Abstract

Wild birds are suspected to have played a role in highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 outbreaks in West Bengal. Cluster analysis showed that H5N1 was introduced in West Bengal at least 3 times between 2008 and 2010. We simulated the introduction of H5N1 by wild birds and their contact with poultry through a stochastic continuous-time mathematical model. Results showed that reducing contact between wild birds and domestic poultry and increasing the culling rate of infected domestic poultry communities will reduce the probability of outbreaks. Poultry communities that shared habitat with wild birds or those indistricts with previous outbreaks were more likely to suffer an outbreak. These results indicate that wild birds can introduce HPAI to domestic poultry and that limiting their contact at shared habitats together with swift culling of infected domestic poultry can greatly reduce the likelihood of HPAI outbreaks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 (hereafter H5N1) first emerged in 1996 in Eastern Asia and has been circulating amongst avian populations since then. Today, H5N1 has spread into parts of Asia, Europe, Africa and the Middle East. The 2005 H5N1 outbreak in China's Qinghai Lake migratory birds resulted in more than 6000 bird mortalities1,2. Subsequent migratory wild bird mortalities were observed in the same year in Mongolia, Kazakhstan, western parts of China and Eastern Europe3,4. Migratory birds are known to carry the infection5 which supports the hypothesis they may have played a role in the spread of H5N16. However, some believe that it is unlikely for a bird to carry such highly pathogenic virus during the physiologically taxing activity of migration7. In contrast, the spread of H5N1 along wild bird migratory routes may be explained by recent studies suggesting that previous exposure of birds to low pathogenic avian influenza may provide resistance to H5N18. Furthermore, it is also suggested that there might be instances where the virus is transmitted in cycles of infections in bird flocks during migration9. A global study investigating sources of H5N1 infections in poultry in 2006 indicated that 3 out of 21 outbreaks in Asia were introduced by migratory birds10.

India's first H5N1 outbreak was reported in January of 2006 in the Navapur District, Maharashtra, India. Since then H5N1 has been reported in 8 different states. In West Bengal, 54 H5N1 outbreaks in poultry were reported between Jan 2006 and Aug 2010 making it the state with highest incidence in India11. Very few studies have been conducted about the epidemiology of H5N1 outbreaks in India. Gilbert and others studied the epidemiological risk factors associated with the migrations of sentinel species in the area of West Bengal and adjacent Bangladesh9. Adhikari and others estimated the disease incidence using an ecological niche modeling tool12. Fewer large-scale monitoring studies have been conducted to estimate the prevalence of H5N1 in wild birds in India13,14. HPAI models created until now have considered a single introduction of virus from wild birds to poultry. Others concerning wild birds have included a continuous transmission model in wild birds exclusively15. Few mathematical models included both wild birds as well as poultry with continuous contact with each other16,17. To date, H5N1 outbreaks in India are restricted to poultry except for outbreaks in Jungle Crow (Corvus macrorhynhos) that took place in February 201211. Models describing such outbreaks have focused on poultry dynamics18,19. Hence, modeling H5N1 outbreaks with continuous contact between wild birds and poultry along with studies focusing on risk factors related to wild birds in India are lacking.

Much work has been done to model bird migration and correlating the spatial and temporal migration pattern with the spread of H5N1. Many studies illustrated migration as stopovers4,20,21. A modeling study about disease dynamics in bar-headed geese Anser indicus indicated these wild bird populations suffer greater mortality during the autumn versus spring migration due to the higher number of outbreaks in the autumn22. Bourouiba et al (2011) also studied the interaction between poultry and migratory birds sustaining virus over long periods in China23. However, H5N1 viruses, if present, are thought to generally be at very low prevalence among migratory birds. Few samples have been collected from live birds in the region of this study24 and except for recent outbreaks in crows in India there are no reports of the virus in wild birds from India11. Thus studies of less than 10,000 birds are not likely to detect HPAI25. Larger studies estimate low prevalence (2.7%) of H5 subtypes elsewhere in the World26. Although the H5N1 virus is now endemic in the study region, it is speculated that the first introductions were because of migratory birds10. It is well documented that viruses do circulate in wild bird populations and that the virus populations grow at waterfowl wintering grounds. Thus it is reasonable to conclude in this study that first introductions of H5N1 were through migratory birds. The current study illustrates infection dynamics of H5N1 virus in wintering grounds of West-Bengal assuming that the first introduction of the virus is from a migratory bird.

