Abstract

Study design:

Clinimetric study.

Objectives:

To develop the Perceived Sexual Distress Scale (PSDS) in Hindi language (that is, PSDS-H) for persons with spinal cord injury (SCI), and to establish its content validity, internal consistency and test-retest reliability.

Setting:

New Delhi, India.

Methods:

Following a comprehensive literature review and semi-structured interviews, a 43-item questionnaire was drafted. Each item was rated on a 5-point scale. Content validity was established both qualitatively and quantitatively. Inter-item, item total correlations, internal consistency and test-retest reliability were calculated.

Results:

Expert panel opinion and content validity ratio (CVR) validated the content of the PSDS-H. Five items were dropped because of low CVR, resulting in a 38-item questionnaire. Internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.965. The test-retest reliability was 0.647.

Conclusion:

The PSDS-H is a valid, self/interviewer-rated tool that can help inform the rehabilitation team about the level of an individual’s perceived sexual distress post SCI. It also provides an outcome measure to evaluate the efficacy of interventions related to sexuality post injury.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The World Health Organization has described sexual health as ‘the integration of the somatic, emotional, intellectual and social aspects of sexual being in ways that are positively enriching and that enhance personality, communication and love’.1 Spinal cord injury (SCI) frequently concerns women and men in their sexually active and reproductive periods of life.2 In a study done by Reitz et al.2 on 120 persons with SCI, 63 reported that the major impact of SCI was on sexual functions. Consequences and complications of SCI, such as inability to move, neurogenic bladder and bowel dysfunction, spasticity and pain, all influence quality of life and sexuality.

Sexual readjustment after SCI depends greatly on the particular person’s wishes, experiences and sexual habits in their pre-SCI life. It may also, to a great extent, depend on the co-operation and helpfulness of the partner. The psychosexual functioning of persons with paraplegia is not different from quadriplegia.3 Sexuality and sensuality can be an expression of confidence, validation of the self and one’s perceived lovability. A review of the existing literature on sexuality and SCI explains the powerful influence of sexual problems and dysfunctions on psychology of the subjects, including issues of the affected body image, self concept, gender roles, general psychological health and basic sense of self-esteem.4, 5 These problems may give rise to sexuality-related distress in persons with SCI.6, 7

There is little available empirical research on the psychological distress experienced due to sexual dysfunctions post SCI. The available measures primarily examine physical aspects of sexual dysfunction, for example, Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI)8 and International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF).8 Limited knowledge on sexual functioning is not only due to paucity in research but also due to methodological shortcomings.9 Althof et al.,10 in his review study, has highlighted some omnibus sexual inventories that are heterogeneous, that is, they examine multiple domains of sexual function, knowledge and satisfaction. This includes the Deogatis Sexual Function Inventory (DSFI), Golombok-Rust Inventory of Sexual Satisfaction (GRISS), Changes in Sexual Function Questionnaire and Arizona Sexual Experience Scale. Moreover, the detection of treatment-related changes after any intervention was also difficult to assess using them.

Other measures such as The Sexual Satisfaction Scale for Women (SSS-W)11 and Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised (FSDS-R)12 are designed to measure the sexual satisfaction (in women) and the sexuality-related distress in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD), respectively. These scales cannot be applied to persons with SCI, as they are only applicable to females.

In summary, little research has examined the psychological component of distress experienced by persons following sexual dysfunctions post SCI. In particular, there is a need to develop a valid scale which would have the potential to gather documentable data, regarding the presence and the extent of SCI-related sexual distress. In contemporary clinical trials, the use of self-reported measures of sexual function, especially by diary, event log or self-administered questionnaires have become more widely relied upon. In particular, self-administered questionnaires have the advantage of providing a standardized, relatively cost-efficient assessment of past and current sexual capabilities at low patient burden that can be utilized in international multi-institutional and multi-cultural studies. As persons with higher SCI lesions may not be able to express their opinion on the scale by writing, the option of interviewer administration should be made available for this subgroup. Keeping these issues in mind, the study aimed to develop a measure to assess the perceived distress due to sexual dysfunction is persons with SCI, in Hindi language.

