Key Points

-

Emphasises the importance of dental function and access to dental care following treatment for head and neck (H&N) cancer.

-

Identifies the need for close collaboration between the primary dental services and the specialist H&N centres to optimise multidisciplinary support for patients.

-

Suggests that the use of checklist guided consultations assists patients in their post-treatment cancer journey.

Abstract

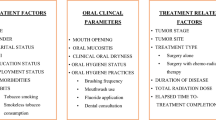

Background Patients experience considerable dental-related difficulties following head and neck cancer (HNC) treatment including problems with chewing, dry mouth, oral hygiene, appearance and self-esteem. These can go unrecognised in busy follow-up clinics. The Patient Concerns Inventory (PCI) is specifically for HNC patients, enabling them to select topics they wish to discuss and members of the multi-professional team they want to see.

Aim The study aimed to identify the clinical characteristics of patients raising dental concerns on the PCI and to explore the outcome of onward referral. Assessments included the PCI and the University of Washington Quality of Life Questionnaire (UW-QOL) version 4, with clinic details collated from hospital and cancer databases.

Method PCI data were obtained from 317 HNC patients between 2007 and 2011. Their mean age was 63 years and 60% were male. Most had oral squamous cell carcinoma and underwent surgery. The median (IQR) time from treatment to first PCI was 13 (4-42) months.

Results Three comparison groups were identified: patients with significant chewing problems, patients without significant chewing problems who wanted to discuss dental-related concerns and patients without significant chewing problems who did not want to discuss such concerns. Fifty-two percent reported either a significant chewing problem on the UW-QOL or a wish to discuss dental-related concerns. A quarter specifically asked to talk to a dental professional. Clinical characteristics significantly associated with dental issues were stage, primary treatment and free flap reconstruction. Clinic letters were copied to only 10% of general dental practitioners (GDPs).

Conclusion Better communication with GDPs is essential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

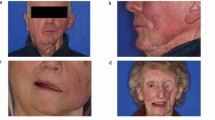

Chewing, masticatory function and dental health following the treatment of HNC is of considerable importance.1 Not only does the dentition have a positive impact on patients' health-related quality of life (HRQOL), self esteem2,3 and appearance, teeth have a social importance too.4 Patients requiring radiotherapy after surgery report much worse HRQOL than those having surgery alone.5 The main difference is in pain,6 saliva function and its impact on chewing.7 Xerostomia and trismus tend to be persistent side effects following radiotherapy and considerable care is required to maintain dental health.8,9,10 Furthermore, extractions in the field of radiotherapy may lead to osteoradionecrosis,10 which may in turn lead to segmental mandibulectomy and bony reconstruction.

The acute management of oral cancer and subsequent rehabilitation requires considerable multidisciplinary input from both the primary- and secondary care sectors to ensure patients receive the highest standard of care.11 This includes the patient's general dental practitioner (GDP), who, according to Fisher, refer 36% of oral cancers to secondary care.12 Their role includes surveillance13 and the provision of general dental treatment. The complex challenge of oral rehabilitation is sometimes a barrier to treatment and specialist referral is required.14

The priority that HNC patients place on dental issues and chewing is reflected in patient reported outcomes (PROMS). An example is the HRQOL questionnaire of the University of Washington in which patients consistently rank chewing as one of the top three items of importance.15 Also in the Patient Concerns Inventory (PCI), dental-related issues were ranked second to fear of recurrence, and are the most frequent issues patients want to discuss at their follow up consultation.16 The PCI has been shown to be a useful adjunct in clinics to help identify otherwise unmet needs,17 such as concerns of fear of recurrence,18 mood and anxiety,16 appearance related issues,19 and pain6. Thus far, dental-related concerns identified by the PCI in HNC clinics have not been investigated. Hence the aims of this study were to identify the clinical characteristics of those patients raising dental items on the PCI and to explore the outcome of onward referral.

Method

Prospective data collection from HNC patients attending routine follow-up clinics occurred between 1 August 2007 and 31 December 2011. Patients on the Liverpool oncology database were included if they were disease-free and under routine follow-up at least six weeks after completing treatment. Patients were excluded if they were before treatment, palliative, attending the clinic for other post-operative wound management or part of another clinical outcomes study. The study did not always coincide with the patients actual first visit to clinic following treatment completion as the cohort consisted of a convenience sample of patients returning routinely to attend their usual oncology follow-up visits.

