Abstract

Controlling the orientations of nanomaterials on arbitrary substrates is crucial for the development of practical applications based on such materials. The aligned epitaxial growth of single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) on specific crystallographic planes in single crystalline sapphire or quartz has been demonstrated; however, these substrates are unsuitable for large scale electronic device applications and tend to be quite expensive. Here, we report a scalable method based on graphoepitaxy for the aligned growth of SWNTs on conventional SiO2/Si substrates. The “scratches” generated by polishing were found to feature altered atomic organizations that are similar to the atomic alignments found in vicinal crystalline substrates. The linear and circular scratch lines could promote the oriented growth of SWNTs through the chemical interactions between the C atoms in SWNT and the Si adatoms in the scratches. The method presented has the potential to be used to prepare complex geometrical patterns of SWNTs by ‘drawing’ circuits using SWNTs without the need for state-of-the-art equipment or complicated lithographic processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One-dimensional nanostructures, such as single crystalline nanowires and single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs), are potentially useful as building blocks for the construction of nanoscale circuitry due to their excellent electrical characteristics1,2. SWNTs are particularly attractive because their purely carbon structures yield unprecedented ballistic electron transport properties at the 1–2 nm scale3. Controlling the orientations of these nanostructures on arbitrary substrates is crucial for the development of practical applications based on such materials, but also challenging. SWNTs and inorganic nanowires were recently shown to form aligned assemblies on certain epitaxial substrates. SWNTs tended to follow the atomic steps on well-defined crystal surfaces, such as miscut sapphire (vicinal α-Al2O3 {0001}, {1120}) or miscut quartz (vicinal α-SiO2 {1101})4,5,6,7,8,9. The guided growth of inorganic nanowires may be possible through the use of epitaxial substrates or nanosteps that form spontaneously during the annealing of substrate miscuts10. Although these atomic-step-templated methods yield relatively large-scale, well-aligned arrays of 1-D nanostructures on crystal substrates, their alignment is subject to the predetermined crystallographic orientation of the substrates or nanosteps that “spontaneously” form during annealing. These methods are not scalable because crystalline (epitaxial) substrates tend to be expensive and many of them are not compatible with conventional semiconductor process. Several attempts have been made to prepare aligned SWNTs on noncrystalline substrates. Aligned growth using external forces, such as electric fields or gas flows, has been demonstrated and alignment using substrate modification techniques, such as lithographically patterned trenches, showed potential for success11,12. However, a cost-effective method that permits the controlled growth of 1-D nanostructures on amorphous substrates is required for practical applications.

Here, we describe the preparation of nanoscale grooves obtained using ‘scratch lithography’ as a new type of alignment template for inducing the pattern-aligned growth of SWNTs on conventional SiO2/Si substrates. In this work, creating 1–2 nm deep grooves on the substrates by simply polishing them with a microscale diamond polishing powder controlled the orientations of the SWNTs. The “scratches” generated by polishing were found to feature altered atomic organizations that could be distinguished from patterns generated with conventional lithography. And the scratch patterns of lines and circles could promote the oriented growth of SWNTs through the chemical interactions between the C atoms in SWNT and the Si adatoms in the scratches. The method presented has the potential to be used to prepare complex geometrical patterns of SWNTs by ‘drawing’ circuits using SWNTs without the need for state-of-the-art equipment or complicated lithographic processes.

Scratches are a very common group of line defects that can be found everywhere. They are tribological features typically found in cases in which two materials having different hardness values strike one another. From the nano-tribological perspective, scratches are the remains between a battle between the bond strengths of the atoms in each material at the contact points. Therefore, it may possible to realize “patterns” with atomic resolution with simple scratches, by choosing proper materials pair. We tested the use of “scratch lithography”, based on a common polishing technique, to generate centimeter-long, 0.5–2 nm deep scratch arrays in flat SiO2/Si substrates, which acted as templates for the guided growth of SWNTs.

