Abstract

Study design

Cross-sectional explorative observational study.

Title

Sexual satisfaction in people with spinal cord injury and their partners: an explorative study.

Objective

To investigate the determinants of sexual satisfaction among individuals with spinal cord injury and relative partners by assuming a bio-psycho-social perspective.

Setting

Online survey.

Methods

Thirty-eight individuals (22 individuals with SCI and their partners) were provided with an anonymous self-report questionnaire. Bio-psycho-social dimensions were investigated by using the Barthel Modified Index, Beck Depression Inventory-II, Short Form Health Survey (SF-36). Sexual attitudes of participants were assessed via the Multidimensional Sexual Self-Concept Questionnaire (Snell, 1993).

Results

While no differences were observed between individuals with SCI and their partners, women with SCI were overall more satisfied about their sexual life when compared to men with SCI. Coping strategies promoting self-efficacy and an active role in the sexual issues were predictive of Sexual Satisfaction in the couples of persons with SCI and their partners. No significant contribution was played by physical variables.

Conclusion

A tailored-made approach assessing the needs of both individuals with SCI and partners is a key aspect for effective sexual rehabilitation protocols. According to the needs and features of each couple, health professionals should drive individuals with SCI and partners to cope with their sexuality within a bio-psycho-social framework underlying it.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

People with a spinal cord injury experience a series of profound changes both on a physical level and on a psycho-social level [1, 2]. Although the recovery of sexual function has been acknowledged as a matter of great concern in individuals with SCI [1], this issue has been historically neglected when treating functional consequences after an SCI [3, 4].

In the past decades, sexuality treatment in individuals with SCI has been mostly approached by assuming a “biological” framework [3, 5, 6]. According to this approach, individuals with SCI would suffer from a sexual disability due to neurological dysfunctions preventing them from having sex according to the normal standard [7]. Only recently attention has been paid to this topic in both healthy and disabled persons by assuming a holistic approach to health—i.e., accounting for not only biological but also psycho-social variables [8, 9]. According to bio-psycho-social models, health arises from continuous and dynamic interactions between biological, psychological and social factors [10, 11]. Interestingly, yet in 1975, the World Health Organization [12] focused on a holistic approach to sexual health as a fundamental right to be guaranteed to all individuals, recognizing it as the experience of a continual state of physical, psychological, and sociocultural well-being in terms of sexuality [13, 14] More recently, Firestone et al. [15] defined sexuality in a broad sense, affirming that it “[…] encompasses all the feelings, attitudes, and behaviors that contribute to a person’s sense of being a man or a woman both publicly and privately. Healthy sexuality represents a natural extension of affection, tenderness, and companionship between two people”. Interestingly, this definition further emphasizes the experience of the intimate partner and thus the couple dimension.

A proper investigation of sexual health and satisfaction should thus go beyond the perspective of individuals with SCI, including also feelings and experiences of their sexual and emotional partners. With this respect, only few studies have explored the impact that SCI-related changes may have on the individual and her/his intimate partner [16,17,18,19]. These studies have nonetheless highlighted the relevance to sexual satisfaction of emotional well-being, body image and relationship with the partner besides physical functioning. Indeed, after an SCI, the decrease in personal autonomy and dependence on others in self-care can lead to changes in roles—this possibly altering the sexual dimension [20]. Given the relevance of sexual health within a couple, both individuals with SCI and their partners might experience a change in their general well-being [21, 22]. However, no study tried to explore how sexuality is experienced and perceived in a couple with an individual with SCI, and which factors can affect the levels of sexual satisfaction. This study thus aimed at exploring the determinants of sexual satisfaction in both persons with SCI and their respective intimate partners by addressing both physical and psycho-social predictors.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedure

Thirty couples were recruited in the north-east part of Italy from 2017 to 2018. Exclusion criteria for both individuals with SCI and their partners were other neurological pathologies, psychiatric and internal conditions. Questionnaires were distributed via e-mail and returned online (30–40’ completion time).

Response rate was 63.3% (38 out of 60). Twenty-four were individuals with SCI (9 females), and 16 partners (12 females) enrolled the study. Among those who did not answer the questionnaire, 19% were males and 7% females. Participants’ background and psychometric measures are displayed in Table 1. No economic incentive was provided for participations; responses were anonymous. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee (nr. 478/ORAS, 2018) of the local public Health System (ULSS 2 Treviso). All participants provided written informed consent to participation. Data were treated according to current regulations.