Touch-screen technology (TST) was used by patients before consultation to complete the PCI and the University of Washington Quality of Life Questionnaire (UW-QOL). Following registration at clinic patients were invited by a hospital volunteer to complete the TST package. TST data was collected using Microsoft Access and placed directly on to a secure hospital server and was accessible to the clinician during the consultation. The PCI is a holistic, self-reported screening tool for unmet needs/concerns. It asks patients to select issues/concerns from a checklist that they would like to discuss during their consultation. Two of these concerns relate to chewing or dental issues – 'chewing/eating' and 'dental health/teeth'. Patients are also asked to select health professionals who they would 'like to see or be referred to' and options available include dentist, dental hygienist and oral rehabilitation team. Previous work on the PCI has allocated the PCI concerns four defined PCI domains which are used in the analysis.20

The UW-QOL questionnaire version 4 is well established21 and includes questions relating to 12 domains and a single six-point overall' QOL measure. The chewing domain is scored on a three-point scale as: (100) I can chew as well as ever, (50) I can eat soft solids but cannot chew some foods, (0) I cannot even chew soft solids. In earlier work23 we defined a significant problem' with chewing as being a UW-QOL domain score of '(0) I cannot even chew soft solids'. In regard to the single item overall QOL scale, patients were asked to consider not only physical and mental health, but also other factors, such as family, friends, spirituality or personal leisure activities important to their enjoyment of life.

Details of onward referrals regarding chewing and dental health arising from consultations were obtained from clinic letters. Clinical-demographic data came from the Liverpool HNC database.

Results were analysed mainly within three patient subgroups defined by reference to whether there was a significant chewing problem reported on the UW-QOL and to whether chewing/eating/dental-health/teeth issues were selected on the PCI. The chi-squared or Fishers exact test was used to compare subgroups in regard to patient and clinical characteristics, and health professionals selected from the PCI. There were many statistical tests performed and accordingly a stricter criteria p <0.01 has been used to represent statistical significance. Missing data is reflected in the slightly varying denominators. As the UW-QOL and PCI TST package is integrated into routine clinical practice in this setting, this study was approved by the University Hospital Aintree Clinical Audit Department in the context of audit/service evaluation.

Results

PCI data were obtained from 317 H&N patients attending 829 clinics on 132 different clinic days from 1 August 2007 to 31 December 2011. These patients had a mean (SD) age of 63 years (12) and 60% (191) were male. Primary diagnosis was squamous cell carcinoma for 85% (262/309). Tumour site was oral cavity for 70% (215/308), pharyngeal for 21% (66/308), and other H&N locations for 9% (27/308). Tumour TN stage was advanced T3-4 for 21% (63/297) and N positive for 22% (66/297). Primary treatment was surgery alone for 56% (168/299), surgery with adjuvant radiotherapy for 35% (105/299), and (chemo) radiotherapy alone for 9% (26/299). Of those treated with surgery, 53% (140/262) had free-flaps (110 soft, 30 composite). The median (IQR) time from primary surgery (or from primary diagnosis if no surgery) to first completion of the PCI was 13 (4-42) months, n = 304. UW-QOL data were available for 297 of the 317 patients at their first PCI clinic.

At the first study clinic 13% (40/297) could not even chew soft solids (Table 1), this being regarded as a significant chewing problem as measured by the UW-QOL (Group A). There were also 39% (115) without significant chewing problems who wanted to discuss chewing/eating/dental-health/teeth-related concerns (Group B) and 48% (142) without significant chewing problems who did not want such discussions. Notably only 58% (23/40) of those who could not even chew soft solids wanted such discussion, while 21% (22/103) of those who could chew as well as ever did want discussion. Overall, for 52% (155/297) there was either a significant chewing problem on the UW-QOL or a wish to discuss dental-related concerns. One quarter, 24% (76/317) wanted to talk with or be referred to a dentist (60), dental hygienist (15) or the oral rehab team (17). Overall, 57% (168/297) either had a significant problem with chewing, or wanted related discussion in the consultation or wanted to see a dentist, dental hygienist or the oral rehab team.

There was no significant association in relation to the three study groups by gender, age and time from primary diagnosis (Table 2). Patients with advanced clinical staging, oropharyngeal tumours, treatment by radiotherapy, free-flap surgery or worse overall UW-QOL reported more problems with chewing on the UW-QOL. There were no significant differences in patient and clinical characteristics in wanting or not wanting discussions in the absence of a significant chewing problem (that is, between groups B and C, Table 2) apart from overall UW-QOL where notably those with very good or outstanding QOL were least likely to want discussion. Patients with significant chewing problems (group A) were also the most likely to report other significant problems on the UW-QOL; notably appearance, swallowing, speech, taste, saliva, pain and anxiety (results not shown).

