Abstract

Crystal violet lactone (CVL) is a classic halochromic dye which has been widely used as chromogenic reagent in thermochromic and piezochromic systems. In this work, a very first example of CVL-based reversible photochromic compound was developed, which showed distinct color change upon UV-visible light irradiation both in solution and in solid matrix. Moreover, metal complex of CVL salicylaldehyde hydrozone was facilely synthesized, exhibiting reversible photochromic properties with good fatigue resistance. It was served as promising solid material for photo-patterning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Photochromic materials have received considerable attention due to their diverse applications such as optical data storage1,2,3,4, photoelectric conversion5,6,7, multifunction photocontrollable switches8,9,10,11, photoresponsive smart surfaces12,13,14, molecular machines15,16, photoresponsive supramolecular self-assembly17,18 and photocontrollable biological processes19,20,21. Even though a few organic photochromic systems have been well demonstrated including azobenzene, spiropyran and diarylethenes22,23, the development of new photochromic system with excellent properties is still in great demand24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. Crystal violet lactone (CVL) is a classic triarylmethane (TMP) organic dye with many appealing attributes, such as long-wavelength absorption, high absorption coefficient, high chromaticity, excellent oil-solubility and low cost32. It is widely used as chromogenic reagent in the field of piezochromic and thermochromic materials (e.g. carbonless copy papers and thermal papers) due to its intrinsic halochromic property32,33. CVL was also reported to be an electrochromic material when it is combined with iron ion: Fe(III) is able to open the lactone of CVL in methanol but Fe(II) can’t34. Normally, excessive exposure to light will lead to an irreversible photodegradation for CVL35. So far there is however no report of using them as reversible direct photochromic materials. Achievement of photo-sensitive CVL derivatives will greatly expand its potential application areas.

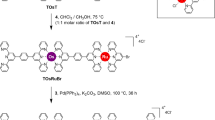

Previous reports have shown that spirolactone-containing dyes exhibited the potential in application of photochromic materials: well-controlled chemical modification of their molecular structures could result in a significant enhancement of photochromic properties, especially in the case of spirolactam formation1,36,37,38,39,40,41. In this work, specially designed crystal violet lactone salicylaldehyde hydrazone (3) was demonstrated. On one hand, the Schiff-base moiety in salicylaldehyde spirolactam hydrazone is a classic photochromic structure: upon light irradiation, there is a tautomerism from its enol-form to keto-form42. On the other hand, salicylaldehyde spirolactam hydrazone is a good chelation group for metal ions. The addition of certain metal ions will lead to a “spirolactam ring-open” reaction along with fluorescence or absorption spectra changes. Several small molecule probes for metal ions have been designed based on this structure43. Thus, by introducing salicylaldehyde spirolactam hydrazone to CVL structure (Fig. S1), the CVL derivative (3) may have a potential of photo-induced “spirolactam ring-open” properties. In this work, compound 3 was facilely synthesized by two-step synthesis44 with all inexpensive reagents. Complex 3-Zn was obtained by addition of Zn(II) to 3 in dichloromethane (DCM). Excess Zn(II) was used to ensure the efficient formation of the complex.

Results and Discussion

Complex 3-Zn was found to display reversible photochromism in DCM solution. As shown in Fig. 1a and Supplementary Information Video 1, the colorless solution turned blue upon 405 nm light irradiation (the power output of laser point is 20 mW). Moreover, all the conventional light sources even sunlight could induce that photochromic reaction. When light source was removed, the solution gradually restored to its original state. Before light irradiation, almost no absorption band above 450 nm was observed for 3-Zn. After light irradiation, a strong band centered at 605 nm with a shoulder peak around 567 nm emerged (Fig. 1a). The molar absorption coefficient of 3-Zn at 605 nm after light irradiation was as high as 5.5 × 104 cm-1mol-1L, which is similar to that of CVL45.

