Abstract

Designer nucleases, like zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs), represent valuable tools for targeted genome editing. Here, we took advantage of the gamma-retroviral life cycle and produced vectors to transfer ZFNs in the form of protein, mRNA and episomal DNA. Transfer efficacy and ZFN activity were assessed in quantitative proof-of-concept experiments in a human cell line and in mouse embryonic stem cells. We demonstrate that retrovirus-mediated protein transfer (RPT), retrovirus-mediated mRNA transfer (RMT) and retrovirus-mediated episome transfer (RET) represent powerful methodologies for transient protein delivery or protein expression. Furthermore, we describe complementary strategies to augment ZFN activity after gamma-retroviral transduction, including serial transduction, proteasome inhibition and hypothermia. Depending on vector dose and target cell type, gene disruption frequencies of up to 15% were achieved with RPT and RMT and >50% gene knockout after RET. In summary, non-integrating gamma-retroviral vectors represent a versatile tool to transiently deliver ZFNs to human and mouse cells.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nuclease-mediated genome modification has evolved into an indispensable tool for basic research, biotechnology and therapeutic applications1. In particular, designer nucleases have been used for nucleotide-specific gene modification, gene disruption and targeted deletion or insertion at selected loci. Various classes of designer nucleases have been described, including meganucleases2, zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs)3, transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs)4 and RNA-guided endonucleases5. Of these, the ZFNs have been the most widely exploited thus far and are currently being investigated in a clinical trial that aims to generate autologous T cells resistant to HIV infection (e.g. NCT00842634). ZFNs are designed in pairs, with each subunit consisting of a sequence-specific DNA binding domain that is linked to a DNA cleavage domain. Hence, an active ZFN is formed following targeted binding and heterodimerisation of the ZFN subunits on opposite strands of the DNA helix6,7. The DNA binding domain typically encompasses 3 to 4 zinc fingers, each of them recognising a nucleotide triplet. When both subunits bind to the target site, the DNA is cut in the spacer sequence that separates the two target half-sites. Improvements in ZFN technology that aimed at increasing specificity and reducing ZFN-associated toxicity included better platforms to generate the DNA binding domains8, the development of obligate heterodimeric FokI cleavage domains9,10,11 and the characterisation of optimal linker/spacer combinations7,12.

The ZFN technology has been successfully applied in a variety of organisms13 and primary human cells, including T cells14, hematopoietic stem cells15, mesenchymal stromal cells16,17, keratinocyte stem cells18 and pluripotent stem cells19,20. Careful and accurate genome editing is particularly attractive for autologous stem cells, which after ex vivo gene correction can be transplanted back into the patient. However, current gene transfer methods, which enable the transient expression of designer nucleases in human stem cells, can be associated with high toxicities and/or low delivery efficiencies, thus presenting a major hurdle in the preparation of autologous gene corrected cells21. To overcome this obstacle, viral vector systems, like integrase-deficient lentiviral vectors (IDLVs), adenoviral vectors (AdV) and vectors based on adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) have been successfully employed14,22,23,24,25. Whilst nuclease expression levels from non-optimised IDLVs can be low26, AdV and AAV vectors have displayed restricted cell tropism.

Vectors based on gamma-retroviruses have been successfully used in several gene therapy studies27,28. As their parental virus, these vectors are enveloped and contain two copies of a plus-stranded RNA genome, which is capped and polyadenylated like a cellular mRNA. The viral nucleic acid in association with nucleocapsid (NC) proteins is surrounded by a shell of capsid proteins, which in turn is enclosed by an envelope derived from the host cell membrane. The viral matrix (MA) proteins are located between the capsid and the envelope (reviewed in 29). Retroviral vectors typically enter cells in a receptor-mediated manner. In the cytoplasm, the retroviral particles uncoat and reverse transcribe the plus-stranded RNA genome into a double-stranded linear proviral DNA. Upon completion of reverse transcription, a preintegration complex (PIC) containing viral DNA and cellular proteins is formed. During mitosis, the dissolution of the nuclear membrane allows the PIC to move into the nucleus where the viral integrase mediates integration of proviral vector DNA into the cellular chromosome29.

It has recently been shown that non-integrating retroviruses can serve as molecular tools for the efficient delivery of mRNA30 or proteins31,32. The retrovirus-mediated mRNA transfer (RMT) technology is based on mutations within the vector's primer-binding site, which prevents the reverse transcription of viral mRNA33. This approach has been exploited for the transient delivery of marker proteins and enzymatically active proteins, such as recombinases and transposases30,34,35. Retrovirus-mediated protein transfer (RPT) has been achieved by fusing a foreign open reading frame at either the 3′-end of the NC or MA coding sequences, or at the 5′-end of the viral p12 reading frame31. Inclusion of a protease cleavage site ensures that the foreign protein is released from NC or MA by the viral protease during maturation of the vector particles31.

In the present study we demonstrate that by exploiting retroviral particles as delivery vehicles for ZFN proteins, ZFN-encoding mRNA and DNA episomes, we can induce stable genetic modifications in a human cell line and in mouse pluripotent stem cells. We show that all three vector systems, RPT, RMT and RET, can efficiently deliver a marker protein to the target cells. Furthermore, we provide evidence of high gene knockout frequencies after transient delivery of ZFNs without eliciting significant cytotoxic side-effects.