In regard to the number of PCI concerns overall, groups A and B raised considerably more issues to discuss than group C, the median (IQR) total being 6 (3-13), 6 (3-9) and 2 (1-5) respectively, p <0.001. The most common concerns raised by patients from the 3 groups are shown in Table 3.

With respect to choosing health professionals on the PCI the median (IQR) number chosen was 1 (0-2), 1 (0-1) and 0 (0-1) respectively, p <0.001. There were significant differences between groups in regard to selecting dentist, dental hygienist, oral rehabilitation team, and speech and language therapist (Table 4). About one third of patients with significant chewing problems (group A) selected 'dentist' from the list and also one third selected 'speech and language therapist' while one third of patients without significant chewing problems but wanting discussion (group B) also selected 'dentist'.

Clinic letters after consultation were analysed for 797 of the 829 clinics. Only in 10% (76/797) of letters was the dentist (GDP) copied in, predominantly to inform (64), otherwise to review (1), or to make a request (3), unknown for 8. The requests related to fluoride, tooth smoothing and surveillance. In 23% (181/797) the oral rehabilitation team was copied in, predominantly to inform (102), to make a request (47), to review (20), about prostheses (3), for assessment before radiotherapy (4), for extractions (1) or was not stated (4). The requests were in regard to review (30), prostheses (14), photographs (1), extractions (1) and information regarding CDS (1). Only once was a clinic letter copied in to a dental hygienist. The rates of letter copying for each of the three groups are shown in Table 5.

It was estimated that three quarters of clinic patients (74%, 511/693) still had (some) natural teeth; 48% (47/97) for group A, 77% (171/223) for group B and 79% (278/353) for group C, p <0.001. There was less information available about whether patients had a (high street) dentist at the time of clinic, 86% (276/322) overall; 58% (15/26) for group A, 88% (103/117) for group B, 88% (154/175) for group C, p <0.001.

Discussion

This study emphasises the importance of dental-related issues in HNC follow-up. Furthermore, the use of the PCI and HRQOL questionnaires in routine HNC clinics facilitates better post-op care by encouraging patients to raise concerns and provide the opportunity to refer to other members of the multidisciplinary team for further management. The patient's GDP is integral following treatment, and although some of the needs are complex, shared care between the primary and secondary services is ideal,14 as the dental needs of oral cancer patients are likely to increase with improved tooth retention, cancer survivorship and an ageing population.

The cohort was comprised mainly of oral cancer patients and it is reasonable to extend the findings to HNC in general as dental-related concerns are important in early or late oropharyngeal and laryngeal tumour sites.1 It was possible to retrieve and analyse most clinic letters, imaging and clinical correspondence by accessing electronic patient records. The only difficulty was in ascertaining the dental status of some patients where radiographs and comprehensive dental charting was absent.

Just over half the patients had either a significant chewing problem on the UW-QOL or a wish to discuss related PCI concerns. Patients with significant chewing problems reported worse overall quality of life. Furthermore, a quarter of all patients wanted to talk to or be referred to a dental healthcare professional, despite admittedly limited data suggesting 86% of all patients being known to have a dentist (though this was only 58% of the patients with a significant chewing problem). Encouraging patients with significant chewing problems to obtain a dentist should be a priority to improve shared care and perhaps their chewing problems. This is especially important, as access to dental services can be problematic.25

Patients with advanced clinical staging, who have undergone free flap surgery or radiotherapy tended to report more chewing-related problems on the UW-QOL. While there is evidence to support this trend,22,26 chewing difficulties will arise as a result of extensive surgical disruption to the masticatory apparatus. Duke et al. found that many effects of cancer treatment disappear between 12-36 months.26 However, following radiotherapy, good oral hygiene is essential to prevent radiation-induced caries and periodontal disease, so regular fluoride supplementation and periodontal therapy is necessary.

The data obtained indicated the correlation of significant problems across the UW-QOL (appearance, swallowing, speech, taste, saliva, pain, anxiety) with significant chewing problems. Evidence suggests that worse function is associated with higher levels of anxiety, depression and coping issues.27 Our data and evidence would suggest that improving physical function would prove significantly beneficial not only to physical parameters, but also to social-emotional parameters.

