Abstract

We perform an in-depth study for mean first-passage time (MFPT)—a primary quantity for random walks with numerous applications—of maximal-entropy random walks (MERW) performed in complex networks. For MERW in a general network, we derive an explicit expression of MFPT in terms of the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the adjacency matrix associated with the network. For MERW in uncorrelated networks, we also provide a theoretical formula of MFPT at the mean-field level, based on which we further evaluate the dominant scalings of MFPT to different targets for MERW in uncorrelated scale-free networks and compare the results with those corresponding to traditional unbiased random walks (TURW). We show that the MFPT to a hub node is much lower for MERW than for TURW. However, when the destination is a node with the least degree or a uniformly chosen node, the MFPT is higher for MERW than for TURW. Since MFPT to a uniformly chosen node measures real efficiency of search in networks, our work provides insight into general searching process in complex networks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

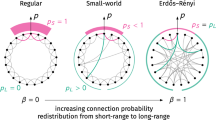

Random walks in complex networks have been heavily studied in the past years1,2,3 due to their wide range of applications in science and engineering4. Recently, continuously increasing efforts have been devoted to maximal-entropy random walks (MERW)5,6,7,8,9, also called Ruelle-Bowens random walks10,11, where all walking trajectories from given starting and ending points of a given length are equiprobable. In this sense, MERW is the most random of random walks, which maximizes the entropy rate12,13 and is in striking contrast with the traditional unbiased random walks (TURW) and other biased random walks. The unique diffusion process of MERW leads to several unusual phenomena, such as localization of stationary distribution5 and fast relaxation14.

As a powerful tool, MERW has been fruitfully applied in various fields. For instance, the localization phenomenon of stationary distribution for MERW makes it a good measure of centrality that is more discriminating than some classic centrality measures, e.g. PageRank, in the sense that it can distinguish evidently those nodes that PageRank regards as almost equally important15,16. Furthermore, since MERW incorporates both network structure and eigenvector centrality of nodes, it was also applied to establish a new algorithm of link prediction, which outperforms various supervised and unsupervised techniques of link prediction, on most test databases17. In addition, MERW has also found applications in optimal sampling algorithm18, demographic stability of population19, community detection20.

A fundamental quantity related to random walks is first-passage time (FPT)21,22,23,24, which is the expected time required for a random walker starting from a source point to a given target point. The mean first-passage time (MFPT) is defined as the average of FPTs over all source nodes in the network, which is a useful tool to analyze the behavior of random walks. The importance of MFPT originates from the essential role played by first encounter features appearing in various real situations, such as lighting harvesting25,26,27 and target search28,29. The MFPT can also serve as a significant indicator measuring node importance30 and efficiency of trapping process31. It is thus of utmost importance to study MFPT for different random-walk processes. Thus far, MFPT has been intensively studied for TURW32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40 and some biased random walks41,42,43,44, while related research about MFPT for MERW is still much less, although the particular diffusion process of MERW is suggested to significantly affect the leading behavior of MFPT.

In this paper, we propose a theoretical framework for MERW in complex networks and perform an in-depth study on the MFPT for MERW to a given target. We derive an explicit expression of FPT for MERW from one node to another in any connected network in terms of the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of adjacency matrix for the network. Based on the obtained representation for FPT, we further deduce an exact formula for MFPT to an arbitrary target node. Moreover, for uncorrelated networks, we also provide an analytical expression of MFPT for MERW at the mean-field level, using which we obtain the leading scalings of MFPT for uncorrelated scale-free networks with various degree exponent γ and show how the MFPT scales with the network size.

For MERW in uncorrelated scale-free networks, we study the MFPT for three representative cases with the target node being located at a hub node, a node with the smallest degree and a node uniformly chosen from the system, respectively. For all the three cases, we derive analytically the leading scalings for MFPT, all of which depend on the degree exponent γ that characterizes the heterogeneity extent of scale-free networks. Our results indicate that for the last two cases that the target is placed at a smallest degree node or a uniformly selected node, the leading scalings resemble each other, but both scalings are considerably larger than that corresponding to the first case when a hub is the target.

