Abstract

The pressures on the dental team to successfully manage and treat periodontal diseases in general practice are ever-mounting. Dental practitioners have a duty of care to screen, investigate, diagnose, risk assess and appropriately treat periodontal diseases using evidence-based practice. Once patients are stable, they must continue to monitor and risk assess patients in the maintenance phase. Managing periodontal diseases in general practice is challenging and this has been reflected in the rising trend in periodontal litigation. General practitioners see the complete spectrum of patients; from those wanting to improve their oral health and are motivated to do so, to those who do not want to improve and are unmotivated. The Healthy Gums DO Matter toolkit, developed by Greater Manchester Local Professional Network for dentistry, provides a framework for dental teams on how to manage and treat periodontal diseases in general practice, providing a more pragmatic approach working under the current NHS dental contract. A care pathway model has been developed to manage both engaging and non-engaging patients, allowing for an increased focus on oral health education, patient motivation, personalised oral care plans and behaviour change techniques to achieve better outcomes for patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Key points

-

Highlights the responsibilities of dental teams in managing periodontal diseases.

-

Introduces the Healthy Gums DO Matter toolkit for managing periodontal diseases in general practice for engaging and non-engaging patients.

-

Discusses the importance of oral health education, patient motivation and behaviour change techniques for achieving periodontal stability in practice.

Introduction

The global burden of periodontal diseases has been steadily rising with periodontitis reported in over 50% of the population,1 and its severe form affecting around 11.2% of the global population, making it the world's sixth most prevalent disease.2 This is a trend we would expect to see in dentistry with an increasingly ageing population who are retaining their natural teeth for longer. The latest UK adult dental health survey showed that around 45% of dentate adults demonstrated pocketing over 4 mm, and this increased to approximately 61% in people aged 75 to 84 years.3

With the increasing prevalence of periodontitis, the pressures on the dental team to successfully manage and treat periodontal diseases are ever-mounting. Dental practitioners have a duty of care to screen, investigate, diagnose, risk assess and appropriately treat periodontal diseases using evidence-based practice. Once patients are stable, they must continue to monitor and risk assess patients in the maintenance phase. Dental teams must educate patients about the fundamental disease process and risk factors for periodontal diseases as well as motivate them to take ownership of their oral hygiene by providing tailored oral health education according to the patient's needs and ability, while also utilising behaviour change strategies. Finally, it is important that dental practitioners recognise their own limitations and make timely referrals for specialist care.

Managing periodontal diseases in general practice is challenging. General practitioners see the complete spectrum of patients; from those wanting to improve their oral health and are motivated to do so, to those who want to improve but are unable to do so, perhaps due to physical or mental impairment, to those who do not want to improve and are unmotivated. Each type of patient presents their own challenges, yet the duty of care remains the same. However, this does not necessarily mean a patient follows the same journey and our approach to treatment may vary with each type of patient. The challenge has been how to deliver this while fulfilling the legal and ethical duties of care. In addition to this, managing periodontal diseases is a lifelong process. Patients with periodontal disease may achieve stability or 'health', but they still remain at risk for developing further disease in the future and a patient in the maintenance phase is not necessarily the same as a patient in health.

These challenges have contributed to the rise in periodontal litigation that is currently being seen. Claims for dental negligence can be brought up to three years from the date of knowledge or awareness of the patient, not the date of negligence. As periodontal diseases span the lifetime of the patient, it remains open to litigation at any time. The consequences of this has been confirmed by Dental Protection who reported that undiagnosed and untreated periodontal disease is one of the fastest growing areas in dental litigation.4 The Dental Defence Union (DDU) has reported paying £2.8 million to settle 126 periodontal claims between 2008 and 2012,5 with 75% of these claims related to failing to diagnose and treat periodontal disease.6 The ultimate impact of this has been the increasing costs of professional indemnity insurance to practitioners.

