Key Points

-

This paper examines changes in investment in oral health (as measured by dental registration) during adolescence and offers explanation for such changes.

-

Identifies groups at risk of poorer oral health.

-

Provides greater insight into adolescent registration for dental services and prompts a review of the role of adolescent dental services.

Abstract

Background Studies investigating investment in health across the life course are lacking. The aim of this study was to examine investment in dental health across adolescence.

Methods Changes in dental health investment, as measured by dental registration (months) between when adolescents were aged 11/12 years compared to when they were 15/16-years-old, were investigated using ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions. Adolescents aged 11 or 12 years in April 2003 in the Northern Ireland Longitudinal Study were included (n = 13,564). The overall change in registration and changes according to socio-economic status, highest educational attainment of household reference person, parental marital status, as well as the individuals' gender and number of siblings were examined. Within variable disparities at both age groups were also investigated.

Results Average number of months registered with a dentist fell from 8.14 months (11/12 years old) to 7.38 months (15/16 years old) (p <0.001). No gender disparities existed when adolescents were aged 11/12 years but when adolescents were 15/16 years old, females had significantly higher registration than males (8.72 months:8.20 months; p <0.001).

Conclusions During the transition from childhood to adulthood, an individual's dental health may suffer as a result of a decline in registration rates with a dentist. This risk is likely to be greater among males than females. The role of children's services within dentistry should be reviewed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Grossman model provides a theoretical framework through which consumption of healthcare can be understood in terms of investments in human capital.1 The model provides useful insights into individual decision making, adapting a standard investment model. In this a role can be assigned to a range of variables including for example, ageing, through its relationship with depreciation of health, or education, in terms of the costs and returns from investments in health promoting behaviours. While the model has been deployed in a range of contexts,2,3 studies investigating investment in health across the life course are currently lacking. Adolescence is an especially important time in the life course as, while the stock of health generally remains high, it is at this juncture that individuals begin to assert autonomy in decision making, the impact of which can have potentially far reaching consequences.4 Within the context of the Grossman model, the transition from childhood to adulthood is likely to be accompanied by a change in the information set used to inform choices (reflecting differences in the accumulated life experiences of the decision maker between parent and child) and in the rate of time preference used to discount future health benefits. This may not only manifest itself in an overall reduction in health investments – a reduction in behaviours consistent with the consumption of preventive care for example – but in the emergence of differences between groups for whom parents may have acted as effective decision-making agents to a greater or lesser extent. With specific reference to oral health for example, a study conducted among 14-16-year-olds in Liverpool found more than half of the adolescents felt they were responsible for taking decisions regarding their dental attendance.5 With this increased responsibility, lower levels of dental attendance (what is also referred to as dental avoidance) were witnessed.6,7

In this paper we examine investment in dental health during adolescence as reflected by dental registration using administrative data for Northern Ireland on balanced panel data. Registration is used as this indicator since with the exception of self-care all other investments in oral health are conditional upon registration. Changes in registration rates related to adolescent gender, parental socio-economic status and education, marital status and family size are examined over time using multivariate techniques. Results are interpreted using an investment model of healthcare. This is to the best of our knowledge the first time that this issue has been examined.

Methods

Data

Data on adolescents aged 11 or 12 years in April 2003 in the Northern Ireland Longitudinal Study (NILS) were linked to monthly dental registration data available for the period April 2003 to March 2008. The NILS provides a data linkage between data from the census (demographics including socio-demographics) and vital statistics (births, deaths, marriages) on 28% of the Northern Ireland population and in order to ensure a sample was representative, sample members were chosen upon having one of 104 pre-designated birth dates. Details on the process and range of data linked are described extensively elsewhere.8 Individuals in the NILS are followed up longitudinally and information is available biannually on whether or not they are resident within Northern Ireland. As this study only had access to dental registration within Northern Ireland it was necessary to exclude those with missing data and those who left Northern Ireland during the study period; that is, those who were shown to have been missing at one of the biannual time points.