Results

Efficient delivery of a marker protein by non-integrating retroviral particles

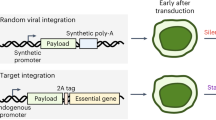

We constructed various retroviral vector scaffolds that allowed us to express a transgene using either RET or RMT particles. Moreover, the DsRed-Express (DsRex) maker protein or ZFNs were delivered by RPT through fusion of the marker to gag (Figure 1A). Efficient transgene delivery was validated by monitoring DsRex expression 1, 2 and 5 days post-transduction of the human chronic myelogenous leukaemia cell line K562, in which we introduced a single copy EGFP expression cassette in the AAVS1 locus (K562-EGFP). The influence of temperature on transgene expression was investigated by incubating the transduced K562-EGFP cells at either 30°C (hypothermia) or 37°C (normothermia). Up to 35% of cells were DsRex positive and levels from all non-integrating delivery methods were significantly higher and persisted longer under hypothermic as compared to normothermic conditions (Figure 1B). In contrast, DsRex expression from integrating vectors was detected earlier and at a higher level at 37°C.

Retrovirus-mediated transgene delivery to human cell line.

(A) Schematic of packaging system. Displayed are the cis and trans-acting retroviral elements used to generate retroviral particles. Cis elements: retroviral vector genomes containing a gene of interest (GOI) flanked by the long terminal repeats (LTRs), a primer binding site (PBS) and the woodchuck hepatitis posttranscriptional regulatory element (WPRE). Trans elements: viral sequences encoding gag and pol genes under the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter. To produce integrating retroviral vector (IRV), unmodified recombinant cis and trans-acting elements were used. For the production of retroviral episomal vectors (RET), an integrase (IN)-defective variant (IN*) of the gag/pol plasmid was utilised. For retrovirus-mediated mRNA transfer (RMT), a normal gag/pol was combined with a vector genome containing a mutated primer binding site (aPBS). For retrovirus-mediated protein transfer (RPT), only the trans-acting components were used, which contained the GOI fused to C-terminus of either the nucleocapsid (NC) or the matrix (MA) protein encoding sequences. The GOI was separated from NC or MA by a retroviral protease cleavage site. pA, polyadenylation signal; p12, viral p12 protein; CA, capsid; PR, protease; RT, reverse transcriptase. (B) DsRed-Express (DsRex) expression in K562-EGFP cells under normal and hypothermic conditions. Cells were transduced with retroviral vectors expressing DsRex (MOI of 2.5) and incubated at 37°C or at 30°C. The percentage of red cells was measured by flow cytometry at day 1, 2 and 5 post-transduction. Asterisks indicate statistically significant difference between paired samples (37°C vs. 30°C; p < 0.05; experiment repeated three times in duplicate). (C) Kinetics and dose-dependent expression of DsRex in K562-EGFP cells. Cells were transduced with increasing doses of retroviral vectors (MOI of 2.5, 25, 250). After transduction, cells were kept at 30°C for 7 days then transferred to 37°C for the rest of the experiment. Expression of DsRex was measured by flow cytometry at indicated time points.

To examine dose response and kinetics of protein expression, K562-EGFP cells were transduced with increasing amounts of the DsRex expressing vectors. After transduction, cells were maintained at 30°C for 7 days before being transferred to 37°C. Flow cytometric analysis revealed a positive correlation between vector dose and DsRex levels (Figure 1C). The highest transduction frequencies were reached with the RPT vectors, which showed delivery of DsRex in almost 100% of cells. Furthermore, DsRex expression from RET, RMT and RPT vectors remained stable during incubation at 30°C, but declined rapidly after transferring the cells to 37°C. This was in sharp contrast to the results obtained for the integrating vector, which showed reduced expression under hypothermic conditions, which then increased under normothermic conditions.

Retroviral mediated ZFN delivery allows for stable gene knockout in a human cell line

Next we used the above-described systems to deliver active ZFNs targeted to the EGFP gene8. In order to assess the activities and toxicities of these ZFN delivery vectors, we transfected the various vector plasmids into an U2OS cell line that carries 3 copies of a destabilised EGFP transgene24. ZFN mediated EGFP disruption could be detected from all retroviral vector backbones by flow cytometry (Figure S1, A). Because maturation of viral proteins takes place in the virus particles, we did not detect “mature” ZFN proteins in the transfected cells in case of the RPT vectors but only “ZFN precursors” fused to the gag proteins (Figure S1, B). Moreover, ZFN activity correlated positively with plasmid dose and negatively with cell survival, an indirect measurement of ZFN-associated toxicity (Figure S1, C).

Encouraged by these results, various gamma-retroviral particles were produced and used to transduce K562-EGFP cells. The human cell line was co-transduced with retroviral vectors expressing either ZFN subunit at an MOI of 2.5 and EGFP knockout was assessed following incubation of cells at 30°C or 37°C at days 2 and 5 post-transduction. We observed only weak knockout activity of transiently expressed ZFN under hypothermic conditions and the difference between EGFP disruption frequencies at 30°C and 37°C was not statistically significant (Figure 2A). In agreement with marker protein expression (Figure 1B), ZFN activity from integrating vectors was higher at 37°C (Figure 2A). To investigate the correlation between vector dose and ZFNs activity, K562-EGFP cells were transduced with MOIs of 2.5, 25 and 250. The cells were initially maintained at 30°C for 7 days and then transferred to normothermia. Even at the highest vector dose, ZFN activity was not detectable from RMT and RPT vectors. However, >50% gene knockout activity was detected in cells following transduction with the RET and IRV vectors (Figure 2B).

ZFN-mediated knockout in K562-EGFP cells.

