Key Points

-

Highlights shortfalls in communication between referring GDPs and secondary care.

-

Suggests referral communications from GDPs can be improved by designing a proforma in accordance with gold standards.

-

Shows the use of a guidance letter to GDPs has reduced incorrect, incomplete or inappropriate referral letters.

Abstract

Introduction General referral letters to any hospital specialty are universally poor. These letters are the main source of information regarding the clinical problem and shortfalls can compromise the management of the patient.

Method One hundred retrospective randomly selected oral surgery referral letters in the form of proformae, made to oral and maxillofacial departments were examined against a set standard. Following the audit, a redesigned proforma, guidance and feedback questionnaires were distributed, followed by re-audit of 100 redesigned referral proformae.

Results The main improvements seen were increases of: 52% in stating type of anaesthesia, 48% medical history, 38% referral date, 35% duration of symptoms, 32% use of the 'clinical details section', 31% stating treatment provided, 23% symptoms, 21% in clarity, 18% general medical practioner's (GMP's) address, 18% reason for referral, 15% social history, 14% diagnosis, 13% in using diagrams to aid explanation and 10% inclusion of a radiograph.

Discussion Improvements in the quality of referral communications from local dentists were successfully made.

Conclusion Designing a pro-forma in close accordance with gold standards can achieve notable improvements to allow us to provide the best possible service and management for all our patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

General referral letters to any hospital speciality are universally poor.1,2,3,4,5,6,7 These letters are the main source of communication between the referrers and secondary care regarding the clinical problem.8,9 Shortfalls in providing sufficient, clear and relevant information can therefore delay or compromise the efficient management and triaging of the patient.5,10 In order to offer patients the best possible care, it is important to communicate as much background information as possible via the referral letter before the first consultation.5,11,12 Medical history and diagnosis appear to be most commonly omitted from the referral letter.1,4,5,13

Currently, there are no set guidelines for what an oral surgery referral letter or that of another dental specialty should contain. This may explain why many general dental practitioners omit necessary details in their referral letters. Nevertheless, recommendations have been made by numerous publications5,8,9,12,14 and most hospitals tend to have their own trust guidelines on dental referrals.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the use of a standardised referral proforma results in an increase in the provision and quality of information by practitioners referring to a dental hospital.1,3

Since a high number of inadequate referral letters present to the Oral and Maxillofacial Department at The Homerton University Hospital, the authors carried out an audit to assess the quality of information given on the department's current referral proforma, highlighting the areas where shortfalls occur and how this could be improved.

Aim

The aim of the current study was to assess oral surgery referral letters, sent by GDPs to the oral and maxillofacial department, against a devised standard, in order to implement changes required for improving the current referral system.

Method

Since there are no set standards for oral surgery referral letters, we devised an evidence-based standard for the audit, based on several publications;1,2,3,15 the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guidelines16 and General Dental Council (GDC) guidelines.17 A 'gold standard' oral surgery referral letter would include all the information from the checklist in Figure 1.

One hundred retrospective and randomly selected oral surgery referral letters sent by GDPs to the department from January to May 2011 were examined and analysed against the gold standard. Any referrals for conditions other than oral surgery were excluded from the analysis.

Data were extracted, following comparison of each separate item in our standard above with the information completed on the referral proforma.

The data in conjunction with the design of the oral surgery proforma were reviewed to ascertain areas requiring improvement, in order to maximise future provision of information by referring practitioners. This formed the basis for implementing recommendations using an audit action plan. All effort was made to create a user friendly, concise and clear proforma. Thus, as a trial, a revised proforma, a guidance form and letter were distributed to 40 of our most common referring general dental practices. The aim was to increase the quality and quantity of essential information to be captured.

A random sample of 100 new redesigned proformae received from referring GDPs were collected, re-analysed and re-audited, against the same standards as shown in Figure 1. The data of the re-audit were compared with the initial audit data.

Results

Initial audit

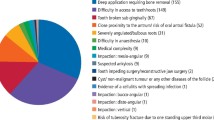

For the purpose of identifying items on the proforma that were poorly completed, we used the arbitrary value of 5% as margin for error. Based on this margin of error we identified the necessity to improve the provision of the following information, in consecutive order of more frequently excluded from the referral letters: requirement for interpreter, general anaesthetic or local anaesthetic requirements, inclusion of radiographs, stating urgency with an explanation, duration of symptoms, treatment already provided, smoking/alcohol habits, general medical practioner's (GMP's) telephone number, date of referral, symptoms, medical and drug history, using diagram to aid explanation, stating GMP's address, use of the clinical details section of the proforma, stating diagnosis, patient gender, GMP name, reason for referral, clarity of the referral letter, stating GDP's and patient's telephone numbers.