As shown in Fig. 2a, a possible mechanism was proposed to understand the color change of 3-Zn upon light irradiation. To confirm this assumption, CVL (1) was chosen as a control compound. It is well known that 1 is sensitive to pH: the leuco form (1(c), spirolactone ring close) turns to the colored form (1(o), spirolactone ring open) upon the addition of acid in DCM, along with a new absorption band centered at 603 nm32,33,34. The wavelength and shape of the absorption band for 3-Zn after light irradiation (3-Zn(o,k)) were consistent with those of 1(o) (Fig. 2b), indicating that 3-Zn underwent a spirolactam ring-open reaction to yield a ring-open product with blue color. As shown in Fig. S2, the binding ratio and binding constant are studied by UV-Vis spectra titration and Job’s plot method. The experimental results show that the binding ratio of 3-Zn is 1:1 and the binding constant is 6.9 × 106 L/mol.

(a) Proposed mechanism for color change of 3-Zn upon light irradiation (top).

The known tautomerism of 1 upon the addition of acid (middle) and 3 upon light irradiation (bottom). (b) Absorption spectra of 1 before (1(c)) and after (1(o)) the addition of 5 equiv HCl and absorption spectra of 3-Zn before (3-Zn(c,e)) and after (3-Zn(o,k)) light irradiation. (c) Absorption spectra of 3 before (3(e)) and after (3(k)) light irradiation and absorption spectra of 3 after light irradiation, then 10 equiv Zn(II) was added (3(k) with Zn(II)). (d) Infrared spectra of 3-Zn before (3-Zn(c,e)) and after (3-Zn(o,k)) light irradiation. Conditions: λ = 405 nm. For (b,c), [1] = 10 μmol/L, [3] = 10 μmol/L, [Zn(II)] = 100 μmol/L. For (d) DCM solution with 30% THF was used, [3] = 0.1 mol/L, [Zn(II)] = 1 mol/L.

According to the reports42,46, light irradiation promoted the tautomerism of salicylaldehyde hydrazone from its enol-form to keto-form. The absorption spectra of 3 showed an obvious decrease in absorbance at 333 nm after light irradiation, which was the result of the tautomerism from the enol-form (3(e)) to the keto-form (3(k)) (Fig. 2c, black line and red line). Meanwhile, no absorption band at 605 nm could be observed, indicating that the spirolactam in 3 was photostable without Zn(II). These results demonstrate that Zn(II) is an indispensable factor for the photochromism of 3-Zn. Interestingly, a characteristic absorption band centered at 605 nm emerged upon the addition of Zn(II) to the pre-exposed 3 (3(k)) (Fig. 2c, blue line), which further supported the existence of 3-Zn(o,k). In addition, more intuitive evidence was from the fluorescence spectra. 3-Zn exhibits strong fluorescence which is attributed to the chelation-enhanced fluorescence (CHEF) of salicylaldehyde hydrazone with Zn(II)47. After light irradiation, 3-Zn showed a weaker fluorescence than its precursor (Fig. S3). This fluorescence decrease was attributed to the formation of keto-form that can serve as a strong fluorescence quenching unit.

As shown in Table 1, the light source to promote photochromism of 3-Zn was at least within 325 nm to 450 nm. This range was fitted well with the absorption band of 3-Zn(c,e) (Fig. 1a). Normally, single benzene ring exhibited no absorption band above 300 nm, so the absorption band of 3-Zn(c,e) was mainly attributed to the absorbance of salicylaldehyde hydrazone Zn(II) complex moiety. These results further suggested that the salicylaldehyde hydrazone Zn(II) complex moiety was the light response group.

Furthermore, a more direct evidence for the tautomerism of 3-Zn from the enol-form to the keto-form was observed from the infrared spectra. As shown in Fig. 2d, 3-Zn(c,e) showed a broad absorption peak at 3389 cm-1 which is assigned as a stretching mode of the phenolic hydroxyl group. After light irradiation, the broad peak decreased and a new peak at 1585 cm−1 emerged which is assigned as a stretching mode of the new carbonyl group in 3-Zn(o,k).