Materials

Following a bio-psycho-social approach, physical and psycho-social dimensions were self-reportedly explored along with sexuality (see Table 2).

Biological measures

Motor-functional outcome was assessed via the Barthel Modified Index (BMI) [23, 24]. The Italian BMI is internally consistent (Cronbach’s α = 0.94) and comes with optimal test-retest reliability evidence (ICC = 0.98) in clinical populations. Moreover, the BMI proved to be feasible in population with SCI, as optimally converging with the Functional Independence Measure (a gold-standard measure of ecological functional outcome) [25]. The Physical Functioning subscales of SF-36 (PF) [26,27,28] was also considered in order to evaluate physical measures. Within the Italia population, the PF shows optimal internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.93) and construct validity toward the General Health (GH) scale of the SF-36 [28].

Psycho-social measures

Depression levels were assessed through the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) [29, 30] and the psychological subscales of SF-36 (Vitality, VT; Role emotional, RE; Mental health, MH). Usability in individuals with SCI of both the BDI-II and SF-36 psychological subscales has been shown [31, 32]. The Italian BDI-II [30] shows optimal internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.8), convergent validity toward gold-standard measures of depression- and anxiety-related measures, a solid bi-factorial structure (RMSEA = 0.055; CFI = 0.92) and optimal diagnostic accuracy (AUC = 0.88). VT, RE and MH scales of the SF-36 show adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.78, 0.85 and 0.85, respectively) and construct/criterion validity toward the GH scale. [28].

Social functioning was assessed by the Social Function (SF) subscale of the SF-36. The SF scale show adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.77) and construct/criterion validity toward the GH scale [28].

Sexuality measures

Sexuality was investigated through the Multidimensional Sexual Self-Concept Questionnaire (MSSCQ) [33, 34]. MSSCQ is a self-report, Likert-item questionnaire measuring 20 facets of the sexual self-concept. Scores on each scale range from 5 to 25; high scores corresponding to higher levels of the construct. The original MSSCQ was translated into Italian. From the original questionnaire, two measured variables excluded were ruled out: Motivation to avoid risky sex (as we investigated sexuality in stable couples) and Sexual self-problem prevention (as it would have been difficult to disentangle general sexual self-problem prevention from issues deriving from SCI).

Sexual satisfaction was measured with the Sexual Satisfaction subscale of the MSSCQ [33, 34]. This subscale comprises five items—an example of which is “I am satisfied with the way my sexual needs are currently being met.” and showed optimal internal consistency in both females and males individuals (both Cronbach’s α = 0.91) within the original normative study [34].

Further ad hoc sexuality Likert-like measures were constructed in order to explore other variables more focused on SCI condition. Each variable was tested by means of two main questions once the participants completed MSSCQ. The subscales included:

-

Fertility: the importance of fertility in their sexual activity.

-

Other forms of sexuality: the importance of exploring other forms of sexuality apart from physical contact.

-

Satisfaction with the partner before and after the SCI.

-

Only for individuals with SCI: the decreasing of sexual intercourse after the SCI.

Statistical analyses

Normality and homoscedasticity assumptions were checked on raw variables by assessing skewness and kurtosis values (judged as indexing abnormalities if ≥|1| and |3|, respectively) [35].

Since sexual satisfaction was judged as meeting linear model assumptions, effects of Group, Sex and Length of Couple Relationship were simultaneously tested by means of a between-subject analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Consistently, in order to identify the best set of predictors of sexual satisfaction in individuals with SCI and Partner Group, stepwise multiple linear regression (MLR) analyses were performed separately for both groups. All motor-functional, psycho-social and (other) sexuality measures were entered as predictors in both MLRs, with the exception of Length of Couple Relationship (before vs. after the injury). Collinearity was inspected for by assessing variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance index (judged as abnormal if >10 and 0.1<, respectively) [36]. Analyses were performed via SPSS 27 [37]. Significance level was set at α = 0.5.

Results

Bio-psycho-social and sexuality measures of participants are summarized in Table 2.