Re-audit with the revised proforma

The same 5% margin of error was re-utilised for the purposes of highlighting any significant differences in data between the initial and re-audit. The provision of information by referring GDPs has shown substantial improvements when compared with the initial audit (see Fig. 2).

There was deterioration of 16% in provision of GDPs' telephone numbers, compared with our initial audit, caused by our regular GDP referrers knowing that their full contact details are already on our database.

Discussion

This study highlights where shortfalls in providing essential information occur and that there is a need for a significant improvement in the provision of essential information by referring GDPs.

The rationale behind the revised proforma after our initial audit was as follows:

-

The date of referral was absent in over half of the completed initial referral proformae, despite its importance. This was accommodated for at the beginning of our revised proforma, to avoid its neglect

-

Almost half of the referral proformae (49%) failed to include GMP details. This may be caused by lack of GMP details from the patients and GDPs assumption that this will have no impact on the referral. GMP details are vital for the referral to be accepted by the hospital as this is the source of funding for treating these patients in secondary care. Thus, omitting GMP details may result in the rejection of the referral

-

Disappointingly, only 42% of the referral proformae had details of medical or drug history, despite a separate section being provided on the proforma for these details. Medical history is crucial for efficient triage and correct prioritisation of the referral. Interestingly, a similar distribution of medical history inclusion in referral letters from GDPs and GMPs has been reported4,13

-

Seventy percent of referral proformae failed to note any details of smoking or alcohol. This may reflect the GDPs' perceived lack of importance of smoking. Emphasis should be made on postgraduate education in order to increase awareness, which has already been progressing successfully throughout the current UK dental undergraduate curriculum. The clinical details section was poorly completed. Only 40% of initial referral proformae had recorded details of the symptoms, 12% recorded duration of symptoms, 61% details of diagnosis and only 12% stated details of any treatment already received. The majority of the referrers animated a diagram printed on the proforma to aid their explanation. Only a minority used solely the diagram with no clinical details. This is unacceptable as it can cause confusion and may compromise patient care

-

Attempts at diagnosis was 61%, coinciding with Zakrewska's5 survey which demonstrated that over 50% of referral letters failed to make an attempt at diagnosis. However, Djemal et al.1 found a two-fold increase in diagnosis given when proformas were used

-

With clinical governance high on the agenda, and consideration to Ionising radiation (medical exposure) regulations 2000,18 it is important to ensure that patients are not unnecessarily exposed to radiation. The initial results revealed that 93% failed to include a radiograph. Similarly, only 7% of initial referral proformae stated the urgency justified with an explanation. This appears to be a fault within the culture of the referring GDPs, rather than the proforma itself, as it is clearly presented to prompt a justification

-

Nearly all (98%) the initial referral proformae failed to state whether treatment was requested under local or general anaesthetic. Where GA has been discussed with the patient by the referring practitioner, it is clearly stated in the GDC guidelines17 that the referring GDP is required to explain the risks associated with GA, discuss the alternative options and give a detailed medical history and clear justification for requesting GA in the letter of referral. Patel19 supports our findings and concludes that there is a lack of clear justification in the letters of referral for providing GA

-

The need for an interpreter had not been completed in almost all of the initial referral proformae (99%), despite the significant mixture of ethnic groups in the inner city of North East London. This could be attributed to the poor design of our initial proforma, which failed to include a section for interpreter/language. Many patients could not speak or understand English to a level that consent would be valid and therefore caused disruption or delays of clinics

-

In 27% of cases, there was no mention of the reason for referral due to the design of the initial proforma. The overall clarity of the referrals were good, however, a small proportion were difficult to read due to the use of lighter coloured pens or poor handwriting. Block capitals using a black pen is essential for efficient processing of the referral letter

-

The above points were considered in order to revise and improve the design of the proforma. Where the fault was with the referring practitioners, it was noted to create a guidance letter addressed to each referring practice. Following the distribution of a new and improved referral proforma, along with a guidance letter, our re-audit demonstrated that we have successfully improved the quality of referral communications from local GDPs. However, there is still room for further implementation to target individual referrers, who continue to send inadequate referral communications. The authors did not include GMPs in the audit as the vast majority of oral/dental referrals are from GDPs

-

Understandably, it can be tedious for a busy GDP to complete all the relevant information on a proforma, particularly when they receive no additional fee. However, this will avoid rejected referrals and unnecessary delay for the patients before receiving specialist consultation and treatment. Ultimately, in accordance with the GDC standards guidance17 the aim is to work in the best interest of the patient, which should be mutual.