(A) Temperature dependent EGFP knockout. Cells were transduced with retroviral vectors (MOI of 2.5) and incubated at 37°C or 30°C. The decline in EGFP expression was measured by flow cytometry at day 2 and 5 post-transduction. Asterisk indicates statistically significant difference between paired samples (30°C vs. 37°C; p < 0.05; experiment repeated three times in duplicate). (B) Kinetics and dose-dependence of EGFP knockout. Cells were transduced with increasing doses of retroviral vectors (MOI of 2.5, 25, 250) and kept at 30°C for 7 days before the transfer to 37°C for the rest of the experiment. Percentage of EGFP positive cells was measured by flow cytometry at indicated time points. (C) Analysis of ZFN expression. ZFN proteins were detected with anti-HA tag antibody. As loading controls, antibodies against β-actin (cell lysates) or p30 (retroviral supernatants) were used. (D) Effect of multiple retrovirus transductions and of proteasome inhibitor MG132. Cells were transduced 1, 2 or 3 times with retroviral vectors expressing ZFN constitutively (IRV) or transiently (RET, RMT, RPT-NC, RPT-MA) using an MOI of 2. MG132 was added to the cell medium after a single retrovirus transduction. EGFP expression was measured 3–4 days after the last transduction. Significant increase in the percentage of EGFP-negative cells between single and multiple transductions and MG132 treatment for the same vector type is marked with an asterisk (p < 0.05). (E) Genotyping of ZFN-treated K562-EGFP cells. Genomic DNA of triple transduced cells was used as a template for PCR amplification of the ZFN-modified EGFP locus before digestion with the mismatch-sensitive T7 endonuclease I (T7E1). The expected product lengths are indicated on the right. Open triangles indicate an unspecific DNA fragment in undigested samples. IRV, integrating retrovirus vector; RET, retrovirus-mediated episomal transfer; RMT, retrovirus-mediated mRNA transfer; RPT, retrovirus-mediated protein transfer; NC, nucleocapsid position of the transgene; MA, matrix localisation of a transgene; L, left domain of ZFN; R, right domain of ZFN. Mock values were subtracted from samples in each experiment.

To validate efficient production, packaging and processing of the ZFNs incorporated in the retroviral vector particles, we performed Western blot analysis of the virus supernatants and the lysates of the producer cells. Assessment of the producer cells indicated the presence of ZFN proteins in all producer cell lysates (Figure 2C). As expected, the ZFNs detected in the cell lysates of RPT particle producing cells were mainly present as fusions to either gag or gag/pol precursor proteins. Equal protein loading was confirmed by staining with an anti-β-actin antibody. Importantly, analysis of the retroviral particles in the supernatant revealed the presence of mature ZFN proteins in both the NC and MA RPT vector variants (Figure 2C), confirming efficient proteolytic cleavage of the ZFN proteins from their NC or MA carriers. As expected, RMT and IRV particles did not contain any ZFN proteins. Unexpectedly, the RET particles contained marginal amounts of ZFN proteins, possibly as a result of cross-packaging due to the high ZFN concentrations in the respective producer cells. Visualisation of the viral capsid protein p30 confirmed equivalent loading of virus particles (Figure 2C).

Triple transduction or proteasome inhibitor enhances ZFN-mediated knockout

Having confirmed that ZFN proteins were efficiently produced and/or properly processed within the retroviral particles, we hypothesised that low ZFN activity after cell transduction may result from insufficient intranuclear ZFN concentrations and/or rapid protein degradation. To test this hypothesis, we performed three serial consecutive transductions (every 24 h for 3 days) in K562-EGFP cells using a low vector dose. In addition we performed a single transduction in combination with the proteasome inhibitor MG132. As compared to a single transduction, repetitive infections of cells increased the level of ZFN-mediated gene disruption for all vectors (Figure 2D). In particular, RET mediated gene disruption could be increased to approximately 15% with the repetitive transduction scheme. Furthermore, the use of a proteasome inhibitor was particularly beneficial for RPT mediated EGFP knockout. With the RPT-MA vector, the percentage of EGFP negative cells increased by 3-fold when compared to non-treated cells, reaching knockout frequencies of ~10% (Figure 2D). To assess whether the treatment with proteasome inhibitors also improves gene disruption if the ZFN are delivered in the form of mRNA, K562-EGFP cells were nucleofected with synthetic mRNAs encoding the ZFNs and treated with 0.5 μM of MG132. Results show that the proteasome inhibitor enhanced ZFN-mediated EGFP knockout by 15-fold, resulting in ~29% of cells being EGFP negative (Figure S2).

To confirm that the decrease in EGFP expression was due to ZFN activity, we performed a T7 endonuclease I (T7E1) assay on genomic DNA isolated from triple transduced K562-EGFP cells. A genomic fragment encompassing the ZFN target locus was PCR amplified and subjected to treatment with T7E1 (Figure 2E). The results corresponded well with the flow cytometric data and showed that the percentage of mutated EGFP alleles was highest after transduction with IRV and RET vectors.

Retroviral ZFN delivery allows for stable gene knockout in pluripotent stem cells

To validate our delivery systems in a stem cell line, the vectors were applied to mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) carrying a single copy of the EGFP gene in the HPRT locus (mES-EGFP). Transduction with non-integrating vector systems led to higher amount of DsRex-positive cells compared to the integrative vector. Up to ~30% of DsRex-positive cells were detected and the marker could be detected longer under hypothermic conditions (Figure 3A). Moreover, we observed a linear correlation between the percentage of DsRex-positive cells and the vector dose (Figure S3). After a single round of transduction with the ZFN delivery vectors, substantial levels of EGFP knockout could only be detected with the integrating vector (Figure 3B). While the use of a proteasome inhibitor did not affect gene disruption rates in mES-EGFP cells, a triple transduction with a low dose of RET and RPT particles (MOI of 2) resulted in 9–15% EGFP-negative cells and up to 52% with the integrating system (Figure 3C). Determination of vector copy numbers revealed that about 10 integrated (IRV) or episomal (RET) genome copies are sufficient to achieve these knockout frequencies (Figure S4).