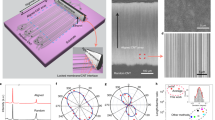

Figure 1 summarizes schematics and images of SWNT arrays formed using scratch lithography techniques. Here, the floating–polishing method was used to generate the parallel lines of scratches. In this method, an aqueous solution containing a suspension of 1 μm diamond particles was sprayed onto a disk covered with a cloth during rotation. The substrate to be polished was then turned upside-down and brought into contact with the disk to achieve polishing. As observed in the Supplementary Information Figure S1 (d), only the tips of the diamonds made contact with the substrate during polishing, yielding nanoscale grooves from the micron-sized diamond particles. Hertzian theory, which is a theoretical model based on elastic contact, offered a reasonable explanation for why polishing occurred only at the contact regions of the diamond particle tips13. According to the Hertzian model, the penetration depth of a particle into a material is determined by its Hertzian contact parameter,  , where R and k are the particle diameter and fill factor, respectively and E is the Young's modulus of the material being polished13,14. Because SiO2 typically has a modulus of around 6.6 × 1011 dyne/cm2, a rough estimate of the largest possible penetration depth is about 1.09 nm under typical polishing conditions (P = 3 psi, R = 500 nm, k = 10%, assuming spherical particle geometries). This value agreed well with the AFM results shown in Figures 1 and 2. As shown in the Supplementary Information Figure S1, larger diamond particles slightly increased the depth of the grooves and decreased the line density of the grooves.

, where R and k are the particle diameter and fill factor, respectively and E is the Young's modulus of the material being polished13,14. Because SiO2 typically has a modulus of around 6.6 × 1011 dyne/cm2, a rough estimate of the largest possible penetration depth is about 1.09 nm under typical polishing conditions (P = 3 psi, R = 500 nm, k = 10%, assuming spherical particle geometries). This value agreed well with the AFM results shown in Figures 1 and 2. As shown in the Supplementary Information Figure S1, larger diamond particles slightly increased the depth of the grooves and decreased the line density of the grooves.

Graphoepitaxial growth of SWNTs by using scratch lithography.

(a) Schematic diagram showing the scratch lithography process on a Si/SiO2 substrate using diamonds 1 μm in diameter. A SEM image of the diamonds used here is shown in inset of (a). The scale bar in (a) is 5 μm. (b) shows a schematic diagram and an AFM image of the scratched substrates and (c) depicts a schematic diagram and a SEM image of the SWNTs grown on these substrates upon the selective deposition of a ferritin catalyst over a specific surface region. The white arrows in (b) and (c) indicate the direction in which polishing was performed on the substrates. In inset of (c), the bulky regions on the left and right indicate areas that were exposed to the ferritin catalyst. The rather sparse region in the middle indicates the presence of aligned SWNTs. The scale bar in (c) is 50 μm. (d) to (f) depict the growth of SWNTs along the scratched ring patterns. (d) and (e) show the schematic and SEM image of the SWNTs grown on these substrates. The inset of (e) enlarges specific regions in the image by showing high magnification SEM images of the SWNTs grown in sectors with different scratch directions. The scale bar in inset of (e) is 25 μm. (f) shows the angular dependence of the grown SWNTs.

Surface images of the aligned SWNTs.

(a) SEM image of the aligned SWNTs (scale bar 2 μm). (b), (d) and (f) show the corresponding EFM images of the same region. (b), (d) and (f) show samples prepared under a back-gate voltage of 10 V, 0 V and −10 V, respectively. (c) Topographic AFM image of the region highlighted by the box in (a). The turquoise lines in (c) represent the SWNTs embedded in the substrate (which were invisible in the AFM image). The cross-sectional profiles of the blue and red lines marked in (c) are shown in (e), where the black dotted circles highlight regions that most likely correspond to the SWNTs of interest.

An array of SWNTs was grown on the scratched SiO2/Si substrates by photo-lithographically patterning a ferritin catalyst layer onto to the substrates. Figures 1(c) and its inset show that SWNTs grew in the grooves. The direction of SWNT growth was exactly coincidence with the direction of the grooves and was independent of the gas flow direction. The alignment of the SWNT growth was confirmed by performing identical experiments under conditions in which the patterns were arranged perpendicular to the gas flow direction (see the Supplementary Information Figure S2). It is worth mention that the lengths of aligned SWNTs on scratched substrates are generally longer than (~70 μm) that of random SWNTs grown under identical growth conditions (see the Supplementary Information Figure S3).

