Abstract

Here, we propose a novel DNA-based doping method on MoS2 and WSe2 films, which enables ultra-low n- and p-doping control and allows for proper adjustments in device performance. This is achieved by selecting and/or combining different types of divalent metal and trivalent lanthanide (Ln) ions on DNA nanostructures, using the newly proposed concept of Co-DNA (DNA functionalized by both divalent metal and trivalent Ln ions). The available n-doping range on the MoS2 by Ln-DNA is between 6 × 109 and 2.6 × 1010 cm−2. The p-doping change on WSe2 by Ln-DNA is adjusted between −1.0 × 1010 and −2.4 × 1010 cm−2. In Eu3+ or Gd3+-Co-DNA doping, a light p-doping is observed on MoS2 and WSe2 (~1010 cm−2). However, in the devices doped by Tb3+ or Er3+-Co-DNA, a light n-doping (~1010 cm−2) occurs. A significant increase in on-current is also observed on the MoS2 and WSe2 devices, which are, respectively, doped by Tb3+- and Gd3+-Co-DNA, due to the reduction of effective barrier heights by the doping. In terms of optoelectronic device performance, the Tb3+ or Er3+-Co-DNA (n-doping) and the Eu3+ or Gd3+-Co-DNA (p-doping) improve the MoS2 and WSe2 photodetectors, respectively. We also show an excellent absorbing property by Tb3+ ions on the TMD photodetectors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) nanostructures are currently being considered one of the promising materials for next-generation nanotechnology owing to the self-assembly and highly selective binding properties of DNA, which are based on the Watson-Crick complementary rules1,2,3,4,5. The self-assembled DNA nanostructures have been recently used in various nanoscale research fields, such as spintronics6,7, nanoelectronics8,9, biosensors10,11 and nanophotonics12,13. In particular, due to the highly selective binding property of DNA nanostructures, various particles such as metal nanoparticles (NPs)14,15, protein molecules16, nanowires (NWs)17 and divalent metal ions18,19,20,21 have been successfully incorporated onto the bases and backbone sites of DNA, eventually functionalizing the DNA nanostructures. Braun et al.22 and Maune et al.23 also reported self-assembled single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) bound on natural and origami DNA templates.

Meanwhile, transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) with a two-dimensional layered structure, such as molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) and tungsten diselenide (WSe2), have been considered highly promising materials for next-generation flexible, wearable, stretchable and transparent devices due to their unique physical, electrical and optical properties24,25,26,27,28,29,30. TMD-based electronic devices are immune to short-channel effects owing to their excellent thickness scalability down to an atomic monolayer and the van der Waals epitaxial structure without dangling bonds24,25. Moreover, TMD materials are also expected to be suitable in optoelectronic applications because of their tunable energy bandgap property which is controllable by layer thickness (from 1.8 eV to 1.2 eV) and noble quantum efficiency28,29,30. In particular, recent studies on TMD devices have focused on developing a suitable doping technique because precise control of the threshold voltage (VTH) and the number of tightly-bound trions31 as well as very low contact resistance are required to achieve high performance. It is especially critical to develop an ultra-low level doping technique for the proper design and optimization of TMD-based devices (VTH for transistors and tightly-bound trions for photodetectors) because high level doping (about 1012 cm−2) causes TMD to act as a near-metallic layer. However, it is difficult to apply an ion implantation technique to TMD materials to achieve low-level doping due to crystal damage that occurs during the implantation process. Although safe doping techniques have recently been developed which can be applied to TMDs with an atomic layer structure, most of the previous TMD doping techniques employing potassium32, Au NPs33, polyethyleneimine (PEI)34, functional self-assembled monolayers (SAMs)35 and plasma treatment with fluorine (F) or oxygen (O)36 presented very high doping levels of ~1012 cm−2. Recently, low-level n- and p-doping of TMD materials was achieved using cesium carbonate (Cs2CO3)37, octadecyltrichlorosilane (OTS)38 and M-DNA39, but further studies are needed to reduce the doping level down to an intrinsic level.

Here, we demonstrate a novel DNA-based doping method on selected 2D TMD materials (MoS2 and WSe2, which represent n- and p-channel materials, respectively), enabling ultra-low-level n- and p-doping control, which had not been previously accomplished. This is achieved by selecting and/or combining different types of positive ions on DNA nanostructures. The DNA is functionalized by trivalent lanthanide ions (Ln-DNA) or both divalent metal and trivalent lanthanide ions (Co-DNA), which is newly proposed in this work. Since the phosphate backbone (PO4−) in DNA causes n-doping on the TMD films by attracting and holding hole carriers on the side of TMD, various selections and/or combinations of divalent and trivalent positive ions on DNA make it possible to achieve both very low-level n- and p-doping, which are very close to the intrinsic level. First of all, Ln-DNA nanostructures based on double-crossover (DX) DNA lattices are explored as a function of ion concentration (here, Gd3+) through Raman spectroscopy and atomic force microscopy (AFM) analyses. We then investigate low-level n- and p-doping phenomena on MoS2 and WSe2 by Ln-DNA and Co-DNA in terms of the performance (threshold voltage, on-/off-currents, photoresponsivity and detectivity) of electronic and optoelectronic devices using Raman spectroscopy, photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy and electrical/optical measurements (ID − VG with/without exposure to 655-nm, 785-nm and 850-nm lasers). We also discuss the absorption of trivalent lanthanide (Ln) ions with/without DNA templates with respect to the specific wavelengths of light and its influence on the performance of Ln-DNA or Co-DNA-doped TMD optoelectronic devices.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and analysis of Ln-DNA nanostructures