The focus of this research was to describe the epidemiology of H5N1 outbreaks in West Bengal, India from 2008 to 2010. The first objective was to describe the regional epidemiology of H5N1, spatio-temporal clusters and transmissibility as estimated by the basic reproductive number. Second, a stochastic mathematical model was designed to investigate the role of wild bird congregations in the regional epidemiology of H5N1 in West Bengal and a sensitivity analysis was performed to identify potentially effective control measures for H5N1 transmission. The model specifically illustrates the dynamics of the disease in poultry as well as wild bird congregations (which is a mixture of resident and wintering migratory birds), unlike previous models mentioned which simulate spread during migration. Finally, risk factors relating to wild migratory bird congregations and H5N1 outbreaks in poultry in West Bengal were investigated.

Results

We conducted a series of analysis on the epidemiological data on H5N1 outbreaks in poultry in West Bengal. Here we present results for spatio-temporal cluster analysis, basic reproductive number estimation, stochastic modeling for disease dynamics in wild birds and poultry and identify important risk factors related to wild birds for H5N1 outbreaks in West Bengal.

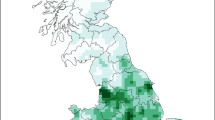

Cluster analysis

One most likely spatial cluster of 95.92 km radius (p <0.01) and two secondary spatial clusters were identified. Temporal cluster analysis showed that all the outbreaks under the study in the time frame of 1st January 2008 to 1st December 2010 were clustered into a single temporal cluster. The spatio-temporal cluster analysis also showed one most likely cluster and two secondary clusters. Location and time frame of spatio-temporal clusters are presented in Figure 1 and details of these clusters, time frames and relative risks are presented in Table 1.

Basic Reproductive Number R0

Three R0 calculation methods were used and yielded very similar estimates. The formula for SI disease models described by Ward et al27 estimated the mean of the transmission parameter β at 0.127 (Supplementary Table S1) with values that were exponentially distributed (μ = 0.122). The estimate for R0, assuming a seven-day infectious period prior to culling, was 0.859 (±0.326 S.D.). Doubling time of the outbreak was calculated to be 10 days from observed data and hence R0 was calculated to be 1.069. The mean number of times an outbreak was source to a future outbreak, based on the outbreak site being nearest neighbor in previous seven days, was 0.969 (±0.182 S.D.). The estimate for R0 based on the simulated outbreak was 1.034. Descriptive statistics for the R0 estimates are presented in Table 2.

Stochastic Model

The mean time to maximum number of infected villages in 1000 iterations showed an epidemic curve with a peak at the 80th day of introduction of infection. On average 1.91% of villages suffered an outbreak during the study period while 98.5% of villages remained susceptible after the peak of the epidemic. Descriptive statistics of susceptible, infected and culled villages and peak time are presented in Table 3.

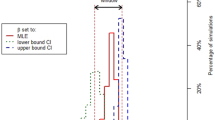

Sensitivity analysis for the model inputs showed that besides the transmission parameters for wild birds and poultry, the proportion of wild birds sharing the habitat with poultry (V) and culling rate (Cu) had the next greatest influence on H5N1 transmission. For β, the Spearman Rank correlation coefficient estimate with R0 was 0.90 and for number of villages infected at peak was 0.93. Reducing the β to half resulted in an increase in the probability of no outbreak from 0.93 to 0.99 and reduced the estimate for R0 from 1.034 to 1.00. When V was reduced systematically from 0.5 to 0.1 in decrements of 0.1, R0 decreased from 1.034 to 1.027 while the probability of no outbreak increased from 0.93 to 0.95. In addition, the number of villages infected at the end of the epidemic was reduced from 172 to 113 as V was changed from 0.5 to 0.1. When Cu was reduced from 7 to 3 days R0 changed from 1.0283 to 1.000, while the probability of no outbreak increased from 0.94 to 0.98. Combination of Cu = 0.3 and V = 0.2 resulted in a substantial increase in the probability of no outbreak to 0.99 and a reduction in R0 to 1.002. Spearman correlation coefficients are depicted in Figure 2.

Correlation between model inputs and number of infected villages at the peak of the outbreak predicted by a continuous-time stochastic SIC-SIRS mathematical model for Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 transmission in wild birds and poultry in West Bengal, India.