Materials and methods

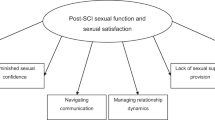

The study was a clinimetric research design study conducted at Indian Spinal Injuries Center, New Delhi, India. The development of the Perceived Sexual Distress Scale in Hindi (PSDS-H) was done in three phases as given in flowchart (Figure 1).

Phase 1: Development of scale

Articles were searched online using the keywords ‘spinal cord injury and sexuality’, ‘sexuality post SCI’, ‘psychological effects of sexual dysfunction in SCI’, ‘sexual distress in SCI’, ‘psychosexual functions in paraplegia and quadriplegia’, ‘sexual functions in complete and incomplete SCI’ and ‘importance of sexuality in persons with SCI’. Primary attention was given to the journals which had articles related to SCI and sexuality, altered sexuality, sexual dysfunction, sexual dissatisfaction, sexual need and psychological effects of sexual dysfunctions in SCI, for example, ‘Spinal Cord’, ‘Journal Of Spinal Cord Injury’, ‘Archives Of Physical Medicine And Rehabilitation’, ‘Sexuality And Disability’, ‘Journal Of Spinal Cord Medicine’, ‘International Journal Of Impotence Research’ and many more. Few other journals not directly related to the physical effects following SCI but having literature on the behavioral and psychosexual health and effects in SCI were also selected, for example, Journal of Behavioural Sciences, American Journal of Occupational Therapy, Urology and so on. Over 50 articles were reviewed thoroughly. The details of the methods these studies followed to collect their data were also reviewed. Other literature was obtained through the use of online search engines such as Google and Yahoo. The database search was done by one investigator, followed by inputs from the second investigator for improvisation and better search, and selection of the journals and the articles. Also books available on SCI, sexuality and disability, paraplegia and quadriplegia, rehabilitation and so on were reviewed. Following the review, basic themes were derived out of them by the researchers.

The semi-structured interviews of the focus group (persons with SCI) were then conducted by the same researcher via open-ended set of 15 questions pertaining to distress due to sexual dysfunction and the subjective feelings of the individuals. In total, 15 persons with SCI (13 males and 2 females) in the age group of 21–45 years, 11 married and 4 single, were interviewed. Their responses were either noted down or audio-taped depending upon the respondent’s choice and functional level (American spinal injury association), to ensure their comfort. Themes were then generated from the interviewed data. These themes were merged with the data generated from the initial review of the literature. The merged themes were then discussed and finalized by the researchers. The following steps, as described by Lynn’s ‘stage I—development stage’13 were followed:

Identification of domain of content

The major domains identified were:

-

a)

Individual-related domain: Sixteen statements, all of which, in some or the other form, presented individual-related distressing feelings which covered biological, emotional and psychological components of life of a person with SCI.

-

b)

Partner-related domain: with two sub-domains (Part I—Coupled Individuals and Part II—Single Individuals) for the different relationship status of the persons with SCI, and hence the different perceived sexual distress in both the groups. This domain was related to issues such as sexual satisfaction of partner, fear of the relationship ending, alternative sexual posture, adjustment problems and so on.

-

c)

Society-related domain: catered to the issues which incorporated myths related to sexuality in the society, social isolation, gender roles in society and so on.

-

d)

Guidance and rehabilitation-related domain: was related to the lack of proper guidance, hesitation of doctors and rehabilitation staff in catering to the sexual rehabilitation-related issues and so on.

Item generation

In total, 43 items were generated to assess each specific content domain.