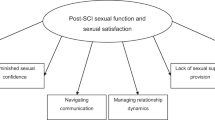

ANOVA revealed no main effects with the exception of Length of Couple Relationship (F(1,31) = 12.285; p = 0.001; η2 = 0.284): individuals who started a relationship after the injury (x̄ = 3.25; SE = 0.28) were more sexually satisfied than those who already had it before the event (x̄ = 2.16; SE = 0.12). Furthermore, a significant two-way Group*Sex interaction was detected (F(1,31) = 4.736; p = 0.037; η2 = 0.133) (see Fig. 1): its decomposition by means of post hoc, Bonferroni-adjusted comparisons showed that, within individuals with SCI only, sexual satisfaction was higher for females (x̄ = 3.29; SE = 0.33) than for males (x̄ = 2.25; SE = 0.27).

No other significant terms have been yielded.

Stepwise MLR for Partner Group proved that the best model (R2 = 0.82; F(2,11) = 25.54; p < 0.001) encompassed Sexual Depression (β = 0.62; t = −4.25; p = 0.001) and Chance/luck Sexual Control (β = −0.425; t = −2.92; p = 0.014). With regard to individuals with SCI, Sexual Self-efficacy (β = 0.829; t = 1.99; p < 0.001), decreasing of sexual intercourse after SCI (β = −0.34; t = −4.77; p < 0.001), years of education (β = 0.34; t = −5.51; p < 0.001), Satisfaction with partner before SCI (β = 0.26; t = 4.09; p = 0.001) and Sexual Fear/Apprehension (β = 0.26; t = 3.77; p = 0.002) proved to be the best set of predictors (R2 = 0.95; F(5,14) = 57.21; p < 0.001). In both models, no abnormal VIF/tolerance index was noted.

Given the theoretical juxtaposition between the constructs underlying Sexual Self-Efficacy and Chance/Luck Sexual Control [33], their association was further explored in the two groups via Spearman’s coefficient (due to small sample sizes). No association was found between Sexual Self-Efficacy and Chance/Luck Sexual Control in Partner Group (rs(16) = −0.44; p = 0.086), where the two variables were inversely correlated in individuals with SCI (rs(22) = −0.44; p = 0.038).

Discussions

Sexual satisfaction is a complex and dynamic experience that is subjected to physical, psychological and relational changes after an acquired SCI. While many attempts have been made to deal with sexual issues from the medical perspective, few research works tried to deepen the sexual issue by assuming a double perspective—that of individuals with SCI and relative partners. In this respect, the present work provides with preliminary evidence suggestive of different determinants affecting sexual health in individuals with SCI and their partners—although no differences were detected between-group in sexual satisfaction.

First, we found no differences in perceived sexual satisfaction between individuals with SCI and partners, while sex differences were detected—with females exhibiting higher levels of sexual satisfaction.

Second, in line with the literature [38, 39], couples formed after SCI showed higher levels of sexual satisfaction than couples formed before. It may be hypothesized that meeting the partner after SCI might allows establishing a de novo balance within the relationship, in which SCI is represented as a “normal” condition, rather than a modification of a previous one [39]. The couple would practice a wider range of habits during sexual practice without being compared to the previous condition, thus sharing new common future intercourses in which SCI does not determine a restorative couple but simply a factual reality on which a new relationship is being created [39, 40].

Interestingly, in both groups, no biological variables (i.e., associated to levels of motor dimension and functional independence) were found to affect sexual satisfaction when tested along with psycho-social predictors—this further endorsing that sexual health should be both clinically and experimentally addressed within a bio-psycho-social framework in disabilities [41,42,43]. However, it is worth noting that individuals with SCI participating to this research were recruited after at least 1-year pass the inpatient rehabilitation stage. In line with previous findings, since the biological dimensions and physiologically related sexual changes are usually a target priority of persons with SCI during the inpatient rehabilitation phase [20], it can be hypothesized that participants with SCI paid more attention to other variables than the biological ones given their ability to deal with them during the inpatient phase [20, 44].

By contrast, as suggested in the literature [45], the vast majority of sexual satisfaction determinants were mostly related to personal and sexual dimensions. However, strikingly, no overlap was found between the predictors of sexual satisfaction in individuals with SCI and their partners: while Chance/Luck Sexual Control was found to be predictive of sexual satisfaction in the partner group, Sexual Self-efficacy predicted sexual satisfaction for individuals with SCI. These findings suggest that different perspectives are adopted by individuals with SCI and their partners when dealing with sex-related issues and re-organizations of couple dynamics.