According to the above experimental results, the mechanism of photochromism of 3-Zn should be as follows: light irradiation promoted the tautomerism of salicylaldehyde hydrazone moiety in the complex from its enol-form (3-Zn(c,e)) to keto-form (3-Zn(o,k)) and this change enhanced the chelation of Zn(II) and induced spirolactam ring-open reaction in 3-Zn to yield a blue-colored product (Fig. 2a).

To further testify the proposed mechanism, a control compound 4 containing a methoxy group instead of the phenolic hydroxyl group (Fig. 3 inset) was prepared and examined. As shown in Fig. 3, the changes of absorption spectra indicated that 4 was able to chelate Zn(II) to form 4-Zn. However, 4-Zn complex had no photochromic property upon light irradiation. These results prove that the tautomerism of phenolic hydroxyl group is an indispensable factor for the photochromism.

As shown in Fig. S4, different metal ions were used to replace Zn(II) in complex 3-Zn. The photochromic properties couldn’t be observed in most of the common metal ions except for Cd(II), which is in the same group of the periodic table with Zn(II) and usually induces a similar coordination property. However, since Cd(II) is highly toxic for organism, it is not suitable for the development of environment-friendly materials.

Moreover, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed on 3-Zn(c,e) and 3-Zn(o,k) with Gaussian 09 program to understand their electronic structure. B3LYP hybrid density function and the 6-31G (d,p) basis set were used to optimize the geometries. As shown in Fig. S5, LUMO energy level are distributed on the salicylaldehyde hydrazone Zn(II) complex moiety and HOMO energy level are distributed on the dimethylaminophenyl group for both 3-Zn(c,e) and 3-Zn(o,k). These results suggest that the salicylaldehyde hydrazone Zn(II) complex moiety is an active group in the photochromic reaction, supporting the proposed mechanism.

The response time and photostability depend on the intensity of the light source. As shown in Fig. 4a,b, the response time of 3-Zn is about 5 min upon the irradiation of a 6 W hand-held UV lamp at 365 nm. After being uninterrupted irradiated for 1 h, the absorption spectra of 3-Zn barely change, indicating a good stability of 3-Zn under common light source irradiation. When 3-Zn is irradiated by high-intensity light of a 500 W mercury lamp, the response time is less than 30 s (Fig. 4c,d). Excessive exposure to high-intensity light will lead to an irreversible photodegradation: the absorption band around 605 nm gradually disappear when the exposure time is longer than 30 s under a 500 W mercury lamp, while a strong band from 230 nm to 300 nm emerges. After being irradiated for 5 min, the absorption band around 605 nm almost disappears, indicating that 3-Zn has been degraded completely by light. The new absorption band from 230 nm to 300 nm was attributed to the small molecular degraded products.

The reversibility and fatigue resistance of 3-Zn are both important factors in its performance as potential photochromic materials. Since there is no absorption band around 605 nm for 3-Zn(c,e), the absorbance at 605 nm is proportional to the concentration of 3-Zn(o,k). As shown in Fig. S6, 10 μmol/L of light exposed 3-Zn turns to its leuco form in about 1 h at 25 °C. Moreover, the decay curve could be fitted well with first-order reaction kinetics (ln A = −kt), indicating that the transition from 3-Zn(o,k) to 3-Zn(c,e) is a first-order reaction (Fig. S6 inset). Therefore, the recovery rate is proportional to the concentration of 3-Zn(o,k). The thermal bleaching speed constant and half-life of 3-Zn(o,k) at room temperature are calculated to be 1.36 × 10−3 s−1 and 510 s, respectively, which is analogous to some photochromic naphthopyran compounds48. Besides the reversibility, the fatigue resistance of 3-Zn was also investigated. As shown in Fig. S7a, 3-Zn was toggled repeatedly between the leuco state and colored state for 10 times while the absorbance at 605 nm stayed constant without degradation.