Conclusions

This study has highlighted the shortfalls in communication between referring GDPs and our department in secondary care. Our audit cycle has demonstrated that the design of proforma in close accordance with gold standards can achieve further improvements. The distribution of a guidance letter on how to adequately complete a proforma with essential details has ensured fewer incorrect, incomplete or inappropriate referral letters being returned. This enhanced the quality of referral communications, prevents disruption in patient care, allowing us to provide the best possible service and increase patient satisfaction.

References

Djemal S, Chia M, Ubaya-Narayange T. Quality improvement of referrals to a department of restorative dentistry following the use of a referral proforma by referring dental practitioners. Br Dent J 2004; 197: 85–88.

White D A, Morris A J, Burgess L, Hamburger J, Hamburger R . Facilitators and barriers to improving the quality of referrals for potential oral cancer. Br Dent J 2004; 197: 537–540.

Snoad R J, Eaton K A, Furniss J S, Newman H N . Appraisal of a standardised periodontal referral proforma. Br Dent J 1999; 187: 42–46.

Chambers I, Scully C . Medical information from referral letters. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1987; 64: 674–676.

Zakrzewska J M . Referral letters-how to improve them. Br Dent J 1995; 178: 180–182.

Kourkouta S, Darbar U R . An audit of the quality and content of periodontal referrals and the effect of implementing referral criteria. Prim Dent Care 2006; 13: 99–106.

Izadi M, Gill D S, Naini F B . A study to assess the quality of information in referral letters to the orthodontic department at Kingston Hospital, Surrey. Prim Dent Care 2010; 17: 73–77.

McAndrew R, Potts A J, McAndrew M, Adam S . Opinions of dental consultants on the standard of referral letters in dentistry. Br Dent J 1997; 182: 22–25.

Hammond M, Evans D R, Rock W P . A study of letters between general practitioners and consultant orthodontists. Br Dent J 1996; 180: 259–263.

Webb J B, Khanna A . Can we rely on a general practitioner's referral letter to a skin lesion clinic to prioritize appointments and does it make a difference to the patient's prognosis? Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2006; 88: 40–45.

Westerman R F, Hull F M, Bezemer P D, Gort G . A study of communication between general practitioners and specialists. Br J Gen Prac 1990; 40: 445–449.

Newton J, Eccles M, Hutchinson A . Communication between general practitioners and consultants: what should their letters contain? BMJ 1992; 304: 821–824.

DeAngelis A F, Chambers I G, Hall G M . The accuracy of medical history information in referral letters. Aust Dent J 2010; 55: 188–192.

Senate of Dental Specialities. Good Practice in the dental specialties. London: The Royal College of Surgeons of England, 2004.

Mossey P, Holsgrove G, Davenport E, Stirrups D . Essential Skills for dentists. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Report on a recommended referral document. Publication 31. SIGN. 1998.

General Dental Council. Maintaining standards: guidance to dentists on professional and personal conduct. London: GDC, 1998.

Department of Health. The ionising radiation (medical exposure) regulations 2000. London: Crown Copyright, 2000. Online regulations available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2000/1059/pdfs/uksi_20001059_en.pdf (accessed September 2012).

Patel A M . Appropriate consent and referral for general anaesthesia - a survey in the Paediatric Day Care Unit, Barnsley DGH NHS Trust, South Yorkshire. Br Dent J 2004; 196: 275–277.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following members of the OMFS team at The Homerton University Hospital for their contribution to the audit: Dr Fenan Farid (clinical attachment) who helped with data collection for the initial audit, Dr Enamul Ali (Associate Specialist) for advice throughout the project and Mr Andrew Ezsias (Consultant) for advice about the design of the new proforma and guidance letter.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shaffie, N., Cheng, L. Improving the quality of oral surgery referrals. Br Dent J 213, 411–413 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.929

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.929

This article is cited by

-

The appropriateness of oral surgery referrals and treatment in contracted intermediate minor oral surgery practices in East Kent

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

Initial periodontal therapy before referring a patient: an audit

British Dental Journal (2019)

-

Referrals to a facial pain service

British Dental Journal (2016)