We also compare the obtained results of MFPT for uncorrelated scale-free networks with those corresponding to TURW. We show that when the target is fixed at a hub node, the MFPT for MERW is much less than that for TURW. On the contrary, when the target is placed at a smallest degree node or a randomly chosen node, the MFPT for MERW is larger than that associated with TURW. Therefore, in comparison with TURW, the special diffusion process of MERW has a stronger influence on the efficiency for searching a target in heterogeneous networks, making the process considerably more efficient for finding hub node but less efficient for locating a node with small degree or a randomly chosen node.

Results

Explicit expressions of MFPT for MERW

Throughout the paper, the random walk processes considered are defined in a connected undirected graph G with N nodes and E edges. The connectivity of nodes is described by the adjacency matrix A, in which the entry aij = 1 if nodes i and j are adjacent and aij = 0 otherwise. Then, the degree of a node i is  . Let

. Let  be the N eigenvalues of A, rearranged as

be the N eigenvalues of A, rearranged as  and let

and let  be their corresponding mutually orthogonal eigenvectors of unit length, where

be their corresponding mutually orthogonal eigenvectors of unit length, where  . Then, matrix A can be decomposed as the following spectral form:

. Then, matrix A can be decomposed as the following spectral form:

where  is an orthogonal matrix, obeying

is an orthogonal matrix, obeying

where I is the identity matrix.

Using above notations, we can introduce the MERW that is characterized by a unique stochastic matrix P, the ijth entry of which is given by

where λ1 is the principal eigenvalue of matrix A and μ1i is the ith entry of the principal eigenvector μ1 corresponding to λ1. This guarantees that MERW maximizes the entropy of a set of trajectories with a given length and end-points and leads to the maximal entropy rate of such processes5. The stationary distribution of MERW is11

The MERW is biased, which is different from TURW, where the transition probability pij = aij/ki from a node i to one of its neighboring nodes j is identical.

The main quantity we are interested in the paper is MFPT. Notice that MERW in an arbitrary connected binary network can be represented as generic random walk in a corresponding weighted network45. The ijth element of the generalized adjacency matrix (weight matrix) W for the weighted network is defined by wij = aijμ1iμ1j, which specifies the weight of the edge connecting nodes i and j. In this weighted network, the strength46 of a node i is given by  and the total strength of all nodes is

and the total strength of all nodes is  . For generic random walks in this weighted network, the transition probability is defined as

. For generic random walks in this weighted network, the transition probability is defined as

which is equal to transition probability, given by equation (3), for MERW in the original graph. The equivalence between the two random walks allows to determine the MFPT for MERW in a graph by evaluating the corresponding quantity for generic random walks in a related weighted network.

For MERW in a network, let Tij denote the FPT from node i to node j. Without loss of generality, let j be the target node and let Tj be the MFPT to node j. Then, by definition, the MFPT Tj is given by

Based on the equivalence between MERW and corresponding generic random walks, we derive an exact expression (see Methods) for Tij in terms of the eigenvalues and eigenvectors for adjacency matrix A:

Plugging equation (7) into equation (6), we arrive at an expression of MFPT Tj for MERW in a general graph with the deep trap fixed at an arbitrary node j, given by

Equation (8) provides a universal formula of MFPT to any node for MERW in an arbitrary network. Although it involves computing eigenvalues and eigenvectors of adjacency matrix, which puts heavy demands on time and computation resources for large networks, it can be utilized to check the results for MFPT obtained by other approaches, at least for small networks. Besides, equation (8) can also be used to compute the exact average 〈T〉 of Tj over all N targets:

which is exactly the MFPT when the target is uniformly distributed.

A drawback for equation (8) is that by using this spectral technique it seems very difficult, even impossible, to obtain the leading behavior of MFPT Tj characterizing the random-walk dynamic process. Thus, it is important to seek alternative techniques of evaluating MFPT Tj even for particular networks, which are not computationally demanding but are valid to estimate the scaling of MFPT. Fortunately, for uncorrelated networks, we can derive an expression of MFPT for MERW at the mean-field level, as well as its dominant scaling for scale-free networks. The details will be given below.