Variables

In Northern Ireland, community dental healthcare (with the exception of that delivered to special needs groups) is provided through the General Dental Service. This is a network of general dental practices reimbursed on a combination of capitation and fee for service basis. Utilisation of services is predicated on registration with a general dental practitioner (GDP) and all such registrations are captured by the Health and Social Care Business Services Organisation (BSO) who administer reimbursements. Under current rules, dental registration lapses for an individual if they have not attended the dentist for 15 months. Dental registration is therefore indicative of service utilisation at some time during that interval and allows access to the GDP system. A positive relationship between dental attendance and oral health has been observed elsewhere.9,10 Furthermore, NICE guidance recommends dental attendance every 3-12 months for patients less than 18-years-old,11 as frequent dental attendance provides dentists the opportunity to deliver and reinforce preventive advice and to promote the importance of good oral health. Hence, dental registration provides a valid, albeit imperfect, measure of investment in dental health. Dental registration (in months) was the dependent variable in this study. We hypothesised average dental registration would fall from when adolescents are 11/12 years old to when they are 15/16 years old. At younger ages, the parent is more likely to make decisions regarding their children's health than when adolescents are older and have more autonomy. Parents are likely to invest more in their children than the children would invest in themselves. This is firstly due to the fact that they have a greater information set upon which to draw with respect to the impact of poor oral health on later quality of life. Secondly, parents are likely to discount less heavily the future benefits and costs relative to those in the current period; again due to their relative position on the life course.

The 2001 census provides a range of variables linked through the NILS to the BSO data. Variables used in this study were: national statistics socio-economic classification (NS-SEC) of occupation, highest educational attainment for the household reference person (HRP – head of household), gender (male versus female) of the adolescent, parents' marital status and the number of siblings in the household. As the focus of this paper is on how these relationships may change across the adolescent years, the direct relationship between each of these variables and dental registration is not, in the interests of brevity, discussed here; the interested reader being referred to discussions elsewhere.12,13,14,15,16,17,18

One variable which is likely to display a time variant relationship is gender. We hypothesised a change in the relationship between gender and dental registration as adolescents aged. At younger ages (11/12 years old) the parent is likely to dominate decision making and is not likely to make a distinction between children based on gender. As the child ages and assumes more of the decision making role, we postulated females would be more likely to value access to care than males. This is perhaps a result of the greater pressure society places on females with respect to the aesthetic appearance of teeth. Therefore, as adolescents develop greater autonomy, a difference will emerge in registration patterns that reflect differences in the value placed on access to care between the genders.

Dental registration status (whether an individual was registered or not) with a general dental practitioner was available for all months within the 2003/04 and 2007/08 UK financial years except April 2003 and April 2007. Table 1 details the specification of each variable used.

The Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) obtained ethical approval for the creation of the NILS on 3 October 2007. For the purposes of this study, it was necessary to submit a 'notice of substantial amendment' to the Office for Research Ethics Committees Northern Ireland (ORECNI) to allow the merging of the NILS and dental data as a distinct linkage project. This project obtained clearance from ORECNI on 17 December 2008. Data within the NILS are anonymised and made available within a 'safe setting' at the headquarters of the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency.

Statistical methods

Changes in dental registration were investigated in several different ways. Firstly, separate multivariate ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions were conducted for average number of months registered in 2003/04 and 2007/08 (from a possible 11 in each year as April 2003 and April 2007 were missing) and this was carried out using a suitable reference category within each variable (as outlined in Table 1). As number of months registered is count data, it was also feasible to use count regression models such as poisson and negative binomial models which do not require the data to be normally distributed. However, with an increasing number of observations the dependent variable becomes approximately normally distributed under the central limit theorem making it feasible to use OLS regressions,19 as were used here.

Next, using the multivariate OLS regressions, changes in dental registration across the 2003/04–2007/08 period were examined using paired two tailed t-tests and this was done for the overall average number of months registered and also within each variable. White's test was used to test for heteroscedasticity in disturbance terms. In the presence of heteroscedasticity, robust standard errors were reported.