Periodontal screening tools

Before discussing approaches to achieving periodontal health in patients, it is critical to highlight some important areas which form the basis of periodontal treatment and management. The first is to recognise that once a patient has been diagnosed with periodontitis, they are a periodontitis patient for life. The new classification system for periodontal diseases launched at Europerio 9 in 2018, for the first times classifies periodontal health.7 This was a crucial precursor in order to differentiate between patients who are periodontally healthy on an intact periodontium, and those who have periodontal health on a reduced periodontium due to previous periodontitis. While both patients are healthy, the latter has a significantly greater risk of developing periodontitis and further breakdown in the future. Therefore, this patient is now diagnosed as having periodontitis which is either stable, in remission or unstable.

This leads to a second important issue in the use of the basic periodontal examination (BPE). The BPE is designed to be a rapid screening tool. It can be used to differentiate between gingivitis and periodontitis, but it does not provide a definitive diagnosis, nor can it be used to assess the response to treatment in patients with periodontitis. Once a patient has been diagnosed with periodontitis, the detailed periodontal examination (DPC), or 'six-point pocket chart' is the primary tool to diagnose, assess the response to treatment and monitor periodontitis once a patient enters the maintenance phase. The new classification system will aid practitioners to correctly identify the appropriate method of probing for patients, as any patient with a history of periodontium breakdown due to periodontitis is now classified as having periodontitis and then diagnosed as either:7

Stable, with whole mouth bleeding on probing less than 10%, probing pocket depths of 4 mm or less with no 4 mm sites bleeding on probing

In remission, with whole mouth bleeding on probing greater than 10%, probing pocket depths of 4 mm or less with no 4 mm sites bleeding on probing

Unstable, with probing pocket depths of 5 mm or greater, or probing pocket depths of 4 mm or greater with bleeding on probing.

The DPC is the recommended probing and recording method for all three categories of patients. This has been reflected in the British Society of Periodontology's (BSP) guidance on the BPE where it states: 'For patients who have undergone initial therapy for periodontitis and who are now in the maintenance phase of care, then full probing depths throughout the entire dentition should be recorded at least annually'.8

Healthy Gums DO Matter

Greater Manchester Local Professional Network for dentistry recognised and discussed the challenges of managing periodontal diseases in primary dental care under the current NHS contract, and in 2014 initiated the Healthy Gums DO Matter (HGDM) project.9 The aim of the project was to produce a comprehensive resource to help dental teams to raise the standard of care for periodontal diseases and support them to achieve better patient outcomes. Having successfully launched the 'Baby teeth do matter toolkit', the decision was made to produce a new 'practitioner's toolkit' on how to manage periodontal diseases in dental practice.9

The toolkit was developed by a wide team including dental commissioners, dentists, a consultant in dental public health, specialists in periodontology, therapists, hygienists and dental care professionals. A care pathway model was used to manage patients with gingivitis, periodontitis and aggressive disease. A care pathway can be described as a tool for practitioners to help them streamline their decision-making process and align their treatment with recommended evidence-based best-practice.10,11 It aims to standardise care for a specific clinical problem using time or criteria-based progression to advance through the pathway.11 The care pathways developed in HGDM aimed to deliver a more pragmatic approach to managing periodontal diseases, while being more workable and realistic in general practice working under the current NHS dental contract. In addition to this, the toolkit has been risk-assessed and approved medico-legally by conforming to 'a standard of practice recognised as proper by a competent reasonable body of opinion'.12 Two supporting articles are included within the toolkit from a barrister specialising in dental litigation and a dental expert witness in periodontology.9

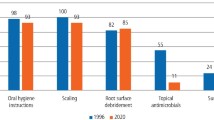

Figure 1 shows the potential effectiveness of the different stages of periodontal therapy and constituted the evidence base used to develop the HGDM care pathways.13 It can be seen from the figure that the largest reduction in the number of diseased sites was achieved post-oral hygiene instruction and initial therapy of scaling and correction of plaque retentive factors.