Theoretical prediction of MFPT for MERW in uncorrelated networks

We now consider the MFPT for MERW in uncorrelated networks, where the degree-degree correlations between adjacent nodes are absent. In a recent work47, we have shown that, for generic random walks in uncorrelated weighted networks, the MFPT to node j can be represented in terms of the strengths of the nodes as

Plugging  and s = λ1 into equation (10) gives the MFPT to node j for MERW:

and s = λ1 into equation (10) gives the MFPT to node j for MERW:

Thus, in order to obtain Tj, it is sufficient to determine μ1j. Although the evaluation of eigenvectors of a general matrix is very hard, for uncorrelated networks we can approximate  at the mean-field level (see Methods) as follows:

at the mean-field level (see Methods) as follows:

Substituting equation (12) into equation (11), we reach a theoretical approximation of MFPT for MERW to node j:

In Fig. 1, we report both the exact numerical results and theoretical approximate results of MFPT for MERW taking place in Erdös-Rényi (ER) network48 and Barabási-Albert (BA) network49, with both results being generated by equations (8) and (13), respectively. Figure 1 shows that the theoretical predictions agree well with the numerical results. From Fig. 1, we can also find that for nodes sharing identical degree, MFPT for MERW distributes in a broader range in BA network than in ER network. This difference lies in the structure of the networks. Since BA networks is heterogeneous, the component of leading eigenvector localizes at hub nodes and their neighbors5. For nodes having the same degree but different neighbors, their MFPT differ widely. For example, for two leaf nodes in treelike BA network that are linked to a hub node and a small-degree node farther from the hub, respectively, the MFPT to the leaf connected to a hub is much less than the MFPT to the other leaf. While for ER network, it is almost homogeneous, so the disparity for MFPT to different nodes with identical degree is relatively indiscernible.

MFPT to a given node for MERW in ER network (a) and BA network (b).

Black circles represent the numerical results obtained by equation (8) and each red triangle stands for the average of numerical values for Tj over all nodes having the same degree kj. Straight lines are the theoretical approximation generated according to equation (13).

In order to better understand the behavior of MFPT in inhomogeneous networks, in the sequel, grounded on the theoretical approximation in equation (13), we will analytically evaluate the leading scaling of MFPT for MERW in uncorrelated scale-free networks, aiming to unveil the effects of target location on the MFPT for MERW, as well as the difference between MERW and TURW in terms of the MFPT.

Leading scalings of MFPT for MERW in uncorrelated scale-free networks

Extensive empirical studies50 have shown that most real-world networks exhibit the striking scale-free property49, characterized by a power-law degree distribution P(k) ~ k−γ with γ > 2. In this section, we will study the leading scalings of MFPT for MERW in uncorrelated scale-free networks. We will examine the dominant scalings of MFPT for three representative target problems, with the target being a hub with the highest degree, a node with the lowest degree, or a node selected uniformly. Our goals are twofold. One is to uncover of the influence of target location or degree on the behavior of MFPT. The other is to find the scaling difference of MFPT between MERW and TURW.

Scaling of MFPT to a hub node

Let kmax denote the degree of a hub node and TH the MFPT to this hub node. Then, by equation (13),

The numerator in equation (14) can be evaluated as

Note that in a scale-free network with N nodes and power-law degree distribution P(k) ~ k−γ, the largest connectivity kmax can be estimated as51

Combining equations (14–16), we can obtain the leading scaling of TH:

Thus, the extent of inhomogeneity, characterized by the degree exponent γ, of scale-free networks strongly affects on the MFPT TH to a hub node for MERW. For 2 < γ < 3, TH is approximately equal to a constant; for γ = 3, TH grows logarithmically with the network size N; while for γ > 3, TH grows sublinearly with N.

We have checked our approximate results for TH against numerical values obtained according to equation (8) for uncorrelated scale-free networks with various values of γ, namely, γ = 2.5, γ = 3 and γ = 3.5. The considered network with γ = 3 is the BA model; while the networks with γ = 2.5 and γ = 3.5 are generalizations of the BA model52. The comparison for theoretical and numerical results is shown in Fig. 2, which indicates that for different values of γ and network size N, the analytical predictions from equation (17) agree with those numerical results given by equation (8). It should be mentioned that for γ = 2.5, the prediction is only valid for large networks, since in the process generating scale-free networks with 2 < γ < 3, multiple and self-connections are forbidden, which could introduce degree correlations in resultant networks53,54, leading to a deviation of numerical values from theoretical prediction.

MFPT to a hub node as a function of the network size N. The filled symbols are the data of numerical results.

