Key Points

-

Highlights an audit project that aimed to improve the delivery of dietary advice to patients as part of periodontal prevention and begin translating the science to clinical application.

-

Suggests that use of the entire dental team can be effective in educating patients on the risk factors for periodontal disease.

Abstract

Aims and objectives An audit was carried out to assess the delivery of dietary advice in general dental practice for patients diagnosed with chronic/aggressive periodontitis, with the objective of finding ways to deliver dietary advice and improve patient education on a potentially important modifiable risk factor.

Methodology Following a retrospective pilot sample, an initial sample of 50 patients (of dentists, a dental therapist and dental hygienist) was selected. The delivery of dietary advice and the method by which it was given was recorded as part of the data set. A semi-structured interview was also completed to discuss various aspects of delivering dietary advice. A staff meeting was carried out following the first cycle to raise awareness and inform on the link between diet and periodontal disease. Following this a second cycle was carried out to complete the audit cycle and the results were analysed.

Results It was evident that following the first cycle dietary advice was not being given with respect to periodontal prevention. While the standard set was not met following re-audit there was significant improvement in the delivery of dietary advice as well as different ways to deliver the information. The feedback from the semi-structured interview suggested various obstacles in delivering dietary advice including lack of knowledge at first and also overloading patients with too much information initially.

Conclusion Using the entire dental team can be an effective way of educating our patients on risk factors for periodontal disease. It is important to note that this audit focused on clinicians delivering the advice and future direction should consider patient compliance and uptake of information.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic periodontitis is a ubiquitous inflammatory disease having a prevalence of 45% in the adult population,1 with 11.2% worldwide showing severe periodontal breakdown.2

While the disease process is complex and not completely understood, there is substantial evidence in the literature that it arises as a result of an imbalance in the host inflammatory/immune response to plaque bacteria. Therefore, the main treatment modalities in primary care are aimed at removing the infective stimulus and preventing activation of this dysregulated response, as well as providing an oral environment that is conducive to long term home care.

Mechanical removal of plaque has been shown to be inefficient as a single form of periodontal therapy, considering the prevalence of periodontal disease has remained unchanged. Contemporary research has therefore shifted, with an interest in therapies that can alter the host response to bacterial challenge.

Risk factors play a huge part in management of periodontal disease as well as having medico-legal implications. It is essential that clinicians identify any local (eg calculus, crowding, probing pocket depth) and systemic risk factors (eg smoking, drugs, genetics, diabetes), and inform the patient of them in order to help personalise ways in which to control the inflammatory process.

While diet has been implicated in periodontal disease for years, it is only recently that we are beginning to understand some of the mechanisms by which it can modulate the host's immune/inflammatory systems and affect periodontal inflammation. With this growing body of evidence, the 2011 European Workshop on Periodontology suggested dietary recommendations for the prevention and treatment of periodontal disease. This includes increasing dietary fibre, fish oil, fruit and vegetables and reducing intake of refined sugars.3

This audit will explore whether clinicians in a primary care setting are giving diet advice as part of periodontal therapy/prevention as well as looking at how the advice is being given, if at all.

Aims

The aim of this clinical audit is to benefit patients in primary dental care by providing a way to consistently educate on the importance of diet, a modifiable risk factor, in periodontal disease.

The objectives are to:

-

Assess how general dental practitioners view diet as a risk factor and if they are aware of the association it has with periodontal inflammation

-

Look at whether advice from the 2011 consensus is being given as part of a periodontal prevention/treatment regime and if not, why not

-

Identify ways in which we can deliver diet advice specific to periodontal treatment/maintenance to patients

-

Increase delivery of dietary information to our patients.

Method

A retrospective pilot study was carried out to assess the suitability of sample sizes for the main audit, in particular assessing whether the criteria of BPE score 4 or * provide a large enough sample with our patient base. This pilot also helped define a sensible standard and can provide a baseline for existing practice.

Following this a first prospective cycle was carried out (October–December 2014) with a sample size of 50 (n = 50) and the data collected included:

-

Whether diet advice is being given and recorded in the clinical notes

-

How diet advice is being given, if at all

-

Who was giving the diet advice (dentist, therapist, hygienist, nurse)

-

Feedback from dental professionals delivering the information was taken via semi-structured interview to identify any barriers to delivering the information.

The total sample taken included 10 patients from:

-

3 dentists

-

1 hygienist

-

1 therapist.

Following data collection from the first cycle, changes were implemented looking at ways to improve delivery of dietary information specific to periodontal disease to patients. Patient information leaflets were produced, reinforced by verbal advice from different team members. A semi-structured interview was also carried out with all of the dental professionals involved (see Appendix 1 for the interview questions asked). All staff members (dentists, hygienists, therapists, nurses) were also involved in a staff meeting where a detailed explanation of what diet advice should be given was presented. An article aimed at the dental team was also produced as part of a strategy to disseminate the information into the wider dental community and at the time of writing has been accepted for publication in Dental Update.

A second cycle (January–March 2015) was then carried out looking for improvements and the results analysed.