3-Zn also displayed similar color and spectral changes in solid matrix such as silica gel (Fig. 1b). The fatigue resistance of 3-Zn on silica gel was as good as it in DCM (Fig. S7b). In silica gel, the light exposed product does not return exactly to the starting point, which might be due to the following reason: silica gel is acidic, in which the proton will lead to a side reaction for 3-Zn (Fig. S8)49,50,51. Fortunately, this flaw doesn’t impact the application of 3-Zn for solid photochromic material. As shown in Fig. 5 and Supplementary Information Video 2, pattern is successfully visualized with the highest resolution up to 0.5 mm, which indicate that 3-Zn could be served as promising solid material for photo-patterning.

Conclusions

In conclusion, a new TMP organic dye-based photochromic system has been developed for the first time. Crystal violet lactone salicylaldehyde hydrazone Zn(II) complex showed a distinct color change upon light irradiation in the UV-visible range. The mechanism studies showed that light irradiation promoted tautomerism of the phenolic hydroxyl group in salicylaldehyde hydrazone moiety from the enol-form to the keto-form and subsequently enhanced the chelation of Zn(II), inducing a spirolactam ring-open reaction to yield a blue-colored product. The photochromic reaction was reversible with good fatigue resistance. More importantly, the system exhibited photochromic property not only in solution but also in solid matrix, which makes it promising for photo-patterning applications. This work expands the spirolactone-containing dye photochromic family and will greatly further the advancement of CVL applications. Efforts on the development of more TMP-based photochromic system are in progress in our laboratories.

Methods

General

In these experiments, all the materials of analytical grade were used without further purification. Crystal violet lactone, hydrazine hydrate, salicylaldehyde, 2-methoxybenzaldehyde and zinc nitrate hexahydrate were purchased from J&K Chemical Co., Beijing, China. All the other materials were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Beijing Co., Beijing, China. Absorption spectra were measured by JASCO V-550 UV-Vis spectrophotometer, 1 cm and 0.2 quartz cells are used, respectively. UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectra were measured by Hitachi U-3010 UV-Vis spectrophotometer, BaSO4 was used as reference. Fluorescence spectra were determined on Hitachi F-4500 fluorescence spectrometer. Infrared spectra were performed on a Perkin-Elmer Frontier FT-IR/NIR spectrometer with a universal attenuated total reflection sampling accessory. NMR spectra were recorded by JOEL JNM-ECA400 spectrometer operated at 400 MHz and Bruker AVANCE III spectrometer operated at 600 MHz. ESI-MS spectra were obtained on SHIMADZU LCMS-IT-TOF LC-MS spectrometer without using the LC part. Laser of 325 nm was produced by Kimmon series He-Cd laser, laser of 375 nm was produced by CNI MDL-III-375 laser, laser of 405 nm was produced by LD-T405F00 laser pointer (power output 20 mW), laser of 450 nm laser was produced by CNI GLP-450 laser, laser of 532 nm was produced by FONLIN G-301 laser pointer. The photos and videos were carried with Canon EOS 600D camera.

Synthesis and characterization

The synthetic route to the target compounds is shown in Fig. S1. The compounds structures were verified by NMR and ESI-MS. The original data of NMR spectra and ESI-MS spectra were given in Supplementary Information.