Significant chewing problems were found more commonly in the edentulous, and there is a role for oral rehabilitation in selected patients.28 Evidence demonstrates a psychological morbidity associated with those who don't receive oral rehabilitation.1 Furthermore, implant rehabilitation has shown to improve quality of life.29,30 Therefore, it would be prudent to consider all edentulous patients for oral rehabilitation to improve their functional and potential psychological morbidities.

The vast majority of clinical letters (96%) from the clinic were scrutinised and only in 10% of cases were GDPs included in correspondence. Interestingly, the patients with significant chewing problems had the least correspondence with the GDP (3%). Probably the commonest reason for the unit failing to correspond with the GDP is a deficit in recording the details of the GDP at initial referral and during at follow-up appointments. Communication difficulties have proven a problem for healthcare professionals involved in HNC care,31 with inadequate communication providing a barrier to the provision of dental care.32 What further complicates matters is that patients often visit their GP to report oral lesions.33 The patient's GDP has a clear role in surveillance for recurrence or second primary HNC. The management of oral cancer requires a variety of healthcare professionals and relies on effective communication between them. In this study, despite dental-related problems being highlighted in clinic, the correspondence to the patient's dentist was poor. This needs to be rectified and a protocol has been developed in the unit by which all patients are routinely asked about the details of their dentist, in the same way as they are for their doctor. A re-audit is planned to monitor improvements in correspondence to the patient's GDP.

References

Kanatas A, Ghazali N, Lowe D et al. Issues patients would like to discuss at their review consultation: variation by early and late stage oral, oropharyngeal and laryngeal subsites. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2013; 270: 1067–1074.

Rogers S N, McNally D, Mahmood M, Chan M, Humphris G M . The psychological response of the edentulous patient following primary surgery for oral cancer: A cross-sectional study. J Prosthet Dent 1999; 82: 317–321.

Pace-Balzan A, Rogers S N . Dental rehabilitation after surgery for oral cancer. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2012; 20: 109–113.

Linn E L . Social meanings of dental appearance. J Health Hum Behav 1966; 7: 289–295.

Bekiroglu F, Ghazali N, Laycock, R, Katre C, Lowe D, Rogers S N . Adjuvant radiotherapy and health-related quality of life of patients at intermediate risk of recurrence following primary surgery for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol 2011; 47: 967–973.

Rogers S N, Cleator A J, Lowe D, Ghazali N . Identifying pain-related concerns in routine follow up clinics following oral and oropharyngeal cancer. World J Clin Oncol 2012; 3: 116–125.

Rogers S N, Johnson I A, Lowe D . Xerostomia after treatment for oral and oropharyngeal cancer using the University of Washington saliva domain and a xerostomia-related qualityoflife scale. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010; 77: 16–23.

Dirix P, Nuyts S, Vander Poorten V, Delaere P, Van den Bogaert W . The influence of xerostomia on quality of life. Support Care Cancer 2008; 16: 171–179.

Kanatas A N, Rogers S N, Martin M V . A survey of antibiotic prescribing by maxillofacial consultants for dental extractions following radiotherapy to the oral cavity. Br Dent J 2002; 192: 157–160.

D'Souza J, Goru J, Goru S, Brown J S, Vaughan E D, Rogers S N . The influence of hyperbaric oxygen in the outcome of patients treated for osteoradionecrosis: 8 year study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007; 36: 783–787.

Moore S, Burke M C, Fenlon M R, Banerjee A . The role of the general dental practitioner in managing the oral care of head and neck oncology patients. Dent Update 2012; 39: 694–696.

Fisher S E . Delays in referral and treatment of oral cancer. Br Dent J 2000; 188: 258.

Gellrich N, Suarez-Cunqueiro M, Bremerich A, Schramm A . Characteristics of oral cancer in a central European population. J Am Dent Assoc 2003; 134: 307–314.

Husein A B, Butterworth C J, Ranka M S, Kwasnicki A, Rogers S N . A survey of general dental practitioners in the North West concerning the dental care of patients following head and neck radiotherapy. Prim Dent Care 2011; 18: 59–65.

Rogers S N, Laher S H, Overend L, Lowe D . Importance-rating using the University of Washington Quality of Life questionnaire in patients treated by primary surgery for oral and oro-pharyngeal cancer. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2002; 30: 125–132.