To demonstrate the potential of scratch lithography in terms of drawing circuits using SWNTs, we designed circularly scratched substrates as shown in Figure 1(d). Circular scratches can be achieved by implementing a rotational scratch method that spins the diamond attached lapping tape on the substrates, rather than applying linear force as mentioned in the previous paragraph. Figure 1(e) shows a low magnification scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of SWNTs grown on substrates with circular scratches and magnified images that show alignment of SWNTs at specific locations. Since the dimension of the SWNTs is much smaller than the dimension of the bird's eye view of the scratches (low magnification SEM image), such local image magnification is inevitable for the proper observation of the aligned features of the SWNTs. Three different regions that correspond to 40°, 90° and 140° were shown in the images, with SWNTs following the pattern quite faithfully. Obtaining such a feature in a single step could not be realized with the previously reported alignment techniques based on direct growth, such as epitaxial growth on crystalline substrates, gas flow or electric field assisted alignment. Figure 1(f) depicts an angular histogram of the aligned SWNTs shown in the insets of figure (e). Here, the colors of the bars in the histogram are identical to the colors used to highlight each region in the SEM image. As can be seen here the distribution of the SWNTs is very narrow for each specific angle, meaning that the scratches are very effective in lining up the SWNTs during growth.

The SWNT growth in the scratch patterns was corroborated using the physical measurements illustrated in Figure 2. Figure 2(a) shows a typical SEM image of the aligned arrays and Figures 2(b), 2(d) and 2(f) show AFM and electrostatic force microscopy (EFM) images of the same region. As shown in the AFM images, the direction of SWNT growth faithfully followed the grooves generated by the scratch patterning. It is important to point out that the SWNTs grew inside the valleys, rather than outside of them. For this reason, it was difficult to discriminate between the SWNTs from the background signal in a simple topographic AFM image, as shown in Figure 2(d). EFM images more clearly distinguished the SWNTs from the substrate background regions. Figures 2(b) and 2(f) show images obtained upon application of a 10 V and −10 V bias to the system (back gate). The growth of well-aligned conducting SWNTs was clearly distinguishable from the background, as expected. A more detailed analysis was performed in the boxed region shown in Figure 2(a) to further confirm that the SWNTs grew in the valleys only. An AFM image on this region is shown in Figure 2(c), where a false color graphic tool was used to follow the path changes displayed by the SWNTs. The cross-sectional profiles of the red and blue lines in Figure 2(c) are shown in Figure 2(e). The dashed circles in Figure 2(e) indicate the positions in which the SWNTs formed. A comparison of the two profiles implied that the SWNTs were originally positioned in the groove, as mentioned above.

The growth characteristics of the SWNTs in this system were evaluated and the structural properties of the SWNTs were investigated by Raman spectroscopy. The tangential mode observed in the Raman peak near 1580 cm−1 corresponded to a first-order Raman process and appeared upon symmetry breaking during the rolling of the graphene sheets15. SWNTs display 6 representative spectral peaks corresponding to different Raman modes, but the most dominant peaks are the G+ and G− peaks. The G+ peak originates from the atomic displacement along the tube direction, whereas the G− peak originates from atomic displacement along the circumferential direction. The aligned features of the SWNTs in this system were characterized by evaluating the angular dependence of the Raman profiles as a function of the substrate rotation, as shown in Figures 3(b) and 3(c). The Raman spectrum at a given point was collected as summarized in Figure 3(c). The peak intensities were maximal at 0° and 180° and decreased as the rotation angle approached 90°. This result agreed well with the previous Raman results reported by Dresselhaus et al.15,16 and clearly showed that the SWNTs were well-aligned on the scratched SiO2/Si substrates. A comparison of the Raman spectra of the aligned SWNTs with randomly aligned SWNTs grown on non-scratched SiO2/Si substrates revealed two notable differences, as shown in Figure 3(d). First, the G+ peak was blue-shifted in the aligned SWNT spectrum. The aligned SWNT peak occurred at an average wavenumber of 1599.82 cm−1, whereas the randomly oriented SWNTs displayed a peak at 1596.18 cm−1 (Fig. 3(e)). Previously, samples prepared by spraying a SWNT suspensions onto flat SiO2 substrates have G+ peak at 1590 cm−116 and aligned SWNT samples assisted by gas flow control exhibit G+ peak at 1585–1594 cm−117,18. On the other hand, the aligned SWNTs grown on the ST-cut quartz substrates exhibit blue shift (1600 cm−1) compared to the SWNTs grown randomly on an amorphous quartz substrate (1595 cm−1, See the Supplementary Information Figure S4 and the results reported in reference19,20). The two profiles also differed with respect to the presence of a very weak defect peak near 1344 cm−1. This peak most likely originated from the rough atomic configuration of the dangling bonds in the scratch lines. Disrupted atomic structures in the substrate can induce disorder in the six-membered ring structure of the SWNTs. It is likely that defect formation happened during the growth process, since aligned SWNTs by spraying SWNT solutions on scratched substrate did not exhibit enhanced defect-related peaks (data not shown). Taken these two distinctive Raman signatures, it is very likely that there exist significant interactions between the substrate and the SWNTs.