Crystal violet lactone hydrazide (2)

To a 100 mL flask, crystal violet lactone (830 mg, 2 mmol) was dissolved in a mixed solvent of DCM (20 mL) and absolute ethanol (20 mL). After the addition of hydrazine hydrate (80%, 3 mL, excess), the stirred mixture was heated to 90 °C for 3 h. Then the solvent was concentrated to 10 mL under reduced pressure. After that, the solution was cooled to 4 °C to yield a white precipitate. The resulting precipitate was filtrated and washed with 30 mL absolute ethanol for three times. After dried under reduced pressure, 620 mg 2 (yield 73%) was obtained as white solid. ESI-MS spectrometry: m/z for [M+H]+, calculated: 430.2607, found: 430.2601. 1H NMR (DCCl3) δ (ppm): 2.91 (s, 12H), 2.99 (s, 6H), 4.82 (s, 1H), 6.62 (d, 4H, J = 8.7 Hz), 6.77 (m, 2H), 7.02 (d, 4H, J = 8.7 Hz), 7.08 (s, 1H), 7.41 (d, 1H, J = 2.3 Hz). 13C NMR (DCCl3) δ (ppm): 40.57, 40.68, 67.65, 110.84, 112.11, 115.47, 128.04, 128.83, 129.65, 130.78, 134.54, 149.52, 149.70, 166.11.

Salicylaldehyde crystal violet hydrazone (3)

To a 100 mL flask, 2 (429 mg, 2 mmol) and salicylaldehyde (305 mg, 2.5 mmol) were dissolved in a mixed solvent of DCM (20 mL) and absolute ethanol (20 mL). The stirred mixture was heated to 90 °C for 3 h. Then the solvent was concentrated to 10 mL under reduced pressure. After that, the solution was cooled to 4 °C to yield a yellow precipitate. The precipitate was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (petroleum ether/EtOAc, 3:1) to give 219 mg 3 (yield 41%) as a yellow solid. ESI-MS spectrometry: m/z for [M+H]+, calculated: 534.2869, found: 534.2864. 1H NMR (DCCl3) δ (ppm): 2.88 (s, 12H), 2.97 (s, 6H), 6.62 (d, 4H, J = 8.7 Hz), 6.85 (m, 2H), 7.13 (d, 4H, J = 8.7 Hz), 7.17 (m, 3H), 7.32 (d, 1H, J = 2.3 Hz), 9.81 (s, 1H), 10.83 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (DCCl3) δ (ppm): 40.47, 40.82, 75.72, 105.81, 112.12, 116.91, 117.90, 118.86, 119.24, 124.34, 128.38, 129.25, 130.36, 131.49, 131.81, 137.65, 149.96, 150.69, 155.91, 158.75, 166.08.

2-Methoxybenzaldehyde crystal violet hydrazone (4).

To a 100 mL flask, 2 (429 mg, 2 mmol) and 2-methoxybenzaldehyde (340 mg, 2.5 mmol) were dissolved in a mixed solvent of DCM (20 mL) and absolute ethanol (20 mL). The stirred mixture was heated to 90 °C for 3 h. Then the solvent was concentrated to 10 mL under reduced pressure. After that, the solution was cooled to 4 °C to yield a light green precipitate. The resulting precipitate was filtrated and washed with 30 mL absolute ethanol for three times. After dried under reduced pressure, 339 mg 4 (yield 62%) was obtained as light green solid. ESI-MS spectrometry: m/z for [M+H]+, calculated: 548.3026, found: 548.3016. 1H NMR (DCCl3) δ (ppm): 2.89 (s, 12H), 2.98 (s, 6H), 3.81 (s, 3H), 6.61 (d, 4H, J = 8.7 Hz), 6.85 (m, 3H), 7.18 (m, 5H), 7.26 (m, 1H), 7.84 (d, 1H, J = 6.0 Hz), 10.04 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (DCCl3) δ (ppm): 40.55, 40.86, 55.66, 75.62, 106.03, 111.05, 111.78, 117.35, 120.58, 124.48, 124.78, 126.21, 129.12, 129.65, 130.94, 131.15, 137.39, 147.48, 149.66, 150.58, 158.43, 165.87.