Here lies the key to achieving periodontal health in practice. Currently most of the remuneration in the NHS contract is for treatment, such as root surface debridement (RSD), with low incentives for prevention.14 However, the largest reduction in the number of pockets over 4 mm is seen after oral health education and behaviour change of the patient. Working within the current contract regulations, HGDM has tried to better support dental teams for the time invested in oral health education and behaviour change approaches, which will ultimately deliver better outcomes for patients.

This has been partly facilitated by delaying the start of formal periodontal therapy (DPC and RSD) until the patient has achieved adequate oral hygiene and plaque control. This allows more time and focus initially on oral health education, patient motivation, personalised oral care plans and behaviour change techniques. A number of useful resources have been developed as a part of the toolkit to support the dental team including:15

The patient agreement (a personalised oral hygiene plan for the patient which both parties agree to and sign)

The patient leaflet and consent form

Oral hygiene TIPPS (Talk, Instruct, Practise, Plan, Support), a simple behaviour change approach taken from the Scottish Clinical Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme's guidance on periodontal care.

The patient is then re-examined after three months to assess their response to the oral health education and 'patient engagement'. Here the concept of 'engaging' and 'non-engaging' patients has been developed to determine if patients will proceed onto formal periodontal therapy or remain in the oral health education, re-motivation and behaviour change phase if there is insufficient patient engagement. The evidence clearly shows that successful outcomes for periodontal therapy are best when supported with adequate self-care from the patient in maintaining adequate plaque control and oral hygiene.16 The most recent revision of the BSP's guidance document on BPE also reflects this where it states:

'The clinician should use their skill, knowledge and judgement when interpreting BPE scores, taking into account factors that may be unique to each patient. Deviation from these guidelines may be appropriate in individual cases, for example where there is a lack of patient engagement'.8

However, it should be noted that patients who are 'non-engaging' continue to receive treatment in the form of supra- and sub-gingival scaling (rather than RSD) to facilitate improvement in oral hygiene and plaque control.

Consequently, periodontal stability following treatment and root surface debridement will only be achieved if it is supported by adequate plaque control and patient engagement. The HGDM toolkit aims to deliver treatment when the patient is engaging for increased success of therapy. The focus before formal therapy (DPC and RSD) is undertaken is to educate and motivate patients to take ownership of their oral hygiene to prepare an optimal oral environment for the start of subsequent treatment.

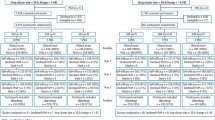

Patient engagement

The gold standard for assessing patient engagement is full mouth plaque and bleeding scores. However, this can be time consuming to undertake and is therefore underutilised in general practice. The new modified plaque and bleeding scores, based on Ramfjord's teeth,17 are quick and easy to use and offer a more consistent and robust method for assessing patient engagement, which were developed as a part of the HGDM toolkit. The new scoring systems, shown in Figure 2, use a partial mouth recording system using Ramfjord's teeth to record plaque and bleeding scores without the use of a disclosing agent, which was identified as a barrier by practitioners.18 In the HGDM pathways, the levels for an engaging patient have been agreed by the task group as less than 30% plaque score and 35% bleeding score or greater than 50% improvement in both, using the two new abbreviated indices. An engaging patient will continue onto formal periodontal therapy, whereas for a non-engaging patient formal therapy is delayed until there is sufficient engagement and they will remain in the oral health education, motivation and behaviour change phase of the pathway. While these values have been agreed in the HGDM toolkit, clinical discretion can be used, being flexible rather than rigid. A diagnostic study to determine the accuracy and validity of the modified plaque and bleeding scores in assessing patient engagement has been undertaken and the results of this study will be published in due course.19

a) The modified bleeding score; b) the modified plaque score.9 Reproduced with permission from Greater Manchester Local Professional Network for Dentistry, NHS England

The care pathways developed also aid practitioners in deciding when to refer for specialist care. While a patient can be referred for private specialist periodontal treatment at any time, the pathways have outlined a suggested referral point for NHS specialist periodontal care through the appropriate local referral system to level 2 and 3 specialist care providers. While it is ultimately the clinician's decision when they feel it is appropriate to refer a patient, the pathways have taken a reasonable and pragmatic approach to aid practitioners in referral for specialist care. An example of the care pathway for engaging and non-engaging patients for advanced periodontal disease (BPE scores of 4) is shown in Figure 3.9