As shown in Fig. 1a, we formed a DNA double-crossover (DX) lattice structure with various concentrations of lanthanide ions and then investigated its stability by Raman spectroscopy and AFM to avoid structural deformation of the DX lattices. The DNA DX lattices were fabricated by a conventional solution-free annealing process. After annealing at 95 °C, various concentrations of Ln ions were added into the DX lattice solution (0, 0.5, 1 and 2 mM of Eu3+, Gd3+, Tb3+ and Er3+). In order to verify the stability of Gd-DNA, which is Ln-DNA with various concentrations of Gd3+, we obtained Raman spectra of Gd-DNA grown on glass substrate (Fig. 1b) and identified peak differences between 0 mM (pristine DNA), 0.5 mM, 1 mM and 2 mM of [Gd3+]. In the pristine DNA crystal without Gd3+, Raman peak signals were observed at 1246 and 1420 cm−1 for adenine (A), 770 and 1469 cm−1 for thymine (T), 931 and 1590 cm−1 for guanine (G), 618, 655 and 1348 cm−1 for cytosine (C) and 1066 and 1145 cm−1 for the phosphate backbone (PO4−)40,41. After binding Gd3+ ions onto the base pairing and backbone sites, the Raman intensity related to base and backbone sites was reduced. In particular, a Raman peak shift was observed in the base pairing sites only when the concentration of [Gd3+] was above 0.5 mM. Because the Ln ions (including Gd3+) were reported to be normally attached to backbone sites due to its ionic radius (300 ~ 340 pm), which is larger than the hydrogen bonding length (340 pm) in DNA bases42, it is thought that the Ln ions are intercalated in the bases without chemical bonding and therefore seem to influence the DNA nanostructure. As the concentration of [Gd3+] increased, the Raman peak intensity of Gd-DNA decreased and it was eventually hard to identify Raman peaks of Gd-DNA above 1 mM of [Gd3+], indicating that the Gd-DNA crystal structure is deformed when more than 1 mM [Gd3+] ions are added. This was verified once again through AFM images of Gd-DNA with 0 mM (pristine DNA), 0.5 mM and 2 mM of [Gd3+] in Fig. 1c. The AFM images of pristine and Gd (0.5 mM) samples showed polycrystalline structures without deformation and the clear periodicity of each DX lattice was also confirmed in the noise-filtered 2D spectrum image after fast Fourier transform (FFT). However, in the case of 2 mM [Gd3+], Gd-DNA complexes seemed to be aggregated and consequently form an amorphous structure. A similar phenomenon was also observed in the cases of other Ln ions with different concentrations and the determined optimum concentrations of each Ln ion were 1 mM for [Eu3+], 1 mM for [Gd3+], 1 mM for [Tb3+] and 1 mM for [Er3+].

Schematic diagrams showing the Ln-DNA DX lattice fabrication process and the Raman spectra and AFM images of Ln-DNA with various concentrations of lanthanide ions.

(a) Schematic diagrams of Ln-DNA DX lattice fabrication. (b) Raman spectra of DNA and Gd-DNA with 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 mM of Gd3+ ions. (c) AFM images of pristine DNA and Gd-DNA with 0.5 and 2.0 mM Gd3+. Inset: Noise-filtered 2D spectrum images constructed by Fast Fourier Transform showing a crystalline nature with clear periodicity of DNA lattices with 0.5 mM of Gd3+ and an amorphous nature without periodicity of DNA with 2.0 mM of Gd3+.

Raman analysis of TMD films doped by Ln-DNA or Co-DNA

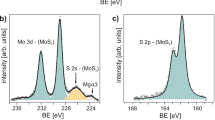

The artificially designed Ln- or Co-DNA DX solution was dropped and dried five times on the MoS2 and WSe2 surfaces. DNA nanostructures were homogeneously dispersed along the surface of MoS2 and WSe2 because of the self-aligning capability of the DNA39. In the previous study, the PO4− backbone sites in DNA nanostructures were reported to induce and hold positive charges (holes) at the interface region in the side of the TMD, resulting in n-doping (Fig. 2a). In the case of Ln-DNA, Ln ions are predominantly attached in the DNA backbone sites due to their relatively larger ionic radii so that the attached Ln ions are expected to compete with the negative charges of base pairings, leading to relatively light n- or p-type doping on TMD films. This would be expected because previous research showed a reduction in the p-type doping level of M-DNA by using a metal ion with a relatively larger ionic radius39. Raman analysis was then performed on the Ln-DNA-doped TMD samples to investigate the Ln-DNA doping effects by Eu3+, Gd3+, Tb3+ and Er3+ ions on TMD films, as shown in Supplementary Information Fig. S3. In the MoS2 films, two conventional peaks (E12g and A1g) were observed at ~380 cm−1 and ~406 cm−1, which respectively indicate the in-plane and out-of-plane vibrations for bulk MoS243. On the other hand, only a single peak was obtained at ~250 cm−1 in WSe2 films because both the E12g and the A1g modes for WSe2 are close to 250 cm−1 44. To clarify the degree of Ln-DNA doping by each ion on TMD films, we extracted the peak shift values in E12g, A1g and E12g + A1g before and after Ln-DNA doping and we plotted the values in Fig. 2b,c. Here, we prepared 10 different samples in each doping condition for Raman analysis and measured at five different points in each sample. As shown in Fig. 2b,c, a red-shift phenomenon occurred in the E12g, A1g and E12g + A1g peaks which have respectively peak shift values in the ranges of −1.3 ~ −0.8 cm−1, −1.2 ~ −0.7 cm−1 and −1.3 ~ −0.9 cm−1, indicating that very low level n-type doping was achieved on the TMD films. This n-type doping phenomenon by Ln-DNA also seems to be slightly weaker than that by pristine DNA. For reference, a blue-shift phenomenon in all of the peaks was observed after the M-DNA doping on the MoS2 and WSe2 films (2.8 ~ 5.0 cm−1 for E12g, 3.8 ~ 5.2 cm−1 for A1g and 3.1 ~ 5.1 cm−1 for E12g + A1g)39, indicative of p-type doping.