Preparation of photochromic system

1 mol/L Zn(NO3)2 stock solution was prepared in THF. 0.01 mol/L 3 or 4 stock solution was prepared in DCM. The photochromic system in solution was prepared by the addition of 10 equivalent Zn(II) to the solution of 3 in corresponding concentration. The photochromic system on silica gel was prepared as following: 10 g silica gel (200–300 mesh), 1 mL 1 mol/L Zn(NO3)2 stock solution and 10 mL 0.01 mol/L 3 stock solution were added to 30 mL DCM solution. After well mixed, DCM was evaporation under reduced pressure at room temperature. The products were obtained as light green powders.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Li, K. et al. Crystal Violet Lactone Salicylaldehyde Hydrazone Zn(II) Complex: a Reversible Photochromic Material both in Solution and in Solid Matrix. Sci. Rep. 5, 14467; doi: 10.1038/srep14467 (2015).

References

Schäfer, C. G. et al. Reversible Light-, Thermo-and Mechano-Responsive Elastomeric Polymer Opal Films. Chem. Mater. 25, 2309–2318 (2013).

Wu, Y. et al. Quantitative Photoswitching in Bis(dithiazole)ethene Enables Modulation of Light for Encoding Optical Signals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 2090–2094 (2014).

Yu, C. Y. Y. et al. A tetraphenylethene-based caged compound: synthesis, properties and applications. Chem. Commun. 50, 8134–8136 (2014).

Li, W. et al. Enantiospecific photoresponse of sterically hindered diarylethenes for chiroptical switches and photomemories. Scientific Reports 5, 9186 (2015).

Tsujioka, T. & Irie, M. Electrical functions of photochromic molecules. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 11, 1–14 (2010).

Kishida, M.-a., Kusamoto, T. & Nishihara, H. Photoelectric Signal Conversion by Combination of Electron-Transfer Chain Catalytic Isomerization and Photoisomerization on Benzodimethyldihydropyrenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 4809–4812 (2014).

Xie, X. & Bakker, E. Photoelectric Conversion Based on Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 7857–7860 (2014).

Ishii, N., Kato, T. & Abe, J. A real-time dynamic holographic material using a fast photochromic molecule. Scientific Reports 2, 819 (2012).

Boixel, J. et al. Second-Order NLO Switches from Molecules to Polymer Films Based on Photochromic Cyclometalated Platinum(II) Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 5367–5375 (2014).

Cui, X., Zhao, J., Zhou, Y., Ma, J. & Zhao, Y. Reversible Photoswitching of Triplet-Triplet Annihilation Upconversion Using Dithienylethene Photochromic Switches. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 9256–9259 (2014).

Goestl, R. & Hecht, S. Controlling Covalent Connection and Disconnection with Light. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 8784–8787 (2014).

Kitagawa, D., Nishi, H. & Kobatake, S. Photoinduced Twisting of a Photochromic Diarylethene Crystal. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 9320–9322 (2013).

Bushuyev, O. S., Corkery, T. C., Barrett, C. J. & Friscic, T. Photo-mechanical azobenzene cocrystals and in situ X-ray diffraction monitoring of their optically-induced crystal-to-crystal isomerisation. Chem. Sci. 5, 3158–3164 (2014).

Nachtigall, O., Kordel, C., Urner, L. H. & Haag, R. Photoresponsive switches at surfaces based on supramolecular functionalization with azobenzene-oligoglycerol conjugates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 9669–9673 (2014).

Marchi, E. et al. Photoswitchable Metal Coordinating Tweezers Operated by Light-Harvesting Dendrimers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 15277–15280 (2012).

Han, M. et al. Light-Triggered Guest Uptake and Release by a Photochromic Coordination Cage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 1319–1323 (2013).

Yagai, S. & Kitamura, A. Recent advances in photoresponsive supramolecular self-assemblies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 1520–1529 (2008).

Park, J., Sun, L.-B., Chen, Y.-P., Perry, Z. & Zhou, H.-C. Azobenzene-Functionalized Metal-Organic Polyhedra for the Optically Responsive Capture and Release of Guest Molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 5842–5846 (2014).