B = Transmission Factor in poultry; Cu = Culling rate in poultry (per day); Iw = Number of Initial wild bird congregations infected with H5N1; V = Proportion of wild birds sharing habitat and having some kind of direct contact with poultry communities; ww = Rate of waning immunity in wild birds after recovery from H5N1 (per day); Bw = Transmission factor in wild birds; rw = Recovery rate in wild birds upon infection with H5N1 (per day).

Logistic regression model

Domestic ducks sharing the same habitat with wild birds and previous history of outbreak in the same district were the only two significant predictors for an H5N1 outbreak in poultry (Table 4). Previous history of outbreaks in the same district increased the odds of suffering outbreaks by 4.07 (95% confidence interval; 1.34–12.4). Model results were adjusted for the distance from a village's wild bird community which was found to be a confounder of the association between shared habitat and occurrence of an H5N1 outbreak.

Discussion

The current study is the first epidemiological investigation of H5N1 outbreaks in West Bengal to apply spatial, statistical and mathematical modeling tools to investigate the role of wild birds in the spread of the disease in poultry. This is the first study to estimate R0 for outbreaks in West Bengal. In addition, this is the first study to compare wild bird related risk factors. Stochastic model results and conclusions from the risk factor analysis, both indicate that domestic poultry, especially domestic ducks, sharing habitat with wild bird congregations is an important risk factor in predicting H5N1 outbreaks in poultry. Mathematical modeling of H5N1 transmission showed that reducing contact between poultry (β) remains the most important factor for controlling the spread of the disease. Sensitivity analysis of the stochastic model indicated that the mixing of domestic birds and wild birds was the most influential wild bird related variable influencing the probability of occurrence of an outbreak. The two most influential factors were poultry related. Previous models of avian influenza related to wild birds reported on the dynamics of the infection in the wild birds during migration, specifically from ‘breeding ground' to ‘wintering ground' and back to ‘breeding ground'28,22. The current study focused on wintering grounds migration flux that occurs in the Indian subcontinent during the winter months from November to February. The virus is known to be carried over long distances from the northern breeding grounds circulating in the wild bird population (a mix of local resident wild birds and migratory wild birds) and poultry. Galworthy et al described a slight delay in the migration because of the persistent infection28. Pre-immunization of wild birds with low pathogenic avian influenza is known to reduce the intensity of HPAI infection29 and is modeled in detail by Bourouiba et al23. Even though there are observations of low pathogenic viruses in wild birds in India14,24 our model does not account for changes due to prior possible LPAI infection.

Risk factors analyzed in the study indicated that locations with constant interaction between wild birds and poultry may play an important role in transmission of HPAI from wild birds to poultry. Small ponds in every village specifically built for fishing by locals are generally considered the main sites where wild birds and domestic ducks co-mingle. Rice-duck-human interactions are speculated to create ideal conditions to sustain HPAI, especially in the state of West Bengal30. A study conducted in Thailand also confirmed the role of domestic waterfowl in sustaining HPAI31.

Outbreaks of H5N1 in the West Bengal India between 2008 and 2010 were not randomly distributed in time and space. Spatio-temporal differences in outbreaks indicated that the H5N1 virus was introduced at least three times in the susceptible populations between 2008 and 2010. Phylogenetic studies done on virus isolates from these outbreaks also indicate that there have been multiple sources of the virus in the country during the early phase I outbreaks32. This study may be limited by possible under reporting of outbreaks due to the lack of formal reporting systems in remote villages, or underreporting by backyard poultry farmers because of fear of possible economic loss and restriction on poultry business. This explains the difference in observed and predicted number of infected villages. Underreporting may also explain the low R0 estimated in this study. However, reporting of backyard poultry deaths may have changed because of the compensation offered by government for submitting ailing birds for culling33. Government authorities responded to each outbreak by implementing depopulation, disinfection and serological surveillance of sentinel poultry birds. These interventions might have influenced distribution of the disease. Understanding the impact of these interventions is very difficult as the outcome in absence of these interventions is never observed34.

Estimates of R0 with nearest neighbor method, SI method and epidemic doubling time ranged from 0.859 to 1.069. The R0 estimates may inform decision makers whose responsibility is to devise control strategies. The variation of the R0 from 0.859 to 1.069 indicates there might be multiple primary sources for the outbreak and this should be further investigated35. R0 estimated using the SI model was considerably lower than 1 (0.859 ± 0.328 S.D.). However, the outbreak did take place. This phenomenon may be explained by under reporting of infected villages as indicated in table S1 by several weeks of zero infected villages after the start of the epidemic (Table: S1) which in turn biased the mean value of R0 to below 1.