Results

Table 2 presents descriptive characteristics of the 13,564 adolescents in the sample. Approximately 30% of HRP were professional while over three quarters of HRP were educated to GCSE standard or below. Approximately half of the sample was male and half were female. Three quarters of adolescents were living in married families and approximately nine tenths had 1-3 siblings. As all socio-economic characteristics are drawn from the 2001 census, these do not exhibit variation over time.

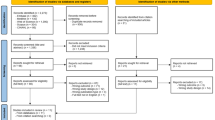

Table 2 also shows the results of the across-year analysis. It can be seen that average number of months registered with a dentist was, as hypothesised, significantly lower in 2007/08 when adolescents were 15/16 years old in comparison to 2003/04 when adolescents were 11/12 years old, (7.38 months compared to 8.14 months; p <0.001). Dental registration fell between 2003/04 and 2007/08 across all variables and differences were significant except among those living in cohabiting families and those with no siblings. As shown in Figure 1, the percentage of adolescents registered with a dentist decreased from 74.3% in April 2003 to 65.3% in March 2008. A clear divergence of male and female registration was evident; in April 2003 registration rates were 74.0% and 74.7% for males and females respectively but by March 2008, these rates had decreased to 63.1% for males and 67.7% for females.

Table 3 shows the results of multivariate analyses for 2003/04 and 2007/08. Results show dental registration varied according to household reference person NS-SEC and education, as well as by family type in 2003/04 and 2007/08. It can also be seen from Table 3 that while there was no difference between genders in dental registration when adolescents were 11/12 years old, females had significantly higher dental registration than males when aged 15/16 years (8.72 months compared to 8.20 months; p <0.001). A complex relationship was observed with respect to the relationship between registration and number of siblings. While those adolescents with one sibling exhibited higher dental registration at 11/12 years old, no relationships were witnessed when adolescents were 15/16 years old. Looking at registration as a dichotomous variable (not shown) revealed females were more likely than males to maintain registration across the entire time period examined with an increased odds ratio (and 95% confidence interval) of 1.13 (1.04, 1.23).

Discussion

This study has investigated investment as signalled by registration status in oral health across the adolescent years. Using data from the NILS and dental registration as a measure of investment in dental healthcare, an inverse relationship was identified between age and dental health investment. Inequalities which existed in relation to socio-economic status, parental education and family type remained consistent across the study period. We suggest this inverse relationship between age and dental health investment may be explained by factors relating to children developing more autonomy as they move through adolescence and their ability to influence their healthcare decisions to a greater extent. Differences may exist in the information set available to parents compared with adolescents and there may also be differences in the time preference applied by parents to children and those the children apply to themselves. Parents, we contend, are more likely to have suffered from poor oral health and therefore have a keener appreciation of the value of good oral health than their children. Similarly, as responsible agents, parents, we contend would and are shown to discount future benefits from healthcare investment less heavily than their children; behaviour that manifests itself in changes to registration rates.

It is unlikely the changes witnessed are due to exogenous factors relating to dental registration as dental registration for all children in Northern Ireland remained broadly constant across this time period.20 In addition to this, dental care is provided free of charge to all adolescents under 18 years of age, therefore study participants were entitled to free dental care throughout the study period.

This study also found that although no relationship existed between dental healthcare investment and gender when adolescents were 11/12 years old, by the time adolescents were aged 15/16 years females were more likely to be registered and to have maintained registration throughout the entire study period. This may be due to females deriving higher utility from oral health. Access to dental treatments associated with dental registration permits access not only to preventive, restorative and surgical treatment but also to treatments which can improve aesthetic appearance of teeth, such as orthodontics. Society places pressure on females to look attractive and hence females may derive higher utility from dental registration than males. It is worth noting though that this observed dental registration pattern may contribute to oral health inequalities besides those of aesthetic appearance in later life related to gender. In the 2003 children's dental health survey a higher percentage of 15-year-old boys reported oral problems compared to girls.21 While it would be unwise to extrapolate too far beyond this study, it is known that health inequalities related to gender extend beyond oral health. It is widely known, for instance, that men have shorter life-spans than women.22 Men are more likely to die from diseases such as cancer,23 which has been proven to be heavily influenced by potentially modifiable health behaviours such as diet, exercise and disease prevention (such as attending check-ups). This research would indicate risk taking health behaviours, which are potentially modifiable and are being undertaken as early as adolescence. Inequalities in oral health are part of a broader pattern related to gender that are the subject of ongoing study and policy review.