The lines correspond to theoretical predictions provided by equations (17) or (20).

We next show that the behavior of MFPT for MERW in scale-free networks is quite different from that for TURW in the same networks. Similar to MFPT in weighted networks, the MFPT to a hub node for TURW in uncorrelated scale-free networks can be estimated by

where the numerator  can be approximated as

can be approximated as

Considering equation (16), the leading scaling of TH for TURW is

which scales sublinearly with the network size N but decreases with γ, a result consistent with that previously obtained55 using a different approach. In Fig. 2, we also plot the approximation for TH in equation (20) against their corresponding numerical values for TURW generated by the method in39, both of which agree well with each other.

Equations (17) and (20) show that the MFPT to a hub for MERW and TURW in uncorrelated scale-free networks display rich but distinct behavior. For both MERW and TURW, the MFPT depends on the exponent γ: lower γ corresponds to smaller MFPT. Moreover, in the whole range of γ, the MFPT for MERW is smaller than its counterpart for TURW. The root of the difference of MFPT between TURW and MERW is attributed to their local transition probabilities. For TURW, the transition probability pij from a node i to a neighboring node j is identical, while for MERW, the transition probability is pij = μ1j/(λ1μ1i) ≈ kj/(λ1ki), proportional to the degree of the neighboring node j. Thus, a walker visits a hub node more quickly in MERW than in TURW.

Scaling of MFPT to a node with the smallest degree

We now study the MFPT in uncorrelated scale-free networks when the target is a node with the smallest degree. According to equation (13), the MFPT to a smallest node can be represented as

where kmin denotes the degree of a node with the least degree. For sparse scale-free networks, their average node degree is a small constant50. Hence the minimal degree kmin can be regarded as a smaller constant. Then, recalling equations (15) and (16), the dominant scaling of TS can be approximated by

which is supported by extensive numerical simulations, see Fig. 3.

MFPT to the node with the least links.

The filled symbols stand for the numerical data, each being an average of MFPT over all nodes having the smallest degree; while the lines refer to the theoretical approximations provided by equations (22) or (23).

Equation (22) indicates that the MFPT TS for MERW in uncorrelated scale-free networks also exhibits rich behavior relying on the degree exponent γ. When 2 < γ < 3, TS varies superlinearly with the network size N; when γ = 3, TS scales with N as N ln N; when γ > 3, TS behaves linearly with N.

Although for both cases that the target is either at a hub node or at a smallest node, the MFPT is influenced by the degree parameter γ, the dependence relation of MFPT on γ is quite distinct, as can be seen from equations (17) and (22). Furthermore, in the whole range of 2 < γ < ∞, TH is much smaller than TS. As a result, for MERW in uncorrelated scale-free networks, generating all paths with identical probability is disadvantageous for the walker to explore nodes with small degree.

In addition, the MFPT TS for MERW is also different from that of TURW, where the MFPT TS to a node with the smallest degree can be estimated as

where equation (19) is used. This analytical solution is conformed by numerical results shown Fig. 3.

Equations (23) implies that for TURW, the MFPT TS scales linearly with network size N, independent of γ, which is totally different from the behavior of MFPT, provided by equation (22), corresponding to MERW. From equations (22) and (23), we can observe that for 2 < γ ≤ 3, the MFPT TS for MERW is larger than that for TURW; and that for γ > 3, although the leading scaling of MFPT TS grows linearly with network N for both MERW and TURW, the values of TS for MERW is greater than those corresponding to TURW, which can be seen from Fig. 3. Thus, for the case of target node located at a node with the smallest degree, performing MERW is substantially slowly to arrive at the destination than performing TURW, which is in stark contrast with the the case when the target node is a hub node, for which, performing MERW is more efficient than TURW to find the target. This phenomenon can also be accounted for by local transition probability from a node to one of its neighboring nodes with small degree, which is relatively smaller for MERW than for TURW.

Scaling of MFPT to a uniformly chosen node

The above studied MFPT to a particular target node in a network is often not looked upon as a general dynamical property of the network36,37. Instead, the average of MFPT over all targets reflects some global characteristics such as the efficiency of searching process. Thus, it is of significance to compute the target averaged MFPT. Next, we address random walks in an uncorrelated scale-free network with the target being a uniformly selected node in the network. In such situation, the MFPT 〈T〉 is defined as the average of FPTs over all pairs of nodes in the network, which involves a double average: The former is over all the source nodes to a given target node, the latter is the average of the first one. That is,

Next, we determine 〈T〉 for MERW and TURW, respectively.