Raman analysis of the aligned SWNTs.

(a) Schematic illustration of the process by which Raman spectra were acquired as a function of the sample rotation. The Raman profiles collected are plotted in (b) as a function of the Raman shifts and the data were rearranged according to the G+ peak intensities in (c) to better visualize the influence of the sample rotation on the Raman spectra. Here, the dotted line represents the intensity values fitted to the equation Y = cos4(θ). (d) Comparison of the D and G peaks in the Raman spectra of the random and aligned SWNTs. The arrow in the figure points to the presence of a small D peak in the aligned substrate. (e) Summary of the average G+ peak shift values in the aligned and random SWNT samples. The differences between the Raman shift values of the G+ and G− peaks from the two types of SWNTs were analyzed and the results are summarized in (f) by plotting the Raman shift values against the calculated nanotube diameter. Here, 12 individual SWNTs were sampled in each case and the peak positions of the aligned SWNTs were deliberately shifted down by 3.64 cm−1 to facilitate a comparison.

Additional information about the SWNT diameters could be extracted from the Raman spectral analysis. Although less accurate than the results obtained from a radial breathing mode analysis, the diameters of the aligned SWNTs could be characterized based on the G+ and G− peaks using the equation  15. Here, ω0 for a unscratched SiO2 substrate was 1595.43 cm−1 and ω0 for a grooved SiO2 substrate was 1599.08 cm−1, β = −45.7 for semiconducting SWNTs and −79.5 for metallic SWNTs and n = 2. As shown in Figure 3(f), the ratio between the semiconducting and metallic SWNTs was 2:1, as in the conventional case. This ratio was confirmed using electrical measurements, as discussed below. Here, the profile of the SWNTs grown on the scratched substrate was deliberately down-shifted by 3.64 cm−1 to facilitate a comparison. Inspection of Figure 3(f) reveals that the distribution of the SWNT diameters was centered at a lower value in the aligned structures than in the randomly oriented structures due to the confinement of the SWNTs within the grooves. This implied that the experimental parameters may be fine-tuned to allow the fabrication of SWNTs with a narrow diameter distribution, suggesting that the chirality may potentially be controllable.

15. Here, ω0 for a unscratched SiO2 substrate was 1595.43 cm−1 and ω0 for a grooved SiO2 substrate was 1599.08 cm−1, β = −45.7 for semiconducting SWNTs and −79.5 for metallic SWNTs and n = 2. As shown in Figure 3(f), the ratio between the semiconducting and metallic SWNTs was 2:1, as in the conventional case. This ratio was confirmed using electrical measurements, as discussed below. Here, the profile of the SWNTs grown on the scratched substrate was deliberately down-shifted by 3.64 cm−1 to facilitate a comparison. Inspection of Figure 3(f) reveals that the distribution of the SWNT diameters was centered at a lower value in the aligned structures than in the randomly oriented structures due to the confinement of the SWNTs within the grooves. This implied that the experimental parameters may be fine-tuned to allow the fabrication of SWNTs with a narrow diameter distribution, suggesting that the chirality may potentially be controllable.