Kanatas A, Ghazali N, Lowe D, Rogers S N . The identification of mood and anxiety concerns using the patients concerns inventory following head and neck cancer. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012; 41: 429–436.

Rogers S N, El Sheikha J, Lowe D . The development of a Patients Concerns Inventory (PCI) to help reveal patients concerns in the head and neck clinic. Oral Oncol 2009; 45: 555–561.

Ghazali N, Cadwallader E, Lowe D, Humphris G, Ozakinci G, Rogers S N . Fear of recurrence among head and neck cancer survivors: longitudinal trends. Psychooncology 2013; 22: 807–813.

Flexen J, Ghazali N, Lowe D, Rogers S N . Identifying appearance-related concerns in routine follow-up clinics following treatment for oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012; 50: 314–320.

Ghazali N, Roe B, Lowe D, Rogers SN . Uncovering patients agendas in routine head and neck oncology follow-up clinics: an exploratory study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2013; 51: 294300.

Laraway D C, Rogers S N . A structured review of journal articles reporting outcomes using the University of Washington Quality of Life Scale. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012; 50: 122–131.

Rogers S N, Lowe D, Yueh B, Weymuller E A . The Physical Function and Social-Emotional Function Subscales of the University of Washington Quality of Life Questionnaire. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010; 136: 352–357.

Rogers S N, Lowe D . Screening for dysfunction to promote multidisciplinary intervention by using the University of Washington Quality of Life Questionnaire. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2009; 135: 369–375.

Rogers S N, O'Donnell J P, Williams-Hewitt S, Christensen J C, Lowe D . Health-related quality of life measured by the UWQoL reference values from a general dental practice. Oral Oncol 2006; 42: 281–287.

McGrath C, Bedi R, Dhawan N . Who has difficulty in registering with an NHS dentist? – A national survey. Br Dent J 2001; 191: 682–685.

Duke R L, Campbell B H, Indresano A T, Eaton D J, Marbell A M, Myers K B, Layde P M . Dental status and Quality of Life in Long-Term Head and Neck Cancer Survivors. Laryngoscope 2005; 115: 678–683.

Hassanein K, Musgrove B, Bradbury E . Functional status of patiens with oral cancer and its relation to style of coping, social support and psychological status. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2001; 39: 340–345.

Rogers S N, Panasar J, Pritchard K, Lowe D, Howell R, Cawood J I . Survey of oral rehabilitation in a consecutive series of 130 patients treated by primary resection for oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005; 43: 23–30.

Schoen P J, Raghoebar G M, Bouma J et al. Prosthodontic rehabilitation of oral function in head-neck cancer patients with dental implants placed simultaneously during ablative tumour surgery: an assessment of treatment outcomes and quality of life. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008; 37: 8–16.

Awad M A, Locker D, Korner-Bitensky N, Feine J S . Measuring the Effect of Intra-oral Implant Rehabilitation on Health-related Quality of Life in a randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J Dent Res 2000; 79: 1659–1663.

Edwards D . Head and neck cancer services: views of patients, their families and professionals. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1998; 36: 99–102.

Patel Y, Bahlhorn H, Zafar S, Zwetchkenbaum S, Eisbruch A, Murdoch-Kinch C A . Survey of Michigan dentists and radiation oncologists on oral care of patiens undergoing head and neck radiation therapy. J Mich Dent Assoc 2012; 7: 34–45.

Carter L M, Ogden G R . Oral cancer awareness of general medical and general dental practitioners. Br Dent J 2007; 203: 248–249.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mahmood, R., Butterworth, C., Lowe, D. et al. Characteristics and referral of head and neck cancer patients who report chewing and dental issues on the Patient Concerns Inventory. Br Dent J 216, E25 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.453

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.453

This article is cited by

-

An audit of dental assessments including orthopantomography and timing of dental extractions before radiotherapy for head and neck cancer

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

The Patient Concerns Inventory in head and neck oncology: a structured review of its development, validation and clinical implications

European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology (2022)

-

The impact of pre-radiotherapy dental extractions on head and neck cancer patients: a qualitative study

British Dental Journal (2018)

-

Estimation of Expression of Oral Fluid Biomarkers in the Diagnosis of Pretumor Diseases of Oral Mucosa

Bulletin of Experimental Biology and Medicine (2017)

-

Trends in the 15D health-related quality of life over the first year following diagnosis of head and neck cancer

European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology (2016)