The estimates of R0 from the three methods used in this study vary considerably from previously reported estimates. Liu et al16 estimated R0 to be 3.3 while Bouma et al36 estimated it at 1.6 using mathematical models. While the H5N1 outbreak in Romania in 2006 had an estimated R0 ranging from 1.95 to 2.68 based on 161 infected villages27. The current study is based on only 33 outbreaks in West Bengal.

It is essential to estimate the R0 using different methods, because R0 depends on contact patterns between susceptible and infectious individuals or populations27. The methods used in estimation of R0 assume that a population of village poultry was infectious for 7 days. Other studies estimate the incubation period of the disease to be 2–6 days or sometimes 1–4 days37,38. However, studies which consider the village as its epidemiological unit consider 7 days as infectious period because accurate estimates of the period of infectiousness are unavailable27. A similar assumption was made where nearest infectious neighbor population was considered to be source of the new outbreak. While the real mechanism of virus spread might be due to movement of poultry or wild birds, through live markets, or fomites, the closest infectious village to each outbreak was assumed to be the source of infection39,40,41. Control strategies can be aimed at reducing R0 to less than one and hence reduce the critical coverage proportion of vaccination to achieve herd immunity in future prevention efforts.

Modeling results are useful in understanding the size of an HPAI outbreak which helps decision-makers to formulate control measures to avoid or control future outbreaks, something that was lacking after the 2008–2010 outbreaks33. The International Office of Epizootics states that places with large wetlands and high density of poultry in contact with wild birds can be a very important risk factor and prevention measures can be concentrated in such regions42. Prevention measures include reducing the contact between wild birds and domestic ducks by not allowing the domestic birds to forage freely near wetlands. Educational programs, targeting backyard flock owners should recommend reducing the contact between poultry and wild birds, reporting suspect cases and expedited culling to reduce the risk of HPAI transmission.

Wild birds carry avian influenza viruses from their breeding to wintering grounds. This study indicated that contact between wild birds and poultry is one risk factor for outbreaks. The state of West Bengal is a major rice producing state, producing two crops per year unlike other states that produce a single crop per year. In addition, West Bengal has large numbers of domestic ducks that interact with wild birds and poultry. These ducks generally graze and swim in the same habitat where migratory ducks and other wild birds congregate. HPAI virus can be easily transmitted at such places via fecal oral route. Control of the virus spread should be concentrated in water-bodies shared between wild birds and domestic ducks and poultry. Surveillance can be targeted on such water-bodies where wild birds and domestic ducks share habitat. Organized poultry farms need to increase their biosecurity to prevent outbreaks, including keeping domestic ducks separate from other poultry and reducing contact between their poultry flocks and wild birds.

Methods

Data collection

The National Institute of Virology and the Ela Foundation of India collected migratory bird data as part of an avian influenza surveillance project in 2010. The data included observations of known wintering grounds along with incidentally found congregations on large natural water-bodies, flooded rice fields and reservoirs. Data available regarding avian influenza risk factors for these congregations included avian community size, habitat, sentinel species, species previously known positive for H5N1, bridge species and occurrence of domestic ducks in the same water-body43,44,45. Observations were done using standard “point count” techniques by authors (SP and PP)46. Previous observations and ornithological records suggest that the observed risk factors at these wintering water-bodies remain constant from one migratory season to the next47,48. We used data on outbreaks which occurred during the years 2008 to 2010 in West Bengal (available from the OIE World Animal Health information Database (WAHID). The data included reported bird mortalities, outbreak cases and susceptible birds during the outbreaks.

Cluster analysis

Spatial, temporal and spatio-temporal cluster analyses were performed using SatScan. Clusters were calculated based on number of cases occurring in an outbreak and susceptible population using a discrete Poisson model49 (equation 1).

Where X is number of events and W is the size of the window scan. Subsequently, clusters were mapped in ArcMap (ArcGIS 10.0 ESRI Inc., Redland CA) along with the spatial means of the clusters (World Topographic Map, ArcGIS 10.0 ESRI Inc., Redland CA.; 1970 Datum, Stereographic 70 Projection).

Estimation of basic reproductive number

The basic reproductive number (R0) is the mean number of secondary cases caused by an infectious individual during its entire infectious period when introduced to a fully susceptible population50. The epidemiological unit of interest in this study is the village; hence the basic reproductive number was defined as the expected number of secondary outbreaks arising from a single individual village outbreak during the entire follow up period. R0 was calculated by SI modeling method, nearest infectious neighbor method, epidemic doubling time method. Details of the methods used are described in similar previous studies27.