The Raman spectral results indicated the presence of strong substrate–SWNT interactions in the scratched SiO2/Si substrates. The influence of the scratch lithography on the substrates was further investigated by performing an XPS analysis of the scratched and unscratched SiO2/Si wafers. Figures 4(a) and 4(b) compare the XPS spectra of the Si 2p levels for the unscratched and scratched SiO2 samples, respectively. The unscratched SiO2 samples had an Si 2p peak at a binding energy near 103.5 eV, in good agreement with the value reported for conventional thermally grown SiO2 substrates21. By contrast, the Si 2p peak in the scratched samples was shifted toward lower binding energies, suggesting that the Si atoms in the grooves underwent reduction reactions to form SiO2–x21. Suboxide formation suggested the presence of relatively Si-rich scratch lines in which a coordinate covalent bond in the tetrahedral Si-O complex was broken. It should be noted that such lithography induced atomic rearrangement is unique for scratch lithography. As shown in the Supplementary Information Figure S5, no shift in Si 2p peak has observed in trench structures made with conventional photolithography and etching process. The XPS results determinately highlight the difference between this work and the previous reports by Orofeo and colleagues11,12. While the driving force for the alignment in the previous work is purely geometrical constriction, favorable atomic rearrangement was added to the geometrical constriction (that match with the size of SWNT) in case of scratch-induced alignment.

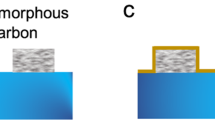

Chemical bonding analysis of the scratched SiO2 substrates.

(a) and (b) XPS profiles of the Si 2p peaks from the unscratched and scratched SiO2 substrates. The profiles suggest the presence of low oxidation state SiO2-X regions at the surfaces of the scratched sample. (c to e) Simulated models were used to investigate the structures of the unscratched and scratched silicon oxide surfaces. Si atoms are shown in orange, oxygen in red, silicon dimers in blue, hydrogen in white and carbon in gray. The gray dashed line indicates the boundaries of the supercell used here. (c) The unscratched silicon-terminated α-quartz SiO2 (0001) surface and (d) the introduction of a silicon dimer into the system. (e) Microscopic model of a GNR laying on top of the silicon dimerized surface.

The Si-rich scratch lines may interact strongly with the carbon atoms in the SWNTs to enable control over the orientation of the SWNT growth. The atomic structure and chemical reactivity of the unscratched and scratched surfaces were investigated by first-principles density functional theory (DFT) calculations using VASP22,23. The numerical methods are described in detail in the Supplementary Informations. Figures 4(c) and 4(d) show the optimized atomic geometries of the unscratched and scratched SiO2 surfaces. Here, we used a Si-terminated α-quartz (0001) surface as the unscratched SiO2 surface, as described in the SI. The Si-rich surface, as an analogue of the scratched surface, was modeled by adding two silicon atoms to the top of the 2 × 2 surface cell of the unscratched surface, as shown in Figure 4(d). The two Si adatoms formed a dimer structure with a Si–Si bond length of 2.31 Å. This Si dimer was quite stable, with a formation energy only 0.31 eV higher than that of crystalline silicon (−4.63 eV).

A Bader charge analysis24 suggested that both the adatom (Si-a) and surface (Si-s) atoms had more electrons than the silicon atoms in the bulk α-quartz (Si-b). The Bader charge values were used to assign Si charge states as follows: Si+2.72, Si+1.22 and Si+0.01 for (Si-b), (Si-s) and (Si-a), respectively. The Si charge states were clearly lower in the surface regions compared to the bulk regions and this trend was more pronounced in the Si-rich surfaces. The results agreed well with the XPS data shown in Figures 4(a) and 4(b), strongly supporting that the Si charged states were reduced upon the formation of the scratched surface.

The interactions between these scratched features and the SWNTs were investigated by simulating the interface between graphene nanoribbons (GNR) and each surface. To obtain a reasonable computational cost, a narrow GNR of one benzene ring width was used as the smallest unit bearing a resonant sp2 nature, an essential feature of SWNTs. Because the electronegativity of silicon (1.90) is much lower than that of carbon (2.55), the SWNTs interacted more strongly with Si+0.01 (Si-a) than with the more oxidized silicon derivatives, such as Si-s. The GNR was found to interact weakly with the unscratched surface (Ebind = −0.55 eV), with an equilibrium separation of about 3.4 Å, which is typical of van der Waals interaction bond length. By contrast, the Si-rich scratched surface interacted strongly with the GNR (Ebind = −0.95 eV). The carbon atoms in the GNR were even found to form chemical bonds with the surface Si dimer, yielding a C-Si bond length of ~2.0 Å. These calculations suggested that the carbon atoms were preferentially adsorbed onto the Si dimer during SWNT growth, which may potentially drive the orientated growth of SWNTs along the scratch lines.