Szymański, W., Beierle, J. M., Kistemaker, H. A., Velema, W. A. & Feringa, B. L. Reversible Photocontrol of Biological Systems by the Incorporation of Molecular Photoswitches. Chem. Rev. 113, 6114–6178 (2013).

Chen, Z. et al. Light Controlled Reversible Inversion of Nanophosphor-Stabilized Pickering Emulsions for Biphasic Enantioselective Biocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 7498–7504 (2014).

Yamazoe, S., Liu, Q., McQuade, L. E., Deiters, A. & Chen, J. K. Sequential gene silencing using wavelength-selective caged morpholino oligonucleotides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 10114–10118 (2014).

Natali, M. & Giordani, S. Molecular switches as photocontrollable “smart” receptors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 4010–4029 (2012).

Zhang, J., Zou, Q. & Tian, H. Photochromic materials: more than meets the eye. Adv. Mater. 25, 378–399 (2013).

Rao, Y.-L., Amarne, H. & Wang, S. Photochromic four-coordinate N, C-chelate boron compounds. Coord. Chem. Rev. 256, 759–770 (2012).

Yang, Y., Hughes, R. P. & Aprahamian, I. Visible Light Switching of a BF2-Coordinated Azo Compound. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 15221–15224 (2012).

Iida, A., Saito, S., Sasamori, T. & Yamaguchi, S. Borylated Dibenzoborepin: Synthesis by Skeletal Rearrangement and Photochromism Based on Bora‐Nazarov Cyclization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 3760–3764 (2013).

Moorthy, J. N., Mandal, S., Mukhopadhyay, A. & Samanta, S. Helicity as a Steric Force: Stabilization and Helicity-Dependent Reversion of Colored o-Quinonoid Intermediates of Helical Chromenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 6872–6884 (2013).

Nakai, H. et al. Reversible Switching of the Luminescence of a Photoresponsive Gadolinium (III) Complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 8722–8725 (2013).

Helmy, S. et al. Photoswitching Using Visible Light: A New Class of Organic Photochromic Molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 8169–8172 (2014).

Rao, Y.-L., Hoerl, C., Braunschweig, H. & Wang, S. Reversible Photochemical and Thermal Isomerization of Azaboratabisnorcaradiene to Azaborabenzotropilidene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 9086–9089 (2014).

Yang, Y., Hughes, R. P. & Aprahamian, I. Near-Infrared Light Activated Azo-BF2 Switches. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 13190–13193 (2014).

Adams, C. S. inventor; The National Cash Register company, assignee. 3,3-bis(4-dimethylaminophenyl)6-dimethylaminophenyl phthalide. United States patent US 2,417,897. 1945 Jun 16.

Zhu, C. F. & Wu, A. B. Studies on the synthesis and thermochromic properties of crystal violet lactone and its reversible thermochromic complexes. Thermochim. Acta 425, 7–12 (2005).

Pinheiro, C., Parola, A. J., Laia, C. A. T., Camara, A. & Pina, F. Multiresponsive chromogenic systems operated by light and electrical inputs. New J. Chem. 33, 2144–2147 (2009).

Caine, M. A., McCabe, R. W., Wang, L. C., Brown, R. G. & Hepworth, J. D. The influence of singlet oxygen in the fading of carbonless copy paper primary dyes on clays. Dyes Pigm. 49, 135–143 (2001).

Knauer, K. H. & Gleiter, R. Photochromie von Rhodaminderivaten. Angew. Chem. 89, 116–117 (1977).

Fölling, J. et al. Photochromic rhodamines provide nanoscopy with optical sectioning. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 6266–6270 (2007).

Belov, V. N., Bossi, M. L., Fölling, J., Boyarskiy, V. P. & Hell, S. W. Rhodamine Spiroamides for Multicolor Single-Molecule Switching Fluorescent Nanoscopy. Chem. Eur. J. 15, 10762–10776 (2009).