Scale construction

The aim was to design a behavior instrument. The scale was chosen to be of ordinal kind (5-point, frequency type, self- and interviewer-rated).14 Respondents had to answer each statement in terms of how often the problem bothered them over the last 4 weeks. Typically, they were instructed to select one of five responses: ‘never, rarely, occasionally, frequently and always’. Higher scores indicated a more frequently occurring behavior, whereas lower scores indicated that the behavior occurred less frequently.15

Phase 2: Content validation and finalization of the ‘PSDS’

The following four phases were followed for establishing the content validity (McKenzie)16:

i. Creating an initial draft of the scale—(done in Phase I).

ii. Selecting a panel of reviewers to evaluate the scale.

Wallace et al.17 and Vogt et al.18 emphasized the necessity of relevant training, experience and qualification on the part of content experts, along with consultation with members of the target population (focus group), that is, those for whom the instrument is intended, to be critical and important during the multiple stages of instrument development. Thus, the final panelists were both:

(a) Experienced and qualified field experts comprising of one sexologist, one gynecologist, two clinical occupational therapists, one clinical physiotherapist, two senior occupational therapists, one senior physiotherapist, one rehabilitation psychologist and one peer counselor.

(b) Target group members comprising of 10 persons with SCI.

iii. Having experts conduct a qualitative review of the scale.

Experts were requested to provide their valuable feedback on the overall scale, the directions, scoring and the 43 items of the scale. They were asked to check and modify the order or flow of the items in each domain, and to identify and delete the theoretically incorrect items. Table 1 shows the outline of qualitative assessment criteria provided to all the experts. The experts’ comments were reviewed and appropriate changes were made.

Owing to the complexity of Hindi words in a few items (because those complex words were not in use in daily life by the common people), the expert panel suggested that the commonly used words to be written in parenthesis alongside the difficult words, so that the understandability of those items gets better. Such modifications were made for items 14, 19, 21, 22, 24, 25, 28, 37.

iv. Having experts conduct a quantitative review of the scale.

A panel of 20 subject matter experts were asked to indicate whether or not a measurement item in the set of all measurement items was ‘essential’, ‘useful but not essential’, ‘not necessary ‘. After receiving each expert’s ratings, content validity ratio (CVR) was calculated for each item.19 Of the 43 items, five items had to be dropped (CVR values of item numbers 9, 11, 13, 14 and 21 being 0.02, 0.02, 0.03, 0.04 and 0.01, respectively) resulting in a final 38-item scale with a score range from 0–152 (Sample items of the scale have been given in the appendix).

Phase 3: Field trial—internal consistency and test-retest reliability.

Thirty persons with SCI were purposively sampled, from both the in-patient and the out-patient departments of Indian Spinal Injuries Centre. The inclusion criteria were traumatic SCI, 18 years and above, with males and females being medically stable. The exclusion criteria were spinal shock, higher mental function disorder, homosexual orientation and diagnosed psychiatric illness. Withdrawal criteria were frustration and irritability on the part of the subjects, withdrawal of consent to participate in the study. American spinal injury association was scored to know the level and completeness of the injury, (Table 2). Since ‘sexual distress’ is an issue that might cause embarrassment, hence in order to reduce the response bias, interviews were taken in isolation or in the company of the spouse only, as was comfortable and desired by the person with SCI.

Depending upon the person’s functional status and wish, they were either given the scale to mark the desired options themselves or statements were read out and their respective opinions were taken. The scale was re-administered after a period of 1 week. SPSS 16 (VA, USA) was used for data analysis.

Statement of ethics

We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Results

Content validity: A minimum CVR value of 0.42 was necessary for statistical significance at P=0.05 based on 20 panelists.19 Out of 43 initial items, the item numbers 9, 11, 13, 14 and 21 had a CVR below 0.42 (at P=0.05), and hence were removed. These were the items that were related to the subjective feelings of sexual distress due to reduced happiness, preoccupation with sexuality-related thoughts, hopelessness, helplessness, and feeling of fatigue, respectively. The reasons for low CVR could not be explained but could be due to a number of reasons such as overlapping of those feelings with other items, or maybe those items were not being content specific. The remaining 38 items had sufficient to excellent CVR, including two items with CVR 1.0 at P=0.05.