Results

Pilot

The purpose of the pilot study was to identify suitable selection criteria for patients who would be included within the audit data. It also helped to identify a realistic standard for the audit.

The pilot was carried out in a retrospective manner and selected patients attending the practice from July–September 2014 for either examination or treatment. The selection criteria identified are shown in Figure 1. The data collected showed that at this point in time dietary advice was not being considered at all as part of periodontal prevention. It was considered that carrying out a first cycle without informing the participating clinicians of the requirement of offering diet advice to periodontitis patients would inevitably produce the same results and therefore a brief explanation of diet and its effect on periodontal health was given to clinicians as well as the type of advice to give. They were also informed the audit was to be carried out in this area.

Standard set

The standard set following this pilot was: '70% of all patients who meet the set criteria should receive diet advice as part of a periodontal prevention programme.'

First and second cycle

The results from the first cycle showed that diet advice was given to 22% (n = 11) of patients as seen from the clinical records (Fig. 2). Of this advice 100% was verbal; no written advice was available to patients at that point.

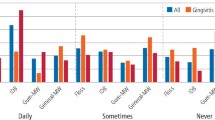

Of further note, the results demonstrated a fairly even balance in who was delivering the information between dentists and hygienists/therapists from the first cycle. Unfortunately, at the time of carrying out the audit, the oral health educator had other work commitments. Therefore, it was difficult to set up an oral health promotion meeting with a focus on nutrition and periodontal disease as originally anticipated. Hence, there was no delivery of diet advice via this route.

The main themes identified from the semi-structured interviews completed following the first cycle are highlighted in Table 1.

Following the implemented changes, the second cycle showed a great improvement in clinicians giving dietary advice. The advice was being given to 68% (n = 34) of patients randomly selected (Fig. 3) and 100% of this advice was written advice supplemented by verbal explanation of the leaflet. At this point leaflets were only being given to patients at the chair side and were not available in the reception area. Furthermore, there was still an even balance in who was delivering the information as shown in Figure 3.

Discussion

The results of this audit show promise for the delivery of dietary advice with respect to periodontal disease prevention. It must first be understood that this is a novel approach to periodontal therapy and as research behind its application is in its infancy there has been little in the way of clinical guidance. Therefore, clinicians do not routinely suggest it as a potential risk factor for periodontal disease. This means that explaining diet as a risk factor essentially requires a behaviour change on behalf of the prescribing dental professional.

Though the target which was defined following the pilot was not met, there was a significant increase to 68% of suitable patients receiving some form of dietary advice. It should also be considered that, to the authors' knowledge, this audit has not been carried out before and therefore the percentage target set is not based on any prior audit cycles. However, it is clear that with a rapidly expanding evidence base and clear written information on the relationship of nutrition and periodontal disease, the value of a good diet on the periodontium is becoming increasingly important to the dental team.

Furthermore, the limitations of this audit must be considered – one being that as a prospective audit, the data was collected based on clinical notes. While it is pragmatic to record the fact that diet advice has been given, it is currently unlikely that failure to inform a patient of its relationship with periodontal breakdown would attract litigation due to the developing evidence. It is of far more importance that established risk factors such as smoking, poor oral hygiene/marginal inflammation, increased probing pocket depth and poorly controlled diabetes are noted down. This was highlighted during the semi-structured interview where clinicians did consider the priority of different risk factors and suggested that this may play a role in not providing diet advice initially.

On reflection, therefore, the target set at 70% may not account for the fact that different patients present with different risk factors and that a sensible approach should consider different targets based on the population. For example, in samples with a high number of smokers a much lower target could be considered as it is more important to focus on smoking cessation in the first instance and maybe introduce dietary advice at a later stage.

Furthermore, as a prospective audit the data may have been skewed as a result of the Hawthorne Effect, whereby the behaviour of the participating clinicians may have only changed as a result of being observed. In the long term, re-audit/future retrospective audits may overcome this limitation.

It is of the authors' view that incorporating dietary advice, as part of periodontal prevention, should be a team-based approach. The results from this audit did show that the advice was given fairly evenly between dentists and hygienists/therapists, although it must be considered that more dentists were involved in the audit and the figures shown are a reflection of diet advice provided by the entire team. Individual data is available for each participating dental care professional (DCP), but this audit took a more practice-based approach to the delivery of dietary advice and therefore the data collected has been presented as a whole. It is also of the authors' view that DCPs are central to providing dietary advice particularly in light of the regular contact that they have with patients who are placed on a periodontal maintenance regime. It could be considered that upon initial consultation and diagnosis of periodontitis, patients are informed and educated on the major risk factors such as smoking and poor oral hygiene rather than being overloaded with information on all possible risk factors. Following this, nutritional information could then be introduced to those who demonstrate the ability to control these major risk factors. In those patients who may not be exposed to such risk factors, introducing dietary advice at an earlier stage may be more appropriate.

It is anticipated that the audit cycle will be repeated at the practice within the next year at which point a new oral health educator will have been appointed who could provide the information in new ways. The practice website is currently being updated and on completion the written information will be placed online for patients to access. Further methods of communicating nutritional advice include presentations and displays in the patients' waiting area.

