposed to an imaging plate for a further 2 weeks to confirm their high radioactivity. In total, 320–400 g of each of the brown rice samples was used to identify highly contaminated grains. Each group was weighed, pulverized and then placed in a cylindrical polypropylene container (U-8 container, 65 mm in height and 50 mm in diameter).

Gamma-ray spectrometry

The radionuclide concentrations and the 134Cs/137Cs radioactivity ratio of the brown rice and soil samples were determined with high-purity germanium (HPGe) detectors with relative efficiencies of 25% and 40%, respectively (GC2520-7500SL and GC4020-7500SL, Canberra, USA). The radiocaesium concentrations and 134Cs/137Cs radioactivity ratio of the brown rice samples in the study area were measured with a U-8 container and a 0.7 L Marinelli beaker, respectively, in 2013 and 2014.

Paddy field soil samples from the surface to a depth of 15 cm were collected over a wide area of Minamisoma City. Soil samples were air-dried and passed through a 2-mm screen and plant residues were removed prior to gamma-ray spectroscopy. The radiocaesium concentrations and 134Cs/137Cs radioactivity ratio of the soil samples were measured in a U-8 container.

The concentration of 137Cs was directly determined using gamma lines at 661.6 keV. In contrast to 137Cs, 134Cs emits multiple gamma-rays. The largest emission rate of 134Cs gamma-rays was 98% at 604.7 keV and 86% at 795.9 keV. The 134Cs concentration is determined from the weighted average of gamma-ray counting at the two gamma lines13. By means of gamma-ray counting for a long period of time, the counting uncertainties (relative standard deviation) of 134Cs and 137Cs were maintained below 1%, except for the less contaminated grains in 2013. Counting times were from 81,794 to 1,843,654 s for brown rice samples (the highly contaminated grains in 2013 and brown rice in 2014) and from 3,788 to 309,033 s for soil samples. The detection efficiencies of the HPGe detectors were determined with approximately 5% uncertainty using a set of activity standard volume sources (MX-033, Japan Isotope Association). This uncertainty uniformly contributes to the systematic error of all measurement results and can be distinguished from the random error due to the counting of gamma-rays emitted from a sample. The self-absorption of gamma-rays was adequately corrected based on the thickness and density of the sample and the attenuation coefficients of gamma-rays. Furthermore, the coincidence-summing correction of gamma-rays emitted from 134Cs was performed using the peak-to-total calibration method14. The radionuclide concentrations in the samples were time-corrected to the values on 1 October of each year, the conventional harvest time for rice in Fukushima, by each radioactive half-life. However, the 134Cs/137Cs radioactivity ratio of the samples was corrected to the values on 11 March 2011, the time on which the nuclear reactor at the FDNPP was scrammed. The uncertainty of the 134Cs/137Cs ratio was calculated by means of the propagation of counting uncertainties.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Matsunami, H. et al. Evaluation of the cause of unexplained radiocaesium contamination of brown rice in Fukushima in 2013 using autoradiography and gamma-ray spectrometry. Sci. Rep. 6, 20386; doi: 10.1038/srep20386 (2016).

References

Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, New Standard limits for Radionuclides in Foods. (2011) Available at: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/topics/2011eq/dl/food-120821_1.pdf. (Accessed: 4th December 2015).

Nihei, T., Tanoi, K. & Nakanishi, T. M. Inspection of Radiocesium Concentration Levels in Rice from Fukushima Prefecture after the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant Accident. Sci. Rep. 5, 8653, doi: 10.1038/srep08653 (2015).

Fukushima-no Megumi Anzen Taisaku Kyogikai: Bounty of Fukushima Safety Council (inspection of all rice). (2012) Available at: https://fukumegu.org/ok/kome/. (Accessed: 4th December 2015).

Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Results of all rice inspection and research on the cause of radiocesium contamination of brown rice in Minamisoma City in 2013. (2014) Available at: http://www.maff.go.jp/j/kanbo/joho/saigai/fukusima/pdf/genmai_h26_0214.pdf. (Accessed: 4th December 2015) (In Japanese).

Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Research results on the cause of radiocesium contamination of brown rice in Minamisoma City in 2013. (2014) Available at: http://www.maff.go.jp/j/kanbo/joho/saigai/fukusima/pdf/genmai_kousatu_141201.pdf. (Accessed: 4th December 2015) (In Japanese).

FAO Expert Committee, Rome. Radioactive materials in food and agriculture. FAO Atomic Energy Series No. 2, 35–65 (1960).

Kato, N. et al. Potassium fertilizer and other materials as countermeasures to reduce radiocesium levels in rice: Results of urgent experiments in 2011 responding to the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition. 61, 179–190 (2012).

Tsumura, A., Komamura, M. & Kobayashi, H. Behavior of Radioactive Sr and Cs in Soils and Soil-plant Systems. Bull., Natl. Inst. Agric. Sci., Ser. B. 36, 57–113 (1984) (In Japanese with English summary).

Komori, M., Shozugawa, K., Nogawa, N. & Matsuo, M. Evaluation of Radioactive Contamination Caused by Each Plant of Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station Using 134Cs/137Cs Activity Ration as an Index. Bunseki Kagaku. 62, 475–483 (2013) (in Japanese with English summary).

Fukushima Prefecture, Transient increase in air dose rate around the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in August 2013. The second report. (2013) Available at: https://www.pref.fukushima.lg.jp/download/1/20130827moni.pdf.pdf. (Accessed: 4th December 2015) (In Japanese).

Steinhauser, G. et al. Post-accident sporadic releases of airborne radionuclides from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant site. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 14028–14035, doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b03155 (2015).

Tokyo Electric Power Company, Estimation of radioactive material released during the debris removal operations at the reactor unit 3 of Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in August 2013. (2014) Available at: http://www.nsr.go.jp/data/000051136.pdf. (Accessed: 4th December 2015) (In Japanese).

Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Gamma-ray spectrometry with germanium semiconductor detectors, Standard Radiological Methodology Series No.7, 156 (2002) (In Japanese).

Ababneh, A. M. & Eyadeh, M. M. Coincidence summing corrections in HPGe gamma-ray spectrometry for Marinelli-beakers geometry using peak to total (P/T) calibration. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci., 8, 323–327 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Fukushima Agricultural Technology Centre for collecting the samples, Ms. Yurie Yoshida, Mr. Yoshihiko Takahashi and Ms. Mikiko Saito of the Agricultural Radiation Research Center, NARO/TARC, for their help with the autoradiography and gamma-ray spectrometry, Dr. Katsumi Shozugawa,Graduate School of Arts and Science, The University of Tokyo, for his advices in the gamma-ray spectrometry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.M. and T.M. designed the study, conducted the analysis and analysed the results. H.F and T.S. provided advice on the experimental approach. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Matsunami, H., Murakami, T., Fujiwara, H. et al. Evaluation of the cause of unexplained radiocaesium contamination of brown rice in Fukushima in 2013 using autoradiography and gamma-ray spectrometry. Sci Rep 6, 20386 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20386

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20386

This article is cited by

-

Detecting radioactive particles in complex environmental samples using real-time autoradiography

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Adsorptive removal of cesium using surface-modified petroleum residue pitch with NaClO

Carbon Letters (2024)

-

137Cs transfer from soils contaminated by resuspended particles to Japanese mustard spinach in difficult-to-return zone of Fukushima

Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry (2023)

-

Secondary radiocesium contamination of agricultural products by resuspended matter

Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry (2018)

-

Transfer of radiocesium from the upper part of rice plants after treatment at different growth stages

Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.