In case of aligned SWNTs on crystalline substrate, it is generally accepted that the surface atoms form oriented “trenches” on the substrate with shallow depth to promote the alignment of SWNTs25,26,27,28. In that sense, grooves made by scratch lithography are the mimics of high-temperature annealed crystalline substrates.

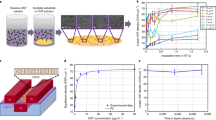

Finally, we fabricated devices having a transistor geometry using the SWNTs grown graphoepitaxially on the scratched substrates. Figures 5(a) and 5(c) show the transfer curves and SEM images (inset) of devices having semiconducting or metallic SWNTs, respectively, as the active material. Although scratch lithography introduced perturbations into the SiO2 substrate, the scale of these features was on the order of 1 nm; therefore, they did not influence the capacitance of the SiO2 layer (see the Supplementary Information Figure S6). These results suggest that SWNT-based transistor devices may be facilely controlled using this alignment control technique without requiring SWNT transfer or top gates. The inset in Figure 5(a) clearly shows the presence of 8 SWNTs between the source and drain electrodes. The output characteristics suggest that all SWNTs were semiconducting. The relationship between the number of SWNTs connected between the source and drain electrodes and the overall output current suggests that a semiconducting device will be obtained if the statistically determined number of active SWNTs is less than 10 (see the Supplementary Information Figure S7). A device prepared with more than 10 SWNTs linking the source and drain electrodes will very likely include least one metallic SWNT. These results agreed well with previous statistical studies of SWNTs, which showed that 1/3 of grown SWNTs are metallic whereas the other 2/3 are semiconducting. These results also agreed with the Raman analysis shown in Figure 3(f).

Electrical characteristics of the aligned SWNT devices prepared on scratched SiO2 substrates.

(a,b) Transfer and output characteristics of a semiconducting device prepared to have 8 SWNTs between the source and drain electrodes. The inset shows the corresponding SEM image of the device. The transfer characteristics are shown for a drain voltage of 0.5 V. (c,d) Transfer and output characteristics of a metallic device prepared to have 9 SWNTs connecting the source and drain electrodes. The inset shows the corresponding SEM image of the device for a drain voltage of 0.5 V. Because the SWNTs provided a minimum conduction path between the electrodes due to their aligned features, the fabricated devices yielded current values that were 3 times the values of their randomly oriented counterparts. The scale bars in the insets indicate 5 μm.

Conclusions

A novel scratch lithography method was introduced as an approach to guiding the random growth of SWNTs on SiO2/Si substrates with nanometer-scale precision. The mechanism underlying the growth of aligned SWNTs was examined in detail. The properties of the aligned and randomly oriented samples were compared using a variety of spectroscopic analyses and computational analyses techniques. The directional vector for SWNT growth was found to originate from the interactions between the C atoms and the Si adatom rows generated by the scratches during SWNT growth. The aligned SWNTs in this work were similar in many ways to the epitaxially grown SWNTs using conventional techniques on quartz substrates; however, scratched substrates may be used to pattern SWNT growth for the design of advanced electronic circuits on CMOS-compatible and relatively cheap substrates. The technique may be used to create simple circuit lines or nanotube loops or much more complex structures, such as nano-antennas or atomic-scale heat mediation circuits. Also, as a simple macroscopic process with atomic precision, scratch lithography could be applied varieties of substrates to introduce desirable atomic rearrangement.

Methods

1. Preparation of the scratched substrates

A grinding/polishing machine (Struers TegraPol 25) was used for the scratch process. The top side contact was covered with a cloth and the bottom side contact was formed by an attachable 10 inch magnetic fastening plate. The cloth was first soaked in an ample amount of water and a polycrystalline diamond (diameter = 1 μm) water-base suspension (Allied High Tech, 90-32015) was sprayed onto the wet clot. The plate was then spun at 150 rpm to allow the diamond particles to spread out over the entire surface. A 2 cm × 2 cm SiO2/Si substrate was flipped upside-down and gently pressed onto the machine ~10 cm away from the rotational axis. After 3 seconds of polishing, the scratched substrate was cleaned in conventional acetone, IPA, DI water baths for 10 minutes each with ultrasonication. The magnetic plate was much larger (10 inches) than the polished substrate (2 cm by 2 cm); therefore, linear scratches were generated over the entire substrate. Because the scratches were extremely small, they were invisible to both the naked eye and under optical microscopy.