On the one hand, individuals with SCI seem to rely on a personal capacity of dealing with sexual issues depending on their condition. According to the literature, it has been demonstrated that individuals who are inclined to adopt active coping styles (e.g., believing they have a strong capacity to influence the direction of their lives [46, 47], knowing how to use different strategies in a flexible way [47, 48]) can achieve more positive ways of adapting to SCI [49,50,51]. Interestingly, as SCI is a clinical condition that globally affects an individual’s life, our data seem to highlight and confirm the importance of promoting the capacity of an active coping and adjustment when dealing with a SCI and sex-related practical issues to achieve high levels of sexual satisfaction [17]. Indeed, SCI has a profound impact on the body and its function [52], also being able to increase psychological distress impacting sexuality. Individuals with SCI find themselves experiencing a transition from a “known” body, in which every part of it was framed within a pattern, to an “unpredictable” body, which no longer reacts to the function of the former [48]. In this transition, a satisfactory level of sexual satisfaction would be reached by individuals with SCI when they become able to learn and develop a suitable capacity to recognize and manage the consequences of a SCI (i.e., bladder, bowel, spasticity, neuropathic pain, the inability to achieve reflex arousal and orgasm; [52]) affecting their sexuality. In this challenging process, health care professionals should pay attention to sexuality in order to help patients integrate different aspects of their body by specifically addressing the sexual dimension [17, 53,54,55]. In line with previous records, another predictive variable associated with satisfactory sexual life was the level of education of individuals with SCI [17]. First, higher levels of educational attainment might help individuals with SCI improve their problem-solving and self-efficacy thus leveraging their role in their sexuality (as discussed above); second, higher educational levels might promote more satisfactory social and occupational status—thus suggesting the importance of psycho-social inclusion after SCI when dealing with sexuality [17, 45].

The quality of a relationship was another key factor determining high levels of sexual satisfaction, highlighting the importance of considering such an issue not a personal one of individuals with SCI but rather something to share with the partner [17, 20]. As suggested by Lo Piccolo [56], the responsibility for sexual dysfunction must be shared, since intercourse takes place within the context of a pair relationship [57]. In this way, the optimal sexual functioning for the couple would depend on the willingness of both partners to take joint responsibility for an adequate sexual adjustment, playing together an active role in managing their sexuality.

Similar results were obtained for the partner group. Indeed, we found that lower levels of Chance/Luck sexual control were predictive of sexual satisfaction. In other words, in line with the literature [39], the more partners experience inclusion and responsibility in sexual life, the more satisfactory their sexual experience will be. Notably, the partner of an individual with SCI has been traditionally seen as the “caregiver”—with the dramatic consequences of such a perspective. Indeed, a switch from the role of an intimate partner may come with the risk of considering the disabled person more as a patient than as a partner [21, 58]. For partners, taking the role of a “passively” assisting caregiver who deal with motor impairments, bladder and bowel management without actively changing their condition, might greatly contribute to placing psychological barriers regarding the desire to resume a sexual life with one’s partner thus developing disappointment, anger, sadness and loss of intimacy [18, 58]. The physical limitations of the partner with SCI can also have a negative impact on the sexual desire of the non-disabled intimate partner. In addition, the partner may be afraid of having sexual intercourse with the partner with SCI, fearing that further injuries will occur during sexual intercourse [19, 59]. Thereupon, helping the partner develop emotional and physical closeness with the person with SCI, as well as to share and actively explore with her/him new forms of sexuality, can be a key predictive factor to reach a satisfactory sexual life [16, 19, 40].

Overall, in line with the literature, biological factors—such as the physical status and functional independence—did not significantly predict the perceived sexual satisfaction in the two groups, further suggesting the multidisciplinary determinants of this construct, going beyond a medical issue [17, 22, 45, 60].

Implications for sexual rehabilitation programs after spinal cord injury

According to our results, sexual rehabilitation programs for individuals with SCI and relative partners must go beyond biological aspects [61], broadening the intervention to factors focusing on the diversity and uniqueness of each individual living in their own reference psycho-social context [62, 63].

Indeed, individuals with SCI and partners must learn to redefine their concept of sexuality by adapting it to a new situation. In line with the results here reported, health professionals should drive individuals with SCI to “understand” their new body and learn to manage it within different contexts, including the sexual one. At the same time, health professionals should pay attention to the partners too, discouraging them to assume the role of caregiver when not necessary (i.e., related to the management of SCI issues), promoting the role of intimate partner as well. Sexual rehabilitation programs should thus help the couples adopt active adjustment processes, encouraging a shifting of the issue from “my problem” to “our problem” [64]. In this way, sexual health of the couple takes place from the willingness of both partners to take responsibility for sexual adjustment along bio-psycho-social dimensions as well [65].