One way of tackling the witnessed decline in dental health investment across the adolescent years is to rebalance the relationship between costs and benefits associated with planning care, such as providing aspects of dental care through the school system. Such a system is currently delivered in the Republic of Ireland.24 If adolescents are relieved of the burden of arranging appointments (and do not have to sacrifice leisure time to attend a dentist), they may be more likely to access care. This may also help to overcome the gender disparity as while the cost of care may not differ between genders, currently the magnitude of these relative to the perceived benefits of care would appear to. Reducing non-monetary costs may, in other words, have a disproportionate impact upon males. In the past within Northern Ireland, dental screening was carried out by the Community Dental Service on primary school children but this ceased in 2007/08 as research undertaken by the University of Manchester concluded only a small proportion of children identified as in need of treatment went on to receive treatment. Therefore, it is important to provide treatment alongside such in-school screening. It may also be that dentists have a direct role to play in preventing this decline in dental health investment. Dentists may be able to offer advice specifically to their adolescent patients on the benefits of maintaining dental registration and hence encourage them to invest in their dental health as they become more autonomous in their lives. Whether or not this is the best way to address the issue remains to be seen but we would certainly advocate that the role of children's services in dentistry is reviewed.

Conclusion

Although this study benefits from a unique, highly detailed dataset, a limitation is that only dental registration with a general dental practitioner has been examined. It is also possible to obtain dental care from a community dentist in Northern Ireland or from a private provider. However, it is unlikely a high percentage of adolescents would obtain private dental care given the NHS provides free dental care to all adolescents under 18 years of age in Northern Ireland, or that any discrepancy here would explain the differences observed between groups or over time. Only a small number of adolescents within this study would have attended a community dentist and attendance with a community dentist would be of a more sporadic, symptom related nature rather than for regular check-ups. A further limitation is that we were unable to identify those who moved house during the study period as a separate group. In as much as this may impact on registration status we have no reason to suspect that this would be correlated with any of the variables in the study and therefore it is unlikely that the results are systematically biased.

In conclusion, this study has found investment in dental healthcare, reflected by dental registration, decreases as children move through adolescence, with this decline being more evident in males than females. This suggests that during the transition from childhood into adulthood an individuals' dental health may suffer, which is greatly concerning as caries in secondary dentition are often considered irreversible. It also suggests potentially modifiable risk-taking health behaviours, which are more likely to occur in males, are being undertaken from a young age.

References

Grossman M . The demand for health: a theoretical and empirical investigation. New York: Columbia University Press for the National Bureau of Economic Research, 1972.

Bolin K, Jacobson L, Lindgren B. The family as the health producer - when spouses act strategically. J Health Econ 2002; 21: 475–495.

Asano T, Shibata A . Risk and uncertainty in health investment. Eur J Health Econ 2011; 12: 79–85.

Miller P M, Plant M . Drinking, smoking, and illicit drug use among 15 and 16 year olds in the United Kingdom. Br Med J 1996; 313: 394–397.

Adekoya-Sofowora C A, Lee G T, Humphris G M . Needs for dental information of adolescents from an inner city area of Liverpool. Br Dent J 1996; 180: 339–343.

Hawley G M, Holloway P J, Davies R M . Documented dental attendance patterns during childhood and adolescence. Br Dent J 1996; 180: 145–148.