Internal consistency reliability: Cronbach’s alpha for the overall scale was 0.965, which may indicate item redundancy.

Item total correlation: The coefficient ranged from 0.304–0.792, indicating that maximum items correlated with the total of the scale. Only one item (item number 29) did not show good correlation. A stepwise deletion of this item did not alter the internal consistency of the scale. Also, since this item was deemed important by the panel of experts, the item was retained in the final scale.

Inter-item correlation: Correlation coefficient ranged from 0.02–0.86.

Test-retest reliability

The ICC for the single measure of scale was found to be 0.647 (significant at 95% confidence interval) and for the average measure was found to be 0.785 (significant at 95% confidence interval).

Discussion

Previous research have concluded that sexuality outcome studies are notoriously difficult to design and conduct.10 Sexuality outcome studies need to assess the complex interplay between the biological, emotional, psychological and relational components of individual’s and couple’s life.10 Based on a comprehensive literature review, in addition to feedback from both professionals and focus group, a 38-item questionnaire, the PSDS-H was developed. This tool is quite practical, taking ∼20–25 min to administer; and is applicable across a wide-age range and for both the genders. The measurable data gathered by the PSDS-H can help the rehabilitation team to gain some insight regarding the effectiveness of interventions related to sexuality after SCI. As the scale is developed in Hindi language, a thorough understanding of the scale by the local people is ensured.

Limitations of the study

The subjects included in the study were from a single source, that is, Indian Spinal Injuries Centre (ISIC), thus the cultural and geographical variations might not have been considered in the study. Although the scale developed is able to assess the perceived sexual distress due to sexual dysfunction in persons with SCI, it will not differentiate between or identify the cause of sexual dysfunction. This scale is not valid for identifying the distress due to sexual dysfunction in homosexuals. During the field-testing phase, some persons with SCI self-administered the scale (paraplegics) and some were interviewer-administered (tetraplegics), owing to the limitation in hand functions. This could have led to a potential source of response bias, considering this to be a sensitive topic. The internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) was found to be very high, which might suggest item redundancy. The test-retest reliability (ICC 0.647) was slightly below standards.

Recommendations for future research

Since the issue of distress due to sexual dysfunction is subjective and is influenced by cultural and individual differences, the applicability of the scale to a larger group of persons with SCI and belonging to a variety of cultures is warranted. Also the possible use of this measure in other languages needs to be explored. Future research to remove possible item redundancy and to establish the criterion and construct-related validity of the PSDS-H is recommended. To ease the process of evaluation of clients via the PSDS-H, telephonic reliability of the PSDS-H could be established. Another promising mode of administration, in particular for persons with tetraplegia, would be to use a computer or a tablet with appropriate adaptations. Further studies can be done to explore the applicability of the PSDS-H to populations (other than SCI) with sexual dysfunctions, such as erectile dysfunction and infertility and so on.

DATA ARCHIVING

There were no data to deposit.

References

World Health Organization. Education and treatment in human sexuality: the training of health professionals: Geneva, 1975 (WHO Technical Report Series No. 572): 5-33.

Reitz A, Tobe V, Knapp PA, Schurch B . Impact of spinal cord injury on sexual health and quality of life. Int J Impot Res 2004; 16: 167–174.

Anderson KD . Targeting recovery: priorities of the spinal cord injured population. J Neurotrauma 2004; 21: 1371–1383.

Raghav SS . Sexuality and spinal injury. Ind J Neurotrauma 2009; 6: 91–92.

Stein SA, Bergman SB, Formal CS . Spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Individual experience, personal adaptation, and social perspectives. Arch Phys Med Rehab 1997; 78: S-65–S-72.

Susan B O’Sullivan, Thomas JS . Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. Physical Rehabilitation-Assessment and Treatment. Jaypee Brothers: New Delhi. 2001, 873–923.