2. SWNT growth

Ferritin (Sigma Aldrich, F4503) was used as a catalyst for carbon nanotube growth in this study. Ferritin was mixed with DI water in a 10:1 ratio and this fluid was dripped onto the scratched substrate. After a 15 minute incubation period, the residual solution was blown away using a nitrogen air gun. The substrate was then placed in a 1 inch atomic pressure chemical deposition (APCVD) furnace and heated to 900°C under an Ar environment. A CH4/H2 gas mixture (1000 sccm/400 sccm) was then flowed into the reactor for 10 minutes. After growth, the chamber was cooled to room temperature under an Ar environment.

3. XPS and Raman spectra

XPS analysis was performed using a ThermoScientific K-Alpha instrument in which a monochromatic Al X-ray source was used as the incident beam. The band pass energies were set to 0.02 eV to enable a more accurate peak analysis. The binding energies were compared by setting the C1s peak positions of all samples at 284.9 eV.

Raman analysis was performed under ambient conditions using a Renishaw InVia micro-Raman spectrometer equipped with a 514 nm excitation laser (E = 2.41 eV).

4. SWNT device fabrication and characterization

SWNT devices were fabricated using standard photolithographic methods in which Cr (1 nm)/Au (50 nm) source/drain electrodes were formed by thermal evaporation and defined by a lift-off process. Active channel regions were defined by photolithographic patterning and oxygen plasma etching (conducted over 15 min). The width and length of the fabricated active channel region were 40 μm and 5 μm, respectively. The electrical transport properties were characterized under ambient conditions using a Keithley 4200 semiconductor characterization system. SEM images were obtained using a MIRA II Tescan and a Dimension 3100 atomic force microscope (AFM-Veeco) was employed to observe the topographical images. Electrostatic force microscopy (EFM) measurements were performed on an instrument equipped with a Bruker Multimode 8 controller. Co/Cr-coated MESP tips (Bruker, frequency ~75 kHz) were used for the EFM in lift-mode with an elevation of 20–30 nm. A bias voltage between −10 V and 10 V was applied to samples.

References

Tans, S. J., Verschueren, A. R. M. & Dekker, C. Room-temperature transistor based on a single carbon nanotube. Nature 393, 49–52 (1998).

Cui, Y., Zhong, Z., Wang, D., Wang, W. U. & Lieber, C. M. High performance silicon nanowire field effect transistors. Nano Lett. 3, 149–152 (2003).

Javey, A., Guo, J., Wang, Q., Lundstrom, M. & Dai, H. Ballistic carbon nanotube field-effect transistors. Nature 424, 654–657 (2003).

Ismach, A., Segev, L., Wachtel, E. & Joselevich, E. Atomic-step-templated formation of single wall carbon nanotube patterns. Angew. Chem. 116, 6266–6269 (2004).

Kocabas, C. et al. Guided growth of large-scale, horizontally aligned arrays of single-walled carbon nanotubes and their use in thin-film transistors. Small 11, 1110–1116 (2005).

Han, S., Liu, X. & Zhou, C. Template-free directional growth of single-walled carbon nanotubes on a- and r-plane sapphire. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 5294–5295 (2005).

Ishigami, N. et al. Crystal plane dependent growth of aligned single-walled carbon nanotubes on sapphire. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 9918–9924 (2008).

Ding, L., Yuan, D. & Liu, J. Growth of high-density parallel arrays of long single-walled carbon nanotubes on quartz substrates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 5428–5429 (2008).

Zhou, W., Rutherglen, C. & Burke, P. J. Wafer scale synthesis of dense aligned arrays of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Nano Res. 1, 158–165 (2008).

Tsivion, D., Schvartzman, M., Popovitz-Biro, R., Huth, P. V. & Joselevich, E. Guided growth of millimeter-long horizontal nanowires with controlled orientations. Science 333, 1003–1007 (2011).