Retrovirus mediated ZFN delivery to knockout EGFP in mouse embryonic stem cells.

mES-EGFP cells containing one copy of the EGFP gene were transduced with retroviral vectors expressing either DsRex or ZFN as an integrating vector (IRV) or transiently (RET, RMT, RPT-NC, RPT-MA). DsRex expression and EGFP knockout levels were measured by flow cytometry at indicated time points. (A) DsRex expression in mES-EGFP cells under normal or hypothermic conditions. After transduction with retroviral vectors (MOI of 2.5), cells were incubated at either 37°C or 30°C for 5 days. The percentage of red cells was measured by flow cytometry at day 1, 2 and 5 post-transduction. Asterisks indicate statistically significant difference between paired samples (37°C vs. 30°C; p < 0.05; experiment repeated three times in duplicate). (B) Kinetics and dose-dependence of EGFP knockout in mESCs. mES-EGFP cells were transduced with increasing doses of retroviral vectors (MOI 2.5, 25, 250) and kept at 30°C for 5 days before being shifted to 37°C for the rest of the experiment. The percentage of EGFP-negative cells was measured by flow cytometry at the indicated time points. (C) Effect of serial transductions and of proteasome inhibitor MG132. Cells were transduced 1, 2 or 3 times with ZFN delivering retroviral vectors (MOI of 2). MG132 was added to the cell medium after a single retrovirus transduction for 12 h. EGFP expression was measured 3–4 days after the last transduction. Significant increase in the percentage of EGFP-negative cells between single and multiple transduced or MG132 treated cells, respectively, is marked by asterisk (p < 0.05). (D) Cell cycle analysis of mES-EGFP cells. Single or triple transduced mES-EGFP cells were labeled with BrdU and stained with APC-conjugated anti-BrdU antibody and 7-AAD after fixation and assessed by flow cytometry. Graphs display average values of the percentage of cells captured in the different cell cycle stages. IRV, integrating retrovirus vector; RET, retrovirus-mediated episomal transfer; RMT, retrovirus-mediated mRNA transfer; RPT, retrovirus-mediated protein transfer; NC, nucleocapsid position of the transgene; MA, matrix localisation of the transgene. Mock values were subtracted from samples in each experiment.

To assess potential toxicity of the ZFN delivery vectors, we assessed general cell survival and conducted a cell cycle analysis following single and triple transductions. While a dose-dependent toxicity stemming from viral transduction was observed, ZFN expression did not induce any additional cytotoxicity (Figure S5). Cell cycle plots of mES-EGFP cells 24 h after a single transduction with integrating or episomal retroviral particles revealed a weak G2/M arrest for IRVs (Figure 3D), however, no significant differences in the cell cycle profiles were observed after transient ZFN delivery by RET, RMT and RPT.

Discussion

Since the first generation of artificial ZFNs36, they have been developed for a large variety of biomedical applications37. Although ZFN represent a powerful tool in genome engineering, their transfer into primary cells has remained a challenge. To overcome this hurdle, ZFNs have been vectorised into various viral systems, including those based on the adeno-associated virus23,24,25, integrase-deficient lentivirus vectors (IDLV)22, adenoviral vectors14 and baculovirus38. Moreover, microinjection of mRNA encoding ZFNs into one-cell zebrafish and rat embryos proved efficient for the disruption of endogenous genes39,40,41. More recently, direct protein transfer of ZFN has been shown to successfully create a gene knockout in human cells with minimal toxicity42. With the exception of IDLVs, the above-mentioned viral vector systems have a restricted cell tropism and mRNA or protein based ZFN transfer may not be amenable for large-scale approaches. Here, we aimed at scrutinising the efficacy and safety of transient ZFN delivery by vectors based on the non-integrating gamma-retrovirus. We demonstrate in a human cell line and in mouse pluripotent stem cells that all gamma-retroviral vector systems employed, i.e. transfer of DNA episomes, mRNA or protein, allow for the efficient transfer/expression of a marker protein. Significant ZFN-mediated gene disruption activity was observed with all vector systems in a human cell line, but efficient gene disruption in mES-EGFP cells was only achieved with RET based ZFN transfer.

It is known that a few hundred retroviral particles can enter a given target cell31. Although we observed a linear correlation between the applied vector dose and expression of the reporter protein DsRex, this observation could not be extended to ZFN activity. This is most likely because a certain threshold concentration of intranuclear ZFNs is required for optimal activity. Here, we identified three accompanying strategies to increase ZFN activity in retrovirally transduced cells: a serial transduction scheme, hypothermia and inhibition of proteasome mediated degradation. It has previously been shown that repeated retrovirus transduction of hematopoietic stem cells augments transgene expression levels43. In accordance with these findings our data demonstrates that triple transduction of K562-EGFP cells and mES-EGFP using low retroviral vector doses significantly improved ZFN activity, leading to higher EGFP disruption rates. Of note, quantitative determination of retroviral genome copies revealed that 2 to 10 episomal copies of the ZFN expression vector are sufficient to achieve gene knockout frequencies in the double-digit range.

It has also been reported that a transient cold-shock can enhance ZFN activity following cell transfection44, though the mechanism behind this observation has remained undefined. Based on our results we cannot draw any definite conclusions about the impact of hypothermia on ZFN activity, however, our data on the transfer efficiency of a marker gene/protein suggests that transient hypothermia extends the half-life of the non-integrating viral vector systems in the cell. This is in line with a previously reported observation45, but it is important to mention that expression from the integrating retroviral vector was considerably higher at normothermia46. Hence, to establish the direct effect of temperature on the retroviral life cycle in general and on retrovirus-mediated ZFN delivery in particular, further experiments will be needed.