Study limitations and future directions

Our study was culture-and language-specific (Northern part of Italy). Given the peculiar socio-political tradition and religious heritage of Italy, it would be insightful to examine how sexual satisfaction is perceived and experienced in individuals with SCI and their partners who come from cultures, religions, traditions other than Italian and, more broadly, Western ones. It is also worth noting that only heterosexual participants took part in the study, thus future investigation might explore the sexual satisfaction perceived in homosexual couples. Moreover, sexual satisfaction was explored in couples in which only one person has an SCI: how sexuality is perceived in couples in which both partners have an SCI might be addressed in future works.

A major limitation of this study was that the MSSCQ was adapted to Italian without any standardization process (i.e., back-translation). Therefore, an investigation is needed which focuses on the Italian adaptation of the MSSCQ, as well as on exploring its psychometric properties in an Italian population sample. In addition, bio-psycho-social dimensions were explored by using a specific corpus of instruments, but other questionnaires might help to better define the role of such dimensions underlying the sexual satisfaction.

In spite of the above limitations, our investigation emphasizes the importance of an active role played by both individuals with SCI and their partners in the quality of their sexual life. Starting from these findings, future investigation would attempt at improving tailored sexual rehabilitation programs during both the inpatient and the outpatient phases of rehabilitation for individuals with SCI and their partners, taking into account its medical and clinical condition, psychological status and socio-relational dynamics in the couple.

Data availability

The datasets collected and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Elliott S. Sexual dysfunction in women with spinal cord injury. In: Lin VW, editor. Spinal cord medicine: principles and practice. 2nd ed. New York, New York: Demos Medical Publishing; 2010. p. 429–37.

Elliott S. Sexual dysfunction in men with spinal cord injury. In: Lin VW, editor. Spinal cord medicine: principles and practice. 2nd ed. New York, New York: Demos Medical Publishing; 2010. p. 409–28.

Glenn E, Higgins JR. Sexual response in spinal cord injured adults: a review of the literature. Arch Sex Behav. 1979;8:173–96.

Comarr AE, Vigue M. Sexual counseling among male and female patients with spinal cord and/or cauda equina injury. Am J Phys Med. 1978;3:107–22.

Singh R, Sharma S. Sexuality and women with spinal cord injury. Sex Disabil. 2005;23:21–33.

Comarr AE, Vigue M. Sexual counseling among male and female patients with spinal cord and/or cauda equina injury: Part II. Am J Phys Med. 1978;5:215–27.

Thomson RG. Extraordinary bodies: figuring physical disability on America culture and literature. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1997.

Berry MD, Berry PD. Contemporary treatment of sexual dysfunction: reexamining the biopsychosocial model. J Sex Med. 2013;10:2627–43.

Elliott S, Hocaloski S, Carlson M. A multidisciplinary approach to sexual and fertility rehabilitation: the sexual rehabilitation framework. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabilitation. 2017;1:49–56.

Engel GL. The biopsychosocial model and the education of health professionals. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1978;310:169–81.

Schwartz GE. Testing the biopsychosocial model: the ultimate challenge facing behavioral medicine? J Consulting Clin Psychol. 1982;50:1040–53.

World Health Organization. Defining sexual health: Report of a Technical Consultation on Sexual Health. Geneva, Switzerland: Department of Reproductive Health and Research; 2002.

Larsen P, Miller-Kahn A, Ostrow FS. Sexuality. In: Lubkin IM, editor. Chronic illness impact and interventions. 4th ed. London: Jones Bartlett; 1996. p. 299–323.

Pangman VC, Seguire M. Sexuality and the chronically Ill older adult: a social justice issue. Sexuality Disabil. 2000;18:49–59.

Firestone RW, Firestone LA, Catlett J. What is healthy sexuality? In: Sex and love in intimate relationships. Washington DC US: American Psychology Association; 2006. p. 11–27.

Kreuter M. Spinal cord injury and partner relationships. Spinal Cord. 2000;38:2–6.

Reitz A, Tobe V, Knapp PA, Schurch B. Impact of spinal cord injury on sexual health and quality of life. Int J Impot Res. 2004;16:167–74.

Angel S, Buus N. The experience of being a partner to a spinal cord injured person: a phenomenological-hermeneutic study. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2011;4:1–11.