Finally, this audit has been directed at the role of the dental professional in providing dietary information. In order for the advice to be effective it must initiate a change in behaviour of our patients, something that was not investigated as it was outside the remit of this audit. A possible future direction may therefore be to investigate patient uptake of the information and ways in which the information can be provided to increase the likelihood of behaviour change, although these fall more under clinical research. This could include exploring the various models of health behaviour change.

Conclusion

To conclude, it should be noted that the risk factors for many general health conditions are common to those factors that affect oral health, namely smoking, alcohol misuse and a poor diet. It is therefore important that all clinical teams make every contact count and support patients to make healthier choices. As dental professionals we are in a prime position to see all patients, irrespective of their general health, at regular intervals to provide this support.

Commentary

An increasing body of evidence has identified a number of risk factors that modify the host response to bacterial challenge in the aetiology of chronic periodontal disease. These risk factors include behavioural or lifestyle factors (diet, exercise, smoking).

Nutrition is considered to be an important modifiable risk factor in the prevention and management of chronic periodontal disease, and may be capable of altering the host response to bacterial challenge. The Seventh European Workshop on Periodontology outlined dietary recommendations for the prevention and treatment of periodontal disease. These included increasing dietary fibre, fish oil, fruit and vegetables, and reducing intake of refined sugars.

This paper investigates the delivery of dietary advice by clinicians in a primary care setting in addition to the frequency, potential obstacles and the perception of barriers to the incorporation of nutrition, as part of periodontal therapy and prevention.

Following an initial retrospective pilot study to establish a suitable sample size and periodontal criteria, the sample size was set at 50 patients with a BPE criteria of 4 and/or * and BPE code 1-3 with evidence of historic or active periodontal disease. Participating clinicians (three dentists, one dental hygienist, one dental therapist) were given a brief explanation of nutrition advice relevant to periodontal health and informed of the audit.

Results from the first prospective study revealed 22% of patients received nutrition advice of which 100% was verbal, with an even balance in the delivery of information between the clinicians. An interview of the clinicians following the first cycle revealed a variation in knowledge surrounding periodontal health and nutrition; time constraints were considered an obstacle, over loading the patient with verbal information, and a lack of written information were also seen as barriers to delivering the information.

Following data collection from the first cycle, patient information leaflets were produced, reinforced by detailed information on nutrition advice given to all participating clinicians.

A second cycle was conducted which demonstrated significant improvement in delivery of advice. Sixty-eight percent of patients were given written advice supplemented by verbal explanation of the leaflet, with a consistent balance between clinicians.

This paper illustrates the willingness of clinicians to deliver nutrition advice following the provision of adequate training and the availability of written materials for the patient.

The authors acknowledge the possibility that the behaviour of the participating clinicians may have only changed as a result of being observed and recommend long-term re-audit/future retrospective audits to help overcome this limitation.

Juliette Reeves Dental Hygienist

Clinical Director of Perio-Nutrition, Number 18 Dental, Notting Hill London

Author questions and answers

Why did I undertake this research?

As an undergraduate I found myself interested in periodontology. Following attendance at the British Society of Periodontology conference in Autumn 2014 I was fortunate enough to listen to world leaders in their respective fields and was intrigued to learn more about how diet modulates inflammation. I realised that many dentists were not aware of this and following a literature review, decided to undertake the audit to raise awareness of this potentially important modifiable risk factor. Considering patient education forms the foundation of periodontal therapy, I focused on delivering dietary advice in primary care and ways to improve upon this. However, as this was the first audit of its kind I also wanted to understand how general dental practitioners perceived diet in relation to periodontal disease.

What would I like to do next in this area to follow on from this work?

Potential ways forward could involve re-audit to assess consistency in the delivery of dietary advice. Furthermore, getting involved with research groups that have an interest in how dietary components can down regulate the inflammatory pathways may open up the possibility of introducing personalised therapies in the future. Taking this project into a secondary care setting is also something that I would also like to follow on with. Finally, this audit only looked at the delivery of advice, and thus assessment of patient compliance would be the ultimate goal.

References

Adult Dental Health Survey 2009 - Summary report and thematic series. 2011. Available online at http://www.hscic.gov.uk/pubs/dentalsurveyfullreport09 (accessed October 2015).

Kassebaum N J, Bernabe E, Dahiya M, Bhandari B, Murray C J L, Marcenes W . Global burden of severe periodontitis in 1990–2010: A systematic review and metaregression. J Dent Res 2014; 93: 1045–1053.

Tonetti M S, Chapple I L, Periodontology WGoSEWo. Biological approaches to the development of novel periodontal therapies - consensus of the Seventh European Workshop on Periodontology. J Clin Periodontol 2011; 38(Suppl 11): 114–118.

Acknowledgements

This audit was funded by the British Society of Periodontology for which it received the BSP Audit Award 2015. I would also like to extend acknowledgement to the entire team at Walmley Dental Practice for their enthusiasm in taking part in the audit.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Raindi, D., Thornley, A. & Thornley, P. Explaining diet as a risk factor for periodontal disease in primary dental care. Br Dent J 219, 497–500 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.889

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.889