To prevent rapid ZFN turnover within transduced cells, we treated infected cells with the proteasome inhibitor MG132. Two studies have previously reported on the beneficial effect of MG132 treatment with retroviral and lentiviral based gene transfer in human and mouse cells34,47. Moreover, it has been shown that the proteasome inhibitor MG132 increases the stability of zinc-finger proteins upon cell transfection48,49 and enhances gene disruption rates in a cell line49. The results obtained in this report revealed a beneficial effect of proteasome inhibition on ZFN-mediated knockout efficiencies in K562-EGFP cells transduced with RMT and RPT vectors or nucleofected with synthetic mRNA. On the other hand, MG132 had no noticeable effect on ZFN activity in mES-EGFP cells. We speculate that the fast proliferation rate of these cells leads to rapid ZFN dilution. Alternatively, the feeder cells may compromise both viral transduction efficiency50 and the effect of MG132. Indeed, in comparison to somatic cells, mouse ESCs display some unique cell cycle features, like a very short G1 phase and the lack of a G1/S checkpoint51. Most of the ESCs reside in the S phase (60–70%) and the duration of a cell cycle (10–12 h) is extraordinarily short51,52. We observed a weak G2/M phase arrest in mES-EGFP cells transduced with integrating ZFN expression vectors, indicative of DNA damage. Similar observations were made previously after treatment of ESCs with DNA damage-inducing agents, like ionising radiation52. The absence of cell cycle arrest after transient ZFN expression from non-integrating vectors underscores the notion that continuous ZFN expression can lead to significant DNA damage. Moreover, stable integration of a transgene cassette is intrinsically associated with a higher risk of insertional mutagenesis and malignant transformation53. Hence, the non-integrating delivery platforms described here may offer a suitable alternative for transient ZFN expression in many mammalian cell types.

On the whole, we obtained considerable gene disruption efficiencies for all the transient-delivery retroviral vectors without the need of selection. Further improvements need to be made to increase the transduction efficiency of target cells. In the context of retroviral vectors this can be achieved by modifying the vector envelope with a cell type specific ligand, for which receptors are present on the target cell surface in a great abundance. Such an approach will not only ensure cell specific uptake of the vector but may also enable higher concentration of the ZFN, leading to improved activity. Finally, the retroviridae family is known to be exceptionally amendable to pseudotyping54. Various studies have shown increased specificity of gene transfer with vectors pseudotyped with RD114 glycoprotein to various stem cells55,56, pseudotyping with measles virus glycoprotein to target plasma cells57, or display of antibodies or DARPins to transduce hematopoietic progenitor cells or cancer cells50,58.

The work presented here introduces a novel concept for ZFN delivery to cells by means of non-integrating gamma-retroviral vectors. In our study, we demonstrated the versatility of this platform in obtaining targeted gene knockouts in a human cell line and in murine embryonic stem cells. Importantly, when assessing toxic side effects of our approach, we showed that unlike integrating retroviral vectors, the vectors used for transient ZFN expression do not alter the cell cycle profile in the transduced cells. In conclusion, our versatile gamma-retroviral ZFN transfer system allows researchers to deliver ZFNs in the form of DNA, mRNA and protein, thereby enlarging the toolbox available to genome engineers and offering novel attractive ways of ZFN delivery for various biological applications.

Methods

Plasmids

For this study, codon-optimised (Mr. Gene; Regensburg, Germany) zinc-finger arrays targeting EGFP gene at position 2928 were fused to the obligate heterodimeric FokI variant EA-KV9 by the 4 AA linker LRGS12. Plasmids for gamma-retroviral vector production were derived from pRSF9135 or pMLV31. Plasmids for the production of integrating vectors (IRV) and vectors for retrovirus-mediated mRNA transfer (RMT) were generated by replacing the Flpo gene in pRSF91.Flpo.gPRE and pRSF91.aPBS.Flpo.gPRE30 with ZFN and DsRex, respectively. Vector plasmids for retroviral-mediated protein transfer (RPT-NC, RPT-MA) were generated by replacing the EGFP gene in pcDNA3.NC.Prot.GFP and pcDNA3.MA.Prot.GFP31 with ZFN or DsRex. All plasmid sequences can be obtained upon request.

Cells

A human chronic myelogenous leukaemia cell line (K562) stably expressing an EGFP gene from the AAVS1 locus was prepared by nucleofection of K562 cells (ATCC) with the pAAVS1_SA2APuro_PGK_EGFP_HSVtkpA plasmid (created by cloning PGK-EGFP-HSVtkpA cassette into Addgene plasmid #22075) along with AAVS1-specific ZFN expression plasmids19. After initial selection with 0.5 μg/ml of puromycin (Invitrogen), single cell clones were analysed by PCR and a clone containing a single targeted integration of the EGFP expression cassette was chosen for further experiments. K562-EGFP cells were cultured in RPMI medium (Gibco/Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% FCS (Gibco/Life Technologies), 100 IU penicillin and 10 mg/ml streptomycin (P/S; PAA Laboratories GmbH, Austria) and 2 mM L-glutamine (PAA Laboratories). The murine embryonic stem cell line BK4-G3, containing a single copy of the EGFP gene in the HPRT locus, has previously been described20. Cells were grown on gamma-irradiated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) in knockout DMEM (Gibco/Life Technologies) supplemented with 15% FCS (PAN Biotech, Berlin, Germany), leukaemia inhibitory factor (LIF)-conditioned medium produced from recombinant Chinese hamster ovary cells (diluted 1:500), P/S, 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids (PAA Laboratories) and 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Gibco/Life Technologies).