Stochastic mathematical model

Wild migratory birds are asymptomatic carriers of the virus and may infect local wild birds or poultry at their wintering grounds. Different hypotheses have been put forth, explaining the mechanism of wild migratory birds carrying the virus over long distances4,9,51. In contrast to previous models which considered wild birds to be a one-time infectious source which is specified as a single signal in the model, the current study assumed that wild birds can continuously interact and have contact with poultry at a specific rate. Hence, wild birds could be a continuous source of infection to other wild birds and poultry. We constructed a stochastic continuous-time mathematical model based on frequency dependent transmission, which assumed that the number of adequate contacts was independent of number of poultry or wild bird congregations (Figure 3). Frequency dependent transmission was justified by that a village was considered infected if exposed to adequate contact for transmission of HPAI from a single or several infected wild birds. The domestic-wild bird transmission model design was a SIC-SIRS model for the change in disease status of a poultry flock in a village from susceptible (S), infected (I) and culled (C) and wild birds in a wild bird congregation from S, I, recovered (R) and S again.

Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 Disease Dynamics: Infection in poultry communities is described by a SIC model and in wild bird communities is by a SIRS model.

Interactions between poultry and wild birds are depicted as dotted lines. HPAI transmission is governed by the probabilities depicted at every transmission.

Each village was considered to have both poultry and wild bird groups susceptible to HPAI infection. Once a flock was infected in a village, it was assumed that the entire village was infected and will be culled. Model assumptions included no decrease in the population of wild birds as evidence suggests the mortality due to HPAI is likely to be minimal9,52,53,54. The proportion of poultry communities having possible connection by sharing the same water-body or via bridge avian species (syn-anthropic wild bird species) among the wild bird congregations were estimated as a stochastic parameter (V) due to inherent variability in its value. The transmission rate between an infected poultry community to a susceptible one (β) was derived from the R0 estimated using SI method based on the field data. In contrast, the transmission rate between wild birds and from wild birds to poultry communities (βW) was based on a previous study of avian influenza dynamics in wild birds17. The following are the ordinary differential equations used for the continuous time-stochastic mathematical model for transmission of HPAI in wild birds and poultry in West Bengal India:

where:

-

SD = Proportion of susceptible villages with domestic poultry

-

ID = Proportion of infected villages with domestic poultry

-

CD = Proportion of villages with culled poultry

-

Sw = Proportion of susceptible wild bird congregations

-

Iw = Proportion of infected wild bird congregations

-

Rw = Proportion of recovered wild birds

-

β = Transmission factor for transmission of H5N1 between domestic poultry communities

-

βw = Transmission factor for transmission of H5N1 from wild birds to domestic poultry communities and between wild birds

-

V = Proportion of wild birds in all forms of sufficient contact with domestic poultry

-

Cu = Culling rate of infected domestic poultry

-

rw = recovery rate of infected wild birds

-

wW = Rate at which natural immunity wanes in wild birds

Estimation of stochastic model parameters

The model assumed all the villages (n = 37,945) in the state of West Bengal to be susceptible poultry communities along with an estimated equal number of wild bird congregations55. The outbreak started with the introduction of a single infected community of wild birds, hence IW (t = 1) was estimated at 1/37,945, while ID (t = 1) was zero. The β estimate based on the SI model of observed data was found to be exponential distributed (μ = 0.122691). The βW was estimated at 1.00E-0817. Infected poultry were either completely culled or dead within 7 days of the infection and hence a fixed cull rate of 1/7 was assumed for the entire study period. Waning immunity in infected wild birds was estimated to be 0.038/day based on a previous study17. During the survey of wild birds in West Bengal it was observed that almost half of the wild bird congregations have contact with poultry by sharing the same habitat or by presence of bridge species. Hence V, an estimate of the adequate contact between wild birds and poultry was determined to be 0.5 and introduced into the model as a stochastic parameter that is normally distributed (SD = 0.1). Recovery rate of infected wild birds (rw) was considered to be 17 days54. The R0 was estimated using the total infected villages at the end of the outbreak56.

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to investigate the effect of different model inputs on number of infected villages and rank inputs by importance. The Spearman Rank correlation coefficient was used to estimate the correlation between each of the model's stochastic inputs and the number of infected villages at the peak of the outbreak. The probability of no outbreak (total infected villages < than 1), R0 and the number of villages infected at the peak of the outbreak were recorded to investigate the effect of varying the model inputs on these outcomes.