Next, we added Cu2+ ions with a relatively smaller ionic radius into Ln-DNA to acquire weaker n- or p-type doping effects on TMD films by converting the negative charges at the base pairings to positive charges; these new DNA nanostructures are referred to as Co-DNA. Here, the Cu2+ ions are expected to be bound at DNA base pairings because the Ln ions are predominantly attached to the backbone sites, eventually modulating the strength of the total charge which previously showed weak negative polarity. In this Co-DNA experiment, the different amounts of Ln ions (0.5 mM Eu3+, 0.5 mM Gd3+, 0.5 mM Tb3+, or 0.5 mM Er3+) were mixed with 2 mM of Cu2+ ions to avoid structural deformation of Co-DNA nanostructures. Then, Raman spectroscopy was performed on the DNA (pristine), Ln-DNA (by Gd3+) and Co-DNA (by Gd3+ and Cu2+) structures, as shown in Fig. 3b. As previously mentioned, the intensity of Raman peaks, indicating the base pairing and backbone sites of DNA, was reduced in the case of Gd-DNA due to the Gd3+ ions attached on the sites. When Cu2+ ions were added into the Gd-DNA, we observed an additional reduction in all of the peaks related to base pairings and backbone sites, indicating that Cu2+ ions were additionally attached on the remaining backbone sites as well as the base pairings; it was previously predicted that Ln ions were not bound to the base pairings. Finally, we coated the various Co-DNA nanostructures on MoS2 and WSe2 films and performed Raman analysis on the films. The raw Raman peak data of Co-DNA-doped MoS2 and WSe2 can be found in Supplementary Information Fig. S3. Figure 3c,d show the extracted peak shift values before/after Co-DNA doping for MoS2 (ΔE12g and ΔA1g) and WSe2 (ΔE12g + A1g), respectively. Here, the Raman measurement was performed on fifty different points in each sample. For both the MoS2 and WSe2 cases, Co-DNA nanostructures with Tb3+ or Er3+ ions seem to induce much weaker n-type doping phenomena compared to the previous Tb- and Er-DNA (Ln-DNA). This is because smaller peak shift values were observed in the peaks (−0.5 ~ −0.7 cm−1 for E12g, −0.3 ~ −0.5 cm−1 for A1g and −0.2 ~ −0.4 cm−1 for E12g + A1g). Meanwhile, a blue-shift phenomenon was confirmed in the MoS2 and WSe2 films doped by Co-DNA with Eu3+ or Gd3+ ions, indicating that the films were lightly p-doped. Here, the peak shift values are 0.3 ~ 0.1 cm−1 for E12g, 0.6 ~ 0.4 cm−1 for A1g and 0.45 ~ 0.4 cm−1 for E12g + A1g, which are much smaller than the previously reported values of M-DNA-doped flims24. These results support the claim that the Cu2+ ions are bound at DNA base pairings (also, remained backbone sites) and can be used to modulate the strength of total charge in Ln-DNA, eventually making the Co-DNA nanostructure show weak negative or positive polarity. In particular, based on the ionic radius and optimum concentrations shown in Table 1, it is thought that Eu3+ ions show the strongest positive charge due to their largest ionic radius and highest concentration. As expected, the largest peak shift was observed in the MoS2 and WSe2 films doped by Co-DNA with Eu3+ ions. In contrast to the Eu3+ sample, the smallest peak shift, indicating light n-type doping, was obtained in the TMD films doped by Co-DNA with Er3+ ions which are expected to show the lowest positive charge strength owing to the smallest ionic radius.

Electrical characteristics of Ln-DNA- and Co-DNA-doped TMD electronic devices

We then fabricated TMD electronic devices (back-gate transistors) and investigated the electrical properties (threshold voltage, 2D sheet carrier concentration and on-current) of TMD devices before/after Ln-DNA or Co-DNA doping. Figure 4 shows the schematic diagram of TMD transistors and the energy band diagrams of metal-undoped/doped TMD junctions in the source-side when proper operating biases (positive VDS for MoS2 and negative VDS for WSe2) are applied. When Ln-DNA is coated on TMD films, as already explained, the negative charges of Ln-DNA are expected to hold hole carriers at the interface between Ln-DNA and TMD, resulting in an n-type doping phenomenon. In the case of MoS2, as shown in Fig. 4b, the electric field at the source-side Ti-MoS2 junction is predicted to increase due to the down-shift of MoS2 energy bands by Ln-DNA doping, thereby reducing the effective barrier height of the Ti-MoS2 junction (Schottky barrier lowering effect: ФControl,eff > ФLn3+,eff). As a result, more electron carriers may be injected from Ti to MoS2 and this result in a negative shift in VTH. In addition, it is also predicted that the WSe2 energy band shifts down after Ln-DNA doping. Subsequently, the effective hole barrier height from the source to WSe2 increases, finally causing a negative shift in VTH. On the other hand, because Co-DNA shows very weak positive polarity (Eu3++Cu2+ or Gd3++Cu2+) or negative polarity (Tb3++Cu2+ or Er3++Cu2+), it is possible to hold electron or hole carriers at the interface, respectively, eventually causing very low level n- or p-type doping. In particular, the level of n-doping by Tb- or Er-based Co-DNA is expected to be lower than that by Ln-DNA. In MoS2, Eu- or Gd-based Co-DNA moves up the MoS2 energy band, consequently reducing the electric field at the source-side junction and increasing the effective electron barrier height (green line; a positive shift in VTH). In contrast, Tb- or Er-based Co-DNA causes n-doping on MoS2, thereby shifting down its energy band and eventually decreasing the effective electron barrier height (pink line; a negative shift in VTH). A similar phenomenon in the effective hole barrier height and VTH is also expected on WSe2, as shown in the right-bottom of Fig. 4b.

Figure 5a shows ID − VG characteristics of undoped and Gd-DNA-doped MoS2, which were measured at VDS = 5 V. As previously predicted, a negative shift in VTH (from −28.5 V to −31.2 V) and an increase in on-current (from 2.3 × 10−6 A/μm to 1.2 × 10−5 A/μm) were observed after the Gd-DNA doping, indicating that the Gd-DNA caused n-type doping of MoS2. These changes are attributed to an increase in the tunneling probability from the source to the MoS2 channel by the Gd-DNA doping. These changes in VTH and on-current were also observed in the other Ln-DNA with Eu3+, Tb3+, or Er3+ ions, as shown in Fig. 5b,c. The extracted ∆VTH (=VTH_Ln-DNA − VTH_Control) values were between −1 and −2.5 V, indicating the n-doping of MoS2, which is also consistent with the previous Raman analysis. The difference in 2D sheet doping concentrations (∆n = nLn-DNA−nControl) extracted in the Ln-DNA-doped MoS2 devices also showed positive values, which mean an increase in the number of electron carriers and consequently in n-doping of MoS2. The lowest ∆n was ~6 × 109 cm−2 in the case of Tb-DNA and the available n-doping range by Ln-DNA was between ~6 × 109 cm−2 and ~2.6 × 1010 cm−2, in which the device performance can be controlled. In addition, we confirmed the improvements in on-current through Ln-DNA doping in Fig. 5c. The on-current ratio (=IOn_Ln-DNA/IOn_Control) was between approximately 8 and 10. This enhancement is thought to be caused by the reduction in effective electron barrier height through Ln-DNA doping, indicating that there was a reduction in contact resistance. Based on simple on-state contact resistance extraction45, Gd-DNA doping reduced the estimated contact resistance to ~72.2 kΩ (from ~90.7 kΩ) on the MoS2 device and increased it to 95.1 kΩ (from ~67.7 kΩ) on the WSe2 device. On the other hand, we observed a degradation in the electronic performance of WSe2 devices after Ln-DNA doping, as shown in Fig. 5d, which presents the ID − VG characteristics of undoped/doped WSe2 devices by Gd-DNA (at VDS = −5 V). Here, a negative shift in VTH (from 10 V to 8 V) and a decrease in on-current (from 5.2 × 10−5 A/μm to 9.2 × 10−8 A/μm) were confirmed, indicating the n-doping of WSe2. Then, ∆VTH values extracted in each Ln-DNA-doped WSe2 device were between −1.4 V and −3.1 V; we also obtained negative ∆p values (=pLn-DNA−pControl) in the range from −1.0 × 1010 cm−2 to −2.4 × 1010 cm−2 (Fig. 5e). These changes are consistent with the red-shift phenomenon in the Raman peaks mentioned above, which is indicative of n-doping (reduction of hole concentration in WSe2). In contrast to the improvement of on-current in MoS2 devices, Ln-DNA doping degraded the parameters of WSe2 devices, as shown in Fig. 5f. The on-current ratio was found to be below 0.3, likely because the energy band of WSe2 was shifted down after Ln-DNA doping. Consequently, its effective hole barrier height from the source to WSe2 was increased, resulting in an increase in contact resistance.