Orofeo, C. M., Ago, H., Ikuta, T., Takahasi, K. & Tsuji, M. Growth of horizontally aligned single-walled carbon nanotubes on anisotropically etched silicon substrate. Nanoscale 2, 1708–1714 (2010).

Orofeo, C. M., Hiroki, A., Yoshihara, N. & Tsuji, M. Methods to horizontally align single-walled carbon nanotubes on amorphous substrate. Kyushu University G-COE program, Journal of Novel Carbon Resource Sciences 2, 36–40 (2010).

Zhong, L. et al. A static model for scratches generated during aluminum chemical-mechanical polishing process: orbital technology. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 38, 1932–1938 (1999).

Cook, L. M. Chemical processes in glass polishing. J. Non-Cryst Solids 120, 152–171 (1990).

Jorio, A. et al. Characterizing carbon nanotube samples with resonance Raman scattering. New J. Phys. 5, 139.1–139.17 (2003).

Jorio, A. et al. G-band resonant Raman study of 62 isolated single-wall carbon nanotubes. Phs. Rev. B 65, 155412 (2002).

Jin, Z. et al. Ultralow feeding gas flow guiding growth of large-scale horizontally aligned single-walled carbon nanotube arrays. Nano Lett. 7, 2073–2079 (2007).

Huang, S., Maynor, B., Cai, X. & Liu, J. Ultralong, well-aligned single-walled carbon nanotube architectures on surfaces. Adv. Mater. 15, 1651–1655 (2003).

Ding, L. et al. Direct observation of the strong interaction between carbon nanotubes and quartz substrates. Nano Res. 2, 903–910 (2009).

Jaqueline, S. & Jorio, A. Study of carbon nanotube-substrate interaction. J. Nanotech. 2012, 512738 (2012).

Himpsel, F. J., McFeely, F. R., Taleb-Ibrahimi, A. & Yarmoff, J. A. Microscopic structure of the SiO2/Si interface. Phy. Rev. B 38, 6084–6096 (1988).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Henkelman, G., Arnaldsson, A. & Jónsson, H. A fast and robust algorithm for Bader decomposition of charge density. Comput. Mater. Sci. 36, 354–360 (2006).

Ago, H., Nakamura, K., Ikeda, K. & Uehara, N. Aligned growth of isolated single-walled carbon nanotubes programmed by atomic arrangement of substrate surface. Chem. phys. Lett. 408, 433–438 (2005).

Chiashi, S. et al. Growth of Horizontally Aligned Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes on the Singular R-Plane (10–11) of Quartz. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 6805–6808 (2012).

Xiao, J. et al. Alignment controlled growth of single-walled carbon nanotubes on quartz substrates. Nano Lett. 9, 4311–4319 (2009).

Ibrahim, I., Bachmatiuk, A., Börrnert, F., Blüher, J. & Wolff, U. Optimizing substrate surface and catalyst conditions for high yield chemical vapor deposition grown epitaxially aligned single-walled carbon nanotubes. Carbon 49, 5029–5037 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the NRF-ANR program through the National Rearch Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of education, Science and Technology (NRF-2011-K2A1A5-2011-0031552) and by a grant (2011-0031636) from the center for Advanced Soft Electronics under the Global Frontier Research Program of the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.J.C. and J.-O.L. designed the experimental part of the project. W.J.C. fabricated the devices and analyzed the samples with Raman, SEM and electrical transport measurements. Y.J.C. analyzed the substrates with XPS. W.J.C., Y.J.C., K.K., H.C. and J.-O.L. prepared figures and wrote the main manuscript text. J.H. and Y.-K.L. supervised the scratch lithography. Y.H.K. and B.G.K. performed E.F.M. analysis. K.K. and H.C. performed and analyzed the numerical simulations. J.-O.L. and Y.K.L. supervised the experimental part of the project. All authors contributed to the discussion and wrote the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Informations

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, W., Chung, Y., Kim, Y. et al. Drawing Circuits with Carbon Nanotubes: Scratch-Induced Graphoepitaxial Growth of Carbon Nanotubes on Amorphous Silicon Oxide Substrates. Sci Rep 4, 5289 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05289

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05289

This article is cited by

-

Effects of Unusual Gate Current on the Electrical Properties of Oxide Thin-Film Transistors

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Nanoscratching technique for highly oriented liquid crystal materials

Scientific Reports (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.