For MERW, plugging equation (13) into equation (24) gives

where the term  can be estimated by

can be estimated by

Considering equations (15), (16) and (26), the quantity 〈T〉 follows

which is consistent with the numerical results, see Fig. 4.

MFPT to a target node uniformly selected from the whole network.

The filled symbols are the numerical results generated by equation (9); while the lines correspond to the theoretical predictions given by equations (27) or (30).

By comparing equation (22) and (27), we observe that for MERW the MFPT 〈T〉 exhibits similar behavior as that of TS. This phenomenon can be heuristically understood from the structure of scale-free networks, where the fraction of nodes with small degrees is very high. Moreover, the MFPT to a small-degree node is much larger than that of large-degree node. Thus, 〈T〉 and TS resemble in the leading behavior, which means that the dominant scaling of TS to a small-degree node is representative of MERW in scale-free networks.

We proceed to uncover the difference for 〈T〉 between MERW and TURW. For TURW, the quantity 〈T〉 can be approximated by

where the term  can be estimated as

can be estimated as

Recalling equation (19), we have

a scaling similar to that of TS for TURW. In Fig. 4, we plot the numerical results of 〈T〉 versus theoretical prediction in equation (30) for TURW in scale-free networks with different γ, which are consistent with each other.

On the other hand, for uncorrelated networks, the relation  holds. Then, according to inequality of arithmetic and geometric means, we can deduce a lower bound of 〈T〉 for uncorrelated networks:

holds. Then, according to inequality of arithmetic and geometric means, we can deduce a lower bound of 〈T〉 for uncorrelated networks:

which provides a minimal scaling for 〈T〉 in uncorrelated networks.

Equations (27) and (30) show that although the scaling of 〈T〉 for MERW and TURW behaves differently, the optimal linear scaling for 〈T〉 can be achieved both for TURW in scale-free networks with arbitrary 2 < γ < ∞ and for MERW in scale-free networks with γ > 3. In the end, we stress that although in the case of γ > 3, for both MERW and TURW, 〈T〉 can reach the minimal scaling, the cofactor of the dominating scaling for 〈T〉 is larger for MERW than for TURW, which can be seen in Fig. 4. Therefore, in the whole range of 2 < γ < ∞, the value of 〈T〉 is higher for MERW than that for TURW.

Discussion

In summary, we have presented a comprehensive and systematical analysis of MFPT for MERW in complex networks. We have provided an explicit expression of MFPT for MERW in a general network with a target node being located at an arbitrary node, which is provided in terms of eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the adjacency matrix for the network. Moreover, for MERW in an uncorrelated network, we have given an alternative theoretical prediction for MFPT at the mean-field level, which is devoid of calculating the eigenvalues and eigenvectors but gives good approximation for MFPT that are confirmed by extensive numerical results.

Applying the mean-field approximation formula, we have further addressed the leading behavior of MFPT for MERW in uncorrelated scale-free networks with a given target and various degree exponent γ, focusing on three representative cases with the target being a hub node, or a node with the least links, or a node chosen uniformly. For all the three cases, the MFPT is dependent on the degree of the target, as well as the degree exponent γ. We have also performed a comparison of the obtained results for MERW with those corresponding to TURW. For the case that the target is located at a hub node, a walker performing MERW arrives at the destination more quickly than performing TURW. However, for the two cases that target node is a node with the smallest degree or a node selected uniformly, MERW is less efficient for finding the target than for TURW.

We have also found that the values of MFPT for MERW in scale-free networks are distributed over a larger range than their counterparts for TURW. Thus, as an indicator of node importance, MFPT for MERW is better at discriminating influential nodes from common noncentral nodes. Finally, we note that our approximate analytical results only hold for uncorrelated networks. Since in real networks, there exist ubiquitous degree correlations among nodes50, it would be interesting to extend our methods to correlated networks in the future.