Electrical characterization of TMD transistors doped by Ln-DNA.

ID − VG characteristics of the (a) MoS2 and (d) WSe2 transistors undoped/doped by Gd3+-DNA. Threshold voltage shifts (ΔVTH = VTH_Ln-DNA – VTH_Control) and variations of carrier concentration (Δn = n_Ln-DNA – n_Control and Δp = p_Ln-DNA – p_Control) extracted in (b) MoS2 and (e) WSe2 transistors, which were undoped/doped by Ln-DNA. On-current ratio (Ion ratio = Ion_Ln-DNA/Ion_Control) extracted in the undoped/doped (c) MoS2 and (f) WSe2 transistors.

However, as already expected, slightly different changes were observed on the TMD-based electronic devices after doping by the Co-DNA. Figure 6a shows the ID−VG characteristics of MoS2 devices undoped and doped by Co-DNA (Gd3++Cu2+), where a positive shift in VTH (from –30 V to –28.2 V) and a reduction in on-current (from 8.2 × 10−5 A/μm to 4.2 × 10−5 A/μm) were observed after the Gd3+-based Co-DNA doping, indicating a light p-doping of MoS2. Based on the extracted ∆VTH (=VTH_Co-DNA − VTH_Control) and ∆n (=nCo-DNA−nControl) values of MoS2 devices doped by various Co-DNA in Fig. 6b, Co-DNA seems to cause a light p-doping phenomenon on MoS2 where Eu3+ or Gd3+ ions were incorporated. Here, we observed positive ∆VTH values above 1.2 V and negative ∆n values below −9 × 109 cm−2. This p-doping concentration is slightly lower than those of the other TMD doping techniques using OTS (~1.6 × 1010 cm−2)38 or M-DNA (~2.3 × 1010 cm−2)39. Compared to the Eu- or Gd-DNA (Ln-DNA), the additionally inserted Cu2+ ions are expected to be successfully combined with the DNA base pairings and remaining backbone sites. This consequently provides very light p-doping of MoS2 because the strength of negative charges is reduced and the effective electron barrier height is increased by the up-shift of the MoS2 energy band. However, a light n-doping phenomenon (negative ∆VTH below −1.5 V and positive ∆n above 1010 cm−2) was interestingly observed in the MoS2 devices doped by Co-DNA with Tb3+ or Er3+ ions. This n-doping concentration is also lower than those of the other doping techniques using Cs2CO3 (~1 × 1011 cm−2)37 or pristine DNA (~6.4 × 1010 cm−2)39. Compared to the cases of Eu- or Gd-DNA (Ln-DNA), fewer Cu2+ ions are attached to the Tb- and Er-DNA, eventually allowing the polarity of the Co-DNA to remain negative. We also note that all of these changes in the MoS2 device performance coincide with the previously mentioned Raman peak shifting behavior for the various kinds of Ln ions. This difference (between n- and p-doping by Co-DNA) was clearly observed in the on-current ratio, which was plotted in Fig. 6c. As expected for the MoS2 devices p-doped by Co-DNA with Eu3+ or Gd3+ ions, the on-currents were reduced 0.06 ~ 0.2 times compared to the initial values of the control samples. However, in the cases where Tb3+ and Er3+ ions were used (n-doping), a 2.1 ~ 4-fold increase in the on-current was observed after Co-DNA doping.

Electrical characterization of TMD transistors doped by Co-DNA.

ID–VG characteristics of the (a) MoS2 and (d) WSe2 transistors undoped/doped by Gd3+-based Co-DNA. Threshold voltage shifts (ΔVTH = VTH_Ln-DNA – VTH_Control) and variations of carrier concentration (Δn = n_Ln-DNA – n_Control and Δp = p_Ln-DNA – p_Control) extracted in (b) MoS2 and (e) WSe2 transistors, which were undoped/doped by Co-DNA. On-current ratio (Ion ratio = Ion_Ln-DNA/Ion_Control) extracted in the undoped/doped (c) MoS2 and (f) WSe2 transistors.

A similar doping phenomenon by Co-DNA was observed on WSe2 films, as shown in Fig. 6d. The Gd3+-based Co-DNA caused p-doping on WSe2 as well as on MoS2 so that a positive shift in VTH and an increase in on-current were observed due to the up-shift in the WSe2 energy band by p-doping and the consequent reduction of the effective hole barrier height at the source-side Pt-WSe2 junction. Figure 6e shows the ∆VTH and ∆p extracted in the WSe2 devices doped by various Co-DNA, which also presents the difference between p- and n-doping effects. In the case of Eu3+- and Gd3+-based Co-DNA doping, we obtained positive ∆VTH (1.5 ~ 1.9 V) and ∆p (1.4 × 1010 ~ 1.9 × 1010 cm−2) values, which indicate p-doping of WSe2. The other Tb3+- and Er3+-based Co-DNA resulted in negative ∆VTH and ∆p values (n-doping of WSe2), which were, respectively, below −1.4 V and −1.1 × 1010 cm−2. As seen in Fig. 6f, the on-current ratio of the WSe2 devices before/after doping was also increased up to 4.1 when Eu3+- and Gd3+-based Co-DNA doping (p-doping) was performed. However, the on-current ratio was reduced below 0.25 in devices doped with Tb3+- and Er3+-based Co-DNA (n-doping). In additional experiments on tri-layer TMDs, we confirmed that the doping effects of Ln- or Co-DNA were independent of TMD thickness. We also note that the influence of four kinds of solvents used during the fabrication process (DI water, acetone, IPA and buffer solutions) on TMD-based devices (here, ΔVTH) seems to be negligible when compared to the effect of Ln- or Co-DNA-doping (0.3–0.33 V for DI water, 0.2–0.22 V for acetone, −0.24–−0.2 V for IPA and 0.17–0.23 V for the buffer solution). In addition, the VTH values of the Ln- and Co-DNA-doped MoS2 and WSe2 devices changed slightly after 120 hours of air-exposure (Supplementary information Fig. S7). The ∆VTH values of Ln-DNA-doped MoS2 and WSe2 transistors increased 15–20%, indicating the weakening of the n-type doping effects after 120 hours. The ∆VTH values of the Co-DNA-doped samples also decreased (Eu- or Gd-based Co-DNA) or increased (Tb- or Er-based Co-DNA) as a function of air exposure time because of the reduced dipole moment of the phosphate backbone (PO4−) and lanthanide ions (Ln3+) related to the humidity-associated structural deformation of Ln- and Co-DNA nanostructures46.