Taylan S, İlknur Özkan J, Küçükakça Çelik G. Experiences of patients and their partners with sexual problems after spinal cord injury: a phenomenological qualitative study. J Spinal Cord Med. 2020;45:245–53.

Fisher TL, Laud PW, Byfield MG, Brown TT, Hayat MJ, Fiedler IG. Sexual health after spinal cord injury: a longitudinal study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;89:1043–50.

Dickson A, O'Brien G, Ward R, Allan D, O'Carroll R. The impact of assuming the primary caregiver role following traumatic spinal cord injury: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of the spouse’s experience. Psychol Health. 2010;25:1101–20.

Federici S, Artegiani F, Pigliautile M, Antonelli P, Diotallevi D, Ritacco I, et al. Enhancing psychological sexual health of people with spinal cord injury and their partners in an Italian unipolar spinal unit: a pilot data study. Front Psychol. 2019;10:754.

Roth E, Davido G, Haughton J, Ardner M. Functional assessment in spinal cord injury: a comparison of the Modified Barthel Index and the ‘adapted’ functional independence measure. Clin Rehabil. 1990;4:277–85.

Galeoto G, Lauta A, Palumbo A, Castiglia SF, Mollica R, Santilli V, et al. The Barthel Index: Italian translation, adaptation and validation. Int J Neurol Neurother. 2015;2:2–7.

Prodinger B, O'Connor RJ, Stucki G, Tennant A. Establishing score equivalence of the functional independence measure motor scale and the Barthel Index, utilising the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health and Rasch measurement theory. J Rehabil Med. 2017;49:416–22.

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83.

Garratt AM, Ruta DA, Abdalla MI, Buckingham JK, Russell IT. The SF36 health survey questionnaire: an outcome measure suitable for routine use within the NHS? BMJ. 1993;306:1440–4.

Apolone G, Mosconi P. The Italian SF-36 Health Survey: translation, validation and norming. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1025–36.

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71.

Sica C, Ghisi M. The Italian versions of the Beck Anxiety Inventory and the Beck Depression Inventory-II: psychometric properties and discriminant power. In Lange MA, editor. Leading-edge psychological tests and testing research. Nova Science Publishers; 2007. p 27–50.

van Leeuwen CM, Kraaijeveld S, Lindeman E, Post MW. Associations between psychological factors and quality of life ratings in persons with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Spinal Cord. 2012;50:174–87.

Chen HM, Shih CJ, Lee CF, Hsu SY, Huang YH, Lee TH, et al. The use of Short Form 36 and Beck Depression Inventory in acute cervical spinal cord injury patients. Neuropsychiatry. 2018;4:1278–89.

Snell WE. The Multidimensional Sexual Self-Concept Questionnaire. In: Davis CM, Yarber WL, R Bauseman, G Schreer, SL Davis, editors. Handbook of sexuality-related measures. Newbury Park: Sage; 1998. p. 521–4.

Snell WE, Fisher TD, Walters AS. The multidimensional sexuality questionnaire: an objective self-report measure of psychological tendencies associated with human sexuality. Ann Sex Res. 1993;6:27–55.

Kim HY. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor Dent Endod. 2013;38:52–54.

Dormann CF, Elith J, Bacher S, Buchmann C, Carl G, Carré G, et al. Collinearity: a review of methods to deal with it and a simulation study evaluating their performance. Ecography. 2013;36:27–46.

IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2020.

Crewe N, Athelstan G, Krumberger J. Spinal cord injury: a comparison of preinjury and postinjury marriages. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1979;60:252–6.

Kreuter M, Sullivan M, Siösteen A. Sexual adjustment after spinal cord injury-comparison of partner experiences in pre- and postinjury relationships. Paraplegia. 1994;32:759–70.

Kreuter M, Sullivan M, Siösteen A. Sexual adjustment after spinal cord injury (SCI) focusing on partner experiences. Paraplegia. 1994;32:225–35.

Hartshorn C, D'Castro E, Adams J. 'SI-SRH'—a new model to manage sexual health following a spinal cord injury: our experience. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22:3541–8.

Hess MJ, Hough S. Impact of spinal cord injury on sexuality: broad-based clinical practice intervention and practical application. J Spinal Cord Med. 2012;35:211–8.