Nuttall N M, Bradnock G, White D, Morris J, Nunn J . Dental attendance in 1998 and implications for the future. Br Dent J 2001; 190: 177–182.

O'Reilly D, Rosato M, Catney G, Johnston F, Brolly M . Cohort description: The Northern Ireland Longitudinal Study (NILS). Int J Epidemiol 2011; [Epub ahead of print].

Donaldson A N, Everitt B, Newton T, Steele J, Sherriff M, Bower E . The effects of social class and dental attendance on oral health. J Dent Res 2008; 87: 60–64.

Telford C, Coulter I, Murray L . Exploring socioeconomic disparities in self-reported oral health among adolescents in California. J Am Dent Assoc 2011; 142: 70–78.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Dental recall- recall interval between routine dental examinations. NICE Clinical Guidelines 19. London: National Collaborating Centre for Acute Care, 2004.

Attwood D, West P, Blinkhorn A S . Factors associated with the dental visiting habits of adolescents in the west of Scotland. Community Dent Health 1993; 10: 365–373.

Hawley G M, Holloway P J . Factors affecting dental attendance among school leavers and young workers in Greater Manchester. Community Dent Health 1992; 9: 283–287.

Dey A N, Schiller J S, Tai D A . Summary health statistics for U. S. children: National Health Interview Survey, 2002. Vital Health Stat 2004; 10: 1–78.

Waldman H B, Perlman S P, Swerdloff M . Use of pediatric dental services in the 1990s: some continuing difficulties. ASDC J Dent Child 2000; 67: 59–63, 10.

Aday L A, Forthofer R N . A profile of black and Hispanic subgroups' access to dental care: findings from the National Health Interview Survey. J Public Health Dent 1992; 52: 210–215.

Yu S M, Bellamy H A, Schwalberg R H, Drum M A . Factors associated with the use of preventive dental and health services among U S. adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2001; 29: 395–405.

Dasanayake A P, Li Y, Wadhawan S, Kirk K, Bronstein J, Childers N K . Disparities in dental service utilization among Alabama Medicaid children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2002; 30: 369–376.

Rice J A . Mathematical statistics and data analysis. 3rd ed. India: Duxbury Press, 2006.

Department of Health, Social Services and Public Saftey. Dental Branch. Annual report 2007/ 2008. DHSSPS NI. Online report available at http://www.dhsspsni.gov.uk/dental-pubs (accessed March 2011).

Nuttall N, Harker R . The impact of oral health: children's dental health in the United Kingdom 2003. London: Office for National Statistics, 2004.

Mathers C D, Sadana R, Salomon J A, Murray C J, Lopez A D . Healthy life expectancy in 191 countries, 1999. Lancet 2001; 357: 1,685–1,691.

Office for National Statistics. Cancer incidence and mortality in the United Kingdom, 2005–2007. London: Office for National Statistics, 2010.

Irish Dental Association. Dental within the healthboards. Online information available at http://www.dentist.ie/resources/services/mcdentistry.jsp. (accessed March 2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was undertaken as part of a PhD funded by Queen's University Belfast. The help provided by the staff of the Northern Ireland Longitudinal Study (NILS) and NILS Research Support Unit is acknowledged. The NILS is funded by the Health and Social Care Research and Development Division of the Public Health Agency (HSC R&D Division) and NISRA. The NILS-RSU is funded by the ESRC and the Northern Ireland Government. The authors alone are responsible for the interpretation of the data. The authors would like to thank Professor Liam Murray of Queen's University Belfast for his support and input into this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Telford, C., O'Neill, C. Changes in dental health investment across the adolescent years. Br Dent J 212, E13 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.413

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.413

This article is cited by

-

A comparative examination of the role of need in the relationship between dental service use and socio-economic status across respondents with distinct needs using data from the Scottish Health Survey

BMC Public Health (2023)

-

Unlocking the potential of NHS primary care dental datasets

British Dental Journal (2022)

-

Summary of: Changes in dental health investment across the adolescent years

British Dental Journal (2012)