Characteristics of Co-DNA-doped TMD optoelectronic devices

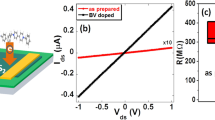

We then performed a photocurrent measurement on the Co-DNA-doped TMD photodetector devices with 655-nm, 785-nm and 850-nm lasers in order to investigate the effects of p- and n-doping by Co-DNA on optoelectronic device performance. Figure 7a shows a schematic diagram of the Co-DNA-doped TMD photodetector, along with the corresponding energy band diagrams of i) MoS2 and ii) WSe2 before/after Co-DNA doping. Compared to the control device, the depletion width at the source/MoS2 junction is expected to be broadened after Eu3+ or Gd3+-based Co-DNA doping (pink solid line: p-doping), consequently helping to collect photocarriers and increase photocurrent. However, the n-doping phenomenon by Tb3+ or Er3+-based Co-DNA is predicted to narrow the depletion width and reduce photocurrent below that of the control device (green dotted line: n-doping). In contrast, WSe2 photodetectors doped by the Tb3+ or Er3+-based Co-DNA show higher photocarrier collection and subsequently higher photocurrent. Figure 7b shows ID − VG characteristics of a Gd3+-based Co-DNA-doped TMD photodetector before and after light exposure. In the off-state (VGS < VTH), the absence of majority carrier paths in MoS2 (low electron current) and the high hole barrier height (low hole current) are expected to reduce the dark current below a level of 10−11 A/μm. As a result, the photocurrent was more clearly observed in the off-state because of the low dark current level. We then extracted and plotted photoresponsivity (R = IPhoto/PLight) and detectivity (D* = (RA1/2)/(2eIDark)1/2) values as a function of VGS − VTH in Fig. 7c,d. Here, the generated photocurrent is ILaser_on−ILaser_off, PLight is the total incident optical power, A is the effective area of the device, e is the absolute value of the electron charge (1.6 × 10−19 C) and IDark is dark current. In Fig. 7c, Eu3+ or Gd3+-based Co-DNA-doped MoS2 devices showed higher photoresponsivity (~68 μA/W at VGS = VTH) than those (~25 μA/W at VGS = VTH) of Tb3+ or Er3+-based Co-DNA samples because of their broader depletion width and subsequent higher photocurrent. The photoresponsivity was increased as a function of VGS in all cases of Co-DNA because the conductivity of the electron channel is improved as VGS approaches VTH. An opposite trend was observed in detectivity (D*) because D* is expressed as the ratio of IPhoto to IDark and is also affected by the IDark, as shown in Fig. 7d. The highest value (maximum D* = ~6.02 × 104 Jones at VGS − VTH = −2.6 V) was obtained in the Eu3+-based Co-DNA-doped device. Figure 7e shows ID − VG characteristics of the WSe2 device doped by Gd3+-based Co-DNA before/after light exposure and we also extracted photoresponsivity and detectivity as a function of VGS − VTH in Fig. 7f,g. An opposite trend was observed in photoresponsivity of WSe2 devices compared to MoS2 devices; that is, higher values were obtained in the n-doped devices by Tb3+- and Er3+-based Co-DNA. In the Er3+-based Co-DNA-doped device, a maximum photoresponsivity of ~27 μA/W was observed at VGS = VTH. In addition, like the MoS2 photodetectors, the photoresponsivity of WSe2 devices increased as the VGS moved to the VTH point. Detectivity was also better in the n-doped WSe2 devices and it increased as a function of VGS − VTH, where the maximum detectivity of ~6.5 × 104 Jones was obtained in the Er3+-based Co-DNA-doped device when VGS − VTH = 3 V (~8.2 × 104 Jones at VGS − VTH = 5.2 V).

Schematic diagram and characterization of TMD photodetectors doped by various Co-DNA.

(a) Schematic diagram of Co-DNA-doped MoS2/WSe2 photodetectors with a light source (λ = 785 nm and P = 0.6 mW) and the energy band diagrams of Ti-MoS2/Pt-WSe2 junctions under the illuminated condition. ID-VG characteristics of Gd3+-based Co-DNA-doped (b) MoS2 and (e) WSe2 photodetectors before/after the laser exposure. Photoresponsivity of (c) MoS2 and (f) WSe2 photodetectors as a function of VGS–VTH (in off-state). Detectivity of (d) MoS2 and (g) WSe2 photodetectors as a function of VGS–VTH (in off-state).

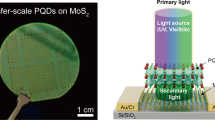

Then, the MoS2 and WSe2 photodetectors doped by Gd3+-based Co-DNA were investigated under laser exposure with different wavelengths (655-nm, 785-nm and 850-nm), as shown in Fig. 8. Figure 8a shows ID − VG characteristics of the TMD photodetectors measured before and after the various light exposures. In both devices an increase in photocurrent was observed as the laser wavelength decreased. The energy of incident light increases with decreasing wavelength and it eventually overcomes the direct bandgap (at K valley) at λ = ~655 nm (1.89 eV > 1.85 eV of direct Eg_MoS2 and 1.65 eV of direct Eg_WSe2), finally improving the absorption probability as seen in Fig. 8b. The photoresponsivity and detectivity ratio values (R = RCo-DNA/RControl and D* = D*Co-DNA/D*Control), which were extracted from the ID − VG curves of the devices doped by Gd3+ and Tb3+-based Co-DNA, were then plotted as a function of wavelength in Fig. 8c,d, respectively. As already mentioned in Fig. 7, p-doping of MoS2 by Gd3+-based Co-DNA and n-doping of WSe2 by Tb3+-based Co-DNA presented better optoelectronic performance (higher photoresponsivity and detectivity) at 785-nm and 850-nm as compared to the control devices. After doping the MoS2 and WSe2 devices respectively with Tb3+ and Gd3+-based Co-DNA, worse performance was observed in the same wavelength range because of the narrowed depletion width. However, under exposure to a 655-nm laser, dramatic performance improvement was observed in the devices doped by Tb3+-based Co-DNA, but not in the case of Gd3+-based Co-DNA. This seems to be attributed to the excellent emission and absorption properties of Tb3+-based Co-DNA around 655-nm, which were confirmed by PL analysis in Fig. 8e. Because of the Tb3+ ions attached mainly on the backbone sites, much higher PL intensity was observed in the Co-DNA, where a broad PL spectrum consists of various PL peaks between 438-nm and 630-nm; their corresponding energy state levels are shown in Fig. 8f. Several research groups previously reported the superior emitting properties of Tb3+ ions in the range from 380-nm to 700-nm47,48,49. Through the energy state levels of Tb3+ ions, the incident 655-nm light is expected to additionally generate electron-hole pairs in the Co-DNA region. After that, we predict that the photocarriers are transferred from the Co-DNA to the TMD layers, consequently increasing the number of total photocarriers and the photocurrent. We also note that Gd3+ ions generally show emitting and absorbing properties in the wavelength range between 250-nm and 312-nm, which is far from the wavelengths of the lasers used49,50,51.