Methods

Expressing FPT for MERW in a network in terms of the spectra of its adjacency matrix

It has been reported56 that for generic random walks in a weighted network, the FPT Tij from node i to node j can be represented by the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the following matrix Γ defined as

where S is the diagonal strength matrix with its ith diagonal entry equal to the strength si of node i. It is evident that matrix Γ is real and similar to the transition matrix P and thus has the same set of eigenvalues as P. Let  be the N eigenvalues of matrix Γ for a network of size N, rearranged as

be the N eigenvalues of matrix Γ for a network of size N, rearranged as  and let

and let  denote the corresponding normalized and mutually orthogonal eigenvectors, where

denote the corresponding normalized and mutually orthogonal eigenvectors, where  . Then, the FPT for a walker starting from node i to first arrive at node j can be expressed as56

. Then, the FPT for a walker starting from node i to first arrive at node j can be expressed as56

For the particular weighted network associated with MERW, its weight matrix W satisfies

Inserting equation (34) into equation (32) leads to

which implies that the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the two matrices Γ and A, satisfy the following one-to-one relations:

and

Substituting equations (36) and (37) into equation (33) and considering  , we obtain

, we obtain

which provides a close-form expression of the FPT for MERW starting from an arbitrary node i to another node j.

Approximation of the principal eigenvector

Mean-field theory assumes that nodes having the same degree share the same structural properties57. Based on this hypothesis, we use μ(k) to denote the value of elements of principal eigenvector corresponding to nodes with degree k. By definition,

Applying the coarse-graining idea to degree classes58, equation (39) is equivalent to

where  . The entry

. The entry  of matrix

of matrix  defines the probability that two nodes of degree ki and kj are adjacent, namely

defines the probability that two nodes of degree ki and kj are adjacent, namely

where P(kj|ki) is the conditional probability59 that a node of degree ki is directly connected to a node with degree kj. Note that  can be also interpreted as a weight matrix of a weighted, fully connected graph, which is obtained by annealed network approach60. Since

can be also interpreted as a weight matrix of a weighted, fully connected graph, which is obtained by annealed network approach60. Since  is the eigenvector of

is the eigenvector of  corresponding to the principle eigenvalue λ1, we can approximate μ1 by

corresponding to the principle eigenvalue λ1, we can approximate μ1 by  . Next, we evaluate the principle eigenvector

. Next, we evaluate the principle eigenvector  of

of  .

.

Since in an uncorrelated network, the degrees of the two nodes connecting any edge are completely independent, the conditional probability can be estimated as

where 〈d〉 is the average node degree. Instituting equation (42) into equation (41) yields

which indicates that the matrix  can be represented as

can be represented as

where k is the degree sequence of the network and can be denoted by a vector as

For a matrix having the form αα⊤, where α is a nonzero vector, its rank is 1. Therefore, the rank of  is 1 and

is 1 and  has exactly one nonzero eigenvalue

has exactly one nonzero eigenvalue

Having obtained the principal eigenvalue λ, we continue to determine its corresponding eigenvector  . Obviously, λ and

. Obviously, λ and  satisfy the following relation:

satisfy the following relation:

which can be reexpressed as a system of equations:

where  is the ith entry of

is the ith entry of  . Therefore,

. Therefore,

Combining with normalized condition  , equation (49) can be solved to obtain

, equation (49) can be solved to obtain

Approximate μ1j by  leads to

leads to

References

Noh, J. D. & Rieger, H. Random walks on complex networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 118701 (2004).

Metzler, R. & Klafter, J. The restaurant at the end of the random walk: Recent developments in the description of anomalous transport by fractional dynamics. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 37, R161 (2004).

Burioni, R. & Cassi, D. Random walks on graphs: Ideas, techniques and results. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 38, R45 (2005).

Weiss, G. H. Aspects and Applications of the Random Walk (North Holland, Amsterdam, 1994).

Burda, Z., Duda, J., Luck, J. M. & Waclaw, B. Localization of the maximal entropy random walk. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 160602 (2009).

Burda, Z., Duda, J., Luck, J. M. & Waclaw, B. The various facets of random walk entropy. Acta Phys. Pol. B 41, 949–987 (2010).

Sinatra, R., Gómez-Gardeñes, J., Lambiotte, R., Nicosia, V. & Latora, V. Maximal-entropy random walks in complex networks with limited information. Phys. Rev. E 83, 030103 (2011).