Gamma-retroviral particles

Retroviral supernatants pseudotyped with vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G) were produced by transient transfection of 293T cells31,35. Supernatants were collected 36 h and 60 h after transfection and concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 82,740× g and 4°C for 2 h. Virus pellets from two 10 cm plates were resuspended in 300 μl of PBS and frozen in small aliquots at −80°C. For titration 8 × 104 U2OS-EGFP cells containing three copies of an EGFP gene25 were transduced with serial dilutions of concentrated virus supernatants for 1 h by centrifugation at 200× g in the presence of protamine sulphate (4 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich), followed by incubation with viruses for another 12–16 h. The percentage of EGFP-negative or DsRex-positive cells was measured by flow cytometry 24–48 h after transduction. The number of transducing units was calculated using the formula: (No × Nt)/D, where No stands for percentage of EGFP-negative/DsRex-positive cells, Nt the number of transduced cells, D the dilution factor59. K562-EGFP cells were transduced using the spinoculation method. Briefly, 48-well plates were covered with Retronectin (Takara, Otsu, Japan). Concentrated virus supernatant (MOI of 2.5, 25 or 250) was added in 200 μl of culture medium without FCS and plates centrifuged at 400× g at 4°C for 30 min. 1 × 105 cells in 100 μl of serum-free RPMI medium containing 4 μg/ml protamine sulphate were added per well before centrifugation at 200× g at 30°C for 1 h. Then, wells were supplemented with 100 μl of RPMI medium with FCS to obtain a final serum concentration of 10%. For the triple transduction protocol, cell transductions were repeated every 24 h. Where indicated, the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Calbiochem) was added to medium at 0.5 μM overnight. Murine ES-EGFP cells were transduced in 24-well plates coated with 0.1% porcine gelatine (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were trypsinised and feeders removed by using 70 μm cell filters (Millipore). 1 × 105 cells in 100 μl of serum-free ES medium was added to wells containing retrovirus supernatants (MOI = 2.5, 25 or 250) and protamine sulphate (4 μg/ml) in a total volume of 400 μl. Cells were centrifuged at 200× g for 1 h at 30°C. Then, 200 μl of complete mES medium containing ES-FCS was added to obtain a final serum concentration of 15%. In case of multiple transductions, the first and second transductions were performed on feeder cells. For the third transduction cells were trypsinised and re-plated on a 12-well plate covered with 0.1% gelatine. Where indicated, cells were incubated at 30°C, otherwise at 37°C.

Western blotting

Protein detection from cell lysates and concentrated retroviral supernatants was performed as previously described34 with minor adjustments. Briefly, U2OS-EGFP cells transfected with ZFN expression plasmids were harvested 48 h after transfection, while 293T producer cells were collected 60 h post-transfection. Cells were lysed in 100 ml of ice-cold RIPA buffer composed of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Nonidet P-40 and a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Complete Mini, Roche Applied Science). Samples were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (12%) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. ZFN and EGFP expression was detected using antibodies directed against the HA tag (NB600-363; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO) and EGFP (MAB3580; Millipore, Billerica, MA), respectively. Control staining was performed using anti-α-actin (sc-81178, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or anti-p30 antibodies (kindly provided by Sandra K. Ruscetti, NCI Frederick, MA, USA). Proteins were visualised after staining with HRP-conjugated mouse anti-rabbit, (Dianova) mouse anti-rat (Dianova), or donkey anti-goat (Santa Cruz) secondary antibody using the WestPico Chemiluminescence substrate (Thermo Scientific).

Genotyping

ZFN-mediated EGFP disruption was analysed on a genomic level in K562-EGFP cells using the T7 endonuclease I (T7E1) assay as previously described20. Briefly, 100 ng of genomic DNA was used in a PCR reaction to amplify a 556 bp fragment of the EGFP locus, with primers#154 5′-CTACGGCAAGCTGACCCTGAA (forward) and #155 5′-GAACTCCAGCAGGACCATGT (reverse) using Phusion High Fidelity DNA polymerase (Thermo Scientific). 100 ng of purified amplicon was subjected to T7E1 digestion (5 U, New England Biolabs) for 20 min at 37°C in NEB buffer 2, before separation on a 2% agarose gel. Quantification of the cleavage was performed using the Quantity One software (Bio Rad).

Cell cycle analysis

K562-EGFP and mES-EGFP cells were transduced with retroviral vectors at an MOI of 2. After 24 h 1 μM of BrdU was added to the cell culture medium for 45 min (K562-EGFP) or 20 min (mES-EGFP). After washing with PBS, cells were harvested, fixed and stained with 7-AAD and anti-BrdU antibody (APC BrdU Flow Kit; BD Pharmingen), before flow cytometric analysis (FACS Calibur, Becton Dickinson).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the paired Student's t test. Significant differences of p < 0.05 are indicated by asterisks.

References

Wirt, S. E. & Porteus, M. H. Development of nuclease-mediated site-specific genome modification. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 24, 609–616 (2012).

Stoddard, B. L. Homing endonucleases: from microbial genetic invaders to reagents for targeted DNA modification. Structure 12, 7–15 (2011).

Urnov, F. D., Rebar, E. J., Holmes, M. C., Zhang, H. S. & Gregory, P. D. Genome editing with engineered zinc finger nucleases. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 636–646 (2010).

Mussolino, C. & Cathomen, T. TALE nucleases: tailored genome engineering made easy. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 23, 644–650 (2012).

Cong, L. et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339, 819–823 (2013).

Smith, J. et al. Requirements for double-strand cleavage by chimeric restriction enzymes with zinc finger DNA-recognition domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 3361–3369 (2000).

Bibikova, M. et al. Stimulation of homologous recombination through targeted cleavage by chimeric nucleases. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 289–297 (2001).