New PW, Seddom M, Redpath C, Currie KF, Warren N. Recommendations for spinal rehabilitation professionals regarding sexual education needs and preferences of people with spinal cord dysfunction: a mixed-methods study. Spinal Cord. 2016;12:1203–9.

Anderson KD. Targeting recovery: priorities of the spinal cord injured population. J Neurotrauma. 2004;10:1371–1283.

Sakellariou D. If not the disability, then what? Barriers to reclaiming sexuality following spinal cord injury. Sex Disabil. 2006;24:101–11.

Rotter JB. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychol Monogr Gen Appl. 1966;80:1–28.

Folkman S, Lazarus RS. The relationship between coping and emotion: implications for theory and research. Soc Sci Med. 1988;26:309–17.

van Diemen T, Scholten EW, van Nes IJ, Geertzen JH, Post MW, SELF-SCI Group. Self-management and self-efficacy in patients with acute spinal cord injuries: protocol for a longitudinal cohort study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2018;7:e68.

Frank RG, Elliott TR. Life stress and psychologic adjustment following spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1987;68:344–7.

Chevalier Z, Kennedy P, Sherlock O. Spinal cord injury, coping and psychological adjustment: a literature review. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:778–82.

Wegener ST, Adams LL, Rohe D. Promoting optimal functioning in spinal cord injury: the role of rehabilitation psychology. Handb Clin Neurol. 2012;109:297–314.

Alexander MS, Aisen CM, Alexander SM, Aisen ML. Sexual concerns after spinal cord injury: an update on management. NeuroRehabilitation. 2017;41:343–57.

Lombardi G, Del Popolo G, Macchiarella A, Mencarini M, Celso M. Sexual rehabilitation in women with spinal cord injury: a critical review of the literature. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:842–9.

Kathnelson JD, Kurtz Landy CM, Ditor DS, Tamim H, Gage WH. Supporting sexual adjustment from the perspective of men living with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2020;58:1176–82.

Giurleo C, McIntyre A, Kras-Dupuis A, Wolfe DL. Addressing the elephant in the room: integrating sexual health practice in spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2020:1–8.

Lo Piccolo J, Lo Piccolo L. Direct treatment of sexual dysfunction. In: Handbook of sex therapy. Boston, MA: Springer; 1978. p. 1–17.

Shuler M. Sexual counseling for the spinal cord injured: a review of five programs. J Sex Marital Ther. 1982;8:241–52.

Gilbert E, Ussher JM, Hawkins Y. Accounts of disruptions to sexuality following cancer: the perspective of informal carers who are partners of a person with cancer. Health. 2009;13:523–41.

Eglseder K, Demchick B. Sexuality and spinal cord injury: the lived experiences of intimate partners. OTJR Occup Particip Health. 2017;3:125–31.

Cobo Cuenca AI, Sampietro-Crespo A, Virseda-Chamorro M, Martín-Espinosa N. Psychological impact and sexual dysfunction in men with and without spinal cord injury. J Sex Med. 2015;12:436–44.

Shamloul R, Ghanem H. Erectile dysfunction. Lancet. 2013;381:153–65.

Gill KM, Hough S. Sexuality training, education and therapy in the healthcare environment: taboo, avoidance, discomfort or ignorance? Sex Diasabil. 2007;25:73–6.

Bodner D. What you know and what you should know: sex and spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34:349.

Esmail S, Esmail Y, Munro B. Sexuality and disability: the role of health care professionals in providing options and alternatives for couples. Sexuality Disabil. 2001;19:4.

Kreuter M, Sullivan M, Siösteen A. Sexual adjustment and quality of relationship in spinal paraplegia: a controlled study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:541–8.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Dr. Francesco Rizzardo (CEO of the High Specialization Rehabilitation Hospital of Motta di Livenza, Treviso, Italy) who has always believed in this project, encouraging and helping us to carry it forward. Special thanks to all the participants in this project, with a special mention to H81 Insieme Vicenza ONLUS, for having shared their inspiring experiences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EZ, SS and HACB conceived the idea. EZ and SS collected the datasets. E.N.A. run the statistical analyses. EZ, SS and CFDL wrote the initial drafts and final revisions of the manuscript. ENA, RRR, PP, SM and HACB made substantial contributions in the content of the revised versions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zanin, E., Salizzato, S., Aiello, E.N. et al. The contribution of bio-psycho-social dimensions on sexual satisfaction in people with spinal cord injury and their partners: an explorative study. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 8, 42 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-022-00507-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-022-00507-9