Ochab, J. K. Maximal entropy random walk: Solvable cases of dynamics. Acta Phys. Pol. B 43, 1143–1155 (2012).

Frank, L. R. & Galinsky, V. L. Information pathways in a disordered lattice. Phys. Rev. E 89, 032142 (2014).

Ruelle, D. Thermodynamic formalism: the mathematical structure of equilibrium statistical mechanics (Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Parry, W. Intrinsic markov chains. Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. 112, 55 (1964).

Cover, T. M. & Thomas, J. A. Elements of Information Theory (Wiley, New York, 1991).

Gómez-Gardeñes, J. & Latora, V. Entropy rate of diffusion processes on complex networks. Phys. Rev. E 78, 065102 (2008).

Ochab, J. K. & Burda, Z. Exact solution for statics and dynamics of maximal-entropy random walks on Cayley trees. Phys. Rev. E 85, 021145 (2012).

Delvenne, J.-C. & Libert, A.-S. Centrality measures and thermodynamic formalism for complex networks. Phys. Rev. E 83, 046117 (2011).

Ochab, J. K. Maximal-entropy random walk unifies centrality measures. Phys. Rev. E 86, 066109 (2012).

Li, R. H., Yu, J. X. & Liu, J. Link prediction: the power of maximal entropy random walk. Proceedings of the 20th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management (CIKM) 1147–1156 (ACM, New York, 2011).

Hetherington, J. H. Observations on the statistical iteration of matrices. Phys. Rev. A 30, 2713 (1984).

Demetrius, L., Matthias Gundlach, V. & Ochs, G. Complexity and demographic stability in population models. Theor. Popul. Biol. 65, 211–225 (2004).

Ochab, J. K. & Burda, Z. Maximal entropy random walk in community detection. Eur. Phys. J. Special Topics 216, 73–81 (2013).

Redner, S. A Guide to First-Passage Processes (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2001).

Condamin, S., Bénichou, O. & Moreau, M. First-passage times for random walks in bounded domains. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 260601 (2005).

Condamin, S. & Bénichou, O. First-passage time distributions for subdiffusion in confined geometry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 250602 (2007).

Condamin, S., Bénichou, O., Tejedor, V., Voituriez, R. & Klafter, J. First-passage times in complex scale-invariant media. Nature 450, 77–80 (2007).

Bar-Haim, A., Klafter, J. & Kopelman, R. Dendrimers as controlled artificial energy antennae. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 6197–6198 (1997).

Bar-Haim, A. & Klafter, J. Geometric versus energetic competition in light harvesting by dendrimers. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 1662–1664 (1998).

Bentzm, J. L., Hosseini, F. N. & Kozak, J. J. Influence of geometry on light harvesting in dendrimeric systems. Chem. Phys. Lett. 370, 319–326 (2003).

Jasch, F. & Blumen, A. Target problem on small-world networks. Phys. Rev. E 63, 041108 (2001).

Bénichou, O., Loverdo, C., Moreau, M. & Voituriez, R. Intermittent search strategies. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 81 (2011).

White, S. & Smyth, P. Algorithms for estimating relative importance in networks. Proceedings of the Ninth ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD) 266–275 (ACM, New York, 2003).

Cantú, G. A. & Abad, E. Efficiency of trapping processes in regular and disordered networks. Phys. Rev. E 77, 031121 (2008).

Agliari, E. Exact mean first-passage time on the T-graph. Phys. Rev. E 77, 011128 (2008).

Kozak, J. J. & Balakrishnan, V. Analytic expression for the mean time to absorption for a random walker on the Sierpinski gasket. Phys. Rev. E 65, 021105 (2002).

Zhang, Z. Z., Qi, Y., Zhou, S. G., Xie, W. L. & Guan, J. H. Exact solution for mean first-passage time on a pseudofractal scale-free web. Phys. Rev. E 79, 021127 (2009).

Agliari, E. & Burioni, R. Random walks on deterministic scale-free networks: Exact results. Phys. Rev. E 80, 031125 (2009).

Tejedor, V., Bénichou, O. & Voituriez, R. Global mean first-passage times of random walks on complex networks. Phys. Rev. E 80, 065104 (2009).