Risk factor analysis

Risk factors influencing the incidence of HPAI are well known44 hence the current study focused on risk factors related to wild birds which might affect the incidence of disease in poultry. Specifically, sightings of birds of Orders Galliformes and Charadriiformes which are considered sentinel species and syn-anthropic wild birds which serve as bridge species44 in the vicinity of poultry HPAI outbreaks were investigated. Remaining risk factors studied related to the critical community size (CCS) which is defined as the number of individuals able to maintain infection in an environment for certain period of time. The CCS for HPAI was estimated to be 1200–1500 birds which considering the habitat in which wild birds are found, large water-bodies may play a very important role in maintaining the infection. For example, presence or proximity to rice fields is known to be an important risk factor30. Other factors investigated are shared habitats between domestic ducks allowed to graze in water bodies with migratory birds, a common practice in places in West Bengal. Hence for the risk factor analysis CCS, habitat of the observed congregation57, presence of previously known HPAI infected species58, sentinel species and bridge species in the avian community of the congregation and presence of domestic ducks in the same habitat59 were considered.

Fifty-four random points were generated in the map of West Bengal as controls. Nearest observed wild bird community was used as predictors for both outbreaks and controls. Logistic regression was used to study the association between the various putative risk factors (mentioned before in the paragraph above) and the presence of HPAI infection. The association was estimated as the ratio of the odds of exposure to a risk factor in a village with H5N1 infected poultry to the odds of exposure to that risk factor in an uninfected village. A forward manual step-wise model building algorithm was implemented with a two-sided P value ≤0.10 for the inclusion of a risk factor in the model was used. Competing models were compared using the likelihood ratio test. The final model's goodness of fit was assessed using the deviance with a chi square test. Confounding of the association between sharing of habitat by poultry and wild birds and presence of a H5N1 outbreak in poultry by each of the risk factors was assessed using the method of change in estimates. The model was adjusted for a confounder if inclusion of the variable changed the estimated ORs by more than 10%60.

The logistic regression model was a generalized linear model with a logit link. The model predicted the log odds of the probability of an H5N1 outbreak in the ith domestic flock as predicted by putative risk factors and was formulated as below:

References

Chen, H. et al. Avian flu: H5N1 virus outbreak in migratory waterfowl. Nature 436, 191–192 (2005).

Liu, J. et al. Highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus infection in migratory birds. Science 309, 1206 (2005).

Normile, D. Avian influenza. Wild birds only partly to blame in spreading H5N1. Science 312, 1451 (2006).

Gilbert, M. et al. Anatidae migration in the western Palearctic and spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12, 1650–1656 (2006).

Sun, G. A. Y., Huanhuan. A Study on the Space-Time Dynamic of Global Avian Influenza and Relationship with Bird Migration. Int. J. Business Management 3, 10–17 (2008).

Olsen, B. et al. Global patterns of influenza a virus in wild birds. Science 312, 384–388 (2006).

Weber, T. P. & Stilianakis, N. I. Ecologic immunology of avian influenza (H5N1) in migratory birds. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13, 1139–1143 (2007).

Kalthoff, D. et al. Highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (H5N1) in experimentally infected adult mute swans. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14, 1267–1270 (2008).

Gilbert, M. et al. Flying over an infected landscape: distribution of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 risk in South Asia and satellite tracking of wild waterfowl. EcoHealth 7, 448–458 (2010).

Kilpatrick, A. M. et al. Predicting the global spread of H5N1 avian influenza. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 19368–19373 (2006).

OIE WAHID. 2011. Office International des Epizooties–World Animal Health Information Database (WAHID) Interface.See http://www.oie.int/wahis/public.php?page=home (accessed on 11/04/2011).

Adhikari, D., Chettri, A. & Barik, S. Modelling the ecology and distribution of highly pathogenic avian influenza (H5N1) in the Indian subcontinent. Curr. Sci. 97, 73–78 (2009).

Pawar, S. et al. Avian influenza surveillance in wild migratory, resident, domestic birds and in poultry in Maharashtra and Manipur, India, during avian migratory season 2006–07. Curr. Sci. 97, 550–554 (2009).

Pawar, S. et al. An avian influenza A (H11N1) virus from a wild aquatic bird revealing a unique Eurasian-American genetic reassortment. Vir. genes 41, 14–22 (2010).