An example of the care pathway for engaging and non-engaging patients for advanced periodontal disease9 (BPE scores of 4). Reproduced with the permission from Greater Manchester Local Professional Network for Dentistry, NHS England

Oral health education and behaviour change

The heart and soul of achieving periodontal health in practice lies in oral health education and changing and influencing the behaviour of patients, so that they achieve and maintain adequate plaque control and oral hygiene. As Figure 1 has shown, the largest reduction in disease sites was seen following oral hygiene instruction. However, while we communicate with patients daily, the question is how effective is that communication? Successful periodontal outcomes are dependent upon patient engagement and it is the patient who has to achieve daily high standards of plaque control. Of the 8,760 hours in a year, the patient is with the dental team for only a few hours or less. In this limited time, not only does all treatment have to be delivered, but also all the oral health education and motivational skills. It is therefore crucial that the way we communicate is not only efficient but also effective. Oral health education should be personalised to the patient, and the more personalised and relevant the message is to that individual, the greater the chance of engagement and success of periodontal treatment. The patient agreement shown in Supplementary Information 1 has been designed to aid the dental team with this personalised delivery and to support, but not to replace, human interaction.

Periodontal management is difficult because it requires a change in the behaviour of a patient. Behaviour change techniques and how to influence people are not taught in detail at undergraduate level and most practitioners learn as they progress through their career. It is important to understand and recognise that this is not an easy task to undertake and time is limited. Success requires building a trusting relationship with the patient in order for them to believe what they are being advised and to appreciate the benefits of changing their behaviour.

While there are a number of behaviour change approaches, from the simple oral hygiene TIPPS15 to the more advanced motivational interviewing techniques, one of the first steps in this process is to understand and recognise what exactly we are asking our patients to undertake. Achieving high levels of oral hygiene and plaque control can require considerable technical skill from the patient, as well as a significant amount of time. While the recommended messages for oral hygiene are popularly seen as brush for two minutes once or twice a day, this is for healthy patients. Patients with periodontitis can require up to 20 minutes once or ideally twice a day with oral hygiene procedures to achieve the high levels of plaque control and oral hygiene needed to achieve periodontal stability. It is essential that patients understand the time commitment needed on a daily basis to achieve this as well as planning how they will allocate this protected time. Twenty minutes for a cleaning session may seem excessive, but unless clinicians have themselves understood and appreciated the time commitment, only then can patients be educated correctly on what is expected from them. For example, a daily oral hygiene regime may include: brushing twice a day using a single tufted brush around the gum margins and between the teeth; interdental cleaning with the correct size interdental brush for each individual interdental space worked against both teeth from buccal, labial, lingual and palatal aspects; and then careful cleaning of furcation areas with single tufted and interdental brushes. At the start of the journey, this may even take the patient longer than 20 minutes as they learn to become more efficient. The patient needs to plan this time into their daily schedule and a part of the personalised care plan is empowering the patient with the knowledge, skills and motivation to intend to change, and then actually change their behaviour.

Conclusion

The HGDM toolkit provides a framework for managing periodontal diseases to support dental teams with the broad spectrum of patients they see and raise the standards of care in primary dental care. Achieving periodontal health in practice is challenging, but the toolkit has been developed to provide a more pragmatic approach to delivering care. While guidelines are fairly straightforward for engaging patients, the challenge has always been when and how guidelines can be departed from, with little guidance on when it is appropriate to use clinical discretion. The most recent revision of the BPE guidance by the BSP recognises that all patients are not the same and allows for deviation from the guidance. The HGDM framework is one approach on how to practically implement this in practice. The second edition of the HGDM toolkit will be released in 2019, having been updated to be in line with the new classification system and the BSP's implementation plan for clinical practice.