Characterization of Co-DNA-doped TMD photodetectors under laser exposure with different wavelengths.

(a) ID−VG characteristics of MoS2 and WSe2 photodetectors doped by Gd3+-based Co-DNA under laser exposure with different wavelengths (655, 785 and 850 nm). (b) Energy band structures of bulk MoS2 and WSe2. Here, we approximately marked the photon or phonon transition under the laser exposure with different wavelengths. (c) Photoresponsivity ratio (RCo-DNA/RControl) and (d) detectivity ratio (D*Co-DNA/D*Control) of Gd3+ and Tb3+-based Co-DNA-doped TMD photodetector under different laser exposures. (e) Photoluminescence data of DNA and Tb3+-DNA crystals and Gaussian fitting lines for Tb3+-DNA PL data. Here, the excitation wavelength is 400 nm. (f) Energy state levels of Tb3+-DNA and the schematic presenting the mechanism of photocarrier transfer from Tb3+ ions to the TMD.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we proposed a new DNA-based doping method on the MoS2 and WSe2 films (representative n- and p-channel materials, respectively), which enabled ultra-low n- and p-doping control by selecting and/or combining different types of positive ions on DNA nanostructures. Because the PO4− in DNA caused n-doping on the TMD films by attracting and holding hole carriers on the side of the TMD, the various selections and/or combinations of the divalent and trivalent positive ions on DNA made it possible to achieve both very low-level n- and p-doping, which are very close to the intrinsic level. The available n-doping range (∆n) on the MoS2 by Ln-DNA was between 6 × 109 cm−2 and 2.6 × 1010 cm−2, which was even lower than that by pristine DNA (~6.4 × 1010 cm−2). The p-doping change (∆p) on the WSe2 by Ln-DNA was controlled from −1.0 × 1010 cm−2 to −2.4 × 109 cm−2. These changes were consistent with the red-shift phenomenon in Raman peaks, which indicated n-doping (an increase of electron carriers in MoS2 and a decrease of hole carriers in WSe2). In the case of Co-DNA doping, where Eu3+ or Gd3+ ions were incorporated, a light p-doping phenomenon was observed on the MoS2 and WSe2 (respectively, negative ∆n below −9 × 109 cm−2 and positive ∆p above 1.4 × 1010 cm−2) because the additionally inserted Cu2+ ions probably reduced the strength of negative charges in Ln-DNA. However, a light n-doping phenomenon (positive ∆n above 1010 cm−2 and negative ∆p below −1.1 × 1010 cm−2) was interestingly observed in the MoS2 and WSe2 devices doped by Co-DNA with Tb3+ or Er3+ ions. Compared to the cases of Eu- or Gd-DNA (Ln-DNA), fewer Cu2+ ions are thought to be additionally attached to the Tb- and Er-DNA (Ln-DNA), eventually maintaining a negative polarity of Co-DNA. We also found a significant increase in on-current in the MoS2 and WSe2 devices (by a factor of ~4), which were respectively doped with Tb3+-based Co-DNA (n-doping) and Gd3+-based Co-DNA (p-doping), due to the reduction of effective electron and hole barrier heights. In terms of optoelectronic device performance (photoresponsivity and detectivity), n-doping by Tb3+ or Er3+-based Co-DNA and p-doping by the Eu3+ or Gd3+-based Co-DNA improved MoS2 and WSe2 photodetectors, respectively. It is thought that the depletion width at the source/TMD junction is broadened after proper Co-DNA doping, consequently helping in collecting photocarriers and increasing photocurrent. In particular, we also found an interesting effect of Tb3+ ions on the TMD photodetectors; the Tb3+ ions in the Co-DNA region absorbed incident 655-nm light well, generated electron-hole pairs, transferred the carriers to the TMD layers and finally increased the number of photocarriers and the photocurrents. Ultra-low doping research using amalgamative materials is expected to play a significant role in the improvement of TMD device performance in the short term and in the continued development of the bio-electronic research field in the long term.

Experimetal Methods

DNA DX lattice fabrication

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-purified synthetic oligonucleotides of DNA was purchased from BIONEER (www.bioneer.com). Two DX tiles were used to construct a 2D DNA nanostructure through a conventional free solution annealing process. Complexes for the DX structure (200 nM) were formed by mixing a stoichiometric quantity of each strand in physiological 1 × TAE/Mg2+ buffer (40 mM Tris base, 20 mM acetic acid, 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) and 12.5 mM magnesium acetate). They were slowly cooled from 95 °C to 25 °C to facilitate hybridization by placing micro-tubes in 2 L of boiled water in a Styrofoam box for at least 24 hours.

Lanthanide ion coordination on DNA

For the Ln-ion doping, the individual DNA strands in a total volume of 250 μL were mixed with different concentrations (0, 0.5, 1 and 2 mM) of Er(NO3)3•5H2O, Eu(NO3)3•5H2O, Gd(NO3)3•6H2O and Tb(NO3)3•6H2O (purchased from Sigma-Aldrich). After annealing DX lattices in a test tube, the appropriate amount of Ln-ion solution was added and the mixture was then incubated at room temperature for 24 hours.

AFM measurement on DNA and Ln-DNA

AFM measurement was performed in a substrate assisted grown sample. A DNA-covered sample was attached to the metal puck using instant glue. 20 μL of 1 × TAE/Mg2+ buffer was added onto the substrate and 10 μL of 1 × TAE/Mg2+ buffer was mounted onto the AFM tip [A NP-S oxide-sharpened silicon nitride tip (Veeco, USA)]. AFM images were obtained by a Digital Instruments Nanoscope III (Veeco, USA).

Characterizations of Ln-DNA or Co-DNA-doped TMD films

Ln-DNA or Co-DNA-doped TMD samples were investigated and compared with a control sample (undoped TMD) by PL/Raman spectroscopy (Alpha300 M+, WITec). Here, TMD bulk flakes with similar thickness (~38 nm for MoS2 and ~33 nm for WSe2) were selected through AFM analysis in order to avoid the thickness effect. Raman spectroscopy with an excitation wavelength of 532 nm was used; the laser beam size was approximately 0.7 ~ 0.9 μm and the instrumental spectral resolution was less than 0.9 cm−1. An integration time of 5 seconds and a spectrometer with 1800 grooves/mm was employed for the test.