Wu, L., Dai, Y. & Marriott, G. Optical Control of Calcium Affinity in a Spiroamido-rhodamine Based Calcium Chelator. Org. Lett. 13, 2018–2021 (2011).

Li, K., Xiang, Y., Tong, A. & Tang Ben, Z. Readily accessible rhodamine B-based photoresponsive material. Science China-Chemistry 57, 248–251 (2014).

Li, K. et al. Reversible Photochromic System Based on Rhodamine B Salicylaldehyde Hydrazone Metal Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 1643–1649 (2014).

Dürr, H. & Bouas-Laurent, H. Photochromism: Molecules and Systems. (Elsevier,: Amsterdam,, 2003 pp. 685).

Chen, X., Pradhan, T., Wang, F., Kim, J. S. & Yoon, J. Fluorescent chemosensors based on spiroring-opening of xanthenes and related derivatives. Chem. Rev. 112, 1910–1956 (2011).

Kuzuya, M. et al. Substituent Effects and Structural Limitations in the Conversion of 3, 3-Diarylphthalides to 4, 4-Diaryl-3, 4-dihydro-1 (2H)-phthalazinones. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 28, 3561–3569 (1980).

Eun-Mi, L., Seon-Yeong, G., Byung-Chul, J. & Sung-Hoon, K. K ass-controlled Hg2+transport from Crystal Violet Lactone to Fluoran. Dyes Pigm. 92, 1058–1061 (2012).

Hadjoudis, E. & Mavridis, I. M. Photochromism and thermochromism of Schiff bases in the solid state: structural aspects. Chem. Soc. Rev. 33, 579–588 (2004).

Wang, L., Qin, W., Tang, X., Dou, W. & Liu, W. Development and Applications of Fluorescent Indicators for Mg2+ and Zn2+. J. Phys. Chem. A 115, 1609–1616 (2011).

Song, L., Yang, Y., Zhang, Q., Tian, H. & Zhu, W. Synthesis and Photochromism of Naphthopyrans Bearing Naphthalimide Chromophore: Predominant Thermal Reversibility in Color-Fading and Fluorescence Switch. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 115, 14648–14658 (2011).

Bojinov, V. B., Venkova, A. I. & Georgiev, N. I. Synthesis and energy-transfer properties of fluorescence sensing bichromophoric system based on Rhodamine 6G and 1,8-naphthalimide. Sensors & Actuators B Chemical 143, 42–49 (2009).

Zhang, W. et al. A highly sensitive acidic pH fluorescent probe and its application to HepG cells. Analyst 134, 367–371 (2009).

Best, Q. A., Xu, R., Mccarroll, M. E., Wang, L. & Dyer, D. J. Design and investigation of a series of rhodamine-based fluorescent probes for optical measurements of pH. Org. Lett. 12, 3219–3221 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Science Foundation of Henan University of Technology (2015BS004), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21175079, 21375074 and 21371155), Research Found for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (20124101110002) and Scientific Research Foundation for Young Teacher of Zhengzhou University (51099075).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.L., Y.L., H.H. and A.T. designed the research. K.L., Y.L., J.T., L.L. and L.W. carried out the experiments. K.L., Y.L., J.T., H.H. and A.T. analysed data and participitated in the discussion. K.L., Y.L., H.H. and A.T. wrote and revised the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Li, K., Li, Y., Tao, J. et al. Crystal Violet Lactone Salicylaldehyde Hydrazone Zn(II) Complex: a Reversible Photochromic Material both in Solution and in Solid Matrix. Sci Rep 5, 14467 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep14467

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep14467

This article is cited by

-

Review on thermochromic materials: development, characterization, and applications

Journal of Coatings Technology and Research (2022)

-

AIE Ligand Constructed Zn(II) Complex with Reversible Photo-induced Color and Emission Changes

Chemical Research in Chinese Universities (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.