Miller S . Sexual health care clinician in an acute SCI unit. Arch Phys Med Rehab 1981; 62: 315–320.

Alexander MS, Brackett NL, Bodner D, Eliott S, Jackson A, Sonksen J . Measurement of sexual functioning after spinal cord injury: preferred instruments. J Spinal Cord Med 2009; 32: 226–236.

Enzlin P, Mak R, Kittel F, Demyttenaere K . Sexual functioning in a population-based study of men aged 40-69 years: the good news. Int J Impot Res 2004; 16: 512–520.

Althof SE . Assessment of rapid ejaculation: review of new and existing measures. Curr Sexual Health Rep 2004; 1: 61–64.

Meston C, Trapuell P . Development and validation of a five-factor sexual satisfaction and distress scale foe women: The Sexual Satisfaction Scale for Women (SSS-W). J Sex Med 2005; 2: 66–81.

DeRogatis L, Clayton A, Lewis-D’Agostino D, Wunderlich G, Fu Y . Validation of the Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised for assessing distress in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sex Med 2008; 5: 357–364.

Lynn MR . Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs Res 1986; 35: 382–385.

Kothari CR . Research Methodology-Methods and Techniques. New Age International Publisher: New Delhi. 2004, 69–94.

Gliem JA, Gliem RR In:. Proceedings of Mid West Research to Practice Conference in Adult, Continuing and Community Education 8–10 October 2003; Columbus, OH. Ohio State University, USA.

McKenzie JF, Wood ML, Kotecki JE, Clark JK, Brey RA . Establishing content validity: using qualitative and quantitative steps. Am J Health Behav 1999; 23: 311–318.

Wallace LS, Blake GH, Parhem JS, Baldrige RE . Development and content validation of family practices residency recruitment quesstionnaires. Fam Med 2003; 35: 496–498.

Vogt DS, King DW, King LA . Focus groups in psychological assessment:enhancing content validity by consulting members of the target population. Psychol Assessment 2004; 16: 231–243.

Lawshe CH . A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers Psychol 1975; 28: 563–575.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the special support of Dr Chitra Kataria, Principal, ISIC Institute of Rehabilitation Sciences and Mr. A. Ramasamy, Assistant Professor, ISIC, N. Delhi.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Appendix

Sample items in English.

Individual related (total 16 items)

-

1

I am not satisfied with my sexual life.

-

2

Secondary problems related to stool and urine, stiffness, pressure sores, reduced sensations and so on increase my sexuality-related stress.

-

3

Due to sexuality-related problems, there has been a decrease in my self-confidence.

-

4

I feel depressed due to sexuality-related problems.

Partner related (total eight/eight items)

Answer either ‘Part 1’ or ‘Part 2’.

Part 1: couple (total eight items)

-

1

Due to sexuality-related problems, I am stressed about the sexual satisfaction of my partner.

-

2

Due to sexuality-related problems, I have fear of rejection by my partner.

-

3

I feel stressed in seeking co-operation from my partner for choosing alternate sexual position and making sexual relations.

Part 2: single (total eight items)

-

1

Due to sexuality-related problems, I am stressed about not being able to find future partner.

-

2

Due to sexuality-related problems, I might face adjustment problems with my future partner.

Society related (total seven items)

-

1

Due to my social roles and expectations, I have sexuality-related stress.

-

2

Due to sexuality-related problems, the societal attitude of isolation is increasing my stress.

-

3

The misconceptions and myths related to sexuality, prevailing in the society, have increased my stress.

Rehabilitation and guidance related (total seven items)

-

1

I feel stressed because of the hesitation of rehabilitation professionals in discussing sexuality-related issues.

-

2

I feel hurt due to the lack of sensitivity among the rehabilitation professionals and others toward sexuality-related issues.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Paneri, V., Aikat, R. Development of the ‘Perceived Sexual Distress Scale-Hindi’ for measuring sexual distress following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 52, 712–716 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2014.83

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2014.83