Fabrication of Ln-DNA or Co-DNA-doped TMD electronic/optoelectronic devices

For the fabrication of back-gated TMD transistors, source/drain electrode regions were patterned (channel length and width are 5 μm) on TMD/SiO2/Si samples by optical lithography, followed by 10-nm-thick Ti (for MoS2) or Pt (for WSe2) and 50-nm-thick Au deposition in an e-beam evaporator. After fabrication of TMD devices, ~150 μL volume of pristine DNA, Ln-DNA, or Co-DNA sample solution was dropped onto TMD devices in order to fully cover the TMD surface. After drop-casting the sample on TMD, we incubated the samples in a natural drying environment at room temperature for about 10 hours. We performed this same drop-casting and natural drying process for each TMD transistor five times to ensure full coverage of DNA on the TMD flakes. After finishing this process, TMDs were washed with DI water. Transistors were doped by Ln-DNA or Co-DNA with different metal ions (Eu3+, Gd3+, Tb3+, Er3+, or Cu2+). Here, the thickness of the gate oxide (SiO2) was 90 nm.

Electrical characterization of Ln-DNA or Co-DNA-doped TMD electronic devices

The fabricated transistor devices were electrically analyzed using an HP 4415B semiconductor parameter analyzer (ID − VD and ID − VG). The threshold voltage (VTH) and carrier concentration (n) were calculated from ID − VG data. All drain currents (ID) were normalized according to the channel width (W). For the calculation, we used the equation n (or p) = IDL/qWμVD, where q is the electron charge and L/W is the ratio of length to width of the channel. For comparison with other doping studies performed on different numbers of layers of TMD films, the extracted 2D carrier concentration values were also normalized by the number of TMD layers.

Optical characterization of Ln-DNA- or Co-DNA-doped

In order to investigate the optoelectronic properties of the fabricated Ln-DNA- or Co-DNA-doped TMD devices, a current-voltage (ID − VG) measurement was performed under both dark and illuminated conditions. The light source was a dot laser with wavelengths of 655 nm, 785 nm and 850 nm and an optical power of 0.6 mW. For the characterization and comparison of the TMD optoelectronic devices doped by Ln-DNA or Co-DNA with different metal ions (Eu3+, Gd3+, Tb3+, Er3+ or Cu2+), photo-responsivity (R) and detectivity (D*) were calculated from ID − VG curves. R is IPhoto/PLight and D* is (RA1/2)/(2eIDark)1/2, where IPhoto is the generated photo-current, PLight is the total incident optical power, A is the effective area of the detector, e is the absolute value of electron charge (1.6 × 10−19 C) and IDark is the dark current.

Photoluminescence measurement of pristine and Tb3+-doped DNA

The emission spectra of pristine DNA and Tb3+-DNA on silica substrate were obtained using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (LS-55, PerkinElmer Instruments, USA) at room temperature. The emission spectrum was measured by exciting the sample at wavelength of 400 nm.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Kang, D.-H. et al. Ultra-low Doping on Two-Dimensional Transition Metal Dichalcogenides using DNA Nanostructure Doped by a Combination of Lanthanide and Metal Ions. Sci. Rep. 6, 20333; doi: 10.1038/srep20333 (2016).

References

Seeman, N. C., Nanomaterials based on DNA. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79, 65–87 (2010).

Yin, P. et al. Programming DNA tube circumferences. Science 321, 824–826 (2008).

Winfree, E., Liu, F., Wenzler, L. A. & Seeman, N. C. Design and self-assembly of two-dimensional DNA crystals. Nature 394, 539–544 (1998).

He, Y. et al. Hierarchical self-assembly of DNA into symmetric supramolecular polyhedral. Nature 452, 198–201 (2008).

Rothermund, P. W. K. Folding DNA to create nanoscale shapes and patterns. Nature 440, 297–302 (2006).

Rikken, G. A new twist on spintronics. Science 331, 864–865 (2011).

Bader, S. D. & Parkin, S. S. P. Spintronics. Cond. Mat. Phys. 1, 71–88 (2010).

Braun, E., Eichen, Y., Sivan, U. & Ben-Yoseph, G. DNA-templated assembly and electrode attachment of a conducting silver wire. Nature 391, 775–778 (1998).

Rakitin, A. et al. Metallic conduction through engineered DNA: DNA nanoelectronic building blocks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 3670–3673 (2011).

Nam, J.-M., Thaxton, C. S. & Mirkin, C. A. Nanoparticle-based bio-bar codes for the ultrasensitive detection of proteins. Science 301, 1884–1886 (2003).

Lu, T., Goldsmith, B. R., Kybert, N. J. & Johnson. A. T. C. DNA-decorated graphene chemical sensors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 083107 (2010).

Lewis, F. D. DNA molecular photonics. Photochem. Photobiol. 81, 65–72 (2005).

Seeman, N. C. DNA in a material world. Nature 421, 427–431 (2003).

Sharma, J. et al. Control of self-assembly of DNA tubules through integration of gold nanoparticles. Science 323, 112–116 (2009).

Pal, S., Deng, S., Ding, B., Yan, H. & Liu, Y. DNA-Origami-directed self-assembly of discrete silver-nanoparticle architectures. Angew. Chem. Int. Edn. Engl. 49, 2700–2704 (2010).

Rinker, S., Ke, Y., Chhabra, R. & Yan, H. Self-assembled DNA nanostructures for distance-dependent multivalent ligand–protein binding. Nat. Nanotechnol. 3, 418–422 (2008).

Yan, H., Park, S. H., Finkelstein, G., Reif, J. H. & LaBean, T. H. DNA-templated self-assembly of protein arrays and highly conductive nanowires. Science 301, 1882–1884 (2003).

Tanaka, K., Tegeiji, A., Kato, T., Toyama, T. & Shionoya. M. A discrete self-assembled metal array in artificial DNA. Science 299, 1212–1213 (2003).

Duguid, J., Bloomfield, V. A., Benevides, J. & Thomas, G. J. Raman spectroscopy of DNA-metal complexes. 1. interactions and conformational effects of the divalent-cation-Mg, Ca, Sr, Ba, Mn, Co, Ni, Cu, Pd and Cd. Biophys. J. 65, 1916–1928 (1993).

Switzer, C., Sinha, S., Kim, P. H. & Heuberger, B. D. A purine-like Ni2+ base pair for DNA. Angew. Chem. Int. Edn. Engl. 44, 1529–1532 (2005).