Maeder, M. L. et al. Rapid “open-source” engineering of customized zinc-finger nucleases for highly efficient gene modification. Mol. Cell. 31, 294–301 (2008).

Szczepek, M. et al. Structure-based redesign of the dimerization interface reduces the toxicity of zinc-finger nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 786–793 (2007).

Miller, J. C. et al. An improved zinc-finger nuclease architecture for highly specific genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 778–785 (2007).

Doyon, Y. et al. Enhancing zinc-finger-nuclease activity with improved obligate heterodimeric architectures. Nat. Methods 8, 74–79 (2011).

Händel, E. M., Alwin, S. & Cathomen, T. Expanding or restricting the target site repertoire of zinc-finger nucleases: the inter-domain linker as a major determinant of target site selectivity. Mol. Ther. 17, 104–111 (2009).

Carroll, D. Genome engineering with zinc-finger nucleases. Genetics 188, 773–782 (2011).

Perez, E. E. et al. Establishment of HIV-1 resistance in CD4+ T cells by genome editing using zinc-finger nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 808–816 (2008).

Holt, N. et al. Human hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells modified by zinc-fingernucleases targeted to CCR5 control HIV-1 in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 839–847 (2010).

Benabdallah, B. F. et al. Targeted gene addition to human mesenchymal stromal cells as a cell-based plasma-soluble protein delivery platform. Cytotherapy 12, 394–399 (2010).

Rahman, S. H. et al. The nontoxic cell cycle modulator indirubin augments transduction of adeno-associated viral vectors and zinc-finger nuclease-mediated gene targeting. Hum. Gene Ther. 24, 67–77 (2013).

Höher, T., Wallace, L., Khan, K., Cathomen, T. & Reichelt, J. Highly Efficient Zinc-Finger Nuclease-Mediated Disruption of an eGFP Transgene in Keratinocyte Stem Cells without Impairment of Stem Cell Properties. Stem Cell Rev. 8, 426–434 (2012).

Hockemeyer, D. et al. Efficient targeting of expressed and silent genes in human ESCs and iPSCs using zinc-fingernucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 851–857 (2009).

Osiak, A. et al. Selection-independent generation of gene knockout mouse embryonic stem cells using zinc-finger nucleases. PLoS One 6, e28911 (2011).

Cao, F. et al. Comparison of gene-transfer efficiency in human embryonic stem cells. Mol. Imaging Biol. 12, 15–24 (2010).

Lombardo, A. et al. Gene editing in human stem cells using zinc finger nucleases and integrase-defective lentiviral vector delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 1298–1306 (2007).

Li, H. et al. In vivo genome editing restores haemostasis in a mouse model of haemophilia. Nature 475, 217–221 (2011).

Händel, E. M. et al. Versatile and efficient genome editing in human cells by combining zinc-finger nucleases with adeno-associated viral vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 23, 321–329 (2012).

Ellis, B. L., Hirsch, M. L., Porter, S. N., Samulski, R. J. & Porteus, M. H. Zinc-finger nuclease-mediated gene correction using single AAV vector transduction and enhancement by Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs. Gene Ther. 20, 35–42 (2013).

Cornu, T. I. & Cathomen, T. Targeted genome modifications using integrase-deficient lentiviral vectors. Mol. Ther. 15, 2107–2113 (2007).

Cavazzana, M. Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy: progress on the clinical front. Hum. Gene Ther. 25, 165–170 (2014).

Nienhuis, A.W. Development of gene therapy for blood disorders: an update. Blood 122, 1556–1564 (2013).

Maetzig, T., Galla, M., Baum, C. & Schambach, A. Gammaretroviral vectors: biology, technology and application. Viruses 3, 677–6713 (2011).

Galla, M., Will, E., Kraunus, J., Chen, L. & Baum, C. Retroviral pseudotransduction for targeted cell manipulation. Mol. Cell. 16, 309–315 (2004).

Voelkel, C. et al. Protein transduction from retroviral Gag precursors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 7805–7810 (2010).

Maetzig, T., Baum, C. & Schambach, A. Retroviral protein transfer: falling apart to make an impact. Curr. Gene Ther. 12, 389–409 (2012).

Lund, A. H., Duch, M., Lovmand, J., Jørgensen, P. & Pedersen, F. S. Complementation of a primer binding site-impaired murine leukemia virus-derived retroviral vector by a genetically engineered tRNA-like primer. J. Virol. 71, 1191–1195 (1997).

Galla, M., Schambach, A., Towers, G. J. & Baum, C. Cellular restriction of retrovirus particle-mediated mRNA transfer. J. Virol. 82, 3069–3077 (2008).

Galla, M. et al. Avoiding cytotoxicity of transposases by dose-controlled mRNA delivery. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 7147–7160 (2011).

Kim, Y. G., Cha, J. & Chandrasegaran, S. Hybrid restriction enzymes: zinc finger fusions to Fok I cleavage domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 1156–1160 (1996).

Davis, D. & Stokoe, D. Zinc finger nucleases as tools to understand and treat human diseases. BMC Med. 8, 42 (2010).

Lei, Y. et al. Gene editing of human embryonic stem cells via an engineered baculoviral vector carrying zinc-finger nucleases. Mol. Ther. 19, 942–950 (2011).

Doyon, Y. et al. Heritable targeted gene disruption in zebrafish using designed zinc-finger nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 702–708 (2008).

Meng, X., Noyes, M. B., Zhu, L. J., Lawson, N. D. & Wolfe, S. A. Targeted gene inactivation in zebrafish using engineered zinc-finger nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 695–701 (2008).

Geurts, A. M. et al. Knockout rats via embryo microinjection of zinc-finger nucleases. Science 325, 433 (2009).