Roche, B. et al. Water-borne transmission drives avian influenza dynamics in wild birds: the case of the 2005–2006 epidemics in the Camargue area. Infect., Genet. Evol. 9, 800–805 (2009).

Liu, R., Duvvuri, V. & Wu, J. Spread pattern formation of H5N1-avian influenza and its implications for control strategies. Math. Model. Nat. Phenom. 3, 161–179 (2008).

Vaidya, N. K., Wang, F. B. I. N. & Zou, X. Avian influenza dynamics in wild birds with bird mobility and spatial heterogeneous environment. Discrete Cont. Dyn-B. 17, 2829–2848 (2012).

Rao, A. Modeling the rapid spread of avian influenza (H5N1) in India. Math. Biosci. Eng. 5, 523–537 (2008).

Rao, A. S. & Rao, S. Location of the epicenter of avian bird flu might determine the rapidity of its spread in India. Curr. Sci. 95, 314–315 (2008).

Si, Y. et al. Spatio-temporal dynamics of global H5N1 outbreaks match bird migration patterns. Geospatial Health 4, 65–78 (2009).

Newman, S. H. et al. Eco-virological approach for assessing the role of wild birds in the spread of avian influenza H5N1 along the Central Asian Flyway. PloS one 7, e30636, 10.1371/journal.pone.0030636 (2012).

Bourouiba, L. et al. Spatial dynamics of bar-headed geese migration in the context of H5N1. J. R. Soc. Interface 7, 1627–1639 (2010).

Bourouiba, L., Gourley, S. A., Liu, R. & Wu, J. The interaction of migratory birds and domestic poultry and its role in sustaining avian influenza. Siam J. Appl. Math. 71, 487–516 (2011).

Pawar, S. D. et al. Avian influenza surveillance reveals presence of low pathogenic avian influenza viruses in poultry during 2009–2011 in the West Bengal State, India. Virology Journal 9, 1–7 (2012).

Lewis, N. S. et al. Avian Influenza Virus Surveillance in Wild Birds in Georgia: 2009–2011. PloS one 8, e58534, 10.1371/journal.pone.0058534 (2013).

Munster, V. J. et al. Spatial, temporal and species variation in prevalence of influenza A viruses in wild migratory birds. PLoS Pathog 3, e61, 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030061 (2007).

Ward, M. P., Maftei, D., Apostu, C. & Suru, A. Estimation of the basic reproductive number (R0) for epidemic, highly pathogenic avian influenza subtype H5N1 spread. Epidemiol. Infect. 137, 219–226 (2009).

Galsworthy, S. J. et al. Effects of infection-induced migration delays on the epidemiology of avian influenza in wild mallard populations. PloS one 6, e26118, 10.1371/journal.pone.0026118 (2011).

Pasick, J. et al. Susceptibility of Canada geese (Branta canadensis) to highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (H5N1). Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13, 1821–1827 (2007).

Patil, R. R. Avian flu: examining role of ducks in Indian context. Indian J. Community Med. 35, 209–210 (2010).

Gilbert, M. et al. Avian influenza, domestic ducks and rice agriculture in Thailand. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 119, 409–415 (2007).

Chakrabarti, A. K. et al. Characterization of the Influenza A H5N1 Viruses of the 2008–09 Outbreaks in India Reveals a Third Introduction and Possible Endemicity. PLoS One 4, e7846. 10.1371/journal.pone.0007846 (2009).

Chakraborti, C. Pandemic management and developing World bioethics: Bird Flu in West Bengal. Dev. World Bioeth. 9, 161–166 (2009).

Ward, M. P., Maftei, D., Apostu, C. & Suru, A. Geostatistical visualisation and spatial statistics for evaluation of the dispersion of epidemic highly pathogenic avian influenza subtype H5N1. Vet. Res. 39, DOI: 10.1051/vetres,2007063 (2008).

Rothman, K. J. Epidemiology: An Introduction. (Oxford University Press, New York, 2002).

Bouma, A. et al. Estimation of transmission parameters of H5N1 avian influenza virus in chickens. PLoS Pathog 5, e1000281. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000281 (2009).

Mannelli, A., Busani, L., Toson, M., Bertolini, S. & Marangon, S. Transmission parameters of highly pathogenic avian influenza (H7N1) among industrial poultry farms in northern Italy in 1999–2000. Prev. Vet. Med. 81, 318–322 (2007).