References

Tonetti M S, Chapple I L, Jepsen S, Sanz M. Primary and secondary prevention of periodontal and peri-implant diseases: Introduction to, and objectives of the 11th European Workshop on Periodontology consensus conference. J Clin Periodontol 2015; 42 (Spec Iss): S1-S4.

Kassebaum N J, Bernabé E, Dahiya M, Bhandari B, Murray C J, Marcenes W. Global burden of severe periodontitis in 1990-2010: a systematic review and meta-regression. J Dent Res 2014; 93: 1045-1053.

Steele J, O'Sullivan I. Executive Summary: Adult Dental Health Survey 2009. London: The Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2011. Available at https://files.digital.nhs.uk/publicationimport/pub01xxx/pub01086/adul-dent-heal-surv-summ-them-exec-2009-rep2.pdf (accessed August 2019).

Dental Protection. Periodontal Monitoring. 2014. Available at https://www.dentalprotection.org/new-zealand/publications-resources/clinical-audit-tools/clinical-audit-tools-display/2014/08/27/periodontal-monitoring (accessed August 2019).

Dentistry.co.uk. DDU pays out £2.8 million in compensation. 2014. Available at https://www.theddu.com/press-centre/press-releases/ddu-pays-out-2-million-to-compensate-patients-with-gum-disease (accessed August 2019).

Dental Defence Union. Surveillance. The Law and ethics of recording in dental surgeries. 2014. Available at https://www.theddu.com/-/media/files/ddu/publications/ddu%20journals/ddu%20journal%20march%202014.pdf (accessed August 2019).

Chapple I L, Mealey B L, Van Dyke T E et al. Periodontal health and gingival diseases and conditions on an intact and a reduced periodontium: Consensus report of workgroup 1 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Clin Periodontol 2018; 45 (Spec Iss): S68-S77.

British Society of Periodontology. Basic Periodontal Examination (BPE). 2019. Available at https://www.bsperio.org.uk/publications/downloads/115_090048_bsp-bpe-guidelines-2019.pdf (accessed August 2019).

Greater Manchester Local Dental Network. Healthy gums do matter! Periodontal management in primary dental care. Practitioner 's Toolkit. 2014.

De Bleser L, Depreitere R, WAELE K D, Vanhaecht K, Vlayen J, Sermeus W. Defining pathways. J Nurs Manag 2006; 14: 553-563.

Kinsman L, Rotter T, James E, Snow P, Willis J. What is a clinical pathway? Development of a definition to inform the debate. BMC Med 2010; 8: 31.

Bolam V Friern Hospital Management Committee. [1957] 1 WLR 582.

Chapple I L C, Gilbert A D. Understanding periodontal diseases: assessment and diagnostic procedures in practice. London: Quintessence Publishing, 2002.

Steele J S, Rooney E, Clark J, Wilson T. An independent review of NHS dental services in England. 2009. Available at http://www.sigwales.org/wp-content/uploads/dh_101180.pdf (accessed August 2019).

Scottish Dental Clinical Effectiveness Programme. Prevention and Treatment of Periodontal Diseases in Primary Care. 2014. Available at http://www.sdcep.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/SDCEP+Periodontal+Disease+Full+Guidance.pdf (accessed August 2019).

Lang N P, Tonetti M S. Periodontal risk assessment (PRA) for patients in supportive periodontal therapy (SPT). Oral Health Prev Dent 2003; 1: 7-16.

Ramfjord S P. Indices for prevalence and incidence of periodontal disease. J Periodontol 1959; 30: 51-59.

Moore D, Saleem S, Hawthorn E, Pealing R, Ashley M, Bridgman C. 'Healthy gums do matter': A case study of clinical leadership within primary dental care. Br Dent J 2015; 219: 255-259.

Saleem S. A diagnostic study to assess the accuracy and validity of two new abbreviated methods for scoring plaque and bleeding to assess patient engagement. Manchester: University of Manchester, 2017. MA Dissertation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Saleem, S. Seeking to achieve periodontal health in practice using the Healthy Gums DO Matter toolkit. Br Dent J 227, 629–634 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-0796-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-0796-3