Gaj, T., Guo, J., Kato, Y., Sirk, S. J. & Barbas, C. F. 3rd. Targeted gene knockout by direct delivery of zinc-finger nuclease proteins. Nat. Methods. 9, 805–807 (2012).

Li, Z. et al. Predictable and efficient retroviral gene transfer into murine bone marrow repopulating cells using a defined vector dose. Exp. Hematol. 31, 1206–1214 (2003).

Doyon, Y. et al. Transient cold shock enhances zinc-fingernuclease-mediated gene disruption. Nat. Methods 7, 459–460 (2010).

Kotani, H. et al. Improved methods of retroviral vector transduction and production for gene therapy. Hum.Gene Ther. 5, 19–28 (1994).

Stephenson, J. R., Tronick, S. R. & Aaronson, S. A. Temperature-sensitive mutants of murine leukemia virus. IV. Further physiological characterization and evidence for genetic recombination. J. Virol. 14, 918–923 (1974).

Santoni de Sio, F. R., Cascio, P., Zingale, A., Gasparini, M. & Naldini, L. Proteasome activity restricts lentiviral gene transfer into hematopoietic stem cells and is down-regulated by cytokines that enhance transduction. Blood 107, 4257–4265 (2006).

Pruett-Miller, S. M., Reading, D. W., Porter, S. N. & Porteus, M. H. Attenuation of zinc finger nuclease toxicity by small-molecule regulation of protein levels. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000376 (2009).

Ramakrishna, S., Kim, Y. H. & Kim, H. Stability of zinc finger nuclease protein is enhanced by the proteasome inhibitor MG132. PLoS One 8, e54282 (2013).

Zhang, X. & Roth, M. J. Antibody-directed lentiviral gene transduction in early immature hematopoietic progenitor cells. J. Gene Med. 12, 945–955 (2010).

Aladjem, M. I. et al. ES cells do not activate p53-dependent stress responses and undergo p53-independent apoptosis in response to DNA damage. Curr. Biol. 8, 145–155 (1998).

Chuykin, I. A., Lianguzova, M. S., Pospelova, T. V. & Pospelov, V. A. Activation of DNA damage response signalling in mouse embryonic stem cells. Cell Cycle 7, 2922–2928 (2008).

Kustikova, O. et al. Clonal dominance of hematopoietic stem cells triggered by retroviral gene marking. Science 308, 1171–1174 (2005).

Cronin, J., Zhang, X. Y. & Reiser, J. Altering the tropism of lentiviral vectors through pseudotyping. Curr. Gene Ther. 5, 387–398 (2005).

Jang, J. E. et al. Specific and stable gene transfer to human embryonic stem cells using pseudotyped lentiviral vectors. Stem Cells Dev. 15, 109–117 (2006).

Di Nunzio, F., Piovani, B., Cosset, F. L., Mavilio, F. & Stornaiuolo, A. Transduction of human hematopoietic stem cells by lentiviral vectors pseudotyped with the RD114-TR chimeric envelope glycoprotein. Hum. Gene Ther. 18, 811–820 (2007).

Schoenhals, M. et al. Efficient transduction of healthy and malignant plasma cells by lentiviral vectors pseudotyped with measles virus glycoproteins. Leukemia 26, 1663–1670 (2012).

Münch, R. C. et al. DARPins: an efficient targeting domain for lentiviral vectors. Mol. Ther. 19, 686–693 (2011).

Gallardo, H. F., Tan, C., Ory, D. & Sadelain, M. Recombinant retroviruses pseudotyped with the vesicular stomatitis virus G glycoprotein mediate both stable gene transfer and pseudotransduction in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Blood 90, 952–957 (1997).

Acknowledgements

We thank Raffaele Altamura, Anne-Kathrin Dreyer, Olga Kustikova, Tobias Maetzig, Adrian Schwarzer (all Institute of Experimental Hematology, Hannover Medical School), Christien Bednarski, Shamim Rahman, Kristie Bloom and Claudio Mussolino (all Institute for Cell and Gene Therapy, University Medical Center Freiburg) for technical support, experimental advice and/or critical comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the European Commission's 7th Framework Programme [PERSIST-222878 to T.C. and C.B.]; the German Research Foundation [SFB 738-C4 to C.B.; SFB 738-C9 to T.C. and A.S.; REBIRTH Cluster of Excellence to A.S. (EXC 62/1) and to J.A. (fellowship)]; and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research [BMBF 01 EO 0803 to T.C.].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.B.W., M.G., A.S. and T.C. designed the studies; S.B.W., J.K. and M.G. prepared viral vectors and determined vector copy numbers; J.A. generated and characterised the K562-EGFP cell line; S.B.W. performed the experiments; S.B.W., C.B., A.S. and T.C. discussed the experimental data; S.B.W. and T.C. wrote the manuscript; all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Data

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. The images in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the image credit; if the image is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the image. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Bobis-Wozowicz, S., Galla, M., Alzubi, J. et al. Non-integrating gamma-retroviral vectors as a versatile tool for transient zinc-finger nuclease delivery. Sci Rep 4, 4656 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04656

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep04656

This article is cited by

-

CRISPR Takes the Front Seat in CART-Cell Development

BioDrugs (2021)

-

The Functionality of Minimal PiggyBac Transposons in Mammalian Cells

Molecular Therapy - Nucleic Acids (2016)

-

Improved Cell-Penetrating Zinc-Finger Nuclease Proteins for Precision Genome Engineering

Molecular Therapy - Nucleic Acids (2015)

-

Efficient delivery of nuclease proteins for genome editing in human stem cells and primary cells

Nature Protocols (2015)

-

Novel lentiviral vectors with mutated reverse transcriptase for mRNA delivery of TALE nucleases

Scientific Reports (2014)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.