Tiensin, T. et al. Transmission of the highly pathogenic avian influenza virus H5N1 within flocks during the 2004 epidemic in Thailand. J. Infect. Dis. 196, 1679–1684 (2007).

De Benedictis, P. et al. Field and laboratory findings of the first incursion of the Asian H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus in Africa. Avian Pathol. 36, 115–117 (2007).

Normile, D. Are wild birds to blame? Science. 310, 426–428 (2005).

Sims, L. et al. Origin and evolution of highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza in Asia. Vet. Rec. 157, 159–164 (2005).

OIE. The global strategy for prevention and control of H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza. (FAO, Rome, 2007).

Martin, V. et al. Epidemiology and ecology of highly pathogenic avian influenza with particular emphasis on South East Asia. Dev. Biol. 124, 23–36 (2006).

Guberti, V. & Newman, S. H. Guidelines on wild bird surveillance for highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus. J. Wildl. Dis. 43, Supplement S29–S34 (2007).

Globig, A. et al. Ducks as sentinels for avian influenza in wild birds. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15, 1633–1636 (2009).

Bibby, C., Jones, M. & Marsden, S. Expedition field techniques bird surveys. Vol. 44 (Expedition Advisory Centre, Royal Geographical Society, 1998).

Li, Z. W. D., Mundkur, T. & Bakewell, D. Status Of Waterbirds In Asia: Results Of The Asian Waterbird Census, 1987–2007. (Wetlands International, Kuala Lumpur Malaysia., 2009).

Sinha, A., Hazra, P. & Khan, T. Population Trends and Spatiotemporal Changes to the Community Structure of Waterbirds in Birbhum District, West Bengal, India. Proc. Zoo. Soc. 64, 96–108 (2011).

Kulldorff, M. Spatial scan statistics: models, calculations and applications. In: Scan statistics and applications, 303–322 Birkhauser, Boston USA, (1999).

Thomas, J. C. & Weber, D. J. Epidemiologic methods for the study of infectious diseases. (Oxford University Press, New York, 2001).

Newman, S. H. et al. Migration of Whooper Swans and Outbreaks of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 Virus in Eastern Asia. PloS One 4, e5729. 10.1371/journal.pone.0005729 (2009).

Keawcharoen, J. et al. Wild ducks as long-distance vectors of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (H5N1). Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14, 600–607 (2008).

Chen, H. et al. Establishment of multiple sublineages of H5N1 influenza virus in Asia: implications for pandemic control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 2845–2850 (2006).

Hulse-Post, D. et al. Role of domestic ducks in the propagation and biological evolution of highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza viruses in Asia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 10682–10687 (2005).

Goverment of West Bengal, I. Official site of Goverment of West Bengal, India, <http://www.westbengal.gov.in/> (2011) (accessed on 18/04/2011).

Dietz, K. The estimation of the basic reproduction number for infectious diseases. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2, 23–41 (1993).

Gilbert, M. et al. Mapping H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza risk in Southeast Asia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 4769–4774 (2008).

Islam, M. & Rahmani, A. R. Important Bird Areas In India: Priority Sites For Conservation. Indian Bird Conservation Network, Bombay Natural History Society and Birdlife International (Oxford University Press, UK, 2004).

Ward, M. P., Maftei, D. N., Apostu, C. L. & Suru, A. R. Association between outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza subtype H5N1 and migratory waterfowl (family Anatidae) populations. Zoonoses Public Health 56, 1–9 (2009).

Rothman, K. J., Greenland, S. & Lash, T. L. Modern Epidemiology. (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008).

Acknowledgements

Funding for this project was provided by the Narotam Sekhsaria Foundation (Mumbai, India) and the School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis (USA). The authors would like to thank Drs. A. C Mishra, Director National Institute of Virology, Pune, India, Shailesh Pawar, Head Avian Influenza Group, National Institute of Virology, Pune, India and Bruno Chomel, Department of Population Health and Reproduction, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis for facilitating this international collaboration and acknowledge the Ela foundation, India for undertaking this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Risk factor data collection: PP, SP. Conceived and designed mathematical model: PP, SA. Statistical and spatial analysis: PP, SA. Biological input on mathematical and statistical models: DB. Wrote first draft of the manuscript: PP. Wrote and critically reviewed the final manuscript: DB, SP, SA.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Table S1

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Pandit, P., Bunn, D., Pande, S. et al. Modeling highly pathogenic avian influenza transmission in wild birds and poultry in West Bengal, India. Sci Rep 3, 2175 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02175

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep02175

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.