Lee, J. S., Latimer, L. J. P. & Reid, R. S. A cooperative conformational change in duplex DNA Induced by Zn2+ and other divalent metal ions. Biochem. Cell Biol. 71, 162–168 (1993).

Keren, K., Berman, R. S., Buchstab, E., Sivan, U. & Braun, E. DNA-templated carbon nanotube field-effect transistor. Science 302, 1380–1382 (2003).

Maune, H. T. et al. self-assembly of carbon nanotubes into two-dimensional geometries using DNA Origami templates. Nat. Nanotechnol. 5, 61–66 (2010).

Radisavljevic, B., Radenovic, A., Brivio, J., Giacometti, V. & Kis, A. Single-layer MoS2 transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 6, 147–150 (2011).

Liu, W. et al. Role of metal contacts in designing high-performance monolayer n-type WSe2 field effect transisstors. Nano Lett. 13, 1983–1990 (2013).

Bertolazzi, S., Brivio, J. & Kis, A. Stretching and breaking of ultrathin MoS2 . ACS Nano 5, 9703–9709 (2011).

Pu, J., Li, L. J. & Takenobu, T. Flexible and Stretchable Thin-film transistors based on molybdenum disulphide. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 14996–15006 (2014).

Mak, K. F., Lee, C., Hone, J., Shan, J. & Heinz, T. F. Atomically thin MoS2: a new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 136805 (2010).

Yin, Z. et al. Single-layer MoS2 phototransistors. ACS Nano 6, 74–80 (2012).

Lopez-Sanchez, O., Lembke, D., Kayci, M., Radenovic, A. & Kis, A., Single-layer MoS2 photodetector. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 497–501 (2013).

Mak, K. F. et al. Tightly bounded trions in monolayer MoS2 . Nat. Mater. 12, 207–211 (2013).

Fang, H. et al. Degenerate n-doping of few-layer transition metal dichalcogenides by potassium. Nano Lett. 13, 1991–1995 (2013).

Sreeprasad, T. S., Nguyen, P., Kim, N. & Berry, V. Controlled, defect-guided, metal-nanoparticle incorporation onto MoS2 via chemical and microwave routes: electrical, thermal and structural properties. Nano Lett. 13, 4434–4441 (2013).

Du, Y., Liu, H., Neal, A. T., Si, M. & Ye, P. D. Molecular doping of multilayer MoS2 field-effect transistors: reduction in sheet and contact resistances. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 34, 1328–1330 (2013).

Li, Y., Xu, C.-Y., Hu, P. A. & Zhen, L. Carrier control of MoS2 nanoflakes by functional self-assembled monolayers. ACS Nano 7, 7795–7804 (2013).

Chen, M. Stable few-layer MoS2 rectifying diodes formed by plasma-assisted doping. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 142110 (2013).

Lin, J. D. et al. Electron-doping-enhanced trion formation in monolayer molybdenum disulfide functionalized with cesium carbonate. ACS Nano 8, 5323–5329 (2014).

Kang, D.-H. et al. Controllable nondegenerate p-type doping of tungsten diselenide by octadecyltrichlorosilane. ACS Nano 9, 1099–1107 (2015).

Park, H. Y. et al. n- and p-type doping phenomenon by artificial DNA and M-DNA on two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. ACS Nano 8, 11603–11613 (2014).

Dugasani, S. R. et al. A 2D DNA lattice as an ultra-sensitive detector for beta radiations. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 2974–2979 (2014).

Kulkarni, A. et al. A novel nanometric DNA thin film as a sensor for alpha radiation. Sci. Rep. 3, 2062 (2013).

Tegenfeldt, J. O. et al. The dynamics of genomic-length DNA molecules in 100-nm channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101, 10979–10983 (2004).

Yang, J. Y. et al. Improved growth behavior of atomic-layer-deposited high-k dielectrics on multilayer MoS2 by oxygen plasma pretreatment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 4739−4744 (2013).

Tonndorf, P. et al. Photoluminescence emission and Raman response of monolayer MoS2, MoSe2 and WSe2 . Opt. Express 21, 4908–4916 (2013).

Kim, S. et al. High-mobility and low-power thin-film transistors based on multilayer MoS2 crystals. Nat. Commun. 3, 1011 (2012).

Lee, J. et al. Structural and functional stabilities of artificially designed DNA ultra-thin films grown by silica assistance. Curr. Appl. Phys. 12, 1207–1211 (2012).

Tokida, Y. & Adachi, S. Photoluminescence properties and energy-level analysis of Ga2O3: Tb3+ green phosphor prepared by metal organic deposition. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 3, R100–R103 (2014).

Gai, Y. L. et al. Visible and NIR photoluminescence properties of a series of novel lanthanide–organic coordination polymers based on hydroxyquinoline–carboxylate ligands. Inorg. Chem. 51, 13128–13137 (2012).

Raju, G. S. R. et al. Gd3+ sensitization effect on the luminescence properties of Tb3+ activated calcium gadolinium oxyapatite nanophosphors. J. Electrochem. Soc. 158, J20–J26 (2011).

Li, Y.-C., Chang, Y.-H., Chang, Y.-S., Lin, Y.-J. & Laing, C.-H. Luminescence and energy transfer properties of Gd3+ and Tb3+ in LaAlGe2O7 . J. Phys. Chem. C 111, 10682–10688 (2007).

Zheng, K., Liu, Z., Lv, C. & Qin, W. Temperature sensor based on the UV upconversion luminescence of Gd3+ in Yb3+–Tm3+–Gd3+ co-doped NaLuF4 microcrystals. J. Mater. Chem. C 1, 5502–5507 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (No. 2015R1A2A2A01002965).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.-H.P. and S.H.P. initiated the project. D.-H.K., S.R.D. and H.-Y.P. contributed to the experimental design and device fabrication. D.-H.K., H.-Y.P., J.S. and Y.R. analyzed the data. B.G. carried out the atomic force microscopy. J.J. and S.L. performed the Raman spectroscopy. S.R.D. carried out the photoluminescence measurement. D.-H.K. carried out electrical and optical characterization. All authors participated in writing the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, DH., Dugasani, S., Park, HY. et al. Ultra-low Doping on Two-Dimensional Transition Metal Dichalcogenides using DNA Nanostructure Doped by a Combination of Lanthanide and Metal Ions. Sci Rep 6, 20333 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20333

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep20333

This article is cited by

-

DNA structures embedded with functionalized nanomaterials for biophysical applications

Journal of the Korean Physical Society (2021)

-

Luminophore Configuration and Concentration-Dependent Optoelectronic Characteristics of a Quantum Dot-Embedded DNA Hybrid Thin film

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

M-DNA/Transition Metal Dichalcogenide Hybrid Structure-based Bio-FET sensor with Ultra-high Sensitivity

Scientific Reports (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.