Agliari, E., Burioni, R. & Manzotti, A. Effective target arrangement in a deterministic scalefree graph. Phys. Rev. E 82, 011118 (2010).

Meyer, B., Agliari, E., Bénichou, O. & Voituriez, R. Exact calculations of first-passage quantities on recursive networks. Phys. Rev. E 85, 026113 (2012).

Lin, Y., Julaiti, A. & Zhang, Z. Z. Mean first-passage time for random walks in general graphs with a deep trap. J. Chem. Phys. 137, 125104 (2012).

Hwang, S., Lee, D. S. & Kahng, B. First passage time for random walks in heterogeneous networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 088701 (2012).

Wu, B. & Zhang, Z. Z. Controlling the efficiency of trapping in treelike fractals. J. Chem. Phys. 139, 024106 (2013).

Yang, Y. H. & Zhang, Z. Z. Random walks in unweighted and weighted modular scale-free networks with a perfect trap. J. Chem. Phys. 139, 234106 (2013).

Fronczak, A. & Fronczak, P. Biased random walks in complex networks: The role of local navigation rules. Phys. Rev. E 80, 016107 (2009).

Bonaventura, M., Nicosia, V. & Latorax, V. Characteristic times of biased random walks on complex networks. Phys. Rev. E 89, 012803 (2014).

Lambiotte, R. et al. Flow graphs: Interweaving dynamics and structure. Phys. Rev. E 84, 017102 (2011).

Barrat, A., Barthélemy, M. & Vespignani, A. Weighted evolving networks: Coupling topology and weight dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 228701 (2004).

Lin, Y. & Zhang, Z. Z. Random walks in weighted networks with a perfect trap: An application of Laplacian spectra. Phys. Rev. E 87, 062140 (2013).

Erdös, P. & Rényi, A. On the evolution of random graphs. Publ. Math. Inst. Hung. Acad. Sci. 5, 17–60 (1960).

Barabási, A.-L. & Albert, R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science 286, 509–512 (1999).

Newman, M. E. J. The structure and function of complex networks. SIAM Rev. 45, 167 (2003).

Cohen, R., Erez, K., ben-Avraham, D. & Havlin, S. Resilience of the Internet to random breakdowns. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 4626 (2000).

Dorogovtsev, S. N., Mendes, J. F. F. & Samukhin, A. N. Structure of growing networks with preferential linking. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 4633 (2000).

Maslov, S. & Sneppen, K. Specificity and stability in topology of protein networks. Science 296, 910–913 (2002).

Park, J. & Newman, M. E. J. Why social networks are different from other types of networks. Phys. Rev. E 68, 026112 (2003).

Kittas, A., Carmi, S., Havlin, S. & Argyrakis, P. Trapping in complex networks. EPL 84, 40008 (2008).

Zhang, Z. Z., Shan, T. & Chen, G. R. Random walks on weighted networks. Phys. Rev. E 87, 012112 (2013).

Baronchelli, A. & Pastor-Satorras, R. Mean-field diffusive dynamics on weighted networks. Phys. Rev. E 82, 011111 (2010).

Boguñá, M., Castellano, C. & Pastor-Satorras, R. Langevin approach for the dynamics of the contact process on annealed scale-free networks. Phys. Rev. E 79, 036110 (2009).

Pastor-Satorras, R., Vázquez, A. & Vespignani, A. Dynamical and correlation properties of the Internet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 258701 (2001).

Dorogovtsev, S. N., Goltsev, A. V. & Mendes, J. F. F. Critical phenomena in complex networks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 1275 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grants No. 11275049 and the National Basic Research Program of China under Grant No. 2010CB731401.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. and Z.Z.Z. designed the research, performed the research and wrote the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, Y., Zhang, Z. Mean first-passage time for maximal-entropy random walks in complex networks. Sci Rep 4, 5365 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05365

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05365

This article is cited by

-

Two types of weight-dependent walks with a trap in weighted scale-free treelike networks

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Laminar-Turbulent Transition in Raman Fiber Lasers: A First Passage Statistics Based Analysis

Scientific Reports (2016)

-

Navigation by anomalous random walks on complex networks

Scientific Reports (2016)

-

Spectra of weighted scale-free networks

Scientific Reports (2015)

-

Effects of reciprocity on random walks in weighted networks

Scientific Reports (2014)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.